151 minute read

to boldness Reviewed by David Woodbury

Reviewed by David Woodbury

Advertisement

David Malcolm Bennett, Catherine Booth: From timidity to boldness 1829 – 1865, (Sydney, Australia: Morning Star Publishing, 2020), 308 pp. ISBN 978 0 64753 072 61

Cover of David Malcolm Bennett’s book, Catherine Booth

The problem with writing about William and Catherine Booth is the simple fact that much has already been written, and a great deal of information is currently available, some factual, some legendary and some folklore. The latest offering on the life and influence of Catherine Booth comes from a writer who has devoted much of his life to researching and writing on the Booths and the early Salvation Army. It is the first of a two-volume biography which explores the life of Catherine Booth, a highly complex yet remarkable woman. While much of the narrative is known through the works of other writers, Bennett breaks new ground, particularly in researching Catherine’s family of origin, the Mumfords. There are some strong emerging themes; such as the methods the Booths began to employ in reaching the lost; street parades before the service, the altar call. Notable, also is Catherine’s conviction on female ministry and the development of the Booth’s team ministry. Bennett notes the use of the term; the prosecution of our mission, in one of Catherine’s letters. He goes on to write: “Though Catherine was not yet preaching she was still sharing in the efforts … To win men and women to the Kingdom of God”.2 By 1861, William and Catherine Booth were in shared ministry with Catherine commenting: “I am just in my element in the work. I only regret that I did not commence years ago”.3 She was to comment later: “I am wonderfully delivered from all fear after I get my mouth open”. It may well be

Reference citation of this paper: David Woodbury, “Book review, Catherine Booth – From timidity to boldness”, The Australasian journal of Salvation Army history, 6, 1, 2021, 92 – 93.

1 At the time of publication of the AJSAH, the book was available online or instore at the following locations; the publisher https://morningstarpublishing.net.au/product/catherine-booth-2/; Koorong https://www.koorong.com/product/catherine-booth-from-timidity-to-boldness-1829-1865_9780647530726 2 David Malcolm Bennett, Catherine Booth: From timidity to boldness 1829 – 1865, (Sydney, Australia: Morning Star Publishing, 2020), 139. 3 Bennett, Catherine Booth, 200.

this realisation of a team ministry impacted the Army in its insistence that married candidates for officership must both receive the call to full-time ministry. Bennett also explores Catherine’s venture into one to one ministry, no doubt a great leap of faith for one so timid and frail. It seems to coincide with her first public preaching at Gateshead. On her way to hear another preacher she “chanced to look up at the thick rows of small windows … where numbers of women were sitting, peering through at the passers-by, or listlessly gossiping with each other”.4 Overcoming her timid nature, Catherine engaged them in conversation and a notable home ministry followed. In this book Catherine comes across as a warts and all real person, complete with idiosyncrasies. Timid? Well perhaps by nature, but fearless and focused, often obsessed with her own health and death, judgmental, tactless and outspoken, yet compassionate, Catherine Mumford was a highly complex and multifaceted personality who was to emerge as perhaps one of the most outstanding women in Victorian England. It may well be that her early death deprived her of the recognition she so rightly deserved. It is a story that once again proves that God will use those who are totally committed to Him. A must read for those interested in the birth and development of The Salvation Army.

4 Bennett, Catherine Booth, 174.

Winning certificate from the Los Angeles Film Awards for Legacy by Hayley Jean Reeves

Images of Commissioners Charles and May Duncan (left and right) the main characters of Legacy and screenwriter, Hayley Jean Reeves (centre)1

1 Images courtesy of the author.

Hayley Jean Reeves

I became interested in my family’s connection with The Salvation Army. This interest became a hobby and I began to research my great grandparents, Commissioners Charles and May Duncan. I followed their appointments throughout Australia, South America and the United Kingdom. After collecting information from the public domain, then exhausting this avenue, I contacted Salvation Army historians. Museum directors from The Salvation Army collections in Melbourne, Sydney (Australia), London (United Kingdom), Wellington (New Zealand) and placed in South America were all consulted to collect information on the Duncan family. The material collected gave a deep insight into the life and ministry of the Duncan family. I produced a book for the family that contained the story of my great grandparents and this impacted me so much, I wrote a screenplay. The screenplay is titled Legacy. Legacy has received special mention in several international competitions and in October 2019, the screenplay was announced as one of the finalists in the Los Angeles Film Awards, USA. Legacy went on to win “Best First Time Screenwriter (Feature)”.

“There is always a narrative that leads to a specific occurrence. Strategic historical threads of people and events influence outcomes to a greater or lesser degree and eventually link together to create a patchwork which bring forth the occurrence.”2

I have experienced this in its true sense and in reverse, that is narratives have led to a specific occurrence, and specific occurrences that have led to the narrative. This narrative was the stories I stumbled upon about my great grandparents, Commissioners Charles and May Duncan, which led to the occurrence being the screenplay, Legacy. These stories told of their service, people they influenced, and their profound effect on hundreds of thousands of lives worldwide. Conversely, the occurrences were the synchronicities during the process of research and writing the screenplay which led to the narrative, Legacy. The synchronicities refer to “accidently” stumbling upon valuable material at the very time that I needed it. When Garth Hentzschel first asked me if I would write a paper for this journal on my methodology of how I turned the history of my great grandparents into a screenplay, I was stumped. I could not pinpoint it at all. It just happened.

After much reflection, I realised it wasn’t just one thing. It was the multitude of synchronicities that occurred, contributing to the project. I was just the vector which allowed it to be materialised. An example of this was one scene in Legacy set in the 1940s of a wedding that my great grandfather was officiating. As he was such a renowned speaker, I had great hesitation in writing his dialogue throughout the screenplay but especially for this particular scene. Furthermore, my

Reference citation of this paper: Hayley Jean Reeves, “Salvation Army history news: Turning the pages of history for the silver screen”, The Australasian journal of Salvation Army history, 6, 1, 2021, 94 – 96.

2 Garth R. Hentzschel, “The development of The Australian journal Of Salvation Army history”, Booth’s Drum, The newsletter of the SA Historical and Philatelic Association – Recording, researching and preserving Salvation Army heritage worldwide newsletter 19, (Winter 2018).

enormous reluctance in writing the scene was compounded by my unfamiliarity with Salvation Army wedding procedures. I mentioned this to a cousin of mine and it “just so happens” that days before she had remembered that she was in possession of Commissioner Charles Duncan’s actual ceremonies book with his hand written notes in the back which he referred to when conducting weddings. She sent photos of this to me and, as such, I commenced writing the scene with ease. Another synchronicity was that a different cousin was friends with Hentzschel who obviously is the editor of this journal and has a vast knowledge of Salvation Army history. Any questions I had, I would put to Hentzschel and he would always have the answers. So many other synchronicities occurred.

When I commenced researching into Commissioners Charles and May Duncan’s involvement in The Salvation Army and the history of the movement as a whole, it wasn’t even on my radar to write a screenplay let alone envisage that it would go on to receive accolades or that I present it to film producers for their consideration for production. However, that is exactly what has happened and, to date is still happening. It’s all due to specific occurrences that collectively enabled the narrative, the project to be born and mature.

Legacy had and continues to have a life of its own. Watch this space.

The LAFA trophy won by Hayley Jean Reeves3

3 Image courtesy of the author.

A SALVATIONIST ARTIST GEORGE HOLLOWAY

Garth R. Hentzschel

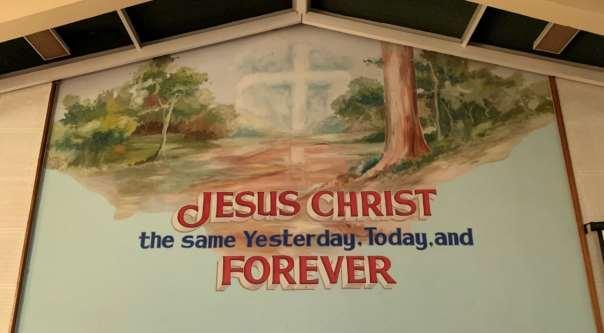

As an infant, I attended the Dee Why Corps of The Salvation Army on the northern beaches of Sydney, New South Wales. I remember standing on the platform during Primary demonstrations1 and looking at the front wall to see a mural towering above me. The cloud formation depicted a cross, which appeared to have arisen above a creek bed. The creek was typical of any that one would see throughout Australia. The main words were in the three-dimensional form which seemed to lift off the surface of the wall; “Jesus Christ, the same yesterday, today and forever.” The words, the image and the name of the artist, George Holloway, have always remained in my mind; but who was Holloway?

A painting by George Holloway in The Salvation Army Dee Why Citadel2

While much of The Salvation Army’s culture transplants itself into any country in which it ministers, there are some unique elements across regions. In many Army halls throughout Australia that were in use during the mid-twentieth century, there was painted on the wall above the platform a verse of scripture on a background of different scenes. Two of the major artists who painted these texts where Salvationists Frank Shaw and Frederick George Holloway. While much has been written on Salvationists who contributed their gifts to God through the Army in the areas of preaching, social work, and the performing arts, especially music; little has been investigated to uncover the lives and ministry of painters and other visual artists. Yet such gifts are also important to God and The Salvation Army.

Reference citation of this paper; Garth R. Hentzschel, “‘A Salvationist artist: George Holloway”, The Australasian journal of Salvation Army history, 6, 1, 2021, 97 – 120.

1 Primary was a Sunday School for young children and each year at the Young Peoples’ Anniversary would hold a Sunday afternoon demonstration, or songs and activities to show parents what had been done over the previous year. Awards in the shape of books were also presented to children who had attended. 2 Photograph courtesy Captain Marrianne Schryver.

