15 minute read

COVER STORY

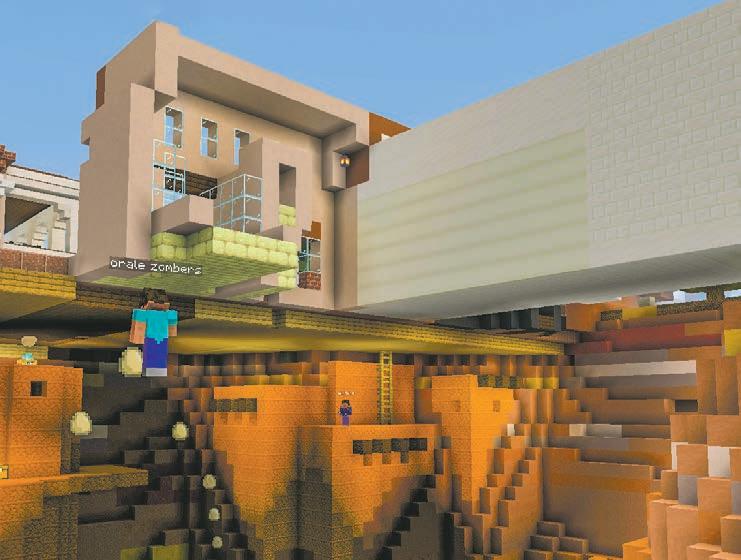

The Plaza Bandstand (where bands stand) New water feature, built by users

Former obelisk; currently DJ booth and dance floor

Advertisement

A bird’s eye view of the Minecraft version of Santa Fe’s Plaza. Natay and Tenorio built surrounding areas as well, including a pueblo-like structure beneath the city streets.

Santa Fe artists/activists Ehren Kee Natay and Dylan Tenorio want to gather post-obelisk data through Minecraft

ALEX DE VORE alex@sfreporter.com

In late 2019, after years lying dormant, SFR attempted to relaunch our legendary 3-Minute Film Fest. It seemed a promising affair, too, with dozens more submissions from local filmmakers than we ever thought possible, plus judges like filmmaker and Three Sisters Collective co-founder Autumn Billie (Diné) and Emmy-winning documentarian Kaela Waldstein of Mountain Mover Media.

Then, as we’re all so sick of reading, the pandemic happened, forcing us to delay the fest through all of 2020 and most of 2021. The filmmakers were, how to put this—kind of bummed. But in the end, we managed to cobble together an in-person event at the Center for Contemporary Arts mere days before the new year where, to a sold out house, we presented nearly 90 minutes of funny, strange, clever or otherwise all-too-real films clocking in at three minutes or under.

We were also proud to crown a film dubbed Minecraft Santa Fe as the winner.

The movie from Ehren Kee Natay and Dylan Tenorio (both Kewa Pueblo and Diné) was produced through local nonprofit Littleglobe for its Littleglobe TV series and takes place entirely within the video game Minecraft, a pixelated and adorable building sim wherein anyone with enough patience can create any type of world they wish. Across the globe, users have built everything from Studio Ghibli’s iconic worlds and The Simpsons’ Springfield to the Titanic, Notre Dame and—well, if you can think of something, it probably exists in Minecraft. Natay and Tenorio set their sights admittedly a little smaller, creating a version of the Santa Fe Plaza and its surrounding areas, replete with the Palace Avenue clock, Frito pies at the Five & Dime, the bandstand shelter and, as a bit of an easter egg, a pueblo-like structure hidden beneath what would be Water Street. They also included the obelisk.

Now, every Santa Fean knows activists tore the monument down on Oct. 20, 2020, Indigenous Peoples Day, née Columbus Day in Santa Fe (and other more forward-thinking communities around the country), but the purpose of including the once-erect stone slabs in their film is part of a more intensive would-be project from Natay and Tenorio through which they hope to engage local youths and/or classrooms in discussions about the future of our fair city.

