7 minute read

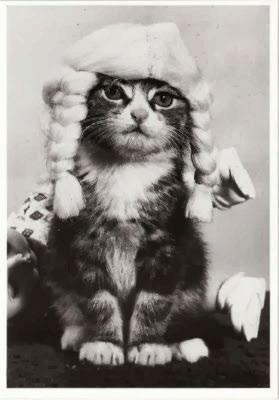

Cats in the Courtroom: the problem of a fickle judiciary

Next Article

by Joe Davies

Those of us familiar with the courtroom drama may think of judges as a sort of trial referee: a stern yet sympathetic authority figure whose sole purpose it is to say ‘hmm…I’ll allow it this once’ with an eyebrow arched in curiosity as the prosecution commits some of the most heinous violations of legal protocol you’ve ever seen (they really did Get Away With Murder in that show). While to some extent this is true (a story all in itself, believe me), judges serve a much more significant, if often overlooked, purpose in the trial process.

The prosecution presses particular charges against the defendant on behalf of the crown; the jury decides whether or not the defendant is guilty of the crime; and if they’re found guilty, the judge decides the sentence the defendant has to serve. This power, however, is pretty contentious. In a system founded on checks and balances, sharing power between the people and the state, establishing a paragon of justice, it’s a little odd that once they’re found guilty, one guy has the power to decide whether they go to jail for 6 months or 6 years. Since judges have unilateral power, within the bounds of statute/precedent limitations, to decide the severity of a sentence – including, in several jurisdictions across the world, the death sentence – the question then becomes: can judges be trusted not to be subjective or arbitrary when passing judgement? And if not, what can be done to overcome this?

This idea is often raised in the context of the question, ‘does it matter what a judge had for lunch?’: the idea being, if the judge had a particularly satisfying lunch, would they be more inclined to give a more lenient sentence and vice versa? Where sentences aren’t mandatory and are instead left to judicial discretion, there is a natural risk that the personal biases of a judge, however slight, may affect their sentencing decisions. But is this a valid concern?

There is a strong argument to suggest that, even with the power a judge has over sentencing, the feelings of the individual ultimately have very little bearing on the eventual sentence due to the system of legal safeguards that constrain this ‘unilateral’ power. The first of these is the sentencing limits: most crimes will carry a minimum and/or maximum sentence, which provides a range in which the judge can operate at their discretion. This, in theory, prevents two convicts from receiving wildly different sentences for the same crime, with judges considering circumstantial factors to make adjustments where necessary. Therefore, even if a judge’s impartiality may be compromised by personal factors, the consequences of this should not be excessively significant because the outcome is essentially the same. Furthermore, judges have the option to remove themselves from the trial if they recognise their impartiality may be compromised. This process, known as judicial recusal, exists to check the legal power of a judge’s opinion by giving them the option to withdraw from a case they may compromise, and, since judges are renowned for their legal wherewithal, they will more often than not opt to recuse if they suspect they may unfairly influence sentencing. Although some may argue that, since recusal is a personal choice, there is no guarantee that a judge will go through with it, lawyers have the ability to request recusal if they believe a judge is not in a position to make an unbiased ruling. If this is found to be correct, the judge is now expected to recuse themselves, and failing that, the lawyer can file a higher court appeal for judicial disqualification which takes the matter out of the judge’s hands. On the subject of appeal, a judge’s ruling is not necessarily final. If the defense believes a conviction or sentence to be unjust, they have the option to appeal the case through to the higher courts. Ultimately, unless the defendant has some astonishingly bad luck, they will at some point receive an uncompromised second opinion that does its due diligence in trial, maintaining the objectivity required for our system to function. The legal system recognizes the authority of the judge in sentencing, but it is also aware that judges are only human too. It is not oblivious to the ramifications of this level of unilateral control if left unchecked, and so the aforementioned safeguards hypothetically prevent this authority from contravening the justice it sets out to protect.

However, regardless of what the legal system ‘sets out’ to achieve, does this system actually work in practice? Can something as simple as a dodgy lunch really compromise the broader integrity of justice? Despite the steps taken to minimize the possibility of unfair trial through non-legal factors, the system is far from perfect. Firstly, the range of minimum to maximum sentences can vary wildly and depend largely on non-empirical value judgements. Looking at shoplifting as an example, where stealing over £200 worth of goods can carry a maximum sentence of seven years in custody, it depends on whether or not the judge believes the defendant to be ‘capable of rehabilitation’ that decides if they experience jail time. The consequences of imprisonment relative to a non-custodial penalty are unjustly disproportionate, with severe and long-term impacts on social, physical and psychological wellbeing, and the difference between one or the other is solely how charitable a judge is feeling on a certain day. This, too, is where the problem lies with existing safeguards: it underestimates how powerful the most minor of influences can be.

