122 minute read

RL News & Hall Highlights

Ambassador Harriet Elam-Thomas is RL’s 17th Jarvis International Lecturer

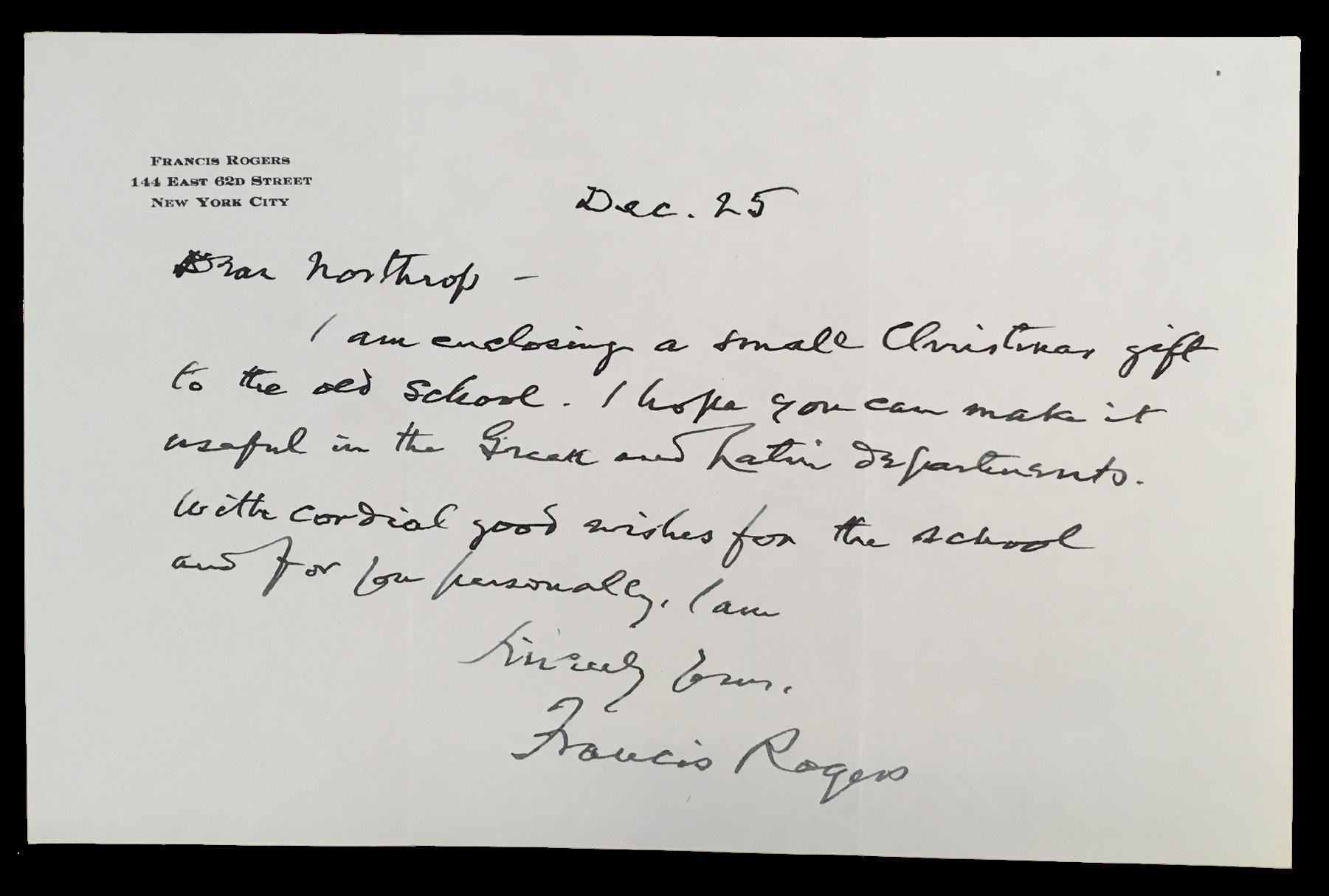

Since 2004, Roxbury Latin has welcomed 16 distinguished public servants and thinkers on foreign affairs to campus as part of the F. Washington Jarvis International Fund Lecture. Past speakers for this Lecture, named for the man who for thirty years led Roxbury Latin as its tenth Headmaster, have included former Federal Reserve chair Paul Volcker; former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates; homeland security advisor to President Obama, Lisa Monaco; and former Director of the CIA John Brennan.

Advertisement

On October 22, Roxbury Latin hosted the 17th annual— but first ever virtual—Jarvis Fund Lecture by welcoming Ambassador Harriet Elam-Thomas as our honored guest. Ambassador Elam-Thomas directs the University of Central Florida’s Diplomacy Program. Earlier in her career, she served as United States ambassador to Senegal and retired with the rank of career minister after forty-two years as a diplomat. A member of the United States Foreign Service beginning in 1963, the Ambassador also served as Chief of Mission to Guinea-Bissau; Acting Director of the United States Information Agency; and many other key, diplomatic roles in Greece, Turkey, Cyprus, France, Mali, and the Ivory Coast. She is the recipient of numerous honors and awards, including the U.S. Government’s Superior Honor Award, and the Lois Roth Award for Excellence in Informational and Cultural Diplomacy. Ambassador Elam-Thomas began her lecture with an account of her own path toward diplomacy. Raised in Roxbury, the Ambassador attended Roxbury Memorial High School (after a brief stint at Boston Latin, which ended when the Ambassador decided that learning Latin was “a fate worse than death!”), followed by undergraduate studies at Simmons College. Throughout her early educational experience, Ambassador Elam-Thomas did everything she could to prove that she was academically equal to her white counterparts. When she studied abroad for the first time—through Simmons’s experiment in international living in Lyon, France—she finally began to see her complexion as an asset instead of a liability; she found she could exist without having to justify her place in society. “This step of my journey changed my life and sparked my desire to live and work abroad,” she said. After several assignments overseas, she received a fellowship to attend The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University.

Once she graduated from Fletcher, Ambassador Elam-Thomas accepted a role as a cultural attaché in Athens, Greece. She taught herself Greek for the role, and she spent four years improving America’s image abroad and challenging the misperceptions Greeks had of America. In the mid-’90s, she was promoted to the Senior Foreign Service. “If it were not for my knowledge of a language,” she said, “I would not have been able to make that step on behalf of my country.”

The Ambassador expressed her wish that our country would incorporate more voices into the conversation on foreign affairs. America, she noted, is at a great comparative advantage thanks to the diverse range of culture, language, and aptitudes of its citizens. And yet this resource remains under-tapped. “The current demographic trends in the United States do not simply allow for a more diverse approach to international affairs, but they, in fact, demand one,” she said. “Given the increasing diversity of American society, minorities are developing their own perspective in foreign policy, priorities, and patterns. We need to determine how best to fashion and implement foreign policies from these varied viewpoints. Otherwise, the United States will fall behind its global competitors.”

Through her diplomacy work in Greece, Turkey, Senegal, and Guinea-Bissau, Ambassador Elam-Thomas learned important lessons surrounding cultural competency and civility that she wished to impart to RL boys. These were first and foremost lessons on decency, kindness, and even deference. “We really cannot superimpose our values on others,” she said. “We must learn to respect that when you are in another country, you are a guest there.” This is true for all diplomats, she explained, and it is important for them to be respectful, remain decent in the face of indecency, and apply to themselves a rigid standard of morality. She quoted Aaron Sorkin, saying: “Don’t ever forget that you are a citizen of this world and there are things you can do to lift the human spirit—things that are easy, things that are free, things that you can do every day.”

Special thanks to Jack and Margarita Hennessy, who have generously provided Roxbury Latin the philanthropic wherewithal in order that others might come to know and appreciate cultures and individuals around the world. Mr. Hennessy—RL Class of ’54 and former member of the Board of Trustees—and Mrs. Hennessy envisioned this fund helping to bring to the school distinguished thinkers on world affairs, as well as enabling the boys and faculty to experience cultures different from their own by sending them out into the world. We are proud to report that about 85% of RL’s upperclassmen have participated in a school-sponsored international trip. Special thanks also to alumnus Tenzin Thargay, Class of 2014, for introducing Roxbury Latin to the Ambassador, through his studies in international affairs at Columbia. //

Since 2004, Jack and Margarita Hennessy’s Jarvis International Fund has allowed the school to welcome some of the world’s brightest minds in politics, economics, history, and education to Roxbury Latin.

2004

Paul Volcker

Fmr. Chair, Federal Reserve

2007

Linda Fasulo

U.N. Correspondent for NBC

2010

Sir Eric Anderson

Fmr. Headmaster, Eton College

2013

Robert Gates

Fmr. U.S. Secretary of Defense

2016

Lisa Monaco

U.S. Homeland Security Advisor to President Obama 2005

Richard Murphy ’47

U.S. Ambassador, Diplomat

2008

Peter Bell

Former President of CARE

2011

Andrew Bacevich

Professor of International Relations and History, Boston University

2014

Bill Richardson

Fmr. Governor of New Mexico

2017

Mark Storella ’77

Senior Foreign Service 2006

Richard Haass

U.S. Ambassador; President, Council on Foreign Relations

2009

Gen. Anthony Zinni

U.S. Marine Corps, Ret.

2012

R. Nicholas Burns

Professor, Practice of Diplomacy and International Politics, Harvard Kennedy School

2015

Dr. Stanley Fischer

Fmr. Vice Chairman, Federal Reserve

2018

John Brennan

Fmr. Director of the CIA

2019 2020

Photo: NBC News

U.S. Marine Veteran Mansoor Shams Inspires Unity and Compassion

On November 10, Roxbury Latin celebrated its annual Veterans Day Commemoration Hall—this year via Zoom, allowing alumni veterans from across the country to tune in. The Hall featured guest speaker Mansoor Shams. Mr. Shams is a U.S. Marine veteran, having served four years in the Marine Corps, where he attained the rank of corporal (non-commissioned officer) and received several honors. He is also the founder of MuslimMarine. org, where he uses his platform of both “Muslim” and “Marine” to counter hate, bigotry, and Islamophobia through education, conversation, and dialogue.

Dressed in traditional Pakistani garb, adorned with an American flag pin, Mr. Shams began by addressing some misconceptions related to his Muslim faith. He continued by answering questions related to his experience in the military, the relationships he formed, and his mission to help unify people in an increasingly divided world. He spoke about some of the conversations he had and individuals he encountered during his “Ask Me Anything” tour, during which he carried a simple sign across America (25 states to be exact), that read “I’m a Muslim and a U.S. Marine. Ask me anything,” to engage the public in conversation and dialogue.

Mr. Shams has been featured by PBS, NPR, BBC, and The New York Times, and has made national TV appearances as a commentator on CNN and MSNBC. He has delivered talks and presentations not only at schools and colleges, but also for the National Security Agency, the U.S. Marine Corps, and state government agencies across America.

He has led various national initiatives including the 29/29 Ramadan Initiative, in which he teamed up with Veterans For American Ideals, to have military veterans spend a night at the home of Muslim families across America during Ramadan, to encourage fellow Americans to get out of their comfort zones to get to know each other. Mr. Shams is a term member on the Council on Foreign Relations.