The film includes numerous young gamers excitedly rushing their avatars around the Plaza to identify the spaces and places they know. When they eventually come to the obelisk, they discuss its demise and plan together: First they transform the thing into a water fountain. Then,

Dylan Tenorio (left) and Ehren Kee Natay during a recent in-game photoshoot via Minecraft.

ALEX DE VORE

Wherein real life imitates art.

deciding dance a bit more universal, they tear it down and, through open dialogue, choose to rebuild the site as a dance floor for breakers. And then they dance.

As the city’s CHART process for public engagement surrounding the meaning of monuments—like the one with the racist inscription that had stood on the Plaza since shortly after the Civil War— continues, the up-and-coming filmmakers are setting out to collect data of their own through their Minecraft vision of Santa Fe. It’s not only a better means to engage with youths, who comprise a major chunk of the game’s concurrent 141 million users, it’s surely more fun than filling out questionnaires and attending Zoom meetings .

The process to address the Plaza will likely be a long one. Still, with Valerie Martinez of nonprofit Artful Life, on contract with the city to run CHART, telling SFR the organization is willing and able to adapt to any community input, including future data gathered through Minecraft, Natay and Tenorio might have created one of the most significantly welcoming ways for Santa Fe’s younger citizens to have a voice. It just needs to be adopted in the classroom.

SFR: What is your main impetus in creating, cultivating and running this slice of Santa Fe in Minecraft?

Ehren Kee Natay: It was first a way for us to have some socialization during the pandemic. I remember us kind of joking like, ‘It would be so cool to be paid to do stuff in Minecraft,’ and were joking we should do it for an episode of Littleglobe TV. We were laughing about it, but I started thinking about it seriously—what if we did something that was based off somewhere in Santa Fe? I thought, we can make something that looks like a pueblo structure; we can have red earth, cactuses; kind of make it like a desert scene. We started talking about other places in Santa Fe that are recognizable, and the one place everybody knows is the Plaza. Dylan Tenorio: I think it was being able to just play with a friend and make something you both kind of knew. When you’re building something together, it’s just like playing with Legos, but you’re also using your memory to think about what things are really like. I think the creative impetus came from that. It was something like, we just really wanted to keep playing together. It was ‘let’s

CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE

make this thing people can recognize and they can see just like we can.’

Was this before the obelisk was torn down?

EKN: I believe it was definitely already torn down. The obelisk had come down, but it was before CHART.

DT: The youth episode of Littleglobe TV was in June, and we were working on this heavily in early June or late May.

Did the idea come together all at once, or did it take time to formulate?

EKN: It was like an aha moment. Dylan would work on it, and I would come in at different times when he wasn’t on. It was really fun to just show up and see, there’s the Palace of the Governors or Dylan adding some trees or structures; railings or stop signs. We’d continually add things, so the whole time we’re thinking we had to show this to somebody. We’re thinking we had to bring some kids in here and show them what we could do. We were studying the possibilities as we created the world. DT: I think the sentiment was already there, the idea was the question of who could decide, who does decide [what goes on the Plaza], would be the youth, or should be. Our idea that sprouted from that was that we were really just doing this thing that doesn’t affect us right now, but the youths are the ones who’ll have to live with it.

Did you create the world from memory, or was it researched? It seems kind of dream-like.

EKN: We used Google maps, and there was one time when I drove around the Plaza to really get a feel for it. But that whole time we were building, it wasn’t until it was like 85 or 90% done that I went to see the Plaza. It was kind of surreal to see this place I had mapped out.

ROBOTSMOSTLY

ROBOTSMOSTLY Natay (right) and Tenorio throwing an impromptu dance party on the spot where the virtual obelisk once stood.

