3 minute read

Ansel Adams & Manzanar

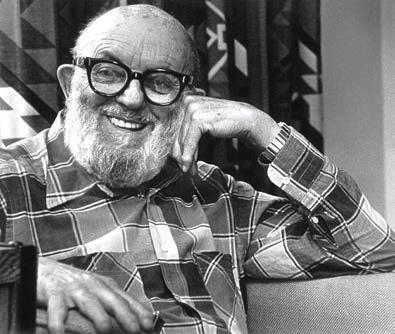

Ansel Adams in Yosemite Valley-1981, Courtesy of Thomas Kelsey.

Advertisement

With the onset of World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on March 21, 1942 evicting JapaneseAmerican men, women & children from the West Coast “for their mutual safety” and hastily placing them in 10 camps across the country-many in arid, isolated locations where they would be “protected” by the military. Manzanar, which is Spanish for “Apple Orchard” was the first camp to be established and during its first two months was known as the Owens Valley Reception Center.

Ansel Adams had expressed a desire to serve his country after he became “outraged over the deeds of the hideous Hitler regime” and was eager to enlist and make a contribution to the war effort but the married 40-year old with three dependents was turned down by the military.

He later expressed his views to an old friend from the Sierra Club, Ralph Merritt, who had been appointed Director of the Manzanar War Relocation Center who then proposed to Adams that he photograph the camp and it’s people, their daily life and their relationship to their community and the arid land near the town of Lone Pine. Adams accepted the offer to document Manzanar.

When Ansel Adams first visited Manzanar late in 1943, it had already been in existence for 18 months.

At its peak Manzanar held 10,000 incarcerated JapaneseAmericans, many from Southern California. Adams eventually visited Manzanar on four separate occasions. The images he produced in 1943-44 became the basis for his book Born Free And Equal.

“I was profoundly affected by Manzanar,” Adams later said in his autobiography. “As my work progressed, I began to grasp the problems of the relocation and the remarkable adjustment these people had made.” He was amazed at their patient acceptance of their new lives despite the fact they were behind barbed wire and in constant sight of guard towers.

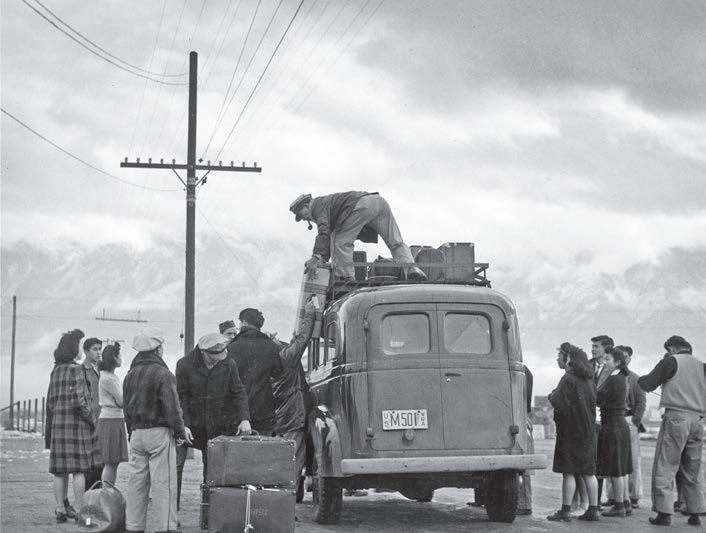

The restrictions given to Adams while at Manzanar included not being allowed to photograph barbed wire fences and the eight guard towers. All photos had to be approved by the Relocation Center’s Director Merritt. Adams focused on the people taking many portraits of the camps residents while mixing in landscapes of them working, playing and going about their daily lives, many with a backdrop of the picturesque Sierra Nevada in the background. It must be noted that

‘ Leaving Manzanar’ by Ansel Adams-1944, Courtesy Library of Congress. during his stay at Manzanar he recorded two of his most enduring images, “Winter Sunrise, Sierra Nevada from Lone Pine-1944” and “Mt. Williamson, Sierra Nevada from Manzanar-1944”. While Adams considered the resulting book to be patriotic, others considered it treasonous. With World War II still raging, many Americans had hateful feelings toward Americans of Japanese decent. Some praised his book while others burnt it. The book is now considered one of his rarest works as it only had one printing when it was published in 1944. When offering the Manzanar collection to the Library of Congress in 1965, Adams said in a letter, “The purpose of my work was to show how these people, suffering under a great injustice, and loss of property, businesses and professions, had overcome the sense of defeat and despair by building for themselves a vital community in an arid (but magnificent) environment… All in all, I think this collection is an important historical document, and I trust it can be put to good use.” Ansel Adams, despite his restrictions considered his photography at Manzanar his finest photo documentary work, but there was controversy as he didn’t cast a critical eye towards his subjects as did Dorothea Lange, Francis Stewart, Toyo Miyatake (who was interned at Manzanar) and others who photographed the camp. Some thought his photos didn’t address the injustice forced upon the thousands of Japanese Americans who were taken from their homes and held under military guard. Congressman Mel Levine (D-CA) who served in congress from 1983-1993 said the site should “serve as a reminder of the grievous errors and inhumane policies we pursued domestically during World War II and a reminder that we must never again allow such actions to occur in this country.” With help from the non-profit Manzanar committee and Congressman Levine, Manzanar became a National Historic Site in 1992, signed into law by President George H. W. Bush. 6