25 minute read

COVER STORY

Santa Fe Unidos

In just its third year, New Mexico United has developed a loyal, low-profile soccer following in the capital

Advertisement

BY WILLIAM MELHADO william@sfreporter.com

Damian Reyes, a United player, is noticeably shorter than the defenders he faces. What he lacks in size, he makes up for in confident speed. Receiving a good look from the open left field, he fakes one defender, then another and chips the ball beyond the keeper’s splayed hands for the team’s first goal.

Reyes leaps gracefully in celebration against the shadows that stretch across the pitch at the Santa Fe Municipal Recreation Sports Complex one Wednesday afternoon.

“Alright, go drink water,” coach Daniel Trejo tells his team. Most of the players trot to the sideline, where their parents sit on blankets with toddlers—the players’ younger siblings.

But Reyes, 10, keeps kicking the ball with his co-captain, Derek. Reyes never misses a day of practice; he’s clear on what lies ahead for his future soccer career.

Without hesitation, Reyes tells SFR he’ll play for the other United team when he gets older.

His favorite player on the United Soccer League team based in Albuquerque is Sergio Rivas. The midfielder, with 21 shots on goal this season, four of them finding the mark, was born in Mexico but grew up in New Mexico.

Reyes’ dreams of making it to the professional level like Rivas got a boost from Santa Fe United Football Club (despite the shared name, there’s no affiliation between the two soccer teams). The youth team helps get kids onto the pitch who otherwise might not have a chance to participate in prohibitively expensive tournaments—a longstanding, well-known barrier to soccer that’s been a hallmark of private clubs in Santa Fe and statewide.

Reyes, his family and scores of other Santa Fe-based United supporters reveal that in the capital, there’s a wellspring of pride and devotion to New Mexico’s first professional soccer team.

Talking to any New Mexico United supporter, whether it’s in the parking lot before a game or on fields south of Santa Fe, passion for the three-year old team is evident. Some say it’s the universal love for soccer, often referred to as the world’s game. Others point to United’s bold-colored, progressive, artsy merchandising schemes.

Whatever the source, the popularity of New Mexico’s first truly successful professional sports team is impossible to ignore.

The jubilance in the team’s host city is obvious in bars or at tailgates, but this obsession has taken root outside New Mexico’s primary population center, too.

Amongst the art galleries, breweries and boutique shops, a small and mighty contingent of United supporters has emerged in Santa Fe. What this loose collection of fans lacks in organized structure, it makes up for in unassuming enthusiasm.

New Mexico United played its first game

against the Fresno Football Club in March 2019. In the brief time since, supporter clubs have sprouted around the state. The largest and most vocal, the Curse, is based in Albuquerque. The group’s name comes from territorial governor Lew Wallace’s dispirited assessment of the state: “All calculations based on our experiences elsewhere fail in New Mexico.”

And for fans up in Santa Fe, there are the 7K Ultras, a rag-tag crew that lacks “card carrying” members. After extensive snooping around social media, watch parties and an in-person match, SFR confirms the group doesn’t maintain fixed leadership or a religious following.

Rather, United fans in the capital city who spoke with SFR prefer to exercise their soccer enthusiasm through a variety of activities and groups. Yet everyone who claimed the badge of “supporter” clearly lives daily with the spirit of “Somos Unidos.”

That was the goal for Peter Trevisani, who was acutely aware of New Mexico’s less than impressive record with professional sports. But the Santa Fe resident and owner of New Mexico United says getting the state into the pros wasn’t his primary motivation for starting the team.

-Peter Trevisani, NM United owner

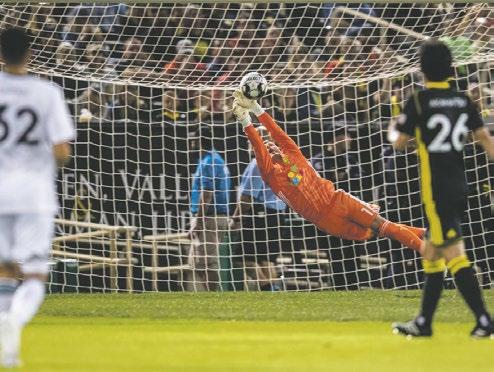

United’s goalkeeper Alex Tambakis jumps for a save. Tambakis joined United in March after playing with North Carolina FC.

“It was never about soccer, it was just about bringing the community together and that was always important to me. So that’s what we led with; we let people know it’s for everybody,” Trevisani tells SFR outside the stadium, where his team is about to do battle with Salt Lake City’s Real Monarchs.