Santa Fe as we know it is built atop stolen land, and in Natay and Tenorio’s Minecraft version, the notion becomes literal. DT: I would think of it as something of a liminal space or a transitionary zone. This isn’t the real Plaza, but it’s something that could lead us to a Plaza we can all agree with. This is a great space, and it’s a space that will have to transition before we can get it to be where we want it in real life. In Minecraft, you see all these blocky forms, like the sun in the sky—it’s not exactly real, it feels like it’s been constructed, there’s artificial lighting.

Was the goal to always engage youth on their turf, as it were? How did you find young people to play?

EKN: It was funny because [my friend] Colin [White] introduced me to Minecraft, and Colin was a breakdancer at Warehouse 21, where the main breakdancing teacher, Ricky Rodriguez...his two boys would play Minecraft, and Colin would be watching them, and it was something we could all do together. Luke and Ricky Jr. would play with us, so we already had this experience where it’s totally different playing with kids— where their imagination goes. We wanted to have that youthful interaction when we were making the film, so we put out a call on Facebook to see if anybody else would want to join, and we got one person from the Navajo Nation who has a son who plays Minecraft. Plus Luke and Ricky. DT: It’s a definite different experience playing Minecraft with children. They really go. For me to play as an adult, I think of structures and how I can efficiently build things. There’s a system to it, but when a kid goes in, it’s anything goes. So, when I heard about Ehren and the kids playing, we thought we could really see if they could figure out what they want to see in the middle of some place they recognize, like the Plaza. So CHART’s trying to figure out what’s happening and we just were like, ‘This could be another way, and people could definitely go to this virtual place and show us what they would like to see.’

SPECIALIZING IN:

NOW OFFERING

APR PERFORMANCE PRODUCTS S. MEADOWS RD. AIRPORT RD. 3909

ACADEMY

RD.

CERRILLOS RD.

Checking In With CHART

The City of Santa Fe officially approved the CHART process— otherwise known as Culture, History, Art, Reconciliation and Truth— in January last year to identify and address community concerns surrounding the felled obelisk, as well as the future of public art and/or monuments on the Plaza. By July, it hired Albuquerquebased nonprofit Artful Life as the project facilitator.

Led by Santa Fe-born Valerie Martinez, formerly of local nonprofit Littleglobe, Artful Life immediately set about forming a team of paid facilitators and interns, all of whom are Santa Fe residents, and creating an outreach and engagement model that late last week, held its first-ever Zoom dialogue session to address one of a number of upcoming topics: monuments.

Martinez tells SFR that prior to the session, public outreach and online surveys pulled in the rough equivalent “of a 300-page book, single-spaced, in terms of data.” That information will continue to inform the topics for the dialogue sessions, which will run monthly for the time being. Each topic will be announced ahead of time to allow potential participants time to register for the session and prepare. And while Martinez says she understands “monuments” is a nebulous term, she is also quick to point out that her organization has not and will not be making any decisions about the talking points, the future of the Plaza or otherwise. The topics, she notes, are dictated by CHART participants, and Artful Life’s position in the process exists solely to gather information from and for the community.

“The survey launched last September, we had four months, and since online surveys tend to skew a little older, we made a particular effort to get to younger audiences,” Martinez says. “Anybody can register [for the survey and dialogue sessions], and we take that information and book people for particular times. They tell us their preferences and we can accommodate their needs—they can also request sessions in Spanish or that are bilingual.”

Martinez says it’s a little too early to have identified any particular patterns in the data Artful Life has gathered for CHART, but that 86 Santa Fe residents attended the first dialogue session. That may not sound like many, but it resulted in a goldmine all on its own. And there’s more to come.

“What I’d say,” she continues, “is that the first months will be creating that administrative structure and foundation, and then we launch a wide array of public events. These dialogue sessions are just one type, so we’ll also be hosting other kinds of community conversations. There will be lots of ways for people to participate.”

For now, she says, the best way to add your voice to the mix is to engage through chartsantafe.com. There, interested parties can also learn more about the 18-person team working on the process and sign up for dialogue sessions and surveys. The goal is for the process to adapt and evolve over time based on community needs. CHART facilitators, for example, are willing to talk with anyone interested in voicing an opinion, be they a single person, a DIY organization or what-have-you.