In his opening Hall remarks, Mr. Brennan listed those RL alumni currently in active duty—graduates ranging from the Class of 1976 to the Class of 2017. As is tradition, the Hall program included a list of the 37 Roxbury Latin alumni who were killed in service to their country, dating back to the Revolutionary War.

“Through these RL men we can draw a direct and impressive line to those WWII vets honored by the school several years ago, to four RL alumni casualties in the Civil War, and to RL’s most famous veteran, General Joseph Warren, Class of 1755, who lost his life at Bunker Hill. The inclination to serve our country is a natural extension of John Eliot’s admonition to serve as he said, ‘in Church and Commonwealth,’” said Headmaster Brennan. //

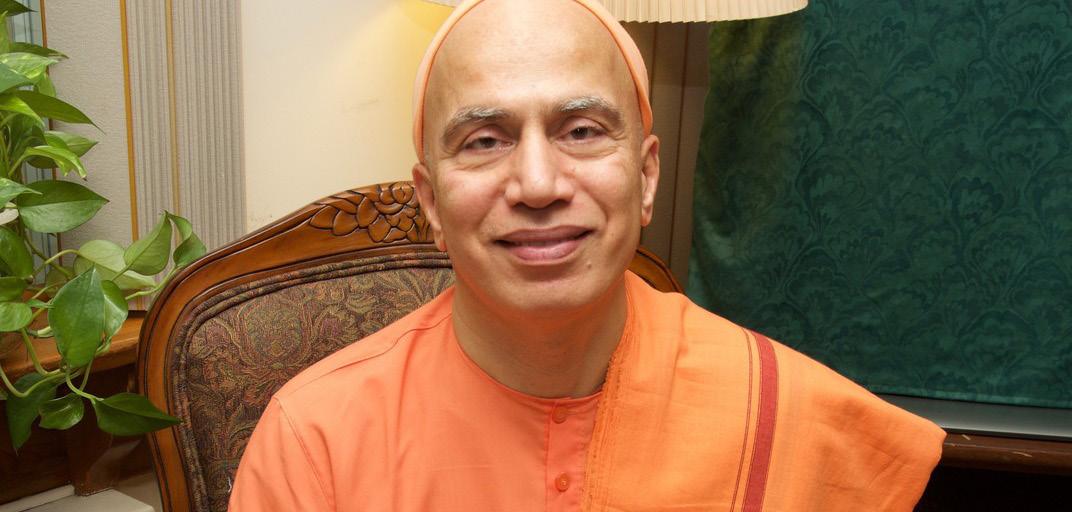

Swami Tyagananda on Light—Both External, and Internal

“On Saturday, members of the Hindu faith—including many in our own Roxbury Latin community—began the celebration of Diwali, one of the most popular festivals of Hinduism, which symbolizes the spiritual victory of light over darkness, good over evil, and knowledge over ignorance—virtues to which we can all aspire,” began Headmaster Brennan in virtual Hall on November 17.

The morning’s Hall continued a time-honored RL tradition of recognizing, and celebrating, the particular faith lives of members of our community. Joining the RL students and faculty on November 17 was Swami Tyagananda, who spoke about the tradition and celebration of Diwali, as well as the virtues of spiritual strength and how we might all work toward it. The Swami is a monk of the Ramakrishna Order; he is head of the Vedanta Society in Boston, and he also serves as the Hindu Chaplain at MIT and Harvard. He became a monk in 1976, soon after graduating from the University of Bombay, India. He has presented papers at various academic meetings and offers lectures and classes at the Vedanta Society, MIT and Harvard, and other colleges in and around Boston.

Swami Tyagananda acknowledges routinely that some people in the West find his name unusual. As he explains: “Swami” is the epithet used for Hindu monks, and the word means master. It points to the ideal of being a master of oneself, or being in control of oneself. The second part of his name was given to him when he received his final monastic vows. “Tyagananda” is a combination of two words, tyâga and ânanda: tyâga means detachment or letting go; ânanda means joy. Taken together, the word means “the joy of detachment.” It points to the ideal of letting go of all the nonessentials in order to focus on and hold on to the essentials.

In Hall, the Swami not only enlightened his audience about the history of the Diwali celebration, and the story of King Rama’s defeat over Ravana; he also reminded us that while the body and mind have limitations—that they can feel weak or strong—the spirit is limitless, and perfect. He spoke about the virtues of focusing on one’s spirit, and sharing that internal light with the world. He also reminded us that while our external markers vary greatly—our genders, skin colors, languages, religions—our spirits are universal, and it is often in learning about this great diversity of the world around us that we can help to understand our own identities and traditions anew. //

Professor Dehlia Umunna on Making Your Life Count for Good

Each year, Roxbury Latin begins the last school day before the Thanksgiving break with a tradition that is distinctly RL. Thanksgiving Exercises are an opportunity to, as Headmaster Brennan says, “turn our heads and hearts to the proposition of gratitude—for the country in which we live, for the freedoms and opportunities that are guaranteed by our being Americans, for our families and friends, for this community and others, for intelligence and discernment and deep feeling. For our gifts and aspirations, for good sense and hoped-for-dreams. Indeed we should live with an attitude of gratitude.”

This year, given the pandemic’s realities, Thanksgiving Exercises took place virtually, as students, faculty, and staff enjoyed prerecorded renditions of the traditional hymns We Gather Together, For the Splendor of Creation, and America the Beautiful. The Hall featured the resonant Litany of Thanksgiving—which includes a boy from each class—reminding us all of our “blessings manifold.” “The only thing wrong with Thanksgiving as a holiday,” Mr. Brennan asserted, “is that it may suggest that this is the only time to give thanks, or at least the most important. Each day, virtually each hour, offers an occasion for gratitude.” Delivering the Hall address was Ms. Dehlia Umunna P’21, a clinical professor of law at Harvard Law School, where she became the first Nigerian faculty member at age 42. In addition to teaching and conducting research focused on criminal law, criminal defense, mass incarceration, and issues of race, she is also the faculty deputy director of the law school’s Criminal Justice Institute. Through the Institute, Professor Umunna supervises third-year law students in their representation of adult and juvenile clients, in criminal and juvenile proceedings, in Massachusetts courts, including the Supreme Judicial Court.

Professor Umunna began her remarks by transporting her audience to the inside of a jail cell, where she found herself defending a nine-year-old Black girl named Anaya who had been charged with assault with a dangerous weapon, having thrown a book at the floor of her classroom, in the direction of her third-grade teacher, out of frustration. Prof. Umunna went on to describe what sparked her interest in studying law: immigrating to Los Angeles from London in the midst of the 1992 Watts Riots, and having witnessed her brother’s run-in with the law back in London. Prof. Umunna pursued a career as a public defender, “a lawyer who’s paid by the government to defend people in

court if they cannot afford to pay for a lawyer,” she describes. Before joining the faculty at Harvard, Prof. Umunna, for close to a decade, was a public defender in the District of Columbia, where she represented indigent clients in hundreds of cases from misdemeanor charges of theft, assault, and drug possession, to kidnapping, child sexual abuse, and homicide. Some of her cases received nationwide media attention.

“As a public defender, I truly entered spaces where I witnessed firsthand the realities of what it meant to be impecunious. I saw many families battling mental health concerns and learning disabilities while fending off aggressive police intrusion, harassment, and brutality. I observed firsthand the role of race and racism in the criminal legal system—understanding how unjust, unfair, and inequitable the system is.”

Prof. Umunna used her example—her commitment to making her life count for good—to implore RL students to do the same in their own ways, and to develop, always, the feeling and expression of gratitude for all the gifts and privileges we have been given, even in this particularly challenging year.

“This year has sent shockwaves through our psyche,” she said, “and as Thanksgiving approaches, we are exhausted and wondering, What do we have to be thankful for? We wonder if our lives have meaning, if our lives have purpose. There’s so much that we took for granted pre-pandemic, but as I say, every traumatic event, every setback, is an opportunity to reset for greatness. So how can you make your life count for good? First recommendation: develop gratitude as a virtue.” She went on to thank many individuals in the Roxbury Latin community who have enhanced her life and that of her son, Edozie, Class I.

“If you’re going to live a purpose-driven life, you must develop an attitude of gratitude for the privileges you have. When you develop gratitude as an attribute, you in turn develop empathy and compassion for others. You become less selfish, less judgmental. You recognize that but for your privileges, you could be that person sitting in a jail cell. That person standing in line at the food bank. That person without heat. Gratitude compels you to take stock of what you have and be truly thankful. Gratitude compels you to ask the question, ‘How can I serve others? What can I do to make a difference?’ Not just on Thanksgiving, but every day.” //

Rob “ProBlak” Gibbs On the Mission of Art, and Being a Good Person

On December 3, students and faculty were joined in virtual Hall by Rob “ProBlak” Gibbs, a celebrated visual artist who has transformed the cultural landscape of Boston through graffiti art since 1991. Growing up in Roxbury during hip-hop’s Golden Age, Mr. Gibbs saw the power of graffiti as a form of self-expression. The medium became a tool for him to chronicle and immortalize his community’s culture and history—a way to document, pay homage to, and beautify the City’s underserved neighborhoods. His remarkable artwork has brought him much notice and acclaim. Mr. Gibbs was featured last spring on the cover of Boston Globe Magazine for an issue titled “Why Art Matters.” In the spring, Mr. Gibbs also partnered with Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts as an artist-in-residence, in part creating a mural in his Breathe Life series at a vocational high school in Roxbury, not far from the Museum grounds.

In Hall, Mr. Gibbs began with a brief video of him and fellow street artist Marka27 completing a large-scale production beneath a bridge in Boston’s Ink Block, titled “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood.” The clip of ProBlak and Marka27 creating that mural offered students a sense of the scale, paint application, and intention behind the artistic piece.

Mr. Gibbs went on to answer questions from both students and adults, speaking about his start as an artist; his process; the challenges inherent in his medium; his inspirations and collaborations with fellow artists; and how his work has evolved over decades. The next day, Mr. Gibbs joined RL art classes, via Zoom, meeting with students from Class VI to Class I in Studio Art, Art & Technology, and Digital Design courses.

Beyond his artistic practice, Mr. Gibbs is also co-founder of Boston’s Artists For Humanity, a non-profit that hires and teaches young people creative skills—from painting to screen printing to 3-D model making. For the past 29 years, Mr. Gibbs has mentored and guided countless burgeoning, young artists through the organization, and continues today as its Paint Studio Director. In his mentor role, he explained, one of the key lessons he hopes to impart is “how to honor a commitment. No matter what [these young people] commit themselves toward, that’s a transferable skill that they can put toward anything. If you have the will to sit in front of a painting, or a piece of paper, you can put that drive toward finishing school work, studying, staying focused. I want [these kids] to be better than they were when they came in, as human beings.”

With a focus on arts education, Mr. Gibbs has conducted mentoring workshops for Girls, Inc., The Boston Foundation, Boston Housing Authority, and Youth Build, Washington, DC. He served as a guest lecturer at Northeastern for their “Foundations of Black Culture: Hip-Hop” course. He was the curator for BAMS Fest’s “Rep Your City” exhibition in 2019.

