5 minute read

Community resolution to rural housing woes

WORDS JANE CRAIGIE

Amy lives on Jura, a Hebridean island off the west coast of

Scotland. She encapsulates the endemic challenges that young, rural people have - finding a house to live in, juggling multiple jobs to make a living and needing a car to get anywhere. Like many under-30s, she left home to study and decided to return home to live her life. To do so, she says, she needs to be resourceful and needs the support of her strong, local community.

Without young people, their energy, sense of can do and their perspective on a better, more environmentally conscious future, our rural communities will struggle to survive. If our young people leave, we lose both local services and the sense of community that you see with strong intergenerational places.

One of the biggest challenges for young, rural dwellers is the lack of affordable, or ‘decent’ housing. Amy lives with her partner in a static caravan on her parent’s croft.

Many of the available properties in the UK countryside are large, expensive to rent and to heat. In popular tourist areas, like Cornwall, the availability problem is exacerbated because so many properties are holiday lets. The post-pandemic desire to flee the cities to the countryside, or coast, has compounded the problem, with frequent stories of ‘outsiders’ paying a year’s rent upfront to secure a ‘getaway’ property somewhere rural and beautiful.

The UK isn’t alone. In Canada, Reuters reported that, in some communities – triggered by Covid - house prices jumped more than 75% in one year. The migration to rural places is locking local people – particularly the young – out of the housing market.

So how are rural communities and policymakers tackling the endemic challenges - the lack of sufficient quantity, quality, or suitable properties for local, rural dwellers of all ages? And how can the investment also support the community’s income-generation, particularly young people without the capital to start their own business?

Tread ISSUE 2 COMMUNITIES WITH PURPOSE

Finland and South Korea are two countries which put community and self-help at the heart of planning infrastructure and services. Arguably, they paint a picture of what the future of rural communities could look like - shared wealth and prosperity and communities that care – in particular - for their young and their old.

In South Korea, the Government had spearheaded ‘sustainable’ investment into these communities, all focused on wellbeing – healthy communities, healthy food and self-help.

One village had built a community kitchen and supermarket, where local growers and small-scale manufacturers could make, pack, and sell their foods. The facility gave young people a way to make their living and an anchor to stay locally.

Another community is best described as a retirement village – but not an archetypal one. The houses are small and beautifully kept. The residents are all over 70. In their communal kitchen they make the traditional Korean staples of tofu and kimchi – which they sell to give the community its income. The community looks out for its own ‘folk’ and has a strong sense of purpose and reason to exist.

Finland shares a lot of similarities to South Korea. It is officially the happiest country in the world and is one of the most sparsely populated, with 50% of the population living rurally. The country has been experiencing a counter-urbanisation trend since the early 2000s. Covid has escalated this migration.