Cadet George Holloway3

3 Cadet George Holloway’s image from Dedicating and commission services of the “Blazer” session of cadets, (Sydney, The Salvation Army Australia Eastern Territory, 1931).

In a letter written to soldiers of The Salvation Army, General William Booth wrote,

Suppose a man is by nature an artist. He can sketch: he can make pictures full of life and naturalness and beauty. What is he to do with it? Neglect it? By no means. Draw and engrave and paint in order to make a fame or a fortune? Certainly not. Well, what is he to do? Consecrate his gift. This is an age of pictures. Men have not only been amused but taught by them in all ages of the world. … Let us have them for the Kingdom of God. Put the blessedness of Salvation, the cursedness of sin, the glory of Heaven and the dreadfulness of Hell in living forms and shapes before men. Let us have “Salvation Graphics” in every land to equal or excel anything that the world can produce…4

Creating ‘Salvation Graphics’ was what Shaw and Holloway attempted to do. The life and ministry of Shaw is being investigated, as his ministry has not previously been recorded. 5 Similarly, Holloway has largely been neglected by historians and only listed in relation to his Red Shield War Service. 6

As with many Salvationists, Holloway’s personal life and ministry has been difficult to trace, apart from his time as an officer. The information that has come to light reveals that Holloway used his artistic talents to “Put the blessedness of Salvation, the cursedness of sin, the glory of Heaven and the dreadfulness of Hell in living forms and shapes before men”.7 Holloway also used his talents to bring people’s attention and finances to The Salvation Army.

Early life

After much effort to locate personal information, it is believed that Frederick George Holloway was born to Eliza (Lillian) Hephzibah (nee Thorn)(1874 – 1918) and Frederick William Holloway (1873 – 1953) at Christchurch, England on 28 November 1908. 8 Searches online failed to show anything on the early life of Holloway. A difficulty was that there were several people identified in newspapers with the name of “George Holloway” and “Frederick George Holloway”. These names linked to topics ranging from school examination results, divorce proceedings, and carrying a gun without a licence; none of these could be found to relate to the person under investigation. Although contemporary Salvation Army publications list Holloway as “Frederick”,9 newspapers and The war cry of the time, and people who remembered him would more often use “George”.10

4 William Booth, “The General’s letter”, The war cry, (London, Saturday 21 March 1885), 1. 5 Garth R. Hentzschel and Glenda Hentzschel, working title, “The mark of quality on every job:” The life and work of a Salvationist artist, Frank Herbert Shaw. 6 Cox and Hull listed “Frederick Holloway” in a list of Red Shield War Services Representatives during World War Two, however nothing else was included in their publications on Holloway. Some information on Holloway was also included in Under the tricolour, although the item by Callaghan held a few minor errors. Lindsay Cox, Cuppa tea, Digger? Salvos serving in World War Two, (Victoria, Australia: Salvo Publishing, The Salvation Army, 2020), 221.; Walter Hull, Salvos with the forces, Red Shield Services during World War Two, (Hawthorn, Australia: The Salvation Army, 1995), 294. There were also illustrations by Holloway in Under the tricolour, “Sketches from an autograph book”, Under the tricolour, 37, (April-June 2009), 7 – 9.; Don Callaghan, “A recent arrival at the museum”, Under the tricolour, 80, (September 2020), 7 – 8. 7 Booth, “The General’s letter”, 1. 8 Information received with assistance from Major Kingsley Sampson and ancestry.com.au. Queensland births, deaths and marriages note the mother as Lillian Thorne and farther William Henry Frederick. https://www.familyhistory.bdm.qld.gov.au/ accessed 19 February 2021. 9 Sometimes Holloway’s first name, Frederick was used, see for example “Official gazette”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 21 June 1941), 4.; Walter Hull, Salvos with the forces. Red Shield Services during World War 2, (Mount Albert, Australia: The Salvation Army Australia Southern Territory, 1995), 294. However more often he was known as George Holloway. 10 See for example. “Salvation Army”, The Armidale express and New England general advertiser, (NSW, Friday 26 May 1933), 8.; “Final Easter news reports”, The musician, (Australia, 28 May 1966), 80.

A story from the Shaw family stated that Holloway arrived in Australia with his brother Bill and did his apprenticeship with Salvationist sign writer, Frank Shaw. It has not been established when this took place, or if his time with Shaw attracted Holloway to The Salvation Army.11 It has however been found that his brother, William Henry Holloway, born in 1912 did come to Australia and passed away in Toowoomba, Queensland on 29 January 1963.12

Training as a Salvation Army officer

George Holloway entered The Salvation Army’s Training Garrison, Sydney, in the 1930 “Blazer” session. 13 The war cry and the commissioning booklet noted that Holloway went to training from the Manly Corps, 14 situated in a beach-side suburb of northern Sydney. The first record of Holloway’s practical training was with other cadets at the Goulburn Corps for “the Easter Campaign”. Goulburn is a regional city about 90 km from Canberra. Here Holloway participated in indoor meetings, visitation, music festivals, and open-air meetings. These meetings were the first indication of Holloway’s artistic skills as he created a “black-board sketch” at both indoor and out-door meetings.15 Other reports on Holloway’s training had him at inner Sydney corps, including Rockdale and Sydney Congress Hall, where he participated in several meetings. While this paper will focus on Holloway’s visual arts, it needs to be stated that he also had other artistic gifts, for example, at Congress Hall Holloway sang “a solo of his own composition”. It appears that the words and music have been lost to history and this was the only time he composed a song.16 His artwork was also described at this time as “the chief attraction” which consisted of “a black-board lesson by the Cadet, who illustrated his talk on the Pearl of Greatest Prize with rapidly changing pictures.”17 Holloway was intelligent, as at commissioning it was announced that he received some of the highest marks in the examinations. His training had shown the importance of consecrating his artistic gifts to the service of God. It was obvious to him, as observed by another officer, “if we wish our contemporaries to heed the message let us remember that they need to see as well as hear if their attention is to be captured.”18

Early Salvation Army officership

Holloway was commissioned with the rank of Probationary Lieutenant and appointed to Haberfield Corps as assistant officer.19 The corps was situated in the inner West of Sydney. His arrival and talents were soon reported in The war cry,

The attendances at meetings, both indoor and out are on the upgrade at Haberfield, and there is a spirit of unity amongst our small but loyal band of Soldiers. The Friday open-air meeting is a blessing and the Lieutenant’s blackboard sketches attract an interested audience.20

11 Interview between Major Fred Shaw and Major Glenda and Kevin Hentzschel, (Monday 17 February 2020). 12 Ancestry.com.au. 13 “The ‘Blazer’ session takes the field”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 24 January 1931), 9. 14 “The field”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 6 July 1935), 12.; Dedicating and commission services of the “Blazer” session of cadets, (Sydney, The Salvation Army Australia Eastern Territory, 1931). 15 “Goulburn’s Easter battles”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 10 May 1930), 10. 16 Holloway would later return to the corps to run the testimony section of a meeting, to read from the scriptures, and to give a talk. “Congress Hall”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 3 November 1930), 4.; “Congress Hall”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 15 November 1930), 4.; “Congress Hall”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 13 December 1930), 4.; “Congress Hall”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 24 January 1931), 13. 17 “Rockdale”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 18 October 1930), 4. 18 D.E.G., “Louder than words”, The officer, 31, 5, (May 1980), 228-229, 229. 19 “The ‘Blazer’ session takes the field”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 24 January 1931), 9. 20 “Haberfield”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 4 April 1931), 13.

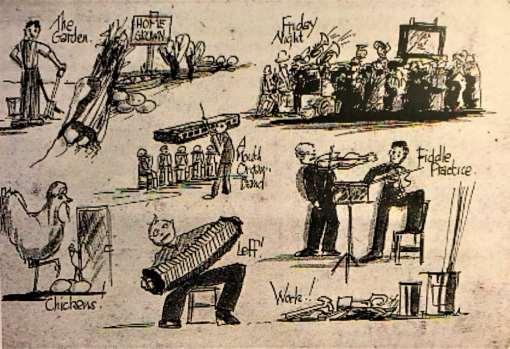

While at Haberfield, Holloway used his sketches to assist at other Sydney suburban corps, such as Newtown and Paddington Corps. 21 Sadly many of Holloway’s drawings no longer exist, however while at Haberfield he recorded many of his duties as a lieutenant or “Leff” in the autograph book of his captain. These drawings included domestic chores, after school meetings, and musical practices. They also showed Holloway could play a brass instrument, a mouthorgan, a concertina, and a fiddle.

Images drawn by George Holloway to show the life of an assistant corps officer22

21 “Newtown”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 25 April 1931), 12.; “Paddington”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 19 September 1931), 12. 22 Autograph book of Captain Edward Merrick, housed in The Salvation Army Australia Museum, Sydney, cited in “Sketches from an autograph book”, 7 – 9.; Callaghan, “A recent arrival at the museum”, 7 – 8.