Mr. Gibbs is the recipient of a number of awards, including the 2006 Graffiti Artist of the Year award from the Mass Industry Committee, and the Goodnight Initiative’s Civic Artist Award. In 2020, he was honored with the Hero Among Us award by the Boston Celtics. His work has been featured by NBC, WBUR, the Boston Art Review, and Boston Magazine, among many other outlets. //

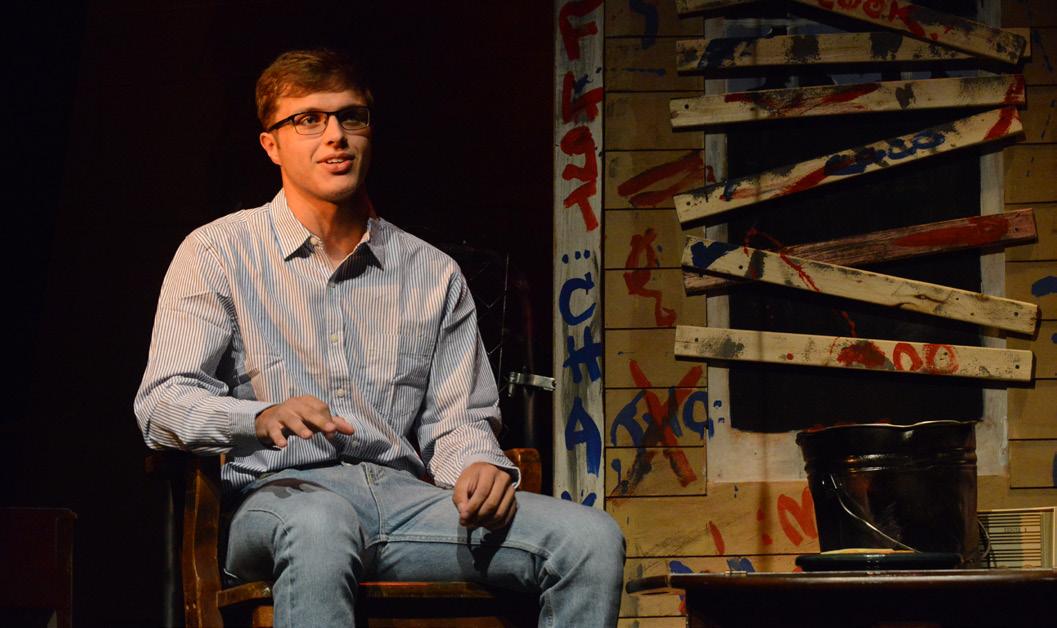

Aydan Gedeon-Hope (I)

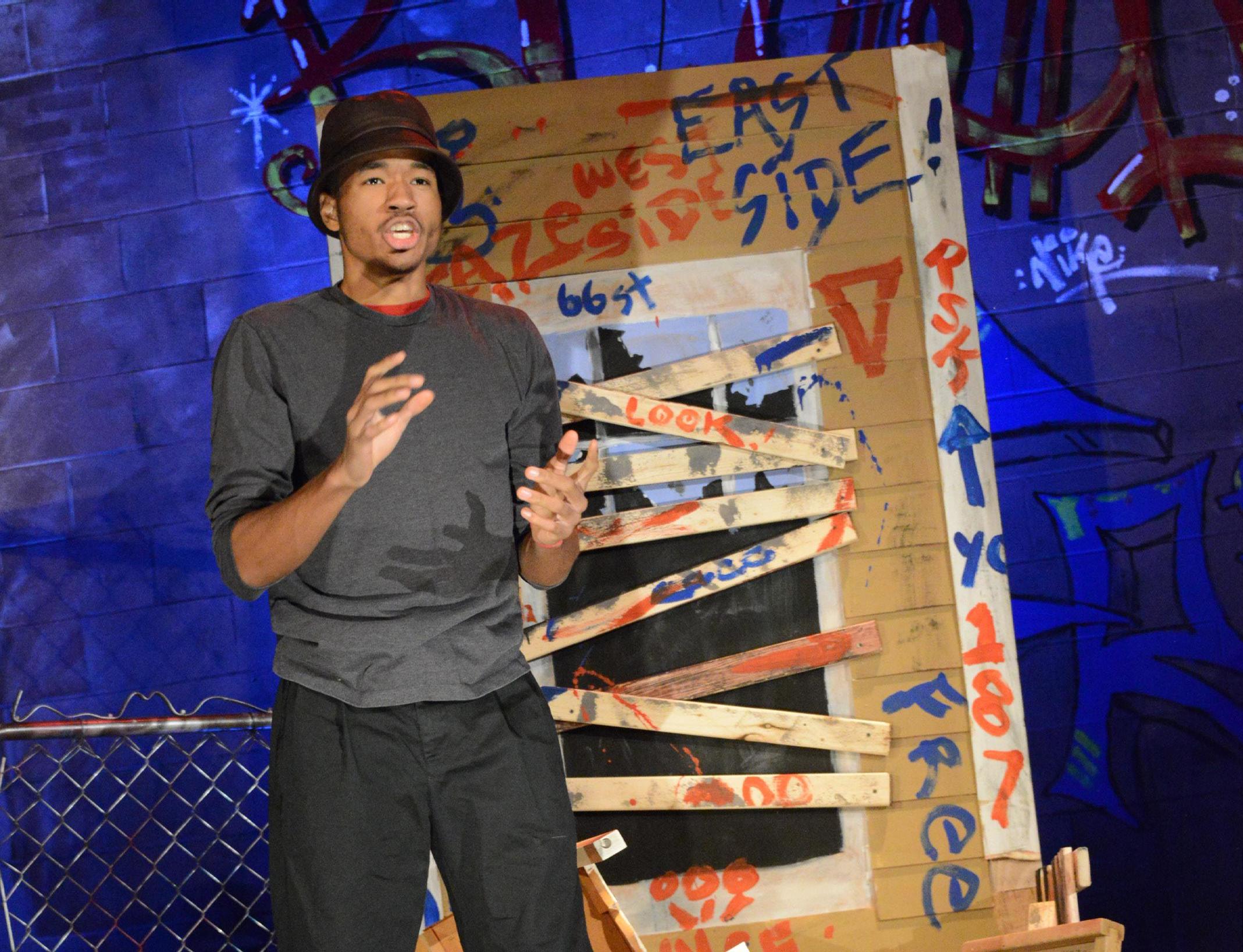

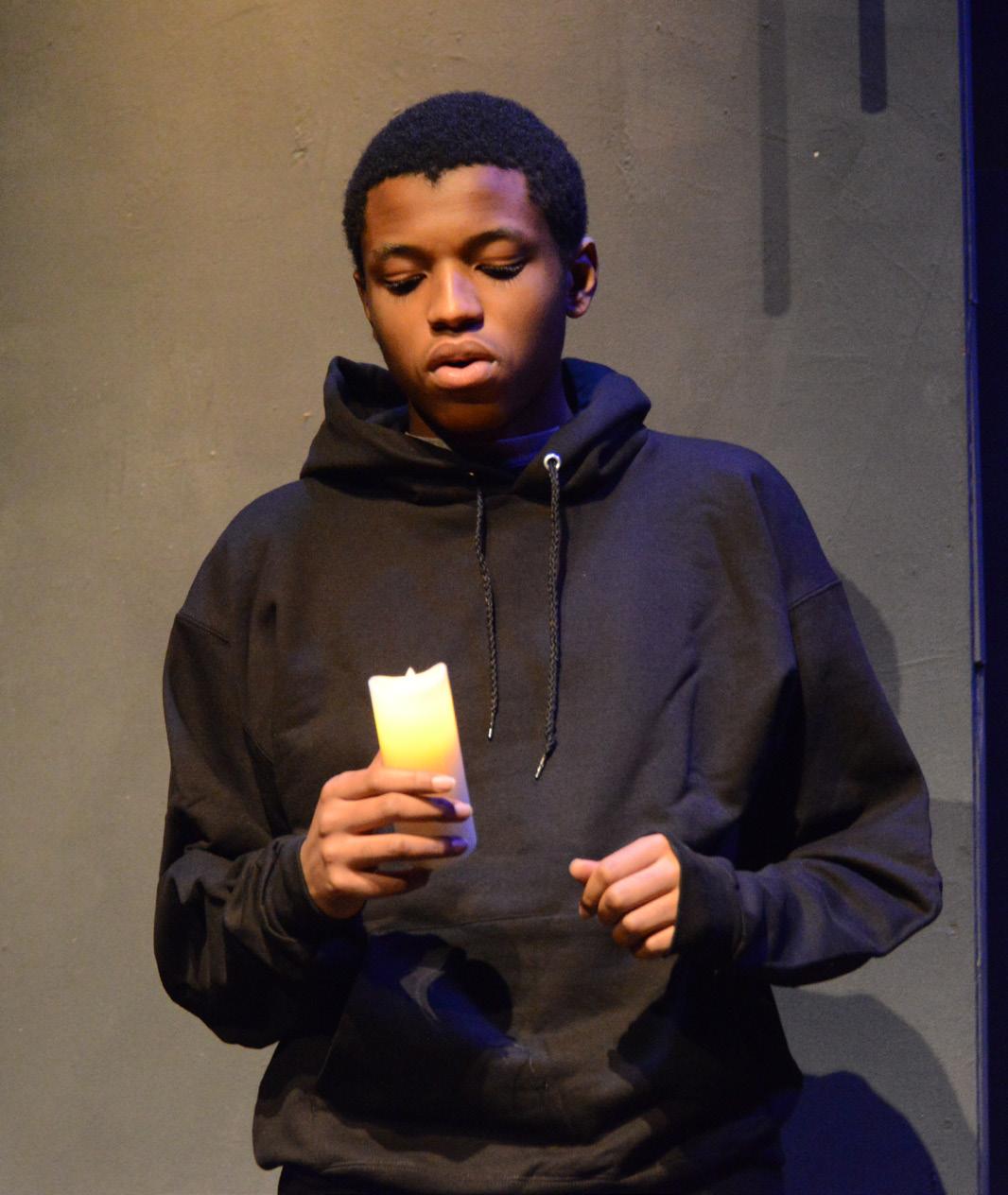

Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992, the Year’s Senior Play, Premieres Virtually

In planning for the school year, Director of Dramatics Derek Nelson knew that he would have to be creative in order to stage a drama production during a pandemic. His solution elegantly responded to two realities of 2020: The isolation and social distancing forced by COVID-19, and the uprising against racial injustice that marked the spring and summer, specifically. Mr. Nelson’s solution was to enlist Roxbury Latin’s oldest students—and their Winsor School and Boston Arts Academy counterparts—to stage Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992, a work of documentary theater by playwright and actor Anna Deavere Smith.

In the play—performed as a series of monologues—Ms. Smith uses the verbatim words of nearly 300 people whom she interviewed after the Los Angeles riots—which were sparked by the beating of Rodney King and the subsequent trial—to expose and explore the devastating human impact of that event. “Given the political and social unrest of the last eight months,” said the play’s director Mr. Nelson, “it is stunning, revelatory, and tragic that Anna Deavere Smith’s Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 speaks to us 28 years later.”