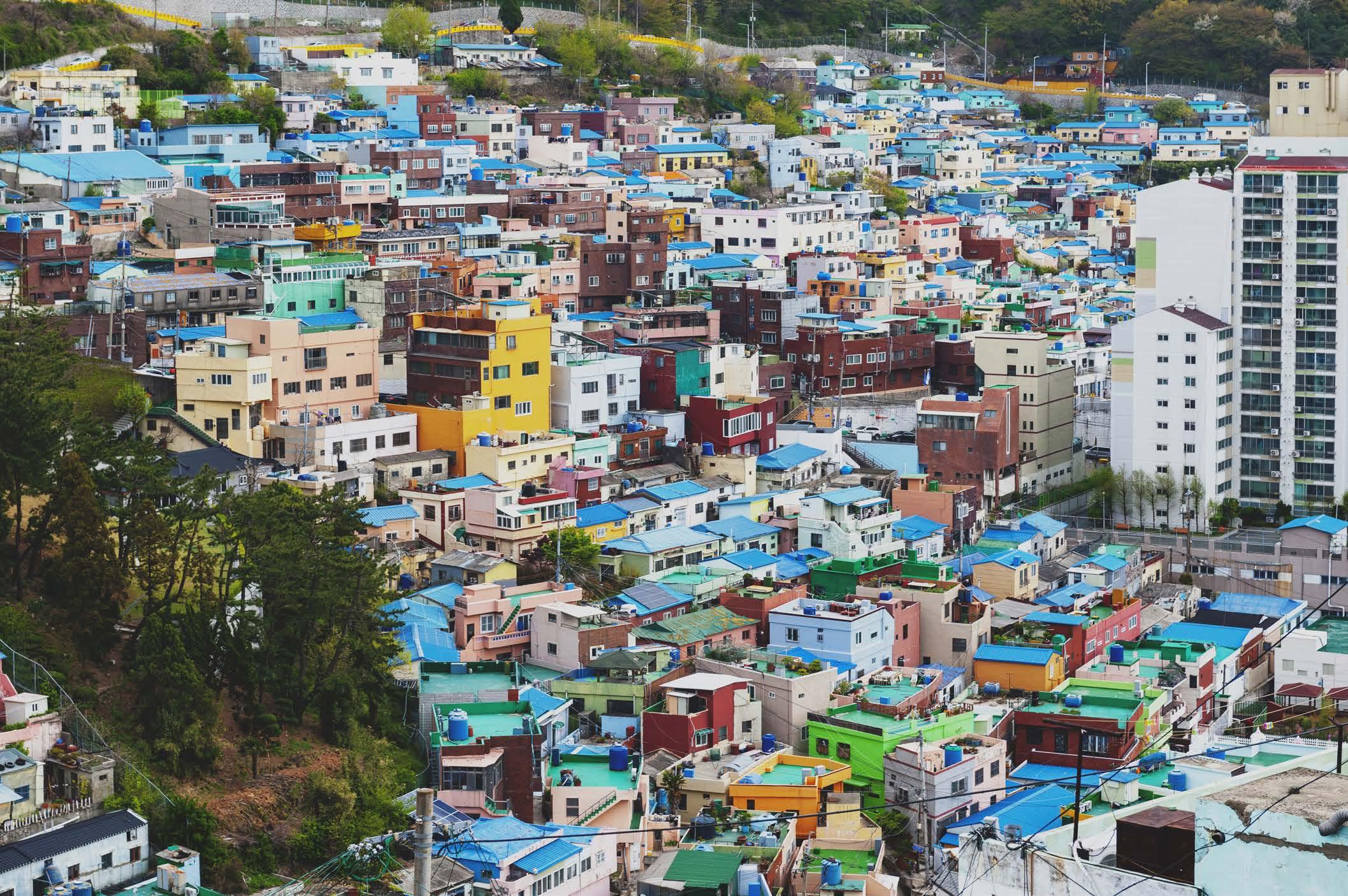

Busan, South Korea

FINNISH VILLAGE MOVEMENT

Tackling rural housing is something that the Finnish Village Movement Association (FVMA) is doing via 4,000 village development associations. Its purpose is community led local development (CLLD), community wellbeing and public participation.

The FVMA is a movement that emerged in Finland in the 1970s, encouraging people to organise at a local level. The movement focuses on small-scale, collective action over individualism. Communal facilities are prioritised or restored, as are public and social services, such as health, postal or transport services – and housing.

During the 1960s and early 1970s, Finland experienced rural depopulation. By 1974, there were first signs of a modest rural revival. The ‘counter-urbanisation’ treaded started in earnest between 2002-2009 and Covid has created another spike in a return of people to live rurally.

Kirsi Oesch, is project coordinator for the Luopionen and Kukkia villages on the shores of lake Kukkia in Southern Finland. There are 700 permanent inhabitants and over 1,000 more summer residents.

Kirsi describes these communities as having a lot of social capital, know-how and new ideas, resulting in a wave of growth in associations, social enterprises and co-ops. Covid has been a game-changer. Lots of part-time residents returned to the region – they needed housing, workspaces and services.

Luopionen and Kukkia’s communitycoordinated housing project is running from 2005-2024. Building types have been reinvented and designed by a local architect. The wooden, prefabricated units are made in Helsinki from Finland’s abundance of trees. They are as ‘eco’ as they can be, with no plastic used in manufacturing and low energy use resulting from being ‘airtight’.

Kirsi describes the principle of the design is a small house with small emissions and less ‘stuff’. The houses suit Finland’s demographics – for example, over 1 million Finns live alone – and also tap into the growing need for wellbeing. Homes planned range from just 27 m2 up to 100m2 and all have large gardens ranging from 300-500 m2 to grow vegetables and fruits. Prices start from €120k to buy and €400/month to rent. The funding for the project is from a mix of sources, private investment, EU funding (LEADER) and a local bank foundation.

The homes have shared spaces – roads, saunas and waste management. Co-working spaces have desks and audio-visual meeting rooms, hot desks cost €200 euros/year or €10 euros/day.