From Haberfield Corps, Holloway was appointed to the finance department of Sydney Central Division’s headquarters.23 During this appointment he was a ‘special’24 at corps throughout Sydney and to its north. At each corps he used his “lightning sketches” to show “Bible Truths”. Some of the Sydney corps visited by Holloway where he used his artistic skills included Balmain, Bexley, Campsie, Daceyville, Hornsby, Liverpool, Mortdale, North Sydney, Paddington, Petersham, Rockdale, Rozelle, Ryde, Sydney Congress Hall, Waterloo, Waverly and Willoughby. Sadly, many of these corps no longer exist. Holloway’s artistic skills were used for corps cadet rallies, a Daffodil Fair, evangelical and revival campaigns, harvest festivals, holiness meetings, indoor meetings, openairs, programmes, self-denial fund raising efforts, spiritual campaigns, and young peoples’ meetings. At most of these meetings Holloway saw people, young and old come to the mercy seat to receive Christ as their Saviour. He also assisted at churches such as the Methodist church at North Croydon.25

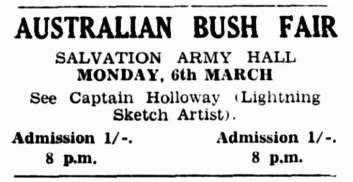

Advertisement showing Holloway preaching at Sydney Congress Hall in connection with a Harvest Festival in March 193226

Upon the promotion to captain, most officers removed their yellow Lieutenant braiding to replace it with a red braid, but not Holloway. 27 Being the artist he was, Holloway painted his trimmings on his uniform. The war cry reported,

Of a decided artistic turn is the young Officer who was seen at his desk at Territorial Headquarters, with paint and brush changing the colour of the braid on his tunic. Only a skilful hand would essay such a delicate task, but Captain George Holloway, promoted to the rank, was making a good job of it. The Captain is known all over Sydney for his Bible object lessons with paint and brush.28

23 “Official gazette”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 30 January 1932), 8.; “Mainly about people”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 30 January 1932), 8. 24 A term used for visiting speakers at Salvation Army meetings. Such meetings were usually advertised and used to motivate local Salvationists or to encourage new people to attend Salvation Army meetings. 25 See for example, “Congress hall”, The war cry, (Sydney, 13 February 1932), 12.; “Religious announcements”, The St George call, (Kogarah, Friday 4 March 1932), 2.; “Other services”, The Sydney morning herald, (NSW, Saturday 5 March 1932), 5.; “Paddington (NSW)”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 12 March 1932), 13.; “Corps-cadets take the field”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 19 March 1932), 13.; “Coming events”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 2 April 1932), 13.; “Congress hall”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 16 April 1932), 14.; “Waterloo”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 16 April 1932), 14.; “Congress hall”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 21 May 1932), 12.; “Coming events”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 28 May 1932), 13.; “Coming events”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 4 June 1932), 13.; “Coming events”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 11 June 1932), 13.; “Coming events”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 18 June 1932), 13.; “Crusade progress”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 25 June 1932), 8.; “Campsie”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 2 July 1932), 12.; “Revival crusaders”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 30 July 1932), 9.; “Waverly”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 6 August 1932), 12.; “Coming events”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 6 August 1932), 13.; “Daffodil fair”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 3 September 1932), 13.; “Hornsby”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 22 October 1932), 16.; “Willoughby tent campaign”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 10 December 1932), 13.; “North Croydon Institute”, The Methodist, (Sydney, Saturday 3 September 1932), 11. 26 “Other services”, The Sydney morning herald, (NSW, Saturday 5 March 1932), 5. 27 “Official gazette”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 28 January 1933), 8. 28 The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 21 January 1933), 10.

Although a change of appointment could not be located, it appeared that Holloway had been appointed to Territorial Headquarters (THQ), Sydney. Soon after Holloway became a captain, he was involved in a failed rescue attempt. The Manly ferry left its jetty at 9:15pm and when it was between the Sydney Heads a man went overboard. A lifeboat was launched, but when the man was found and taken back to the ferry, he was unconscious. The passengers of the ferry attempted to revive the man. The daily telegraph continued its report and stated,

One of those who worked tirelessly to try and restore animation was Captain Holloway of the Salvation Army. He did not know at the time that the man had frequently occupied a room at the Army Hostel, and that in his pocket was a will leaving all he possessed to the Salvation Army.

Sadly, the man was not able to be revived and was pronounced dead. 29 While he was stationed at THQ, Holloway continued to support corps around Sydney including Botany Corps30 and Balmain Corps. At Balmain he assisted in a children’s campaign where his “‘lightening sketch’ attracted old and young.”31 From THQ, Holloway was sent to be the assistant officer at Armidale Corps, located about halfway between Brisbane and Sydney. A farewell report gave positive comments of his artistic skills,

Captain George Holloway, of Territorial Headquarters, has been appointed to Armidale Corps to Assist. The smaller Corps around Sydney will miss the Captain, who has been a constant Special, both interesting and instructing congregations with his crayon sketches of Bible stories and parables.32

Following Armidale Corps, Holloway received a number of short-term appointments; Mayfield Corps33 and Bexley Corps,34 both inner city corps of Sydney, and then Deniliquin Corps, 35 a town close to the NSW/ Victorian boarder. At many of these corps, Holloway was reported as having conducted his talk with artistic sketches.36

The marriage of Holloway

From Deniliquin, Holloway was appointed to Nowra Corps on the south coast of NSW.37 While stationed at Nowra, on 10 April 1935, Holloway married Captain Dorothy Isobel Mary Hoffman. Hoffman had entered The Salvation Army Officer Training college from Willoughby, NSW in 1931 and was stationed at Griffith Corps at the time of their marriage.38 A local paper pointed out that

29 “Man drowned from ferry off the Heads”, The daily telegraph, (Sydney, Thursday 16 March 1933), 1. 30 “Botany”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 29 April 1933), 7. 31 “Balmain”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 25 March 1933), 7. 32 “Mainly about people”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 22 April 1933), 10. 33 “Mainly about people”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 17 June 1933), 11.; “Mayfield”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 13 January 1934), 12.; “Mayfield”, Newcastle morning herald and miners’ advocate, (NSW, Saturday 10 June 1933), 3. 34 “The field”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 2 December 1933), 10. 35 “Deniliquin”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 14 April 1934), 7.; “Salvation Army”, The independent, (Deniliquin, Friday 19 January 1934), 4.; “Salvation Army”, The independent, (Deniliquin, Friday 29 June 1934), 4. 36 See for example, “Tighe’s Hill”, Newcastle morning herald and miners’ advocate, (Thursday 17 August 1933), 13.; “Shortland”, Newcastle morning herald and miners’ advocate, (Saturday 30 September 1933), 4. 37 “The field”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 9 March 1935), 12.; “Nowra”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 6 April 1935), 12.; “Personal”, The Shoalhaven telegraph, (NSW, Wednesday 23 January 1935), 2.; “Advertising”, The Nowra leader, (NSW, Friday 1 February 1935), 3. 38 “The field”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 6 July 1935), 12.

Holloway had “made quite a number of friends during his comparatively short stay in Nowra.” While he knew that as a married couple, they would receive a new appointment, they were not told where.39 The war cry carried a report on the wedding and pointed out that the local newspaper had included the ceremony in its pages. The war cry stated,

OFFICERS’ WEDDING Captain George Holloway and Captain Dorothy Hoffman Nowra Hall was filled with people for the wedding of Captain George Holloway and Captain Dorothy Hoffman. Lieutenant Hocking attended the bride, and Lieutenant Fischle supported the bridegroom. Major Taylor conducted the wedding, which the local paper, in a lengthy report, says was “in accordance with The Salvation Army regulations, and very impressive.”40 Hearty congratulations and the best of good wishes were passed on to the Captain and Mrs. Holloway at an after-gathering, where the Rev. M. Newton (for the Churches), Sergeant-Major Faulks (for the Corps), Lieutenant Hocking (for Griffith Corps), spoke. A large number of telegraphed greetings were read.41

From the time of their wedding to February 1936, the couple were stationed at Rozelle Corps, then another inner-city Sydney corps. 42 They then were appointed to Sandgate Corps, Queensland (Qld), a northern coastal suburb of Brisbane, where they soon engaged in all aspects of the corps. 43

Queensland corps work

Information from this time again showed Holloway’s artistic ability and his use of his artwork in meetings. At the Easter service, “[a] sketch will be given by Captain Holloway of Sandgate, picturing the scene of Calvary, while the West End songsters will sing ‘The Old Rugged Cross.’”44 During the State Congress he did a lightning sketch, “In Memory of the Founder”, William Booth.45 For Christmas, Brisbane Salvationists held a musical festival and “[t]he closing special feature was a Christmas sketch by Captain Holloway, who portrayed the story of the Wise Men and the Star”.46 On 7 October 1937, Holloway commenced his appointment at Boonah Corps, Qld, a rural town about 80 km south-west of Brisbane.47 At the welcoming ‘social’, the corps folks played games, participated in competitions and “[a] feature was a series of blackboard sketches by Capt. Holloway.”48 Being a rural area, many activities of The Salvation Army were reported in the regional newspaper, allowing more actions of Holloway to be identified. The Boonah Corps’ Young Peoples’

39 “Personal”, The Nowra leader, (NSW, Friday 5 April 1935), 4.; “Local and general”, The Shoalhaven news and South Coast district advertiser, (NSW, Saturday 6 April 1935), 2. 40 While much of this quotation appeared in two local newspapers, The war cry inserted the word “very”. “Salvation Army wedding”, The Shoalhaven news and South Coast districts advertiser, (NSW, Saturday 13 April 1935), 3.; “Salvation Army wedding”, The Nowra leader, (NSW, Friday 19 April 1935), 1. 41 “Officers’ wedding”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 11 May 1935), 13. 42 “The Field”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 18 May 1935), 12.; “Rozelle”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 11 January 1936), 12. 43 “The field”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 15 February 1936), 15.; “Sandgate”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 19 December 1936), 5.; “Contrasts between war and social spending”, The telegraph, (Brisbane, Monday 24 February 1936), 16.; “Salvation Army”, The telegraph, (Brisbane, Saturday 4 April 1936), 21.; “Anzac Day services,” The telegraph, (Brisbane, Friday 24 April 1936), 5. 44 “Salvation Army Easter services”, The telegraph, (Brisbane, Saturday 11 April 1936), 17. 45 “Salvation Army Congress”, The courier-mail, (Brisbane, Tuesday 19 May 1936), 5.; “Salvation Army Congress”, The telegraph, (Brisbane, Tuesday 19 May 1936), 20, 23. 46 “Brisbane Christmas musical festival”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 16 January 1937), 4. 47 The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 9 October 1937), 10.; “Boonah”, The Queensland times, (Ipswich, Thursday 11 November 1937), 12. 48 “Boonah”, The Queensland times, (Ipswich, Thursday 11 November 1937), 12.