Twenty-one Roxbury Latin boys rehearsed the 22 men’s monologues beginning in September, both in-person and over Zoom, along with 12 girls from Winsor and one girl from Boston Arts Academy.

The monologues were filmed individually at both schools, and the resulting film was edited by Evan Scales, a Boston videographer. The production premiered on November 20, via livestream and YouTube. //

Edozie Umunna (I)

David Sullivan (II) Esteban Tarazona (I)

John Austin (III)

Emmanuel Nwodo (III) Matt Hoover (III)

Michael Rimas

Drawing on Ancestry, Dance, and Digital Design

For their final project of the fall semester, Class VI boys in Sonja Holmberg’s Digital Design course conducted research on their cultural heritage and learned about traditional dances from various countries and regions. Using Photoshop, they then created posters representing these traditional dances. Students had the option of either using a masking technique that they had learned in class or a technique that involves using the magnetic lasso tool and applying a Gaussian Blur to the background of the image. In the culminating presentation of their work, students spoke about the dance that they had chosen to represent, the technique that they used in their poster, and the ways in which their art implements at least two of the Elements of Art and Principles of Design discussed in class. The resulting posters are the colorful product of much hard work and inventiveness on the part of the Sixies. //

Jordan Bornstein

Denmark Chirunga

Colin Bradley

Chamber Trio Earns First Place in International Competition

The chamber trio of Alex Yin (II), Heshie Liebowitz (II), and Daniel Berk (I) entered this year’s international Great Composers Competition having never played together as a trio before. Yet this summer—looking for opportunities to make music with others, safely—the three boys wanted to fill the musical gap they were feeling on the heels of the spring’s quarantine. Initially, their plan was simply to play together, but when the opportunity arose to participate in the online competition, they took it.

The Great Composers Competition is a series of international music competitions for young performers organized in categories—for instrumentalists (piano, strings, winds, percussion), singers (opera, sacred music, art song, musical theatre), and chamber groups.

Daniel (French horn) plays with Alex (violin) outside of school, and Heshie (piano) had performed with Alex before; each admired the others’ musical skills. Though repertoire that involves the horn is limited, they selected Brahms’s Horn Trio, Op. 40. When they were pleased with how well the piece turned out, Heshie took the initiative of submitting the recording on the group’s behalf.

Knowing they needed large spaces in which to practice and perform while maintaining a safe distance, the boys were lucky to secure rehearsal space first in an auditorium on the Brandeis campus, and second, at a new Steinway piano retailer showroom in Newton, prior to the store’s official opening.

“This was my first time playing in a chamber trio,” says Daniel. “As Alex says, there’s not much to play for horns, but this piece is a hallmark of the repertoire, and it put me in the hot seat. I wasn’t used to minimal rehearsal—we only had two

rehearsals before we recorded—so that was a new experience, just getting the music and rehearsing on our own. We put it all together more quickly than any of us would have liked, but we were really pleased with how it came out.”

All three boys have been playing their instruments since they were very young—Heshie playing piano since before he can even remember. “When it comes to chamber music, what I enjoy most is playing with other people,” he says. “It’s fun to play with your friends, first of all, but it’s also rewarding because you get to explore with different sounds that you can’t make by yourself on your own instrument.”

“One thing I love about violin is the flexibility of the instrument,” says Alex. “You have so many options available to you. For instance, I can play solo music; I can play chamber music; or I can play in an orchestra.”

“Horn and brass are pretty different from other musical families, because they rely a lot less on finger technique and a lot more on trusting yourself and taking leaps of faith,” adds Daniel. “It feels like more of a mental game than a physical one. So when I play with instruments that demand a lot more technical skill—like piano and violin—it’s awesome to help produce that contrast of the long tone of the horn—which is not extremely complicated— with the sounds of the piano and the violin, which are just going a mile a minute, lightning fast. That combination of sounds is just a beautiful thing to help create.”

Now that the boys know what they can create together as a chamber trio, they hope to play together more in the future. The Brahms piece they performed has four movements, and the boys played the middle two. “The most iconic parts are actually movements one and four,” says Daniel, “and we were hoping to save them for when we can play in person together, and perform in person—hopefully on the Roxbury Latin stage!—as well.” //

Pianist Andrew Gu Selected for NPR’s From the Top

Andrew Gu (V) was recently selected and recorded for NPR’s nationally-renowned From The Top program—a premier music radio show, which celebrates the stories and talents of classically-trained young musicians. The episode featuring Andrew’s performance—Show 393, with host Peter Dugan—aired nationally during the week of December 14. Andrew performed Beethoven’s Sonata No. 7 in D Major; he was the youngest of the five teenage musicians featured on the episode, which also included saxophonists and violinists—hailing from Chicago, Illinois to Underhill, Vermont—and performances of pieces by Stravinsky and Reena Esmail.

Andrew, who has earned other accolades and honors for his skills as a pianist, started piano lessons with his mother, Helen Jung, and continued his studies with Alexander Korsantia and Hitomi Koyama. Andrew made his orchestral debut at age eight, performing Haydn’s Keyboard Concerto in D Major at the Music Fest Perugia, Sala dei Notari, Italy in 2015.

Several Roxbury Latin student-musicians have been featured performers on From the Top over the years. From the Top is a national, non-profit organization that supports, develops, and shares young people’s artistic voices and stories, providing young musicians with performance opportunities in premier concert venues across the country; national exposure to over a half million listeners on its weekly NPR show; and more than $3 million in scholarships since 2005. //

