13 minute read

COVER STORY

Super Fire

Northern New Mexico’s huge blaze continues to grow while another in the south is heating up fast

Advertisement

BY WILLIAM MELHADO william@sfreporter.com

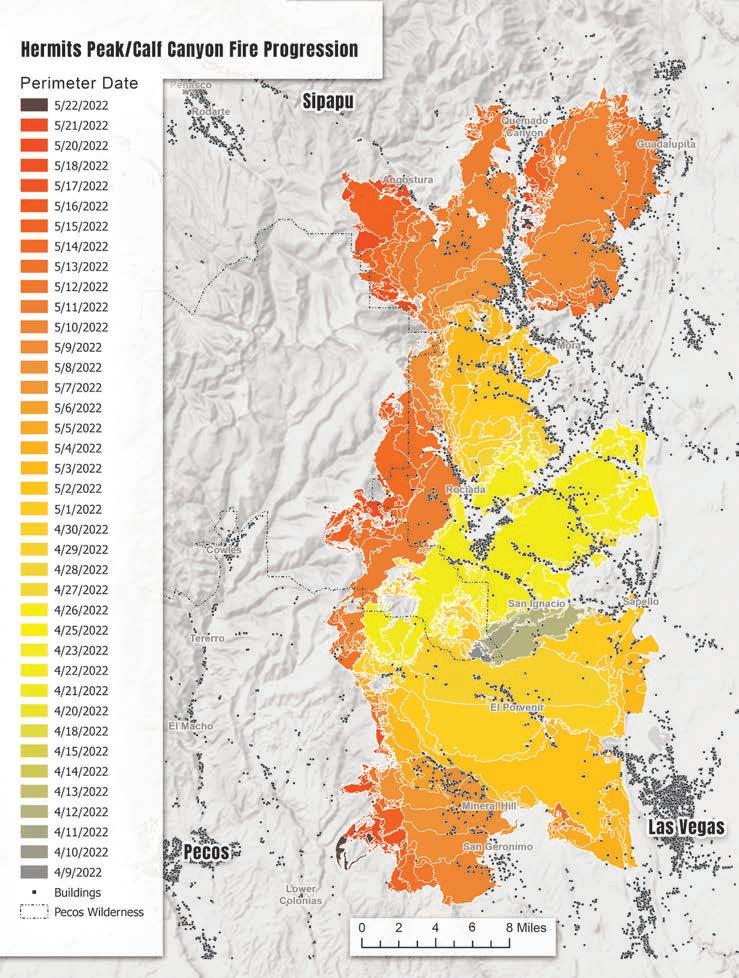

Bulky Super Scoopers and helicopters trailing water buckets have roared seemingly daily over Northern New Mexico during the past month and change, as a historic megafire has consumed 311,148 acres. The fire’s growth has largely stagnated in the past week as crews have slowly increased containment to 41%, as of Tuesday.

The bright yellow, amphibious aircrafts built by the Canadian airplane manufacturer, Bombardier, have become a common sight in New Mexico. At one point during the Hermits Peak/Calf Canyon Fire, every Super Scooper in the country was located at Santa Fe Airport to fight the fire.

But another fire, in Southern New Mexico, is growing with little restraint, forcing officials to pull some Super Scoopers away from the northern blaze.

In just 11 days, the Black Fire has consumed 154,911 acres in the Gila. The human-caused fire became the fourth largest fire in state history. At 11% containment, the Black Fire is all but guaranteed to surpass the 2011 Las Conchas Fire, the third largest, that burned over 156,000 acres.

Conversely, it took the Hermits Peak/ Calf Canyon Fire almost four weeks to reach 189,000 acres.

The Black Fire has burned through largely rugged and remote areas of Sierra, Grant and Catron counties, spurring evacuations. But the region has yet to see significant displacements, like those experienced in Northern New Mexico.

When the Mora County Sheriff’s Office came to his home in Buena Vista, telling him and his neighbors to evacuate, Joseph Weathers didn’t leave.

“They weren’t going to feed my cows. Nobody’s gonna come by and feed them,” Weathers tells SFR, estimating that he distributed over 400 pounds of dog food to his neighbors’ animals.

Weathers stayed behind with his son-inlaw and grandson to protect his home and animals.

With flames only 200 yards from his house, aircrafts and helicopters circled nearby, collecting water from a lake to the south and dropping slurry over the fire.