Anniversary in December saw Holloway use a different approach to his drawings; he did a “number of sketches of children in the audience”. The program went for nearly two hours and it was reported that “The Salvation Army Hall was inadequate for the accommodation of the large number of people who turned out”.49 The following year, 1938 at the Boonah Corps’ Harvest Festival, Holloway assisted with the decoration of the hall. The Queensland times recorded that,

A large illustration of five horses abreast drawing a reaping machine in a field of wheat was a feature of the decorative effects. This was the handiwork, or, more appropriately, the artistry of Captain Holloway, who is in charge of the local Army Corps.50

Holloway also used his skills at the neighbouring corps, Kalbar where he assisted with the Harvest Festival and later the Self-Denial Appeal. 51 An event in April showed the skills and gifts of both Captain and Mrs Holloway. The corps took the School of Arts hall to run a concert to raise funds. The Queensland times covered the concert and gave high praise for Holloway. In part, the newspaper stated,

The concert was produced by Captain and Mrs. Holloway, both of whom had put a great amount of detailed work into the production, which was obviously enjoyed by the packed house. Several of the items were of special merit, notably those in which Captain Holloway, with pencils and paints, illustrated with rare artistry the song themes of the children. His ability as a black and white artist was well demonstrated in his sketchings of “The Soliloquy of Sally.” During a vocal duet entitled “The Church in the Wildwood” the theme was rapidly illustrated by the Captain in a manner that was in the highest degree entertaining. A descriptive item – Noah’s Ark by the children, was made realistic by animals, moulded in cardboard, gathered around a model of the ark, and characteristic representation of the busy Noah.52

As he had done in Sydney, Holloway assisted churches in the Boonah area with his artistic skills. When the new porch of the Lutheran Church at Dugandan was opened, it was revealed that Holloway had painted the sign “St. Paul’s Lutheran Church, 1889” on the front of the new addition to the church building. Twice in the year, Holloway also assisted the Methodist Church with a sketch described as a “fascinating feature”. In addition to the Lutheran and Methodist churches, he assisted the Church of Christ by presenting a sketch for their Harvest Festival.53

49 “Fassifern district”, The Queensland times, (Ipswich, Tuesday 7 December 1937), 8. 50 “Fassifern district”, The Queensland times, (Ipswich, Tuesday 22 February 1938), 2. 51 “Kalbar”, The Queensland times, (Ipswich, Monday 7 March 1938), 8.; “Kalbar”, The Queensland times, (Ipswich, Friday 23 September 1938), 12. 52 “Fassifern district”, The Queensland times, (Ipswich, Tuesday 12 April 1938), 9. 53 “Porch dedicated”, The Queensland times, (Ipswich, Tuesday 26 April 1938), 6.; “Fassifern district”, The Queensland times, (Ipswich, Saturday 14 May 1938), 14.; “Milford”, The Queensland times, (Ipswich, Thursday 29 September 1938), 12.; “Fassifern district”, The Queensland times, (Ipswich, Friday 31 March 1939), 2.; Aub Podlich and Kirsten Podlich, Dugandan. Our people – our church. A pictorial tribute to the people of Trinity Lutheran Church on the 125th anniversary of the dedication of our church, (Queensland: Lutheran Church of Australia, 2014), 69.

(Left) Image of the sign painted by George Holloway on the Dugandan Lutheran Church (Right) An enlarged section of the photograph showing Holloway’s signwriting54

The war cry contempory to this time showed the powerful effect of Holloway’s drawing. The war cry reported,

The man had been boxing at a local show, and had noticed a copy of The War Cry being passed to a mate of his by the Corps Officer from Kalbar. The man, who had a wound in the centre of his forehead (received in a fighting bout), was later attracted by an Open-air crowd who were watching Captain Holloway, of Boonah, sketching “Sin’s Boomerang,” which showed the boomerang as a wound in the centre of a man’s forehead – the same spot as the boxer’s scar. This so impressed the fighting man that he followed the Captain’s wife to the Quarters, just a little ahead of the Captain, and asked to be instructed in the Way of Salvation. He afterwards left for Melbourne, and the Captain is keeping in touch with him.55

William Booth hoped that ‘Salvation Graphics’ would “equal or excel anything that the world can produce”.56 Holloway’s ability to paint animals and landscapes was clearly seen in a report printed in The Queensland times. The report outlined that Boonah Corps had run an “Aussie Afternoon”, then continued,

Captain G. Holloway had an illustration of a typically Australian scene extended across the back of the platform. Two giant gum trees towered to the roof. Laughing jackasses [kookaburras] were perched on its branches. Life-like paintings of two native bears [koalas] looked down on the audience from the trees, and an old man kangaroo raised his giant bulk nearby. The representations of two native bears [koalas], dressed as an old man and an old woman, carrying their swags, were in the foreground. The shadow effects were done extremely well, and the picture was appropriately named, “On the Sunset Track.”

The report also included that during the concert, Holloway completed a coloured picture of two kookaburras on a blackboard as the laugh of a kookaburra played on a gramophone.57 His quality of artistry was attracting attention!

54 Photograph courtesy of “a current member of Trinity Lutheran Church at Dugandan” and Friends of Lutheran Archives, Queensland (FOLAQ). The people in the photograph requested to remain anonymous. 55 “The boxer and the boomerang”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 9 July 1938), 9. 56 Booth, “The General’s letter”, 1. 57 “Fassifern district”, The Queensland times, (Ipswich, Monday 4 July 1938), 2.

As shown, regular Salvation Army activities staged Holloway’s talents, but so did larger Army events. 58 As with the Christmas musical festival in 1936, Holloway participated in a large divisional event in 1938. During the Young People’s Demonstration in Brisbane Holloway again did his “lightning sketches [which] attracted close attention”.59 The year 1939 was another busy year for Holloway at Boonah Corps:60 he wrote a serial in The war cry called “Not a farmer but a sower of seed”;61 a son, Bernard George Holloway was born on 24 May;62 sketches and back drops were painted for Kalbar Corps’ Self-Denial, Beaudesert Corps’ Bush Fair, and Boonah Corps’ Fete. 63 Holloway was also listed as playing his mouth organ in concerts. 64

Advertisement for George Holloway sketching at Beaudesert65

In 1940, the family were appointed to the Fortitude Valley Corps, Qld, which was an inner-city Brisbane corps.66 This appointment placed Holloway in a good location to be used at combined Salvation Army meetings in Brisbane. First, Holloway was used for the combined Self-Denial Appeal thanksgiving meeting; here he “depicted, by sketching, the various branches of The Army’s work”.67 Second, the combined Brisbane Easter meetings had “[t]he programme … enriched by two sketches by Captain Holloway, ‘The Song of Brother Jones’ and ‘Death to Life’”.68 Third, at the Queensland State Congress, Holloway again took part. The war cry reported,

The Scripture reading, dealing with the parable of the Prodigal Son, was recited by Captain G. Holloway; then, to the playing of The Penitent’s Plea, the Captain sketched scenes’ in the prodigal’s life. The presentation was received in deep silence; the message was personal and powerful.69

58 Holloway drew sketches for Boonah Corps’ Self-Denial fair. “Salvation Army fair”, The Queensland times, (Ipswich, Friday 30 September 1938), 10. 59 “Talents of youth”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 18 June 1938), 7. 60 “All worked enthusiastically”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 18 March 1939), 12. 61 “Not a farmer but a sower of seed”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 20 May 1939), 5. 62 “Personal intelligence”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 22 July 1939), 10.; ancestry.com.au 63 “Kalbar”, The Queensland times, (Ipswich, Thursday 2 March 1939), 2.; “Advertising”, The Beaudesert times, (Qld, Friday 3 March 1939), 4.; “Harvest festival”, The Beaudesert times, (Qld, Friday 10 March 1939), 3.; “Boonah”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 25 November 1939), 4. 64 “Harvest festival”, The Beaudesert times, (Qld, Friday 10 March 1939), 3.; “Fassifern District”, The Queensland times, (Ipswich, Monday 3 July 1939), 3. 65 “Advertising”, The Beaudesert times, (Qld, Friday 3 March 1939), 4. 66 “Official gazette”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 16 September 1939), 8.; “Valley”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 20 January 1940), 4. 67 “SO. [sic] Queensland”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 4 November 1939), 6. 68 “In the Queensland capital”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 6 April 1940), 7. 69 “The standard is high”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 1 June 1940), 10.