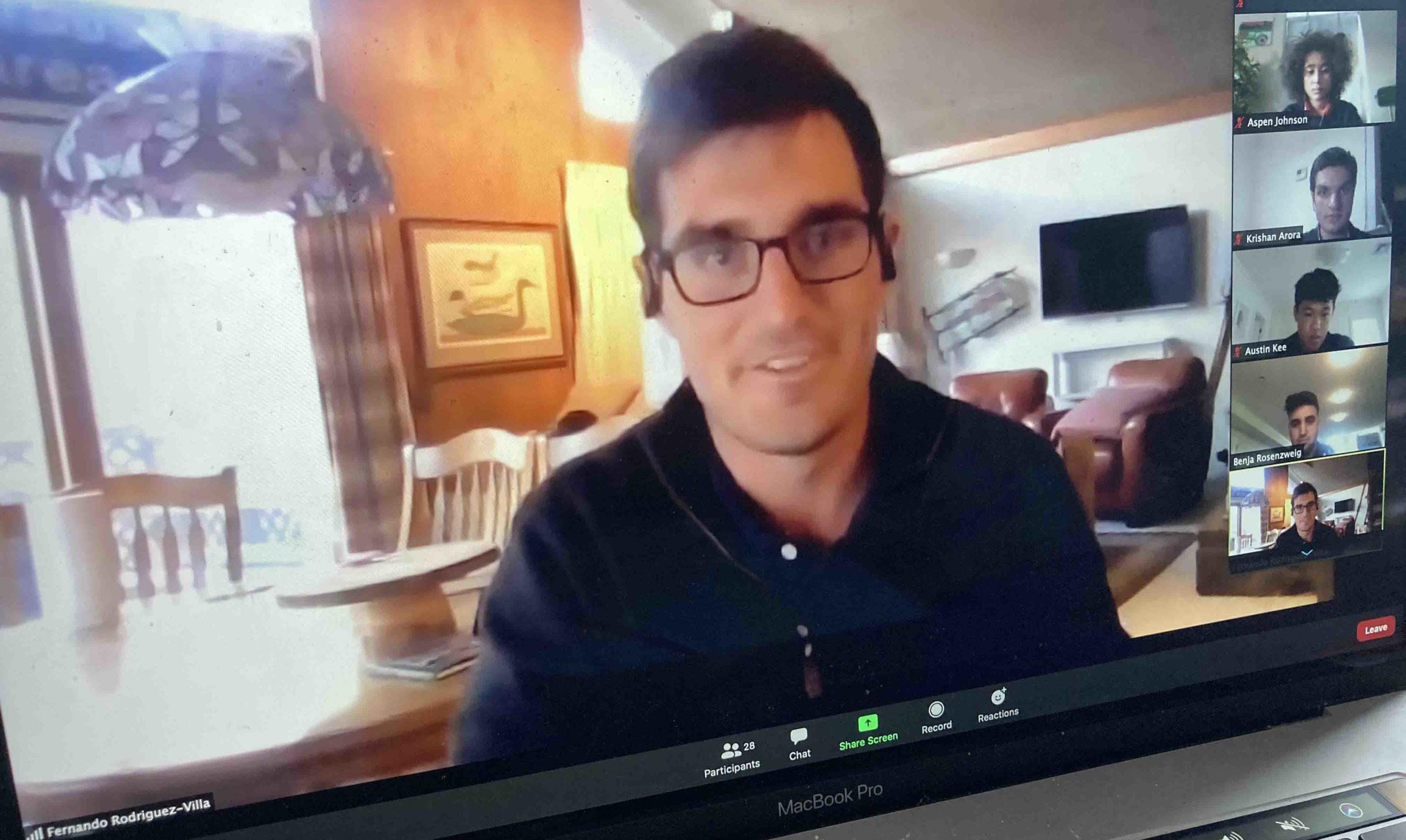

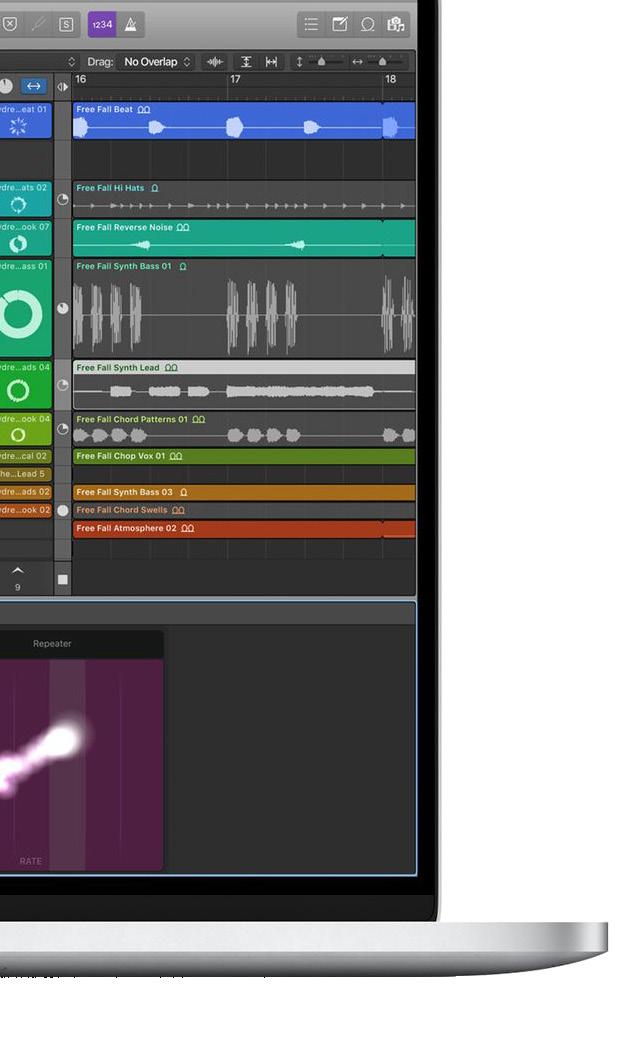

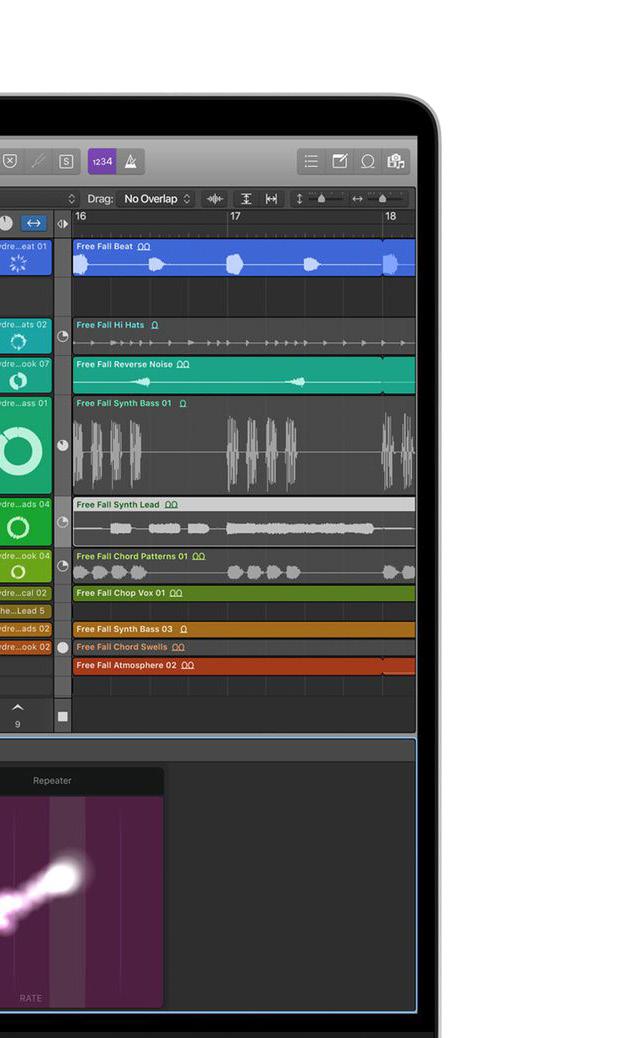

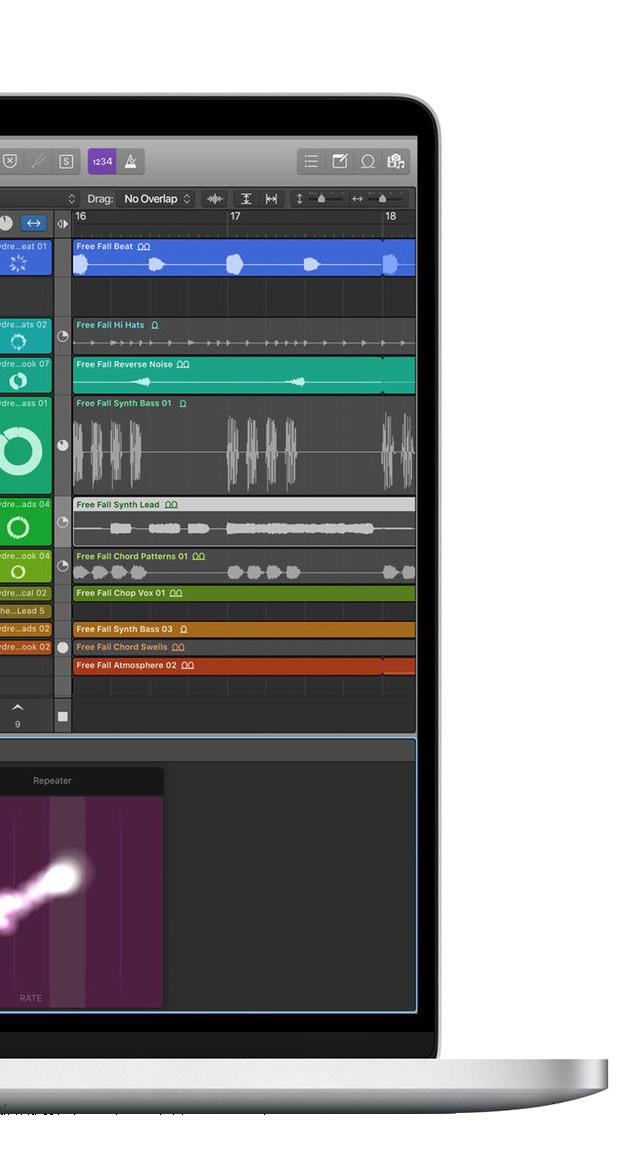

Fernando Rodriguez-Villa ’06 Speaks at RL’s Inaugural Innovation Exchange

On December 3, Roxbury Latin hosted its inaugural Innovation Exchange with keynote speaker Fernando Rodriguez-Villa ’06. Fernando spoke with students and faculty over Zoom, sharing his journey from RL student to co-founder of AdeptID. Students were able to engage with AdeptID’s technology during a group project, followed by a question and answer session.

“One of the most valuable parts of RL for me,” began Fernando, “was getting an early education in not being the smartest person in the room. At RL, you learn pretty quickly that there are a lot of people out there who are sharp in ways that you are distinctly not. The faculty there knew that I was a strong, good, fairly unremarkable student compared to some of the other students that I was lucky enough to share the classroom with. Whether I was at Dartmouth or in banking or beyond, I was never unfamiliar with being around people who were incredibly bright and had perspectives and insights that I wasn’t going to arrive at on my own.” Fernando is the founder and CEO of AdeptID, a start-up with an AI-enabled platform that predicts the success of transitions between different kinds of jobs. At RL, Fernando was active in theater and Latonics and played varsity football, basketball, and track. After graduation, he spent a year as a Hennessy Fellow at Eton College before attending Dartmouth.

Fernando left banking in 2014 to work at Knewton, which used machine learning to personalize learning, and since then Fernando—a self-described serial entrepreneur—has spent his career pursuing machine learning ventures around the world. In 2016, he co-founded TellusLabs, a satellite analytics startup that was quickly acquired by Indigo. At Indigo, he served as the Director of International Strategy.

“I liked banking,” said Fernando, “but it was clear to me within a couple of years that it probably wasn’t what I wanted for my long-term career trajectory. I started seeing growing companies and leading companies on the operational side as exciting.

“One of the most valuable parts of RL for me was getting an early education in not being the smartest person in the room. At RL, you learn pretty quickly that there are a lot of people out there who are sharp in ways that you are distinctly not... I was never unfamiliar with being around people who were incredibly bright and had perspectives and insights that I wasn’t going to arrive at on my own.”

“One client of ours was a CEO who had started his company from above his garage with two friends. They had grown to become a massive and important asset manager over 25 years. He was still close friends with the people with whom he had gone on that journey. He was beloved by that team, and in that camaraderie there was a lot that reminded me of RL. It was inspirational. “Simultaneously, I was fortunate to start learning from friends outside of work, about some of the trends in technology. I got into what was called big data, which is now known as AI or machine learning. I learned of the potential this technology had to generate predictions or insights at scale—to put that into software that could, in real time, answer pretty interesting questions. So I became obsessed with this one startup based in New York called Knewton, which was using AI on education data.”

Knewton was initially hesitant to hire Fernando, an investment banker with no professional experience in AI or education.

“‘You have this other set of skills,’ they said, ‘and we wouldn’t pay nearly as much as you’re making now,’” said Fernando. “It took a fair amount of work to persuade them that I was excited about the mission and was prepared to face the learning curve of the technology. It took several tries to make them comfortable hiring me!”

Knewton put Fernando in charge of international business development, sending him to Spain, South Africa, India, and Russia to expand the reach of the New York-based company.

“Knewton was a good stepping stone into the world of entrepreneurship,” said Fernando. “Within the world of startups and technology, there are a lot of very early stage companies; AdeptID, which we started this year, is in its preseed stage. As companies get larger, they tend to raise more money, get more customers, and hire more people. Knewton was in this later stage when I joined, and so there was a fair amount of risk that had been taken off the table.”

Fernando knew he wanted to get involved with an earlier-stage venture, so he quit his job and moved to Boston with his now wife, Emma.

“That job hunt was not particularly easy or comfortable,” admits Fernando. “I had to go for a lot of coffees to get a sense of founding teams I wanted to join, and ideas I could get excited about. That’s how I found TellusLabs, where I was paired up with two great technical founders who had built algorithms that could—just by looking at satellite images of crops—predict the crop yield per acre. Those kinds of

predictions of food supply were exciting, but the challenge was turning that technology into a business.”

In two years the founding trio at TellusLabs had expanded to a team of 14 data scientists and engineers, attracting the attention of one of its partners, Indigo Ag, whose technology fit almost perfectly with the direction in which TellusLabs was headed.

“As we were a customer of theirs,” said Fernando, “they approached us asking if we were interested in joining their company. Initially we said no, because we wanted to build our own independent company, but they made a persuasive offer. Most of the people who were part of TellusLabs are still working for the company and are still happy there. I was also happy to have gone through that, but working for Indigo, a multithousand-person company, I learned that I loved that early stage—a couple of people and an idea, a promising technology, and the building and uncertainty that comes with that.”

Fernando left Indigo early this year for his new startup, AdeptID, with co-founder Dr. Brian DeAngelis, to focus on emerging issues in the labor market.

“There seemed to be a lot of dynamics in the labor markets that looked like a matching problem,” said Fernando. “That is very much what machine learning and data science tend to be good at—solving matching problems.

“It’s incredibly hard to change jobs,” adds Fernando, “but something that’s made it easier for me personally is the fact that I have this very blue-chip education. I’ve had a lot of privileges and advantages that have resulted from that. People look at my story and say, ‘Perhaps he hasn’t done this thing, but because he went to these schools, and because he has these other stamps’ they’re willing to take a gamble on me.”

A large portion of the workforce doesn’t have the education and background that Fernando has, and so changing jobs is difficult. Transitioning between industries can feel nearly impossible.

“There are tens of millions of people who are unemployed right now who fall into this category,” said Fernando. “And then there are also people who are employed in industries in structural decline—job losses in hospitality and oil and gas and coal. We estimate around 35 million workers will need to find jobs in something very different than what they’ve done before.”

The entrepreneurial challenge for Fernando and Brian was figuring out the business of solving that problem. Could they excite people by the economic opportunity of trying to address those issues?

“There are certain sectors in which job growth or job demand is faster than the rate at which people can hire for them,” says Fernando. “In sectors like healthcare, renewable energy, and advanced manufacturing—roles like machinists, pharmacy techs—employers are struggling to find people who are certified or ready to do these jobs.”

It is that complex dynamic of supply and demand that drives AdeptID, which uses big data to look more deeply at workers and their underlying skills to find potential cross-industry career matches.