The tailgate is in full swing, and Trevisani is interrupted by a young fan with a popsicle-stained mouth and tongue.

“Can you tell Daniel Bruce my birthday is on May 29th, ‘cause his is on May 13th,” the boy demands.

Trevisani promises to share the information with Bruce, United’s 25-year-old midfielder from England. The kid hustles back to his pickup game in a makeshift pitch set up on the grass across Avenida Cesar Chavez from Isotopes Park.

Grills hiss and bright yellow, black and rainbow flags blur individual tailgates together into one massive early evening party.

“It’s for everybody. It doesn’t matter who you are, what language you speak,” Trevisani says, sweeping aside any notion that there’s a difference between United fans from Santa Fe, Albuquerque or any other supporter pockets around the state. “Here, we just get to say we’re all United, we’re all part of the same thing. As long as you come with your most authentic self, it’s for you. I think it’s that collective belief.”

United supporters and Trevisani hope to translate that unified passion into collective action this November by building a stadium for the team. The proposed publicly-owned stadium has a $50 million price tag, financed by a tax revenue bond measure, which Albuquerque voters will decide on come Nov. 2.

Social media buzzes with opponents and supporters arguing about the stadium idea. Some critics say the money would be better spent on more cops and other crime-fighting strategies in a city with spiking rates of violence, while advocates of the stadium point to the team’s immense popularity— the fresh arena would provide a morale boost to a struggling Albuquerque.

United has certainly cultivated a following: The merchandise is ubiquitous in Albuquerque and beyond, and the team draws a crowd every time it turns out to play.

David Carl, a spokesman for United, says the team has led the league in attendance. USL Championship, a Division II professional soccer league, hosts 31 teams across the country. In 2019, an average of 12,693 fans attended each United game, almost 2,000 more supporters than the team with the second highest season average.

This year, with pandemic restrictions still in place in some parts of the country

and some fans still nervous to join large crowds, only the Louisville City FC in Kentucky has a higher attendance average than United.

For Trevisani, all those ticket sales allow for more than just a healthy bottom line. He points to the Somos Unidos Foundation, which launched during the pandemic last year and runs programs to support schools, artists and athletes around the state. Through funding from the foundation, United started a free soccer academy for youth players in the state—it’s one of only three academies in the country where every player receives a full scholarship, says Carl.

Klaus Voigtlander moved to New Mexico

over two decades ago from Germany, where he watched football—he clarifies, “American football,” which Voigtlander finds too aggressive—because there wasn’t a local soccer team that won his heart.

But United’s formation gave Voigtlander a taste of something he’d missed.”I feel like I’m back home, somewhere in Europe,” he tells SFR moments after Amando Moreno scores United’s first goal against Real SLC during a recent match. Voigtlander sports a Meow Wolf-emblazoned jersey and a yellow flag for a cape.

When he heard about where United would play, Voigtlander was skeptical: “In The Lab? In a [triple-A] baseball stadium?” The team’s quick rise to popularity also came as a surprise to the German national. “Americans want to watch American football and baseball and basketball, but not soccer,” he says. “I thought I was by myself.”

He wasn’t.

Enjoying a pretzel and a beer, Voigtlander, a long-time Santa Fe resident, speaks of the slow but consistent growth of interest in soccer over recent years, noting the US women’s team that has dominated the world stage.

Voigtlander contends soccer in New Mexico will continue to expand and, hopefully, he says, draw families away from the violent, concussion-inducing sport of American football.

Voigtlander bemoans the commercialization of European soccer teams, which has led to, among other things, soaring ticket prices. He can watch United for $25; back home, attending a match would run almost $150—for that price he could attend six United games.

He contrasts the elitist vibe of European soccer against United’s accessibility.

Voigtlander says he would like to see United at the top level of professional soccer in the US, Major League Soccer, but the team’s current status has its benefits. “This is beautiful, for us, for our community,” he says looking out over the crowd of families and friends.

WILLIAM MELHADO

Peter Trevisani and a group of youth soccer players at the supporters’ tailgate ahead of United’s match against Salt Lake City’s Real Monarchs.

Tom Ludzia didn’t anticipate becoming

a United fan.

His preferred sport, ice hockey, isn’t popular in the sunny state of New Mexico, and he didn’t follow soccer before his first game. He didn’t even expect to attend after waking up at 4:30 am one day to start brewing beer at Second Street Brewery. But his friends cajoled him into joining them for a game after his long shift.