At the same Congress, Holloway produced art on the lighter side. In the youth meeting, the Fortitude Valley Corps’ young people presented acts that,

… included lifelike portraits under the lightning brush of Captain George Holloway, and an overalled staff of six young women. The kindly characteristics of General Carpenter were seen, and as a farewell gesture to Lieut.-Commissioner Dalziel, he was depicted with a good measure of exactness.70

Holloway did not just appear at large events, but also assisted in other Salvation Army corps around Brisbane. He painted items for the Caboolture Corps fete, which was to raise funds for SelfDenial.71 It would have been difficult raising money at this stage as there were many similar events being held in the attempt to secure funds for Australia’s war effort. While militaries around the world were engaged in deadly campaigns, in 1941 The Salvation Army in Brisbane was running a series of “beach campaigns” to save souls. At several Queensland seaside resorts, such as Sandgate, Wynnum, and Lota, open-airs and other meetings were held. Of Holloway it was noted, “Captain Holloway, with ready brush, depicted topical events carrying a spiritual message.”72

Holloway family matters

The family was appointed to Nundah Corps, Qld in February 1941, another inner-city corps, this time to the north of Brisbane City and close to their earlier appointment at Sandgate Corps.73 This appointment caused mixed feelings for the family. Soon after their arrival at Nundah Corps The war cry reported, “Captain and Mrs. Holloway, of Nundah, have been very anxious owing to the serious illness of their children, for whom prayer is requested.”74 The children were likely Bernard and newly born (14 February 1941) Ralph Walter Frank Holloway. 75 While at the corps the couple were also promoted to the rank of Adjutant.76 Although the family had had major concerns over their children, The Salvation Army was still using Holloway for large divisional events. Over Easter 1941, a series of combined meetings were planned, and it was stated that in one of these Holloway “proclaimed a powerful message in his skilful sketching of ‘The Seeking Shepherd.’”77 In June, to promote the work of The Salvation Army’s war work and [to] collect funds, a “Women’s war-work exhibition [was held] in Brisbane City Hall”. The report of the event stated, “Adjutant Holloway’s artistic efforts were especially striking. One picture showed a company of children holding a meeting in a London tube railway station.”78 As many of the paintings and drawings of Holloway were not intended to be kept, very few visual examples remain. This “war-work exhibition” was however photographed.

70 “Brisbane youth”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 8 June 1940), 4. 71 “Caboolture’s S. D. fete”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 5 October 1940), 3. 72 “Beach campaigns”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 1 February 1941), 6. 73 “The field”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 22 February 1941), 4.; “Salvation Army officers’ annual changes”, The courier-mail, (Brisbane, Tuesday 7 January 1941), 6. 74 “Eastern Territory”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 8 March 1941), 7. 75 “Personal intelligence”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 19 April 1941), 7. 76 “Personal intelligence”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 10 May 1941), 7.; “Official gazette”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 21 June 1941), 4.; “Salvation Army”, The telegraph, (Brisbane, Saturday 26 April 1941), 18.; “Church notes”, The courier-mail, (Brisbane, Saturday 26 April 1941), 11. 77 “Easter musical festival”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 26 April 1941), 7. 78 “Red Shield display”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 28 June 1941), 7.

“Queensland Red Shield activities in model Red Shield Hut at the Women’s War-Work Exhibition in the Brisbane City Hall” In the background are examples of Holloway’s work79

As shown, illness had hit the children of the family in March 1941, and again in August it was announced the family were concerned about “the ill-health of their children. The baby is in hospital, and Mrs. Holloway has to be in attendance.”80 Sadly, the baby, Ralph Walter Frank Holloway was promoted to Glory on 4 August 1941, he was not yet 6 months old. 81 The family did not have long to grieve as within four months they were again on the move and had to leave the grave of their lost child behind.

Final corps work

In February 1942, the Holloway family were appointed to Kempsey Corps, in the mid north coast of NSW.82 More sadness came to the family while at Kempsey. Their surviving son, Bernard “was badly burned in a primus stove accident, and had treatment in hospital”. At the time it was reported he made “satisfactory progress” but evidently not enough.83 On 6 June another son was born, John Garth Holloway, yet the three-year-old Bernard was unwell and again taken to hospital; a short time later Bernard was promoted to Glory.84 Holloway was also involved in a car accident that put his car out of order just as his work was increasing with the war effort.85 Despite the series of sad events, Holloway continued to work in the corps and started to find ways to assist the growing needs of military troops in the area.

79 “Red Shield display”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 28 June 1941), 4. 80 The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 9 August 1941), 7. 81 Queensland, births, deaths, and marriages, https://www.familyhistory.bdm.qld.gov.au/ accessed 12 February 2021.; “Family notices”, The courier-mail, (Tuesday 5 August 1941), 10.; “Amazing acts”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 23 August 1941), 4.; “Personal intelligence”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 6 September 1941), 5.; ancestry.com.au 82 “Official gazette”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 7 February 1942), 3.; “2 Churches cancel conferences”, The courier-mail, (Brisbane, Saturday 10 January 1942), 6.; The Macleay chronicle, (Qld, Wednesday 21 January 1942), 4. 83 The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 21 March 1942), 7. 84 “Personal intelligence”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 1 August 1942), 5.; “Bernard George Holloway”, The Macleay argus, (Kempsey, Friday 24 July 1942), 2.; “Return thanks”, The Macleay argus, (Kempsey, Tuesday 4 August 1942), 2. 85 “Without a car”, The Macleay argus, (Kempsey, Friday 24 April 1942), 2.; “Our mail bag”, The Macleay argus, (Kempsey, Friday 10 July 1942), 4.

Holloway continued to use his artistic gifts. He contributed vocal and sketching items to the Corps’ Harvest Festival program and other programs run to raise funds for the corps brass band.86 A report on a concert commenced with the subtitle “Fine Entertainment in Salvation Army Hall” and outlined the artwork presented by Holloway,

A remarkable feature of the entertainment was the lightning sketch water color [sic] work of Adjt. G. Holloway. Whilst Mr. H. Williams sang “When I get To The End Of The Road,” the Adjutant quickly sketched a lovely scene with a road leading into the sunset; …

Holloway accompanied two other items with his artistic skills, then,

Messrs. A. Clissold and H. Williams sang “Come to the Church in the Wildwood,” their vocal duet being accompanied by Mr. Alwyn Secomb at the organ; and the artistic effect was greatly enhanced by Adjt. Holloway’s charming sketch of an old English scene with the church nestling by the woodland in the valley. As the artists were applauded a lady in the audience announced that she’d like to buy the sketch, which was sold to her for 2/-. Mr. George Tweddle promptly auctioned the next picture to Mr. Williams for 4/-, whereupon Mr. Williams sold George another for 2/. On the next sheet of paper, Mr. Clissold made a brush sweep which the Adjutant quickly turned into a clever caricature of Mr. Geo. Tweddle handing out new boots for old, and an auction of this picture brought in over £1, all the moneys going to the Band funds. … The Adjutant finished his performance with an excellent sketch entitled “The Prodigal’s Return,” one of the best pictures of the evening.87

As the focus of the Australian war effort shifted from Europe to Asia in 1942, Australia needed to prepare itself for potential invasion. Holloway started to help the town move to a war footing. He began to organise the collection of clothing, “in case of emergency. Should there be raids on Kempsey, with consequent suffering and loss of personal effects”, they had heard about the devastation in Europe and wanted to be prepared. 88 He also helped prepare the community for any first aid needs with the organising of A.R.P. (Air Raid Precautions) lectures.89 Throughout these times Holloway was clear that all people were welcome to come to him “[i]f in trouble of any kind.”90

An example of the advertisements for the Kempsey Corps91

86 “Salvation Army”, The Macleay argus, (Kempsey, Friday 6 March 1942), 4.; “Salvation Army”, The Macleay argus, (Kempsey, Tuesday 19 May 1942), 2. 87 “Concert and play”, The Macleay argus, (Kempsey, Wednesday 20 May 1942), 4. 88 “Clothing for bomb victims”, The Macleay argus, (Kempsey, Wednesday 11 March 1942), 7. 89 “A. R. P. lecture”, The Macleay argus, (Kempsey, Friday 17 April 1942), 4. 90 See for example, “Salvation Army”, The Macleay argus, (Kempsey, Tuesday 19 May 1942), 2. 91 See for example, “Salvation Army”, The Macleay argus, (Kempsey, Tuesday 19 May 1942), 2.

As World War Two continued, The Salvation Army decided to open more work with troops. In July 1942, Major Ralph Satchell, Assistant Commissioner for Red Shield War Services visited Kempsey to arrange for the establishment of a Red Shield Club.92 It appears the first club ran from “Lane’s shop in Clyde Street”.93 Not only did he need to secure funds, he had to find a larger building, fit it out with games, furniture, and refreshments, secure the volunteers to run it and provide entertainment and music. By August of 1942, Holloway had opened a two-story Red Shield Club for troops “at the eastern end of the traffic bridge”.94 It was stated, “Adjutant Holloway, whose artistic ability is seen to advantage at the front of the building, already has the Red Shield Club in full operation.”95 His artistic skills were also used for the military soldiers of Kempsey. As men left for war, they were given a pocket wallet with the inscription, “Above all, be a Christian soldier, and may God bless you and bring you back safe and well in every way”. These wallets were inscribed by Holloway, this showed his versatile artistic skills. 96 His leadership in organising The Salvation Army’s war work saw him appointed full time into the Red Shield War Services of The Salvation Army.