“I thought I was in the middle of a war zone because all I hear is, you know, these airplanes flying over…my house,” Weathers tells SFR.

The Black Fire continues to challenge firefighters due to its size, rough terrain and limited access. Unfavorable firefighting conditions seen across the state are expected for the Black Fire, including shifting winds and high temperatures.

Increasingly large fires across the state, fueled by drought and climate change, have set the stage for perhaps the worst fire season in New Mexico’s history.

Officials are watching the perimeter of the Hermits Peak/Calf Canyon Fire closely as it moves primarily along its western flank. On Monday, an infrared aircraft flew down the fire’s western edge to detect its boundary and officials found little movement in recent days.

The northerly winds forecast during the week are not expected to push anything out across the lines, said Fire Behavior Analyst Stewart Turner.

“With the moist fuels that we have around the fire I’m not expecting any of those to take or be any problem for the crews to pick up as long as they have their aircraft flying and assist with those,” Turner said during Monday evening’s fire update.

Critical fire weather—dry conditions and gusty winds—is expected to resume on Friday and stretch into the weekend.

While thousands were initially evacuated, several communities in the northwestern region including Angel Fire, Vadito, Placita, Rio Pueblo, Rock Wall, Las Mochas and Sipapu, have been downgraded to “ready” and residents have been allowed to return. Other areas remain under mandatory evacuation.

Smoke from the Hermits Peak/Calf Canyon Fire billows over the mountains near Tres Ritos on May 14, 2022.

Danger Zone

Discouraged and displaced Northern New Mexicans bear the brunt of fire’s destruction

BY JEFF PROCTOR AND WILLIAM MELHADO

MORA—Herman Romero was born a rancher—the fourth-generation kind.

The 60-year-old makes his home in tiny La Cueva, about 5 miles south of Mora. He makes his living in Chacon, 20 miles the other side of town, on a 400-acre spread that has been in his family since the 1800s. Romero has been working the ranch himself for more than three decades; these days, he runs about 65 head of bulls and heifers, plus another 40 calves.

So when the Hermits Peak/Calf Canyon Fire began its merciless march through the area last month and government officials ordered evacuations, there was never a question for Romero.

And Romero hasn’t left since the blaze began eight weeks ago. Standing on his ranch split by Highway 121, Romero’s property spans the valley and evidence of the ongoing fire is everywhere.

A hot, active fire churns out thick, white and black smoke to the south; a mosaic of charred trees and green ponderosas, not fully burned, coats the eastern slope of Romero’s ranch, a former home, now twisted and scorched into a pile of corrugated roofing and bricks.

Romero isn’t throwing a hurricane party—the sort you might’ve read about in the runup to Katrina, Hugo or other large-scale disasters that sent clear, advance signals to either leave or die. Rather, like many others who live an agrarian lifestyle that’s foreign to many New Mexicans in this county of 4,500 people, he easily and angrily rolls out a litany of concerns about the government’s actions before and during the largest wildfire in state history as he explains his reasons for staying.

Romero and others who spoke with SFR question the decision to try a controlled burn—a conservation strategy that went sideways this time, ultimately leading to this mega-blaze—in the brutal April winds of this Northern New Mexico spring. They struggle with the complicated government prohibitions on resident-led thinning. They criticize the “back-burning” techniques employed to demolish fuel sources once the fire was already cooking. And they can’t imagine why they haven’t been allowed to access their lands during the month-plus since the fire started burning.

He does not believe either of his properties is still in danger, but Forest Service and State Police officials have kept Romero from traveling back and forth between them.

“We’ve had some serious problems,” he says. “I’ve had a helluva time getting up [to the ranch in Chacon] with all the roadblocks and the obnoxious law enforcement people… But I know this country like the back of my hand. I know ways in and out of different areas; some of them are legal, some are not, but for your livelihood, you have to do what you have to do.”

Romero is a former Type-1 hotshot firefighter, and he’s never seen tactics like those deployed to tackle this blaze. He’s careful to distinguish between those giving the orders and those on the ground doing the work as he questions why so many Type-1 designates appear to be working from pickup trucks and why upwards of 20 bulldozers meant to cut suppression lines are instead sitting on the backs of trailers.

As for the back-burning strategy, in which officials are igniting what they consider to be easy tinder for the fire?