“Just because you’ve been a service unit operator for Chevron doesn’t mean that you can’t do one of these other growing jobs,” says Fernando. “In fact, some of the skills you’ve picked up are incredibly relevant and mean that you are more likely to fit into these new roles. That was our anecdotal perspective, but I had to go out and make it legible—to take these stories and put them into a data format that can allow us to support that perspective from an algorithm standpoint.”

Fernando and his AdeptID co-founder, Dr. DeAngelis, work with employers and vocational training providers in New England as well as the Midwest and Sunbelt to acquire data on hiring patterns and placement rates to help train their models. During the recent session, RL students used sample data from AdeptID, which mapped the “distance” from jobs in one industry to jobs in another on the basis of skill, to work on group projects.

“What we find when we do this,” says Fernando, “is that there are some jobs that are intuitively similar—for instance pharmacy aids and pharmacy technicians—and others whose connections are a little less obvious, like a cashier or food service worker with that same pharmacy technician role. It turns out there’s actually a fair amount of overlap. If the data starts to say that, we say, ‘Okay, can we confirm that?’ and the hiring managers we’ve spoken to at places like Boston Medical have agreed.” //

Gina McCarthy, Lisa Monaco, Marty Walsh

Recent Hall Speakers and Friends of RL Nominated Among President Biden’s Top Advisors

Roxbury Latin is honored each year to host an impressive range of guest speakers—expert and accomplished leaders, thinkers, researchers, artists, and public servants—who present to the boys and faculty on a broad range of topics. Three recent Hall speakers and friends of Roxbury Latin— Gina McCarthy, Lisa Monaco, and Marty Walsh—have been tapped for close advisor roles and cabinet positions in President Joe Biden’s administration.

The Honorable Gina McCarthy—former Administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under President Obama—spoke to students and faculty in Hall on November 13, 2017, delivering the keynote address in the year’s Smith Scholar series focused on global climate change. On campus, she discussed her work in the Obama administration, offering her assessment of their accomplishments, the importance of the Paris Climate Accords, and the changes that could come with the Trump Presidency. She was generous with her time, spending another hour speaking to and inspiring seniors who were taking the Environmental Science course that year. “Climate change isn’t just a threat to public health—it’s not about polar bears. It’s about you, your health, the health of your children,” said Ms. McCarthy, identifying the economic threat as well: The stronger and more frequent storms in the Caribbean and the fires in the west call for billions of off-budget dollars that aren’t allocated. “The reason people are accepting the science of climate change is because they are feeling it,” she asserted. Ms. McCarthy currently leads the National Resources Defense Council. In her new role she will serve as a senior adviser to Biden, coordinating climate change policy throughout the government. She will be the stateside counterpart to John Kerry, who will serve as the administration’s international climate envoy. Lisa Monaco—who was serving as Homeland Security Advisor to President Obama at the time—delivered Roxbury Latin’s Jarvis International Lecture on October 17, 2016. Ms. Monaco is an alumna of our neighboring Winsor School, and she has recently been nominated as Deputy Attorney General to the Biden administration.

Class III Serves, Undeterred

Service is central to Roxbury Latin's mission, and Class III continued that commitment this fall—despite the challenges of the pandemic—when they volunteered their time to help elderly neighbors, single parents, and local parks with various fall clean-up needs. // In Hall, Ms. Monaco described not only her role as President Obama’s advisor—working with the President and the rest of the National Security Team to help keep the country safe—but also her own public service journey, which began soon after college when she worked in the Senate on the Judiciary Committee under then-chairman, Joe Biden. “I got bitten by the public service bug,” she explained. In closing, she implored RL students to pursue a career in public service. “Public service needs you,” she said. “In the coming years, our government, our nation, and our world will need people who can understand and operate in a fast-paced and wired world while remaining grounded in our enduring values… What John Eliot called ‘godly citizenship’ three and one-half centuries ago, is needed now, more than ever. And when I look around this room, when I think about the skills and smarts in this hall, I am confident that whatever challenges come in the decades ahead, your generation will rise to meet them.”

Finally, Boston Mayor Marty Walsh delivered RL’s Founder’s Day keynote address in 2014, when he spoke to students about persisting through struggles, and focusing on opportunities, by way of his own, personal story. “As a young person, I took a lot of lefts and rights where I should have gone straight,” he said. By his late 20s he acknowledged his trouble with alcohol and went into rehab. “Everyone in this room knows someone who is struggling. Sometimes life is not a straight line. I had loving friends and family to help me take the right path.” Mr. Walsh reminded students that they will encounter challenges and be faced with choices. He admonished the boys to follow their dreams, and listen to that inner voice, and especially to recognize the tremendous opportunities before them. On January 20, 2017, Mayor Walsh also led the ceremonial puck drop, commemorating the grand opening of RL’s Indoor Athletic Facility and inaugural home game hosted in Hennessy Rink. He spoke from center ice prior to the game, to the hundreds of RL fans in attendance, congratulating Headmaster Brennan and the school’s leadership for building a beautiful facility that would be used by Roxbury Latin athletes and neighborhood youth groups alike. Mayor Walsh has been nominated to become President Biden’s Labor Secretary. //

Dr. Lisa Piccirillo On the Beauty of Mathematics

In 2018, Lisa Piccirillo—a graduate student, and Boston College alumnus—learned about the Conway knot—a conceptual, mathematical tangle that had gained mythical status. (For more than 50 years, no mathematician had been able to determine whether Conway’s knot was “slice.”) One week later, Ms. Piccirillo produced a proof that stunned the math world.

On January 14, Roxbury Latin welcomed, in virtual Hall, Dr. Lisa Piccirillo, an assistant professor at MIT who specializes in the study of three- and four-dimensional spaces. She is broadly interested in low-dimensional topology and knot theory, and employs constructive techniques in four-manifolds. As a young graduate student, Dr. Piccirillo gained international fame for proving that the Conway knot is not, in fact, “slice.”

In Hall, Dr. Piccirillo began by walking students through an example of determining whether a given knot can be turned into an unknot by executing crossing changes. (This required the introduction of some topological vocabulary—knot diagrams, unknots, crossings, crossing changes, algorithms, sliceness.)

“A knot is just a circle,” she began, “but we’re going to think about the circle as sitting in three dimensional space. I don’t have any firm requirements on this circle being geometrically rigid. In fact, anything you can build by taking an extension cord, and making a huge mess out of it, and then plugging the ends together, is a knot.”

After bringing students and faculty through this illustrative process, Dr. Piccirillo spoke more broadly about mathematics education, math as a language, and about the creativity versus practicality of the work that she does every day.

“I think math is a two part adventure,” she said. “First we define objects, and then we prove facts about those objects using really precise, careful, logical arguments. This definition of math might seem foreign to you; in your education right now you’re doing a lot of learning objects. One of the objects we talked about this morning, crossing changes, that’s more of an operation, an action, and you do a lot of learning operations in school. The objects you meet are things like fractions or polynomials, and then you spend heaps of time adding the fractions, or factoring the polynomials, doing operations to these objects… Ultimately mathematicians want to know: here’s the thing that exists, and here’s everything that’s true about it.

“I like to think about learning math as being very similar to learning a language… Approaching math like that helps us dispel a common myth that there are ‘math people’ or ‘math geniuses.’ Another thing about doing math is that you have to be prepared to fail all day, every day—except on a very small number of good days when you write something down.

“Every time I approach a hard problem, I think, ‘Okay, this is not going to work, but I want to understand why it’s not going to work. So here’s an approach. Let’s see what goes wrong.’ Trying something, and understanding why it failed, progresses you toward understanding the problem.”

During a lively and extended Q&A session, students and faculty asked Dr. Piccirillo about “Eureka!” moments, practical uses of knot theory, the role of mathematics in the modern world, how she gets through “stuck” moments, her thoughts on Euclidean geometry, her favorite theorems, and the mindset she enlists in attempting to solve the “unsolvable.”

After earning her bachelor’s in mathematics at Boston College, Dr. Piccirillo earned her PhD from University of Texas at Austin. In addition to receiving an inaugural Mirzakhani New Frontiers Prize—recognizing outstanding, early-career women in mathematics—she was also recently named one of WIRED Magazine’s “People Who Are Making Things Better.” Dr. Piccirillo spent her COVID fall as a visiting researcher at the Max Plank Institute for Mathematics in Bonn, Germany. //

Photo: Kelly Davidson for Boston College Magazine

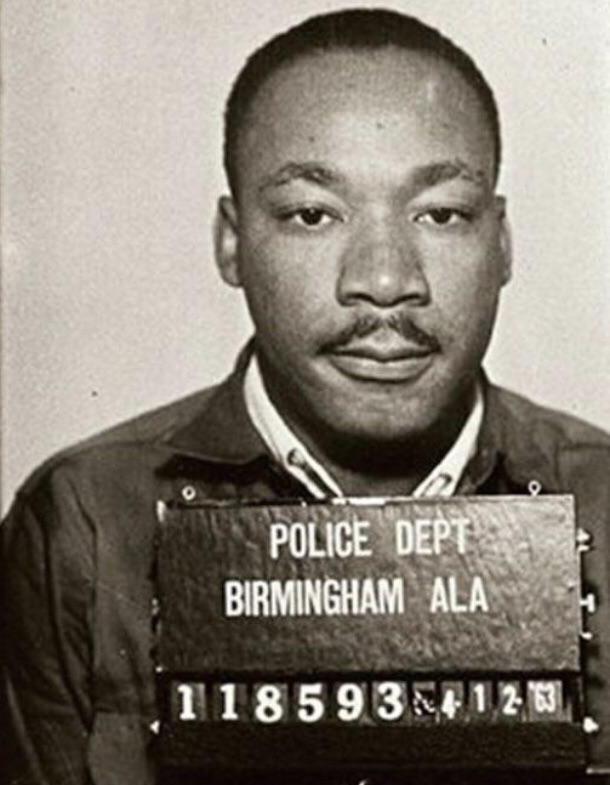

Honoring the Legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“Today, we gather to commemorate the life and work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.,” began Headmaster Brennan in virtual Hall on January 19. “We pause to recognize the contributions of this remarkable man and to consider anew the principles of justice, equality, and brotherhood—principles he pursued ardently and about which he spoke eloquently. While the United States today is blessedly different from the United States of Dr. King’s lifetime, racism and bigotry persist, and there continue to be opportunities for all of us to stand up for the values that Dr. King espoused. The prejudices and hatred that Dr. King worked so hard to eradicate remain in too many heads and hearts… As we affirm that Black Lives Matter, we also acknowledge that our work goes ever on—improving our individual relationships and attitudes but working on eradicating systemic racism, as well.”

After Mr. Brennan’s introduction, Aydan Gedeon-Hope (I) read Dr. King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” Following the reading, Edozie Umunna (I) shared his own reflections on Dr. King’s letter, citing not only the context in which King wrote it—as a response to a letter from eight Alabama clergymen—but also the dynamics at play during King’s lifetime that persist today. (Read Edozie’s complete remarks on page 26.)

Eric Auguste (I) then read a very personal perspective on Bayard Rustin—the civil rights and gay rights leader and activist—which Eric wrote as his Senior Speech, as part of his English class. (Read Eric’s complete essay on page 28.)