War service with The Salvation Army

In January 1943, Adjutant G. Holloway was appointed to assist at Red Shield Headquarters in Brisbane, for The Salvation Army’s Military work. 97 As much of Holloway’s work would have needed to be kept out of the media, information on his movements were therefore difficult to locate. On Tuesday 29 June 1943, Brisbane City Temple hosted an event to raise funds for The Salvation Army’s war effort, titled “Special Red Shield Night.” It was advertised as a “Programme of Music and Sketches by Major H. Woodland and Adjutant F. G. Holloway, assisted by City Temple Band.”98 In October of that year, Holloway was again on the move; he was appointed to take charge of The Salvation Army’s work in the Sellheim Camp in north Qld, near Charters Towers.99 The Ipswich newspaper, The Queensland times announced that,

Word has been received from the Red Shield Headquarters …. Of the release of No. 2 Ipswich mobile civil canteen unit, to be used by Adjutant Geo. Holloway as a military unit to service troops in a northern area. Word is to hand that the Adjutant and the canteen have arrived safely at their destination. The canteen will be of great service at the Red Shield post.100

No information could be found on Holloway’s movements throughout 1944 and no notes appeared about any transfers. However, by January 1945, it appeared that Holloway had been reassigned to a Military camp near Beaudesert, Qld, a rural town about 70 km south of Brisbane. He requested volunteers to join the “Red Shield Sewing Club” in the Beaudesert area. This had been a group of volunteers who visited Military camps each week to sew for the troops.101

92 “Red Shield Club”, The Macleay argus, (Kempsey, Friday 10 July 1942), 5. 93 “Red Shield Club”, The Macleay argus, (Kempsey, Friday 7 August 1942), 5. 94 “Red Shield Club”, The Macleay argus, (Kempsey, Friday 7 August 1942), 5. 95 “Red Shield Clubs”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 19 September 1942), 6. 96 “On service”, The Macleay argus, (Kempsey, Friday 30 October 1942), 2. 97 “Red Shield doings”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 13 February 1943), 4.; “Town topics”, The Macleay argus, (Kempsey, Wednesday 6 January 1943), 2. 98 “Salvation Army”, The telegraph, (Brisbane, Saturday 26 June 1943), 4. 99 “Personal intelligence”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 9 October 1943), 5. 100 “Red Shield Huts”, The Queensland times, (Ipswich, Saturday 2 October 1943), 3. 101 “Red Shield Sewing Club”, The Beaudesert times, (Qld, Friday 12 January 1945), 2.

‘Brother’ Holloway

Sources on Holloway again went cold throughout the remainder of 1945; no information appears on him in The war cry or newspapers until he appeared in a report on the Parramatta Corps late in 1946. The sources from this point on also failed to give information on his wife or any children, although some personal memories state there was a daughter with him at Bankstown Corps. Also, none of the reports in The war cry gave a rank, they only listed, “Brother Holloway”, which appears to show he had left officership. There are also some conflicting information in sources about his links with The Salvation Army. There is no clear indication what employment Holloway had once he left officership; he may have returned to his earlier signwriting trade as he was soon using his painting talents as an evangelical tool in The Salvation Army and a War cry item encouraged people to use Holloway’s artistic talents. 102 Holloway appeared in November 1946 at Parramatta Corps, NSW. One Sunday, “[i]n the afternoon Brother Holloway’s lightning sketches, illustrating various songs, and his narration of The Prodigal Son, with accompanying sketch, were effective.”103 At this time it appears Holloway was living at East Bankstown. This suburb was listed in an 1948 issue of The war cry, although no other information was given about him, except a picture of a poster he had illustrated.104

An example of artwork by George Holloway, 1948105

Although no longer an officer of The Salvation Army, Holloway’s zeal for souls had not wavered and the use of his talents still led people to God. Although Holloway had left officership, he had remained a soldier of The Salvation Army and was to continue to use his artistic gifts. There appeared to be several themes of meetings in which he used his sketches and painted illustrations; meetings for young people, revivals to awake and grow spiritual awareness, and fund-raising activities.

102 “‘Not by might, nor by power’”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 3 July 1948), 8. 103 “Eighteen at Parramatta”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 30 November 1946), 6. 104 “‘Not by might, nor by power’”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 3 July 1948), 8. 105 “‘Not by might, nor by power’”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 3 July 1948), 8.

Young people’s meetings

A few reports showed that Holloway could effectively minister to children and young people. In 1948, at the Belmore Corps’ Young People’s Annual, Holloway “sketched his illustrations of spiritual truths”.106 In 1950, he participated in the youth weekend at Bankstown Corps with his “lightning sketches”.107 In 1951, Holloway, with the support of Bandsman Bryon, led the Sunday meeting for the young people’s anniversary at Willoughby Corps. It was stated, “Brother Holloway, a talented artist, held the attention of tinies and adults by his lightning sketches with which he illustrated his lesson.”108

Revival meetings

Holloway’s desire to teach people biblical truths and see them convert to Christianity remained strong. In 1949, on a Sunday afternoon at Sydney Congress Hall, “Brother George Holloway gave a spiritual message illustrated by lightning sketches.”109 Then, later in the year at Marrickville Corps, “[t]wo reconsecrations were made at Marrickville on Sunday night, when Brother Holloway gave the lesson with brush and paint.”110 In 1951, there were a few events aimed to develop spiritual awareness of Salvationists and non-Salvationists alike. Firstly, Holloway’s skills were used to introduce how Salvation Army cadets received their calling to officership,

Brother S. [sic] Holloway enlivened the afternoon Meeting with his lightning sketches, illustrating how Christ entered the life of the Cadets, as each gave their testimony. Two boys sought Christ.111

Secondly, at Ashfield Corps, “Special Meetings have been conducted by Mrs. Lieut.-Colonel R. McClure, Lieut.-Colonel Robert Rignold and Brother George Holloway.”112 Thirdly, a report on Parramatta Corps stated, “Brother George Holloway, the lightning sketch artist, led a profitable Sunday night Meeting.”113 Fourthly, “artist George Holloway” joined with “well-known Pastor of the ‘Church in the Wildwood’ Session [on] 2CH [radio]” at Sydney Congress Hall in 1954.114 Even while on holidays, Holloway would attend The Salvation Army and assist in meetings. In 1953, he visited Nowra, where he had previously been the corps officer. When visiting the corps, he “gave an illustrated address”.115 At his local corps he also used his talents to teach the community about Christ. At Bankstown Corps, Holloway would often do “roadside sketch lessons” at open-air meetings.116

106 “Infectious Christianity”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 17 January 1948), 7. 107 “Young people to the fore”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 5 August 1950), 7. 108 “Youth activity”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 30 June 1951), 7. 109 “Sydney Congress Hall”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 23 April 1949), 6. 110 “Training College newsletter”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 24 September 1949), 6. 111 “Illustrated testimonies”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 9 June 1951), 6. 112 “Ashfield”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 11 August 1951), 6. 113 “Three girls and a man converted”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 25 August 1951), 6. 114 “Advertising”, The Sydney morning herald, (NSW, Saturday 19 June 1954), 21. 115 “Visitors help”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 14 March 1953), 7. 116 “Busy at Bankstown”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 2 July 1955), 4.

An example of a Bible truth lighting sketch drawn by George Holloway titled “Life’s voyage”. There is evidence that this talk was given at both Waverly Corps and North Sydney Corps in 1932117

117 Autograph book of Captain Edward Merrick, housed in The Salvation Army Australia Museum, Sydney, cited in “Sketches from an autograph book”, 7 – 9.; Callaghan, “A recent arrival at the museum”, 7 – 8.; “Waverly”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 6 August 1932), 12.; “Daffodil fair”, The war cry, (Sydney, Saturday 3 September 1932), 13.

Fund raising activities

The Salvation Army had many opportunities for people to attend events to raise finances for corps and social work. In 1952, “Brother F. G. Holloway conducted the Sunday Meetings”, for the Harvest Festival at Daceyville Corps, with the Belmore Corps band and songsters assisting.118 In 1953, he conducted the “Harvest Sunday meetings” at Mortdale Corps and it was said of him that his “sketching brought gospel truths to life”.119 Later in the year, Holloway did a similar presentation at Manly Corps, as “Harvest Festival meetings were conducted by Brother George Holloway of Bankstown, whose illustrative paintings created great interest both at indoor and open-air meetings.”120 Holloway also painted cars. In 1953, Salvationists throughout Australia raised funds to supply a motor vehicle for Senior-Captain Gladys Callis in Indonesia. Holloway gave his time and paint free for the signwriting on the vehicle before it was shipped to Callis.121 The Salvation Army has placed a great deal of importance on the annual collection of the SelfDenial Appeal; a way of raising funds for the movement’s work. In 1956, a meeting was held at Sydney Congress Hall to celebrate the amounts of money collected by individuals and Salvation Army departments. As each total was announced, Holloway and another Salvationist artist, A. Stuart Peterson drew cartoons,

Under the title, “The eyes have it,” artists A. Stuart Peterson, of Congress Hall, and George Holloway, of Bankstown, kept the crowd highly interested with their cartoons portraying the totals raised by the various departments and divisions.122

Personal life and Sydney’s northern beaches

After Holloway left officership there were still times of grief. Holloway’s father, Frederick William Holloway passed away in 1953; and the remaining son, John Garth Holloway was promoted to Glory on 5 November 1955 at Hurstville (he had been born in Kempsey on 6 June 1942). 123 Tracking Holloway’s movements, it appears that he lived in the Bankstown area until about 1957/1958 when his circle of travel changed to centre around Salvation Army corps in the northern beaches of Sydney. Holloway’s relocation to the northern beaches of Sydney was to some extent a homecoming, as it was from this area, he went to The Salvation Army Officer Training College in 1930. The move did not stop his ministry. Holloway joined the Dee Why Corps and participated in the brass band and other ministries. One of the first major events Holloway was involved in was a weekend to celebrate the history of the corps. The weekend “was arranged by local district historian and C.S.M., Chas McDonald, and artist, Bandsman G. Holloway.”124

118 The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 22 March 1952), 7. 119 “Won by swearing-in”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 28 March 1953), 7. 120 “Youth progress”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 18 April 1953), 7. 121 “Jeep for Indonesia”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 14 February 1953), 5. 122 “Causes rejoicing in Eastern Territory”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 27 October 1956), 4. 123 NSW, birth, deaths, and marriages, https://familyhistory.bdm.nsw.gov.au/lifelink/familyhistory/search/result?22, retrieved 12 February 2021.; ancestry.com.au; https://www.ancestry.co.uk/discoveryui-content/view/1413622:60528 accessed 19 February 2021. 124 “Past and present”, The musician, (Australia, September 1957), 132.