An exasperated Art Vigil has just returned from the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s temporary office at the Las Vegas evacuation center, located at the for-

WILLIAM MELHADO

TOP: Herman Romero (left) and his son, Emilio, stand on a dozer line cut across their property while watching smoke rise in the distance. MIDDLE: Half of a property near Ledoux was spared from the fire that ripped through the valley last week. BOTTOM: While Romero managed to protect the structures on his property, neighboring homes weren’t so lucky.

mer Memorial Middle School. His home on Highway 94 was destroyed by the fire.

Like many others, Vigil expressed skepticism over FEMA’s process to provide financial relief. The complicated procedure to secure grants has left many feeling that no compensation will be enough.

The most recent numbers from Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham’s office show that about 2,700 applications have been submitted to FEMA. Of those, 702 households have received some portion of the $1.8 million approved assistance.

The governor’s office estimated close to 650 structures have been destroyed in the fire.

Kevin Skillen and his wife, April, live just over the hill from Mora proper, with seven horses, seven goats, three cows and a host of dogs and cats. April evacuated, along with the goats, around May 1 to her childhood home, where her mother still lives in Santa Fe. Kevin stayed behind to help neighbors—he’s got a powerful generator, so he was able to offer fresh water, hot showers and more to the people he’s shared space with for the two years since the couple relocated to New Mexico from Northern California.

Kevin offers a clear, sharp assessment of who he believes should pay to rebuild what’s been lost.

“The federal government started this fire, and they should take 100% responsibility for fixing what’s left to be fixed,” he tells SFR.

His wife has strong opinions on government conservation tactics, too.

Romero and his son, Emilio, haven’t lost their boisterous sense of humor since the fire took so much from their community. But upon seeing the husk of a neighbor’s home, one whose fields they cut in previous years, they fall quiet.

Romero doesn’t expect the forests to grow back in his lifetime.

“But maybe in my grandkids’ lives,” he says.

WILLIAM MELHADO

TOP: Older Northern New Mexicans noted the fire’s devastation would forever alter the forests they grew up with. BOTTOM: At the Las Vegas evacuation center at the former Memorial Middle School, evacuees found a place to sleep and a hot meal while National Guard members helped distribute supplies.

Close to Home

Pecos edges toward evacuation, but fire officials not predicting a big push toward Santa Fe

BY WILLIAM MELHADO

Viola Gonzales-Avant stepped outside her home last week, into the stillcool evening air and noticed some lights on the ridge to the east of her home in Pecos. She didn’t recognize the lights on the hill that stood out against the dark wilderness of the Pecos River Valley.

It then dawned on her, the lights weren’t from a home or car.

“When you can see flames at night, that’s the big eye opener,” Gonzales-Avant tells SFR, standing next to the hand-painted sign thanking firefighters for their work and hanging from a metal gate spun open for drivers on NM Highway 50 to see.

Gonzales-Avant, like almost every Northern New Mexican, has kept a close eye on the fires for the last month, but it seemed distant. When flames crested the ridge, the fire’s proximity became much more apparent. Evacuations in Bull Canyon and Cow Creek, areas she’s very familiar with, are less than 5 miles from her home.

The woman who was raised in the Pecos community wanted to show her appreciation for the firefighters working 12-hour shifts, protecting her childhood home, where she still lives. “My heart is here,” Gonzales-Avant says on a hot afternoon, monitoring the