It only took one, says Ludzia, dressed in work overalls and sipping on his brewery’s award-winning Oktoberfest on a Thursday afternoon.

“The last time I felt that type of energy was 1994, in Madison Square Garden when the Rangers won the Stanley Cup,” Ludzia tells SFR, burnishing his hockey-fan cred by evoking an event that’s near religious for many New Yorkers. “The excitement, I hadn’t felt that in ages. After that we were committed, so we got tickets on the way home for the next match.”

Ludzia has the same relaxed attitude the next time SFR runs into him at the tailgate, where he’s helped lubricate a group of United supporters with 10 gallons of Second Street beer. Since that first season, Ludzia has become tightly entwined in the United supporters network, serving these days as co-chair of community outreach for the Curse.

The supporters club maintains no official connection with United, but their good work is in honor of the team’s name. Ludzia leveraged his roles with the Curse and Second Street to help low-income families in Albuquerque with basic laundry services. They’ve organized with the nonprofit Laundry Project, to raise money through the sale of Beyond the Pitch, a limited-release session India pale ale from Second Street that embodies the supporters’ spirit.

Ludzia says he took on the community outreach role to help spread the good work of the Curse beyond Albuquerque. The group has donated to Santa Fe Public Schools’ Adelante Program, which helps unhoused youth, and the food bank Casa de Peregrinos in Las Cruces.

In its first two years, United made deep playoff runs, meaning even more fall evenings for fans from around the state to holler in The Lab. Ludzia’s mild concern about this year’s prospects appear prophetic: New Mexico’s team record this year isn’t as impressive as years past.

With eight games still to play—including one tonight against Rio Grande Valley FC—

Where the

Southwest

meets the Scottish Highlands

Aztec, New Mexico October 2 & 3, 2021

and a 8-8-7 record, it isn’t likely to play past the regular season.

No one SFR spoke with seems to care.

When SFR catches up with Ashley Young

and her family in section 120, row B, they’ve been in their seats for almost an hour already and the whistle marking United’s face off against the Utah team hasn’t blown.

The self-labeled “super fans” have season tickets in seats adjacent to the Curse’s area (section 118). “I couldn’t sit in the supporter’s section because I would have too much worry about not knowing where my seat was,” Young says.

The legendary rowdiness in Sections 116 and 118—on full display again during SFR’s visit to the pitch—can be immensely fun, if a little distracting from the game, Young tells SFR.

Her daughter, Callan Cox, a junior on the Santa Fe High School soccer team, also prefers the “supporter-adjacent” section because she wants an unobstructed view of the match. Right of the north goal and only a few feet from the corner flag, their second row seats offer just that.

Before the game starts, with one of the best vantages in the stadium, Young tells SFR: “If there’s corner kicks, we’ll be on TV.”

When she’s not managing the electronic health records system for La Familia Medical Center, Young pours her energy into supporting Santa Fe High’s soccer team. As a team parent, Young has worked to make the school group accessible and memorable for each athlete.

2021 Season 2020 Season

Games Win Loss Tie Goals

24 9 8 7 30

15 8 4 3 23

2019 Season 34

Sergio Rivas

POSITION: MIDFIELDER SEASON APPEARANCES: 21 GOALS: 4 SHOTS: 23 ASSITSTS: 2

Born in Chihuahua, Mexico, Rivas played for Seattle University after growing up in Albuquerque and attending Cibola High School. After graduating, Rivas signed with the MLS San Jose Earthquakes in 2019. Rivas started with United at the beginning of the 2021 season, marking a return to his home community. Hailing from Warrington, England, Bruce signed with New Mexico United after playing for University of North Carolina at Charlotte. He has a total of four career goals with United. This is the 25-year old’s third season with the team. Sandoval is an Albuquerque native and spent the majority of this college career at the University of New Mexico. He played for a number of professional teams, Real Salt Lake, San Francisco Deltas, Atlanta United 2, before signing with New Mexico United in 2019.

11 10

Daniel Bruce

POSITION: MIDFIELDER SEASON APPEARANCES: 22 GOALS: 2 SHOTS: 11 ASSITSTS: 2 13 59

Devon Sandoval

POSITION: FORWARD SEASON APPEARANCES: 24 GOALS: 4 SHOTS: 37 ASSITSTS: 1

Tom Ludzia shows off a six-pack of Beyond the Pitch, a session India pale ale that Second Street Brewery put out with the United supporters club, the Curse, to raise money for the Laundry Project.

