5 minute read

The Beaverbrook Tradition Continues for RL’s Youngest Students

On September 10, 43 new Sixies—along with intrepid Class I leaders and faculty chaperones— trekked to Beaverbrook in Hollis, New Hampshire, for a tradition that dates back nearly 60 years. >>

Upon arriving, Class VI boys were immediately met with their first challenge: a test of their knowledge of “the oldest school in continuous existence in North America.” Charged with successfully separating Roxbury Latin fact from fiction and producing the most correct answers in the questionnaire, Sixies face an uphill battle: Those well-versed seniors and teachers may purposefully throw them off track with bogus answers, allowing for the single time all year when our watchwords “honesty is expected in all dealings'' go out the window. >>

Advertisement

The day, organized by Class VI Dean Elizabeth Carroll, continued with team building activities (a low ropes course; the famously frustrating helium hula hoop game; an orienteering challenge that required a crash course in terrain maps and compasses). Before dinner, each Sixie addressed a letter to himself, to be opened at his senior retreat five years from now. The evening ended around the campfire, where Mr. Opdycke taught new boys The Founder’s Song, and Penn Fellow Jack Parker led an enthusiastic game of the math-lovers’ favorite “Flip Flop,” before it was time for s’mores. >>

>> Because of lingering concerns about COVID, this year’s adventure was not an overnight event. Rather Class VI gathered the day before, during special programming, to watch together the 1957 film Twelve Angry Men, with small group discussions afterward. (These were animated but decidedly more civil than the ones depicted on screen.) As they packed up and boarded the bus home that Friday evening, the Class of 2027 joined a brotherhood of RL men and boys who have sat around the campfire at Beaverbrook, singing about Roundheads and eating s’mores. It is a brotherhood that spans generations.