CONTINUED ON PAGE 15

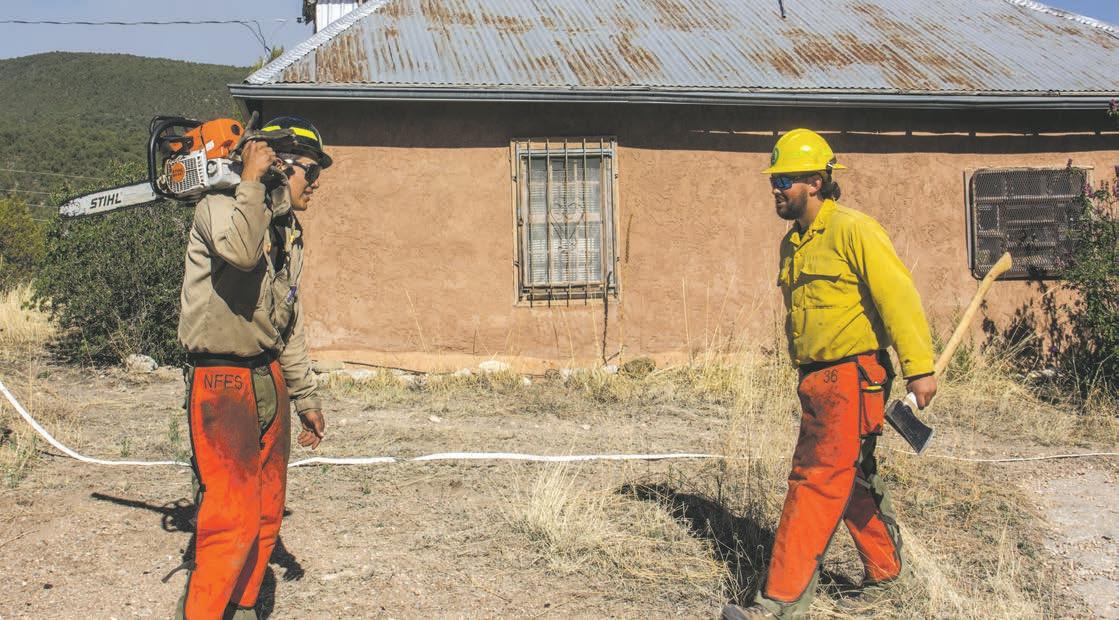

TOP: Members of a Type-6 engine from Montana worked to protect structures east of Pecos, where they removed fuels and installed sprinklers around homes. BOTTOM: Sprinklers pull water from “pumpkins,” seen here in front of a church that sits near the intersection of Bull and Cow creeks.

-Santa Fe County Fire Chief Jackie Lindsey

smoke hanging thick on the horizon with a pair of binoculars. “We need to bear witness to what is going on.”

Over the weekend, emergency managers upgraded the evacuation statuses for the larger Pecos community. Authorities told residents of upper Pecos River Valley—from Holy Ghost to Lower La Posada—to evacuate, while the village proper was elevated to “set” status.

Just west across the county line, one area in Santa Fe County was put in “go” status. The Santa Fe County Sheriff asked residents of Upper Dalton Canyon, a narrow, single-access valley, to evacuate.

Officials say things still look good for Santa Fe County, but that could change.

“We are in extreme drought. We have fire behavior and…such dry fuels out there that any little fire can really grow quickly,” says Santa Fe County Fire Chief Jackie Lindsey.

Working with the Sheriff’s Department, emergency managers and fire officials, Lindsey says, “A lot of variables go into deciding who is going to be put into what status.”

Lindsey notes that weather and topography continue to drive the fire, which makes predicting its movement difficult. She encourages all Santa Fe County residents to stay alert of changes to evacuation statuses.

While the fire’s northern expansion has continued to be fastest moving, the southwest flank is still expected to spread. However, Fire Behavior Analyst Stewart Turner has classified that motion as likely “limited.”

Turner said the fire made two runs over the weekend near Colonias Canyon towards Pecos, which he described as the most problematic area. The fire, Turner said in Monday evening’s update, is burning hot in this area and he expects “to see some smoke outta here but I don’t think you’re going to see any growth outside of the containment lines.”

Last week, fire crews were in this area establishing structural protections for homes that had been evacuated.

Two dogs with short, heavy fur pad up to Will Triplett and his fellow crew members from Montana as they break from installing sprinklers and cutting trees near homes east of Pecos.

Triplett’s crew leader pours some water into the head of a shovel for the dogs to drink.

The surrounding trees, like the dogs, are thirsty. In combination with the dry soils that kick up a dust, coating the surrounding vegetation, the piñon, juniper and ponderosa trees are brittle to the touch.

“There’s more moisture content in the lumber at Home Depot in Santa Fe than there is in these trees,” Triplett tells SFR.

Given the extreme dryness in the fuels, Triplett says his team is focusing efforts on protecting structures.

In the event the fire makes it farther west into Santa Fe County or future fires begin during the not-yet-started fire season, officials ask that residents prepare by protecting their homes with defensible spaces and sign up for emergency alerts.

In an effort to prevent more fires from beginning during the fire season, Santa Fe County closed four trail systems—Arroyo del la Piedra Open Space; Little Tesuque Creek Open Space; Rio en Medio Open Space; and Talaya Hill Open Space—following the closure of Santa Fe, Carson and Cibola National Forests.