Unlike private clubs—those same expensive youth teams that led to the formation of the Santa Fe United—Young has helped to make sure soccer is free for anyone who wants to play.

“I really just want them to know that, regardless of which roster they were put on, JV or varsity, that they’re all one team, and that everything we do is for all of them,” Young says.

The Santa Fe High Demons don’t have to pay a dime for the swag or trips, including the upcoming Oct. 9 United game against Rio Grande Valley FC Young has planned as a team field trip of sorts.

For Santa Fe United, the club featuring young Reyes, the team hopes to also take a trip to Albuquerque to watch the state’s pros in action—and with enough practice, maybe audition for the squad one day.

“Our goal is for one day, hopefully, these kids with our help, and the help in the community and their donations, they’ll be able to at least go and try out for New Mexico United,” Omar Reyes, the father of the young Santa Fe player, tells SFR.

Among the reasons they named the Santa Fe team United: community support for the youth club is so strong.

Reyes understands how impactful United’s momentum has been for the state. Since the team’s first season in 2019, the Reyeses have become big fans.

“If you’re from Santa Fe, it’s a passion to be from Santa Fe. If you’re from Albuquerque, it’s a passion to be from Albuquerque,” Reyes tells SFR as throngs of young players clad in yellow and blue jerseys shout and kick soccer balls. “For us to like soccer, that’s our passion, that’s our life. For us that’s like going to church. And if New Mexico United is in Albuquerque, it’s an hour drive, so that’s like going to church for me personally.”

Back in The Lab, the older United players, sporting their black Meow Wolf kit, warm up on the pitch. Supporters who have traveled from all corners of the state have come out to be in community with each other.

She’s referring to the Curse, highlighting the Albuquerque-based group’s inclusivity and eagerness to engage with supporters all over the state.

For Young, there’s a secondary motivation behind hauling the Demons to The Lab: “Obviously by taking them to a United game, I am trying to recruit more” Santa Fe supporters.

Young and Ludzia, the Second Street brewer, both mention that Santa Fe fans have taken part in a number of supporter activities led by the Curse, like painting banners for each of the United players and greeting the team at the airport when they return from away games.

Ludzia agrees with Reyes—he hasn’t seen much distinction yet between fans in the two cities.

“As far as the passion for the club, we got a longer drive, that’s the difference,” Ludzia says, back at the brewery off Second Street in advance of an upcoming home game that weekend. “And yet, depending on the day, you know how Albuquerque is: To get to the other side of Albuquerque it might take them just as long as it takes us to get home with no traffic.”

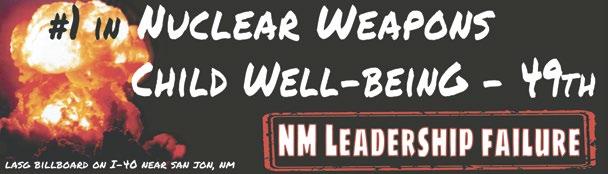

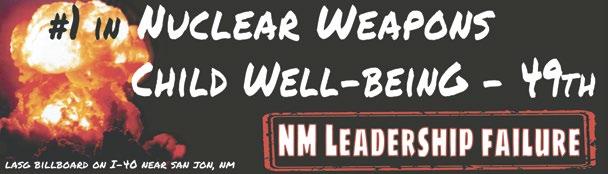

Huge expansion of nuclear weapons mission underway despite climate collapse, crying social and economi

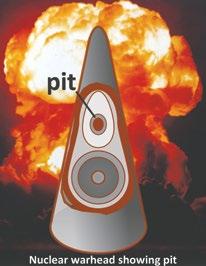

Twenty-two miles from the Santa Fe Plaza, the Na�onal Nuclear Security Administra�on (NNSA) has a crash program to build a plutonium processing center and nuclear weapons factory at Los Alamos Na�onal Laboratory (LANL). It’s purpose is to make plutonium warhead cores (“pits”) for a new kind of warhead for a new $100 billion intercon�nental ballis�c missile (ICBM). To create the Did You Know? new factory LANL is remodeling its 1970s-vintage plutonium facility while also construc�ng new infrastructure on ◾ Los Alamos Na�onal Laboratory (LANL) is building a a large scale. factory for plutonium nuclear weapons cores (‘”pits”). Why a crash program? ◾ It is the costliest project in the history of New Mexico. Why at LANL? ◾ ◾ New pits aren’t needed for any U.S. nuclear weapon. LANL’s old facili�es don’t meet federal safety standards. At its most basic level, the answer lies ◾ A new, safer pit factory is being built in South Carolina. in the obscene profits available from the new nuclear arms race, a perceived ◾ The LANL factory would have huge regional impacts. need to grow the U.S. nuclear weapons complex to offset declining U.S. global power, and the constant efforts by New Mexico poli�cians to increase nuclear pork-barrel spending in the state – while neglec�ng the state’s real priori�es. Since 1989 LANL has failed four �mes in its a�empts to build a pit factory. In 2019, the Ins�tute for Defense Analyses warned NNSA that crash efforts are likely to fail. Even if LANL succeeds, without accidents, the program provides no addi�onal “nuclear deterrent” value.