“The great thing is that anybody can contact us any time with information, and I think we’ve said this from the beginning, that the process is thoroughly planned and depends entirely on the input we’re getting,” Martinez explains. “But it’s also iterative, so we learn and adapt as we go. We need to learn along the way. For example, one thing we’re looking at is one of the hardest populations to reach, ages 20 to 29, who are maybe not at colleges, they’re working in service jobs; we’re doing our best in the midst of a pandemic for more in-person outreach, and we’re looking to demographics of the county to help us understand where we need to reach out in more creative ways.”

Valerie Martinez of Artful Life.

Have more users signed up?

DT: So far, that initiative hasn’t been completely sent out. We have, as Littleglobe, introduced this idea to a lot of local teachers who did like the idea, but there was no initiative after that point. We’ve gotten some teachers who like the idea of students expressing what home means to them through Minecraft; what structures they could build that they relate to what they call home. EKN: We would be up to having this in classrooms, but it’s been hard for us to make this connection. One thing we hope that comes out of getting some publicity is someone speaks up. There’s a lot we could do here if we step up.

Let’s say a bunch people read this story and want to engage with your Minecraft world. Would you want to share your findings with CHART and the city?

DT: I’d say the original notion of this was for a youth episode for Littleglobe TV, and this was definitely made for people to see what the youths are doing in Santa Fe. But we realized this could definitely be a lot bigger than that, and I think we are i nterested in helping the city have more input from the people who will actually inherit these spaces. EKN: I think so. We should start thinking about things all-inclusively, including children and elders. People who don’t have access to getting their voice out there in ways that really touch others—through art, music, through games, even. Especially with the pandemic, we learned that we can meet whoever we want if we set up a Zoom call, do a video Facebook; we can meet these people—if they’re on the internet we can make it happen. We can connect to people going through the same things. We can go across the world. What might they have to say about similar things? That could be valuable.

What’s your endgame here, if there is one?

EKN: Dylan and I have been talking about doing the next phase of this as part of Midtown. We want to keep the idea going, so we’ve talked about recreating…what would be the easiest place in Midtown to create? It’s a section that will impact the people of Santa Fe in a far greater way than the obelisk has. I’d like knowing there might be more opportunities for support, financially and with participation and engagement with the community, and from Littleglobe, which funded the original project. DT: I think it’s definitely a growing thing. I don’t think we know all the answers yet, because it’s a lot of considering resources and accessibility for people to get on this kind of platform and the actual input about who can express themselves through Minecraft. I think people who are used to video games can get it, but those who aren’t, might not. It’s a bigger conversation that would be great to have, and maybe this is not the only way we can express these types of ideas. Maybe there are other avenues for getting voices out there, this is just one of them.

So what happens next?

DT: Probably the idea of Midtown, or something that would be in the next Littleglobe TV episode. What part of Midtown would we want to build? There are different ideas going around, though we work with a relatively big team and it gets bigger during a production, so there are 20 people working and Ehren and I are just two of the 20. One idea I had was to perhaps have alums from the College of Santa Fe and Santa Fe University of Art & Design talk about their memories while they walk around the campus— in Minecraft—just to voice what kind of lives were lived there, what kind of place that was that is no longer there; to un-familiarize the familiar. EKN: I would really like to see some interest [in Minecraft Santa Fe] or somebody who can help us into interacting with classrooms. Like I said, we put out a call to see if kids would log in and play, and we got three kids, two of which were because I knew their parents. I’d like to see about help to get us some funding into the project, or some kind of programming set up through the schools through which we can start having these conversations. I think it’s awesome to bring in students. Who are the other people we’re not thinking about, though? Maybe the homeless people who’re living [on the Midtown Campus] during COVID. There’s so much history there.