Dee Why Corps brass band showing Holloway on cornet125

In 1958, Holloway conducted campaigns throughout the former Australia Southern Territory with other Salvationists from the Sydney area. These campaigns were designed to encourage people to attend The Salvation Army. Firstly, in March, Holloway travelled to South Australia where the Adelaide Congress Hall band assisted him with a program.126 Secondly, in June, he travelled with other Salvationists to Victoria, the advertisement of their visit stated,

Young People’s Sergeant-Major (Dr.) and Mrs. W. Kinder and Brother G. Holloway, all of Sydney, are to visit Melbourne for the Queen’s birthday holiday weekend. Brother Holloway, a lightning sketch artist, illustrates band and songster numbers, and the visitors will take part in festivals at Camberwell (Friday), Malvern (Saturday) and the Melbourne City Temple (Monday).127

Only the reports of Holloway’s time in Camberwell and Melbourne City Temple could be located, yet these gave positive feedback of the events. 128 Later in the year, Holloway collaborated again with “the well-known radio personality, Mr. John Davis,” to “illustrate with rapid sketching” Davis’ talk. The presentation was given at The Salvation Army Petersham Corps, Sydney. 129 One weekend in 1959, Holloway, again with YPSM Dr. Kingston Kinder, travelled to the south coast of NSW to conduct a meeting for the Woonona Salvation Army Corps. It was stated that while “the doctor [was] giving the address, [it] was skilfully illustrated on the sketch board by Brother Holloway.”130 To commemorate the life and work of Australian poet Henry Lawson, Holloway travelled to Grenfell to paint a mural depicting Lawson’s poem, When the Army prays for Watty. The painting was placed in the window of the grocery store owned by fellow Salvationist Bandmaster Jack Stiff. 131

125 “21 years at a seaside corps”, The musician, (Australia, 21 July 1962), 112. 126 “Additional effort”, The musician, (Australia, March 1958), 42. 127 “Paragraphs of interest”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 21 June 1958), 4. 128 See report of the event, “Youthful seekers”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 2 August 1958), 7.; “Extracts from a Staff Bandsman’s diary”, The musician, (Australia, August 1958), 124. 129 “Seekers a stimulus”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 4 October 1958), 7. 130 “Visit by T.Y.P.S.” The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 18 July 1959), 6. 131 “Impressions of an artist and a poet”, The musician, (Australia, September 1959), 143.

A mural painted by George Holloway depicting When the Army prays for Watty. It was placed in Bandmaster Jack Stiff’s grocery store for “Henry Lawson celebrations at Grenfell”132

132 “Impressions of an artist and a poet”, The musician, (Australia, September 1959), 143.

Holloway became very active in the Dee Why Corps. Before the opening of their new hall, the Dee Why Corps were holding salvation meetings each Sunday night at the local camping ground. One report on these activities showed the attraction that artistic forms had on children. The war cry report stated,

One woman has asked for the names of her children to be put on the roll at Ryde where they live. These young people have been particularly interested by Brother G. Holloway with his sketches, Bandsman (Dr.) Kinder with the flannelgraph and Mrs. Major H. Hill with puppets.133

As with his time as a Salvation Army officer in Brisbane, Holloway was again used for large Salvation Army events. A territorial young people’s musical festival was held at Sydney Congress Hall and included items from young people representing four different divisions. At the event, “[t]he Deewhy [sic] young people presented the 23rd Psalm while Brother G. Holloway was illustrating with sketches”.134 On 14 October 1961, the Dee Why Corps opened their new citadel and young people’s hall. 135 The painting of the text on the wall behind the platform was done for the opening by Holloway. It is a clear example of Holloway’s work. The Dee Why Citadel painting is also a good example of the quality of his work, as only after many years was it needed to be touched up. It was appropriate that Holloway’s friend, Mrs Beryl Kinder later enhanced the colours of the painting to return it to its original condition. At this point, the painting in the Dee Why Corps Citadel appears to be the only remaining example of Holloway’s work on the wall of a Salvation Army building still in existence. Also, as much of his work was painted for one off events, there appears to be little of his work available for viewing. While Holloway attended the Dee Why Corps, he assisted the Newcastle Corps with a float for the ‘Mattara Festival’ with great effect. The war cry report stated, “Brother George Holloway, of Dee-why [sic], supplied the luminous paint signs and the Army float secured second place in the religious entries.”136 In 1962, Holloway helped with another large Salvation Army young people’s event, the children’s meeting at a Territorial Congress. The report of the event stated,

On Sunday afternoon 200 children attended a young people’s company meeting held in the basement of the Sydney Town Hall, under the direction of Major T. Higgins and Major J. McCabe with divisional youth officers assisting. Brother George Holloway assisted with lightning sketches.137

By the mid-1960s, Holloway had transferred to the Manly Corps. Manly Citadel gives another example of Holloway’s work in Salvation Army halls. In this citadel is possibly the only example of his work on a wooden framed board. It is more difficult to identify other paintings done by Holloway as there are few records of his work. The text identified by Captain Louanne Mitchel at the Manly Citadel shows a similar style to that of the Dee Why Citadel, however not directly painted on the wall, but rather on a board and in a frame.

133 “DeeWhy [sic]”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 19 March 1960), 7. 134 “Annual festival”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 24 September 1960), 5. 135 “Imposing set of corps buildings dedicated and opened at Deewhy [sic]”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 28 October 1961), 4. 136 “Army float attracts attention in Newcastle procession”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 28 October 1961), 4. 137 “Night of prayer”, The war cry, (Melbourne, The Easter, 1962), 11.

The text believed to be painted by George Holloway, Manly Corps138

There is something of a strange source in the life and ministry of Holloway. Captain Louanne Mitchel, the current Corps Officer of the Manly Corps stated that the corps history book records that on 12 April 1966, in the Manly Corps Citadel, the hall from which he left for College 36 years previously, George Holloway was re-enrolled as a senior soldier of The Salvation Army by Captain Ron Whitehouse. It was said that he and his wife attended the corps for a number of years.139 However, Holloway was clearly a soldier in Dee Why throughout the 1950s and assisted in evangelical campaigns. There could be an error in the written statement in the history book or the meaning may have been that the Holloways transferred into the corps or renewed their covenant at this time. During Easter 1966, Holloway presented his lightning sketch at the events held at Dulwich Hill Temple Corps which “attracted an overflow crowd”. The report continued,

Lightning sketch artist Brother George Holloway painted scenes of the garden, the trial, the crucifixion and the resurrection, whilst appropriate music was presented by the temple band and songster brigade and individual singers. A personality attraction of the night was Bruce Menzies, of TV Channel 9, as narrator, with script written by Major Nelson Dunster.140

This was the final report located on Holloway’s artistic gifts used in meetings. As technologies changed, visual images became mass produced and easier to obtain, and fewer varieties of talks were given in meetings, Holloway disappeared from War cry reports linked to meetings. Four years later, in 1970, Holloway painted a mural and presented it to the Manly Corps. It appeared to be a painting of Jesus at the wheel of a vessel during a storm. The final statement on Holloway was that in 1972 he travelled to Toowoomba. Of interest was that Holloway’s brother William Henry Holloway had died in Toowoomba at an earlier date, so George Holloway may have gone to visit family. Additionally, Frank Shaw was listed in the report, showing that Holloway and his old mentor still had contact. 141

138 Photograph courtesy of Captain Louanne Mitchel. 139 Information supplied by Captain Louanne Mitchel. 140 “Final Easter news reports”, The musician, (Australia, 28 May 1966), 80. 141 “Shield winners”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 18 November 1972), 5.

It appears that at some time after 1972, Frederick George Holloway moved to New Zealand and was promoted to Glory from there in 1999. Dorothy, his wife is believed to have died in 2005, although the location has not been identified. 142 Sadly, there has been no tribute to Holloway located. But it is certain that his brushstrokes reached people; the people that only paint and pictures could. His tribute lies not in written text, but in the souls of those he reached with the Gospel. It is clear that Holloway was a talented artist and appeared at the time where the visual image was becoming more important to portray messages. Referring back to the quotation at the beginning of the paper, William Booth encouraged Salvationists to consecrate their artistic gifts and this was evident in the life and art of Holloway.