LANL pit production has nothing to do with maintaining existing U.S. weapons

Every U.S. nuclear warhead and bomb contains a pit. These slowly age. If for some reason the U.S. is s�ll building nuclear warheads in the late 2030s and 2040s – which we can be sure will be an era of deepening climate collapse, global famine, and other severe crises threatening the very existence of the U.S. – they might need new pits. At the earliest. Un�l then, at least 15-25 years from now (or even longer if the U.S. stockpile shrinks), no new pits are needed. Right now, the U.S. has a gigan�c arsenal of 2,000 deployed warheads with 1,800 in reserve and 1,750 re�red warheads, plus about 5,600 aging but useable spare pits, depending on type.

LANL facilities: old, unsafe, unreliable The LANL pit factory and related expansion is the costliest project in New Mexico history

Construc�on and startup costs for the factory lie in the $11 billion range, far above ini�al es�mates. Opera�ng costs will run about $1 billion each year. LANL pits will cost an absurd $50 million each − minimum. Preparing this factory is the most expensive construc�on project in the history of New Mexico, rivalling construc�on of all the state’s interstate highways put together. This gigan�c undertaking already employs more than 2,000 people full-�me, plus hundreds of subcontract workers. When and if it starts, pit produc�on would be a 24/7 endeavor, because the LANL facili�es are so crowded. LANL wants to hire another 2,000 pit produc�on workers for round-the-clock opera�ons. Many safety issues remain unresolved. Also, shipping the large quan��es of nuclear waste produced during produc�on will take precedence over the removal of LANL’s extensive Cold War wastes. As a result, cleanup may never happen.

By the �me pits are actually “needed,” LANL’s facili�es will have “aged out.” A commitment to LANL pit produc�on therefore means a commitment to another factory, beyond the one being built.

Meanwhile LANL’s produc�on capacity is too small to support more than a frac�on of today’s arsenal, even if LANL could produce pits reliably for a long �me without building a new factory, which nobody seriously believes is possible.

The U.S. has not had a func�oning pit factory since 1989. There is tremendous poli�cal pressure to build an adequate, reliable factory, beyond LANL’s jerry-rigged, temporary one. To this end NNSA is remodeling a par�ally-built plutonium facility in South Carolina (SC), which is large enough to make as many pits as needed without calling upon LANL for anything more than research, development, and training. The brand-new, safer SC facility will be opera�ng by 2035 at the latest. This is plenty soon enough to make pits – or to not make pits, the wiser choice. The SC facility is also ten �mes as far from surrounding communi�es as LANL’s. Unlike at LANL, the SC facility is not located adjacent to powerful earthquake faults and sacred Indian lands. As NNSA has tes�fied, finishing the SC facility is faster and cheaper than trying to build a proper new plutonium facility at LANL, assuming a loca�on for such a facility could be found – which is doub�ul. Thus, from any but the most ideological and par�san perspec�ves, LANL’s program is wasteful, dangerous, and destruc�ve.

More nuclear weapons jobs will not bene�it the region

performance rela�ve to other states, many people in New Mexico s�ll “look to the labs” for economic salva�on. Besides permanent pollu�on and more than 1,600 federally-documented occupa�onal deaths, what does the region have to show for all the money and talent poured into LANL? Labor markets are distorted as LANL absorbs local talent. Housing markets are likewise bid up. And scarce resources such as water and road capacity are consumed. Taxpayers in LANL bedroom communi�es pay for public services and educa�on for LANL commuters and their families, o�en with net nega�ve fiscal impacts. Over its history LANL has spent $130 billion in northern New Mexico, a vast sum anywhere but especially here. Yet LANL has generated neither shared prosperity nor social development. A few have benefited economically, but most have not. As a result, LANL drives regional inequality, with devasta�ng social, economic, and poli�cal impacts. Perhaps worst of all, poli�cal leaders come to focus and depend on LANL and its wealthy employees – or else fear its power, exerted indirectly through poli�cal par�es and organiza�ons. Imagina�ons are s�fled as narra�ve dominance becomes complete. Poli�cal leaders become unable to “think outside the labs,” an outcome carefully engineered at taxpayer expense by LANL. Green, social goals – the an�thesis of LANL’s core missions – are derailed and deferred. LANL suborns the a�en�on and loyalty of our poli�cal and civic leadership and provides false, self-serving answers to the economic, environmental and social problems we face. Instead of coming together to truly grapple with these problems, our leaders talk about LANL “jobs”, a narra�ve that centers our a�en�on on LANL – not where it belongs, in our communi�es.