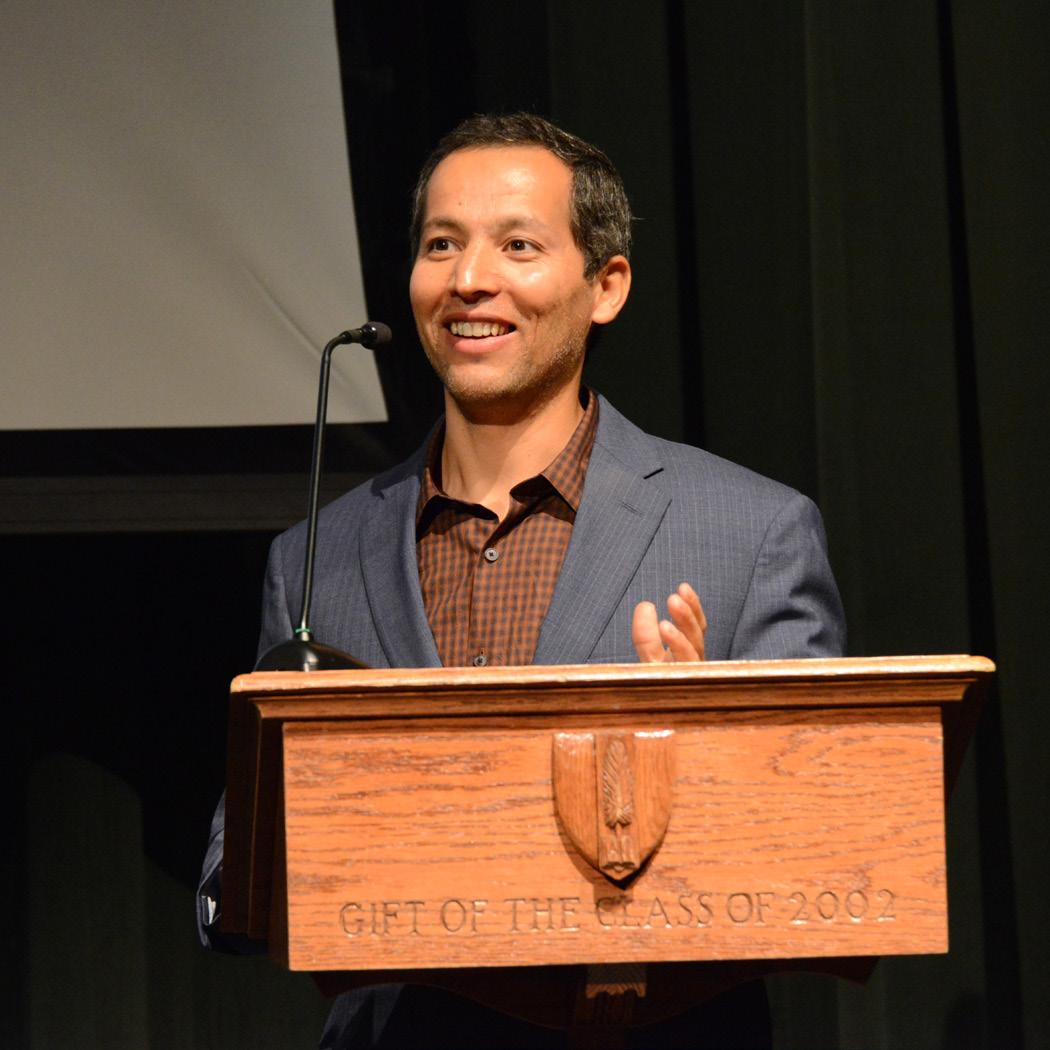

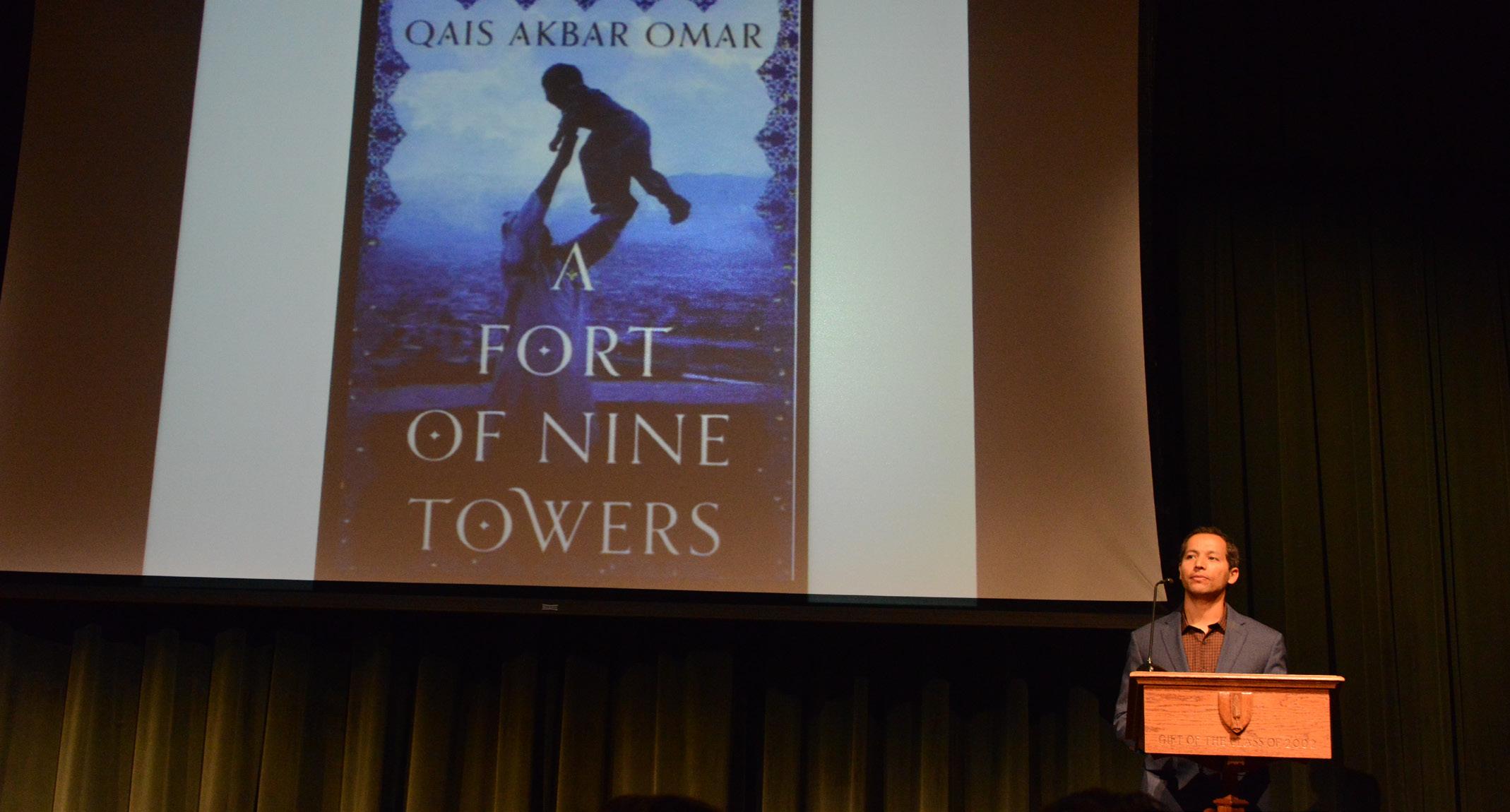

Afghani Author Qais Akbar Omar Shares His Story

On October 7, Qais Akbar Omar—author of the highly praised coming-of-age memoir A Fort of Nine Towers—shared his story with students in the Smith Theater. With photograph slides illustrating his account, Mr. Omar walked the audience through his experiences of living in Kabul, Afghanistan, during its decade-long civil war, under the rule of the Taliban, and post-9/11, after the arrival of American troops. He showed photographs of the culturally rich, modern, and sophisticated Afghanistan that predated the country’s turmoil of these last three decades.

“Especially as headlines have been dominated by the withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan after 20 years; the return of the Taliban to power; and the ensuing uncertainty in that country, we are glad to welcome to Roxbury Latin an eyewitness to contemporary history,” said Headmaster Brennan, in introducing Mr. Omar.

Mr. Omar’s memoir begins when he was eight years old, living an idyllic childhood in Kabul, surrounded by his large, colorful, and prosperous family. Mr. Omar, his siblings, his parents, and six uncles and their families all lived together in his grandfather’s spacious home. His grandfather was a carpet dealer, as was his father, who was also a champion boxer and physics teacher at Habibia High School, alma mater of Afghanistan’s former President, Hamid Karzai.

Mr. Omar’s early life in Kabul included the traditional kite flying competitions, popularized in the West by Khaled Hosseini’s novel, The Kite Runner. Life as Mr. Omar knew it at that time was changed forever with the emergence of the Mujahideen, the American-supported rebels who rid Afghanistan of its pro-Soviet government. They brought to Afghanistan and its people a decade-long civil war, displacing thousands of families and, in its savagery, leaving many more casualties. When it became too dangerous to continue to live in his grandfather’s home, the family traveled to a home owned by his father’s carpet-business partner, an 18th-century fort called the Qala-e-Noborja, or the “Fort of the Nine Towers.”