George Holloway aids in the unveiling of his mural at Manly Citadel, 1970143

142 Ancestry.com.au. 143 “Mural at Manly”, The war cry, (Melbourne, Saturday 30 May 1970), 3.

Photograph of Salvation Army officer, Adjutant Harry Munn; known as ‘Mad Munn’1

1 Photograph originally owned by Robert and Phyllida Munn. Courtesy of the author.

Richard Munn

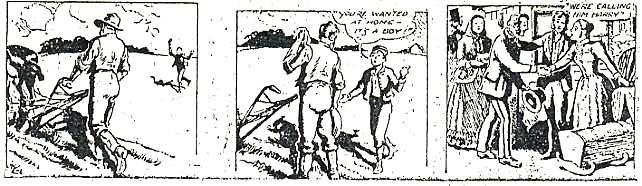

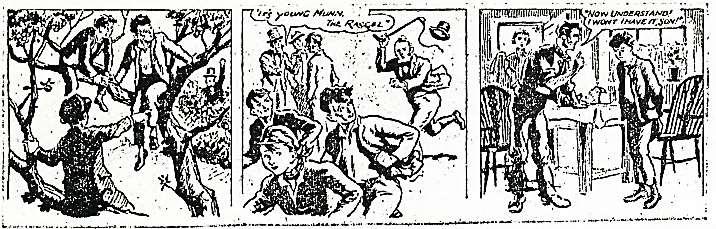

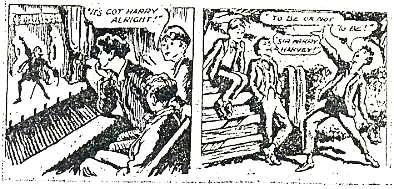

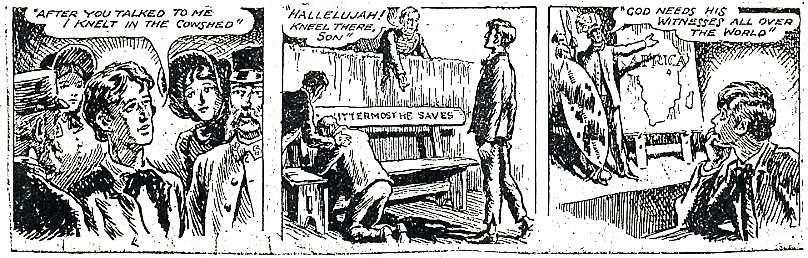

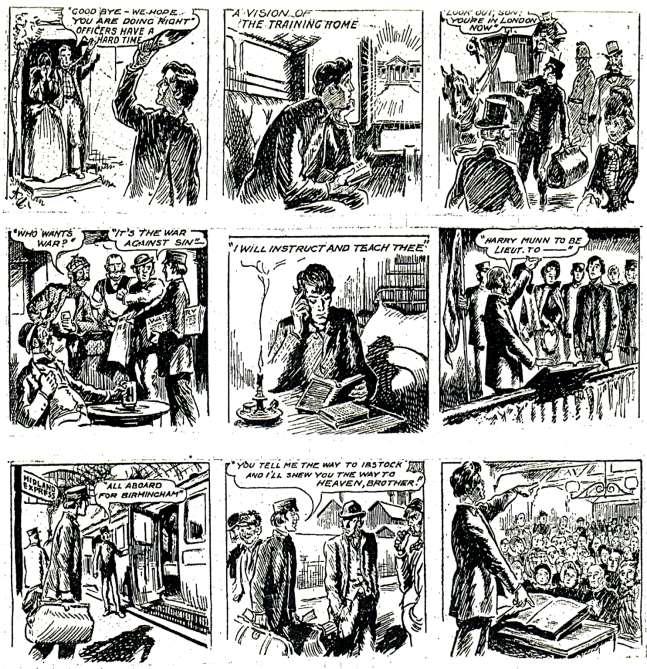

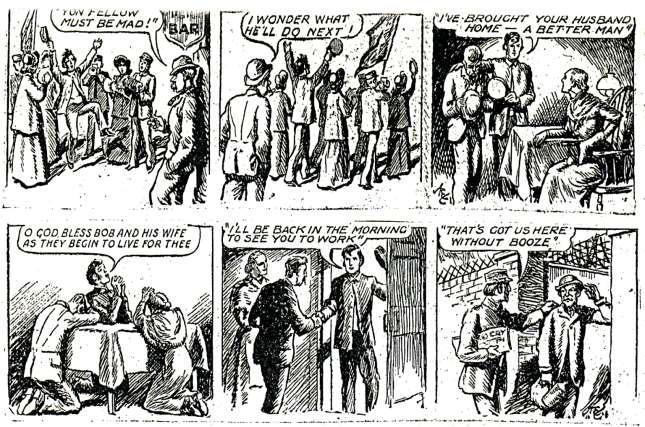

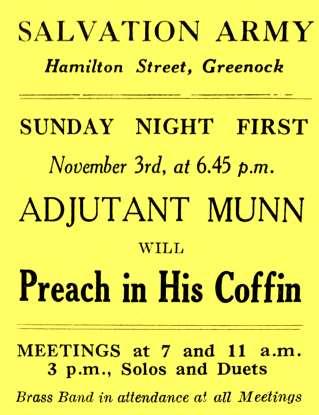

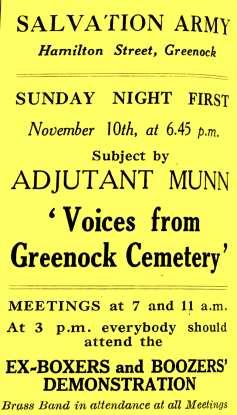

Harry Munn (1864 – 1904), aka ‘Mad Munn’ was imprinted upon me from early childhood by a unique combination of revered awe and tongue-in-cheek mischief, “your great grandfather was known as ‘Mad Munn’ you know, he used to preach from a coffin.” Adding to the mystique, his notably large and framed Victorian photographic portrait hung prominently in the living room of the south east London Salvation Army home of my grandmother Dora, wife of Mad Munn’s son, Harry. He always seemed to be surveying us all as we visited, keeping a hawkeyed review of our exploits for Army mission.2 Then, with exquisite timing for this imaginative boy, the UK War cry embarked on a weekly cartoon series in the early 1960s, Alive in his coffin– retelling in picturesque and bite-size episodes the life story of Adjutant Harry Munn.

Alive in his coffin ‘Mad Munn’ by A.E Horne and Albert Kenyon3

Reference citation of this paper; Richard Munn, “‘Mad Munn’ – Arising again. A great-grandson recalls the theatrical evangelist”, The Australasian journal of Salvation Army history, 6, 1, 2021, 121 – 135.

2 See “Photograph of Salvation Army officer, Harry Munn; known as ‘Mad Munn’” . 3 Images are from A.E Horne and Albert Kenyon, Alive in his coffin ‘Mad Munn’, in various issues of The war cry, (London, 1963). Some strips also appeared in various issues of The war cry, (Melbourne, 1952).

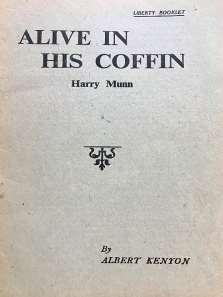

The narrative outlined in The war cry serial was originally described in the same-named booklet by Albert Kenyon. 4 Kenyon’s booklet was part of the Liberty Booklet series of Salvation Army great hearts such as William and Catherine Booth, Kate Lee, and James Dowdle; first printed and produced during the 1940s.

4 Albert Kenyon, Alive in his coffin – Harry Munn, Liberty Booklet, (London, UK: Campfield Press, Salvationist Publishing Supplies, 1948).

Cover of Liberty Booklet, Alive in his coffin5

Alive in his coffin listed with other biographies of well-known Salvationists in the Liberty Series6

Imagine that?! My very own ancestor featured in a weekly cartoon and had a biography in a collection featuring the Founder! It just added to the aura. Finally, for extra flourish and emphasis, on a dark January Sunday evening Salvation Meeting in 1970, this earnest 14-year-old was enrolled under the army tricolor by the visiting divisional commander, who promptly informed the gathered uniform-wearing Letchworth Corps, United Kingdom, that I came from “the greatest evangelist in the history of the Army. ” Even I knew that had to be an exaggeration, that Booth and Railton might have greater credentials in that regard. But, it was yet another stamp of imprint.

5 Kenyon, Alive in his coffin, front cover. 6 Gladys Moon, Conquistador – Eduardo Palaci, Liberty Booklet, (London, UK: Salvationist Publishing and Supplies, 1946), back cover.

As the years have rolled by, and thanks to the wizardry of digital filing and publication, I have been able to gather together some of the details and narrative of this evidently larger-than-life personality. In so doing I have been inspired at the flaming, flamboyant evangelistic energy, and simultaneously convicted at the overflowing heartfelt love and compassion for ‘the lost’ displayed by Harry Munn.

Childhood and Conversion

Harry Munn was born in 1864 in the hamlet of Hoo, Kent, in the very southeast of England.7 The religious or Christian commitment of the family of origin is undetermined, though described as “respectable non-conformist” . 8 What seems apparent is that Munn had a flair for the dramatic and was gripped by the visiting actors of a touring theatre, maybe in the kind of fore-runner magical moment that prepares for future energies.9 All this converged when The Salvation Army came to town in 1885. 10 Munn was saved as a young person, and we read, sensed the calling of God for officership. His theatrical temperament had found the perfect channel for full expression.11

Officership

Following a short training experience in Clapton, London, Munn was released like an evangelical bird to exert his considerable imagination, dare and youthful energies for evangelism. Soon after commissioning he met fellow officer Lucy Phillips, and they were married, an event which was somewhat romantically, even imaginatively, recounted by Albert Kenyon. 12 What can be recorded with some confidence is that Lucy also came from an active and pioneering Army family, with her brother W. Raglan Phillips founding The Salvation Army in Jamaica.13

Munn’s corps appointments included outer Birmingham in England,14 Govan in Scotland,15 and Belfast in Northern Ireland.16 While at Govan there were a few references to his evangelical skills. Kenyon wrote,

In fourteen days 130 people had sought God at the Govan Penitent Form; and during the eleven months the Munns were there no fewer than 5,000 seekers were registered.17

What Kenyon did not write was that Munn helped to rescue Govan Corps. The official history of the Govan Corps showed that after the corps had been in operation for 18 years divisional headquaters