Judicial recusal most commonly applies to severe, and most importantly obvious, conflicts of interest, largely pertaining to personal involvement or ideological biases. These are blatant, quantifiable and easily resolved IN THEORY. In reality, the prejudices of a judge may be much harder to prove, harder still to force recusal, and that still doesn’t account for the possibility of a judge, on average a sixty-year-old upper middle-class man, forming a dislike of someone who wears a crop top or septum piercing to court. Even that may be too generous: with the power judges wield over the legal system, even blatant abuses of the system over serious prejudice often go unpunished.

Judge Les Hayes once sentenced a single mother to 496 days behind bars for failing to pay traffic tickets. The sentence was so stiff it exceeded the jail time Alabama allows for negligent homicide.

As mentioned previously, the ‘essentially negligible’ differences between sentences are not so negligible to the lives they impact – an extra year in jail means little on paper, but everything in practice in terms – so both the random and systemic biases of a judge in determining where they fall on the sentencing spectrum expose defendants to massive, undue risk. This also fails to address the strain on the defendant throughout this process: appeals are not a guarantee, especially when the influencing factor is so insignificant that it is entirely overlooked, and even if one is granted, it takes up valuable time and resources to achieve a ruling that should have been given in the first place. There’s a domino effect at work here, where the smallest factors can snowball into cataclysmic disasters, and the legal system fails to account for such possibilities.

However, the most dangerous possible consequence of judicial indiscretion is embedded into the very fabric of British law, and could be disastrous if left unaddressed.

The UK, like many anglophonic countries, operates under a common law system. Unlike civil law, where case rulings are largely determined by legislature, common law depends on case precedent: that is, a judge’s ruling has the potential to influence how future cases of similar circumstances will be settled. Herein lies the problem: a questionable decision made by a judge on a certain day in a certain situation goes on to shape how all future cases in that vein will be settled. The power of judges to shape the fabric of the law through their decisions is not a responsibility taken lightly, but this unilateral authority is still dangerously susceptible to human subjectivity, and the more ingrained these rulings become in our legal system, the more difficult they are to extract. When a soggy egg-and-cress sandwich has the capacity to determine that every shoplifter from a lowincome community is sentenced to seven years in prison, no matter how unlikely it may seem, it is a sign that serious initiative needs to be taken to eliminate even the possibility of such an outcome.

The question then becomes, when confronted with the problems of an arbitrary judiciary, what can be done to fix it? The first potential solution, to have a fixed sentence for a crime substantiated by quantifiable factors, e.g. the value of goods stolen, has its merits in that it eliminates the possibility of injustice on a case by case basis. between cases, it seriously undermines fairness within cases. The second potential solution, to have a panel of multiple judges collaborate on a ruling, carries greater promise: the immediate introduction of a second opinion separate from the appeals process would save resources and guarantee a greater element of impartiality. However, this system would only occupy more immediate resources where they may not be required, and while a collection of different opinions could nullify potential bias, the equal likelihood that two similar opinions collide could only exacerbate the initial problem. A ‘good judge, bad judge’ setup, though seemingly taken from a lost Gilbert and Sullivan musical skit, increases the odds of an impartial ruling, but the defendant facing trial after a canteen catastrophe stands little chance. The significance of the judge in our justice system can be our greatest strength, but it has the potential to be our greatest downfall, and with the system as it is, that human element is impossible to compensate for.

Judges are the foundation of British law. Their expertise, their fair judgement and their uncompromising commitment to the law make them the indispensable glue that binds the system together, ensuring that, no matter the ruling, trials remain free, fair and factual. However, judges are also only human, with human problems and biases. These human problems colliding with the required objectivity of law is a recipe for disaster, with potentially severe and lasting consequences. And yet, without the human element, if we were all exposed to the unfeeling monolith of Law, would we be any better off? Ultimately, judges are arbitrary by nature of their humanity, but how we seek to resolve this without compromising the fundamental humanism of our legal system is a challenge that will take a great deal of examination, understanding and patience to resolve.