Throughout these years, Mr. Omar and his family were forced to endure unspeakable atrocities, and were saved from almost certain death by the coincidences of life: a former boxing student of his father’s, and then the kite-flying partner of Qais himself, became saviors rather than oppressors based on their prior relationships with Qais and his family. The family traveled

Mr. Omar and his family were forced to endure unspeakable atrocities, and were saved from almost certain death by the coincidences of life: a former boxing student of his father’s, and then the kite-flying partner of Qais himself, became saviors rather than oppressors based on their prior relationships with Qais and his family.

through Afghanistan in hopes of being smuggled out of their beloved country, but then the tragedy of September 11, 2001 intervened and the family was subjected to the United States’ strikes on the Taliban.

When the Taliban were forced out of Kabul, Mr. Omar and his family reclaimed part of their lives and their home. Mr. Omar helped to rebuild his family’s carpet business. He became an interpreter for the U.S military and worked for the United Nations. He developed a Dari-language production of Love’s Labour’s Lost and then co-wrote, with West Roxbury resident, journalist and playwright, Stephen Landrigan, an account of the experience in their book Shakespeare in Kabul.

During his presentation he shared photographs of his family; talked about the unconventional methods of fishing he enjoyed, introduced by Soviet troops; recounted the months he spent living in artfully adorned caves in the Afghan countryside and with a nomadic tribe; and about the losses he endured, including that of his family’s prosperous carpetmaking business.

Mr. Omar earned a bachelor’s degree in journalism from Kabul University and an MFA in Creative Writing from Boston University. A Fort of Nine Towers has been published in more than twenty languages. Mr. Omar has written for The New York Times, The Atlantic, and many other reputable publications. In 2014-2015, he was a Scholars at Risk Fellow at Harvard University.

Mr. Omar writes in the conclusion to his memoir: “I have long carried this load of griefs in the cage of my heart. Now I have given them to you. I hope you are strong enough to hold them.” After presenting to students and faculty in Hall, Mr. Omar joined several upper-level English and history classes, where he answered students’ questions about his life, his family, his country—then and now, and the craft of non-fiction writing. //