The Hall included time for students, faculty, and staff to learn more about the hymn “Lift Every Voice and Sing”—long considered the Black National Anthem—through CNN’s interactive account of the song’s conception and context. Concluding the Hall was a virtual performance of “Lift Every Voice and Sing” recorded by RL’s Glee Club in spring 2020, which has been viewed more than 30,000 times on Facebook and YouTube.

“While Dr. King as a preacher believed in the power of the spoken word as a way to change people’s minds and hearts,” concluded Mr.

Brennan, “he also knew that significant change could only come about through action, civil disobedience, changing institutions, and reaching out to many different kinds of people. He knew the importance of acting on principle when words could only begin to tell the tale. Given the divisiveness and prejudice that openly persist in our country, our vigilance, activism, and principles are consequential; we still have work to do if we want to achieve the social equality envisioned so many years ago by Dr. King. This work is the responsibility of every one of us.” //

Reflections on “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”

by edozie umunna, class i

I’ve read MLK’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” countless times in my life, but I don't think I ever really understood it at its full depth until these

past two weeks.

When Mr. Brennan asked me to reflect on the letter, I approached the task with a certain confidence. I was familiar with the text. I knew what it was about. And most importantly, I knew what the letter meant to me.

But there was one crucial aspect of the letter that I failed to understand: the context. What I didn't realize is that “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” was actually in response to a letter from Alabama clergymen.

These men banded together to send a message to the imprisoned Dr. King, to address the recent peaceful protest he had taken part in, in the state of Alabama. The letter from the clergymen provided a whole new dynamic to my interpretation of Dr. King’s letter.

In their own words, the clergymen’s letter was an appeal for “law and order” and “common sense.” They believed they were now confronted by a series of demonstrations by some of their Negro citizens, directed and led in part by outsiders. They believed that these demonstrations were unwise and untimely. They went on to say that while hatred and violence have no sanction in their religious and political traditions, such actions or extreme measures incite hatred and violence, however technically peaceful they may be. They close their letter by urging their own Negro community to withdraw support from these demonstrations, stating simply that when rights are consistently denied,

the cause should be pressed in the courts and the negotiations among local leaders, not in the streets. Should all this be done, they believed the Negro community of Birmingham would have taken steps toward a more unified city. Now, there’s a lot to be unpacked from the clergymen’s letter, but there’s one overarching point they touch on that I think is especially important to note—the idea of unity.

This was something that really jumped out at me, because I believe it has a particular pertinence to the United States at the moment. Through their words, the clergymen made clear that ending the protest in Birmingham was the only way in their eyes to establish unity in the Alabama town. Now, as we heard in the letter that was read, Dr. King pushes back on this idea, stating that the positive discourse that’s sparked by the protests is what will lead to a more unified city. My question is this: Why are purely peaceful protests somehow an attack on unity? Why is it that a movement consisting of nothing more than Black Southerners exercising their most basic of human rights causes a state of total division within the community? And the answer to that is this: Any attempt to disrupt the hierarchy of oppression will always be viewed as an assault on unity.

Dr. Martin Luther King is without a shadow of a doubt the most peaceful leader of the American Civil Rights Movement. As we see from his words in “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” he wants absolutely no part in clashes, fights, or any other form of violence. And yet, his actions of raising a sign in the street, sitting at a diner counter are seen as divisive. It’s not because of any direct deleterious effect that his protest had on the people of Alabama, it’s simply the fact that he dared to tear down the strongholds of hate and to question the privilege for White Americans that made for his protest to garner such criticism from these clergymen.

It’s the same dynamic that made millions of Americans around the country tell Colin Kaepernick to stand up. The same dynamic that caused Laura Ingraham to tell LeBron James to shut up and dribble. The same dynamic that caused more than 100,000 Alabamans to cheer on as Donald Trump referred to protesting NFL players as sons of bitches. It’s the same dynamic that gives the U.S. government pause in punishing all those responsible for the attack on our Capitol to the fullest extent of the law. It’s all in the name of preserving our country’s unity.

If there’s anything I took from Dr. King’s letter, it’s this: an effective protest will always be labeled divisive by the oppressor. No matter how you protest, no matter when you protest, no matter where you protest, it will always be viewed as invalid by those whose position of power it threatens to dismantle. When your objection comes under criticism, you’re doing something right. But what Dr. King charges us to do is to push on in these moments. As he sat in that 6x8 jail cell, reading the demand from some of the most powerful White men in the state to stop his protest, he mustered up the courage to refuse their criticism. I encourage each and every one of you to do the same. Whatever belief you stand for, whatever cause you fight for, do not let criticism be the reason that your voice is silenced. And let’s hope that someday soon, those radiant stars of love and brotherhood will shine over our great nation once more. //

Thank You, Bayard Rustin

by eric auguste, class i

I want you to imagine something. Imagine you are lying awake in the middle of the night because you can’t sleep. The hum of the air conditioner fills the silence of your bedroom. You toss and turn, angry because you are unable to fall asleep. Your heart is beating

at a speed that feels almost harmful and your hands are clammy. You sit up because it is getting harder to breathe. In. Out. In. Out. You can’t back out now. Tomorrow, you are finally going to come out to your parents. Well, you would if you weren’t straight.

To so many people, coming out isn’t a milestone that they have to accomplish in their lifetime. Approximately 95% of all men identify as heterosexual. Ninety-five percent. Almost every single one of those people will never have to feel the terror of coming out. I am not one of those people. But I don’t want to focus on my story. Instead, I want to turn your attention to a different time. A time when someone like me, differentiated by their race and sexuality, would be looked down upon.

Over the next few minutes, I would like to introduce you to Bayard Rustin. A gay, Black man born in the year 1912, Rustin lived his life suffering many hardships, constantly being battered because of his sexuality and the color of his skin. However, that didn’t prevent Rustin from fulfilling the role of an esteemed Civil Rights Activist from a young age. By the end of this speech, I want every single one of you to understand why Bayard Rustin, in the face of great adversity, was a man of great courage and question why he isn’t as well known as he should be.

Before I begin talking about his role in the Civil Rights Movement, I want to give you some background about Rustin’s life. Bayard Taylor Rustin was born into an unusual family dynamic. He was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, to a 16-year-old woman and with his father absent from his life. He was raised by his grandparents, believing that they were his real parents and his mother was actually his sister. In his teenage years, Rustin wrote poems and played on his high school football team, and according to a PBS article I found, there is lore that he staged an impromptu sit-in at a restaurant that would serve his teammates and not him. After college, to continue this

work, Rustin devoted himself to fighting for civil rights, and he participated in several groups that helped him further his goal. Rustin joined groups like the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the Congress of Racial Equality, and later he would join the Southern Christian Leadership Conference led by Martin Luther King Jr. Involved in these groups, Rustin traveled the country, speaking and inciting change everywhere he went.

However, in order to bring about these necessary changes, Rustin constantly threw himself headfirst into danger. Because of the color of his skin, Rustin was automatically put in dangerous situations by simply existing. Just like any Black person who lived during the early to mid-20th century, Rustin had to deal with the same challenges, like sitting in the back of the bus and being denied access to certain “White Only” businesses. I want to focus on one story I found that distinguishes Rustin as a man who put the sake of his people before his own safety. In an audio recording that was thought to be lost, Rustin provides the details of the day he realized it was necessary for him to come out. One day, Rustin boarded the bus and, like normal, he started to make his way to the back. On his way there, a white child playfully grabbed and pulled at the ring necktie he was wearing and was immediately scolded by his mother for touching him. From the recording I mentioned earlier, we know what was going through Bayard’s mind in that moment. Bayard said, “If I go and sit quietly at the back of that bus now, that child—who was so innocent of race relations that it was going to play with me—will have seen so many Blacks go in the back and sit down quietly that it's going to end up saying, ‘They like it back there, I've never seen anybody protest against it.’” Bayard’s revelation led him to take the dangerous path, on which he was arrested in order to preserve the innocence of that child as best as he could. But that wasn’t the only realization Bayard took away from that experience. In reference to his sexuality, he said, “It occurred to me shortly after that it was an absolute necessity for me to declare my homosexuality, because if I didn't I was a part of the prejudice. I was aiding and abetting the prejudice that was a part of the effort to destroy me.” By coming out and being open about his sexuality, Bayard once again chose the route of most discomfort over the easy one to fight against injustice.

So far, I’ve told you the “how” and the “why” Rustin became an effective civil rights activist. That brings us to what he actually did. I wouldn’t be doing this man justice if I left this important piece out. Bayard was a key organizer of the March on Washington in 1963. And not only that, but he was also one of MLK’s key advisers and strategists. As you may already know, the March on Washington is most famous for Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. So why is it that the man behind the movement, Bayard Rustin, is barely given any credit? Well, during the twentieth century, being gay was not exactly praised. In fact, Rustin was often ostracized from his own community of blacks because he was so up-front about his sexuality. And, there were no legal protections for gay couples, making it tougher for people like Rustin and his partner, Walter Naegle—whom he had to legally adopt in order for them to have a relationship. Taking these circumstances into account, it is easy to understand that Rustin often didn’t take the spotlight. To give you an example that might shock you, Martin Luther King and Rustin had a somewhat “troubled” relationship. Rustin began working with King in the mid 1950s, lending him support in his boycotts and teaching him the ways of Gandhi and peaceful protest. However, in 1960, even though the two men worked closely and made great progress, the tension of Bayard’s sexuality caused problems between them. Ready to lead a march outside the Democratic National Convention that year, MLK was given an ultimatum by a fellow black leader: get rid of Rustin or he would tell the press that he and King were gay lovers. To my surprise, MLK called off the march and pushed Rustin away, causing him to resign from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. On the subject, James Baldwin—another gay Black man living in the same time period—wrote that King “lost much moral credit … in the eyes of the young.” Even so, Rustin kept pushing on and eventually planned the March on Washington he had been waiting for, all without complaining about how he was treated along the way.