Each LANL bomb core would cost $50 million, enough for 1,000 teachers – or thousands of solar installa�ons.

Our state & country desperately need wholesome priorities, not an arms race What can be done, and how you can help

LANL’s semi-secret plans are unclear even to LANL. And they are expanding. Two additional billion-dollar nuclear facili�es are now planned. Once produc�on is underway, a large new plutonium facility will also be needed. According to LANL, 2,000 to 3,000 workers must soon be brought to the site daily in buses because LANL has outgrown local road capaci�es. Meanwhile LANL is nego�a�ng with the Pueblos to build trailer parks for its an�cipated army of construc�on workers. Our Senators, Congresswoman Fernandez, and our Governor all support LANL’s new mission without reserva�on, without even knowing what it entails. So far, these poli�cians oppose transparency and environmental analyses. We have requested their help many �mes. Don’t bother asking − it only encourages their disdain. Given the widespread lack of knowledge we are organizing a public informa�onal and planning mee�ng, to which our congressional delega�on, Governor, and local leaders will be invited. Further ac�on will be necessary, ideally coupled with a rising �de of impa�ence rela�ve to our climate and social emergencies. Manufacturing plutonium nuclear weapons cores takes northern New Mexico in a dark direc�on, foreclosing be�er choices. We need a sustainable, just society that is working to address climate collapse and other crises straight on, not the moral and fiscal black hole of a new Cold War.

How can we build strong, resilient communi�es with priori�es such as these? How can we address the existen�al crisis of climate change? How can we provide a good educa�on for all our children, and support for our elderly? How can we provide real voca�ons, with real meaning, for the rising genera�on? More war, and more prepara�ons for nuclear war, are the opposite of any answer. The scale of these wrong-headed investments corrupts our poli�cians, drains our treasury, and degrades our morality, dragging down our city, our state, our country, and our world – without even considering the rising risk of nuclear war.

Runaway nuclear weapons spending is just part of this year’s $934 billion ($7,738 per household) bill for U.S. “defense” overall, more than half of all congressional appropria�ons. U.S. military spending exceeds the combined total military spending of all the other countries in the world, save three. The U.S. spends more on just nuclear weapons than the en�re defense budgets of all but nine countries. NNSA needs silence and acquiescence in order to con�nue this reckless folly. The last thing LANL and NNSA want is to have to jus�fy their plans in public. Meanwhile LANL hopes to subordinate our educa�onal ins�tu�ons to their needs, so our children can enter their “pipeline” of plutonium workers to be cannon fodder for dreams of world domina�on.

Information & Planning Meeting

Clip & mail to the address at the bo�om.

• Thursday, September 30th, 6:00 – 8:00 pm • Gathering Room, St. John’s United Methodist Church, Santa Fe, 1200 Old Pecos Trail • This is a large hall with superior ven�la�on. Wear a mask.

Yes, I want to help

▯I will be there on September 30th. ▯ I will recruit my friends and contacts to come. ▯I endorse the “Call for Sanity, Not Nuclear Production” (https://lasg.org/wordpress/we-call-for-sanity-no-nuclear-production/) I prefer ▯in person events, ▯on-line events, or ▯neither. I might be able to help with ▯outreach prior to events, ▯other. I would like ▯national email updates (~1x/2 weeks), ▯New Mexico updates & invitations (~1x/week), or ▯neither. I can help financially with ▯a one-time gift, ▯a monthly donation, ▯other, (https://lasg.org/contribute.htm). LASG is a 501 (c)(3) organization. Donations are tax-deductible. Contact me by ▯email_________________________________________________ ▯phone ____________________________________, or ▯wait for now. Address _________________________________________________________City, State, Zip ___________________________________________ Los Alamos Study Group • 2901 Summit Place NE, Albuquerque, NM 87106 • 505-265-1200 • lasg.org • Serving New Mexico for 32 years