Do you remember that night I had you imagine? That night was my reality. That was one of the hardest times of my life. However, I am not asking for sympathy. I simply want you to understand that my experience is not the default. Consider what it was like for Bayard Rustin 100 years ago. People like Rustin didn’t and still don’t get the luxury of living easy lives because of a trait they can’t change, and yet, he made it his mission to change the way people viewed race and sexuality. The world has taken big steps in the right direction, but it’s time to stop letting heroes go unnoticed. Thank you, Bayard Rustin, for all that you’ve done. //

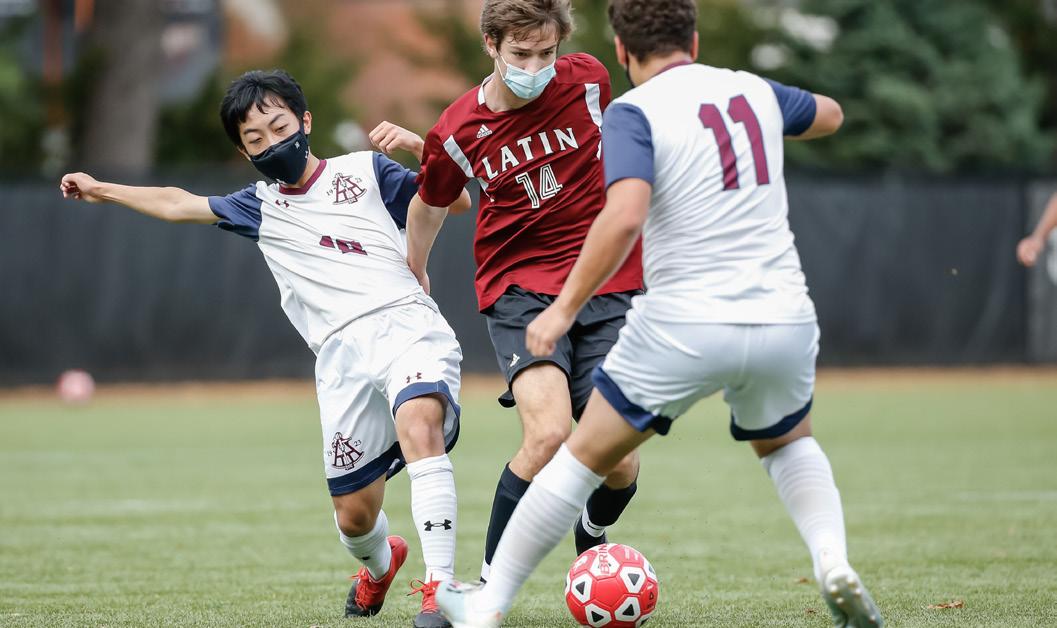

Varsity Soccer seniors (left to right): Brady Chappell, Miguel Rincon, Thomas Gaziano, Will Specht, Max Hutter, Ethan Chang, Alex Uek, Alex Fuqua, Byron Karlen, Peter Frates, Ben Brasher, Sam Morris-Kliment, Esteban Tarazona

Reflections on a Season Curtailed by COVID

by peter frates, varsity soccer co-captain, class i

This past soccer season was difficult and different, but I’m proud of our team for the way that we stayed positive, hopeful, and dedicated throughout the fall. Over the summer, Coach Sugg informed the team that we could not attend our preseason camp. This was one of the biggest disappointments of the year. Over the four-day stay each August at the Williston Northampton School, the team spends countless hours together, and improves quite a bit through both practices and games. From each of my four years, I have great memories of time spent with the boys at camp. As a captain last season, the time was crucial for getting to know the new players on the team, and building chemistry across all the grades. While this year was extremely different, the team’s level of commitment and hard work was not.

Instead of practicing and playing five days a week for almost two hours a day, the varsity team was allowed to practice on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, for an hour and a half. Knowing every minute we had on the field was a gift, there was a special energy at our practices this fall. Our coaches Sugg, Solís, and Thornton did an excellent job making the best of our limited time on the field. As a team, we are so grateful for the sacrifices that the coaching staff made to help make this season possible. Though the divided cohorts and grade level distinctions limited the number of players at each session, the coaching staff was innovative each week with new drills and games to keep practice at a high tempo. I found myself, as I expected, energized and excited to be going to school each day that we had practice, often waiting for the final bell to ring. One positive about the reduced days for practice was that on our two days off, we had ample time to work out on our own.

In mid-October, the team group chat was in a frenzy. We had just heard that two ISL teams were scheduled to play a game that weekend! Everyone was envious, and we all hoped for a way to get in on the action. Thanks to Mr. Teixeira and Mr. Brennan, we joined a small, five-school consortium of ISL teams to hold inter-school scrimmages on the weekends. This was a turning point in the year. From that point on, we practiced with a renewed sense of urgency, as we had the possibility of a game that weekend! In our final match, we beat a talented Belmont Hill team 1-0—an amazing way to end our RL soccer careers.

After the heartbreak of last year—when we were snubbed from the New England playoffs—we were disappointed this year not to have the opportunity to avenge ourselves. But, I am confident that the skill-based and tactical work that we put in this year will undoubtedly help the team follow the success of the 2019 team in the fall of 2021. //

Varsity Football seniors (left to right): Will Hyde, Beau Keough, James Gillespie, David D'Alessandro, Aaron Shlayen, Frankie Lonergan

How Do You Play Football in a Pandemic?

a season’s recap by head varsity coach mike tomaino

Football is unique in the sense that a large aspect of the game is contact—blocking and tackling. In many ways boys who play football enjoy those aspects of the sport, some may even yearn for the contact. It’s difficult to imagine a fall season without those key components of the game, but over the course of the fall, Roxbury Latin’s football team embraced new guidelines and continued to develop individually and collectively.

With the uncertainty of competition, and the strict nature of the cohort system, our challenge this fall became how to develop our athletes and also get better as a team. Furthermore, how would we do so with significantly less practice time? Our overall theme this fall was: Control the controllables. As a team we remained focused on putting forth a great attitude and great effort every day. We focused on becoming a faster, quicker, and more fit team with specific speed and agility drills. As we adhered to guidelines and worked to mitigate the spread of the virus, we began these drills completely distanced and individually. As competition became more likely, a new challenge presented itself: How do we continue to get better for the future, while fulfilling our athletes’ desire for competition? On top of that, how do we do so in a safe way? Our solution was to continue to incorporate the fitness aspect of practices, while adding in some individual skill work. Over time, we began to add more football-specific team activities, such as implementing and running our offensive and defensive playbook. Fortunately, we had some new students join us this fall, so this gave us an opportunity to introduce schemes to newcomers while serving as a refresher for returning players.

Toward the end of the fall, we were given the opportunity to compete against other schools, which was a relief for our athletes. At the end of the day, they love to compete, and while all the other stuff is important, playing in contests was at the forefront of their minds. Due to cohorts, our team was split into two “teams,” which presented a unique situation in which one of the cohorts had to have a “quarterback by committee.” Nevertheless, we played 7-on-7 games, which consisted of only skill position players—no pads, and only passing plays. Think of it as football without linemen and without contact—without blocking and tackling, the two major components of the game. While it wasn’t “real” football, it was competition and a step toward normalcy, which we all certainly appreciated. For our coaches and players, it was certainly a disjointed and unusual fall season, but as the theme went, we could only control how we reacted to the situation that was presented. Like our community members always do, we put our heads down and went to work. //

Be Both Tough and Tender

Headmaster Brennan Opens the Winter Term

Be Both Tough and Tender

I was outside the temple where the funeral of the beloved mother of one of my students had just taken place. I waited around to greet him. I was quite moved by the service. The mom was a wonderful person; she had long been separated from her sons’ father and had been battling cancer for the past six years. The boys’ remembrances of their mother were touching and especially meaningful given they in essence were signaling that she had taught them well, but that now they just had each other. I responded to my student with a hug and more tears. And he was crying, too.

This boy of 15 was a much admired scholar-athlete at his school. He exuded confidence and had been consistently elected to the presidency of his class. He had it all going for him. He was smart, personable, balanced, and a friend magnet. Throughout his young life, however, he recognized that his family structure was different from most other boys’. With an inattentive father, he was left to rely yet more than usual on the love and care of his mother. She was a ferocious protector of her three cubs. And now, she was gone. What would they do? What would he do? In fact, living among various relatives, he blazed through high school starring in three sports and earning honors grades. He went on to a prestigious college and is a successful man with a wonderful family of his own today.

“You cry, too?”

In fact, I do cry. Not always, but sometimes. And I always have. Thankfully I had parents and grandparents who didn’t mind shedding a tear acknowledging some overwhelming emotion. I am part Irish after all, and some say our bladders are located just behind our eyeballs! I cry when I am sad. I have cried when I was hurt or in awful pain. But I also cry when I am overwhelmed with joy. When someone I care deeply about does something extraordinarily kind. Or expresses love for me. I also have cried when I am overwhelmed with something that is exquisitely beautiful. Thankfully I am not riddled with the question that I believe

too many people are, especially too many men, and that is “Should I cry?” “What will people think of me if I do?” “Will I appear weak if I cry?”

Today I am using crying as a pointed example of feeling, and expressing feeling. How often we have been in situations in which we find ourselves wanting for words. It’s cliché, I suppose, to say that words are inadequate, and sometimes they are. One of our goals as a school is to teach you how to find the words to describe what is true and deserves to be said. But sometimes even the specific, powerful words we teach you are not up to the task. Sometimes what we think, and, especially, what we feel cannot be captured in words. Since humans have roamed the earth they have searched valiantly for ways in which to express themselves. Sometimes with words—spoken, printed in books, attached to valentines, or scrawled on cave walls. But other times with expressions, with hearty laughter, or hugs and kisses, or even by striking someone. Playwrights and novelists and composers and poets have left us with countless reverberating evocations of their feelings. Shocking. Inspiring. Reassuring. Provoking. Affirming.

Many works of art are intended to move us, to find the spot deep within in which feeling resonates. As I get older that place often has to do with days gone by, and places I have loved, and people I have loved who are now gone. Smells. Tastes. Sounds. I want to be open to those sensations. They remind me of remarkable people. Of remarkable times and places. They remind me of my younger self. They remind me I was loved. They strike a nerve. They remind me I can be tender.

Often the rhetoric of our school goes whizzing by. Uttered but not felt. Today I want to pause on a phrase that can be found in our publications and on our website, but on which we rarely dwell. I say it when we are hosting prospective students and their parents at open houses. Others of us utter it, too, as we describe our school: “We want our boys to be tough and tender.” Tough and tender. Today I shall dwell on that unlikely pair.

An Exemplar

Several years ago there was a boy in the school who ended up being quite memorable. Through the admission process we knew that he was poorly prepared for the academic rigors of RL. He had had an unfortunate start to his life with a dysfunctional family and schooling to that point that had neither taught him all he should know at his age or demanded much of him. But as we got to know him, we saw something special in him. A spark. Desire. Openness. We accepted him and the boy could not be happier. He had no idea what he was in for.

The happiness the boy felt in anticipation of his starting RL dissipated on about the second day of school when he realized he was clueless about how to do the kind of school that RL was demanding of him. He had never done a minute of homework in his life; his classmates at his old school couldn't care less

for what they were all doing; and he had never felt stretched, challenged, inspired, or, for that matter, affirmed. At RL, all that changed. The work rolled over him relentlessly. He didn’t know how to start. He couldn’t put three sentences together. Kids’ hands were flying up in every class while he was still trying to understand what the teacher had asked. He got the sense that everybody else knew the inside secret. And that he was an outsider, woefully unprepared for this assault. He was bloodied.

Every report meeting which the faculty holds at the end of each marking period, this boy was discussed. Some faculty rolled their eyes. Others explained all they had done to help this boy to succeed. His advisor reported on what he had tried. Everyone knew that this boy was unlikely to make it. He was over his head. And despite all the extra help—tutoring with each of his teachers and with older boys every free period and after sports—there was a feeling that this poor boy would grow weary and, understandably, give up. The first two summers he was at RL were booked with all kinds of extra support—summer school and more tutoring. This boy had hardly a minute to play. To hang out with the kids in the neighborhood. To bolster his reputation among a different group that he also cared about.

At several points along the way, the adults who wanted him to succeed so badly wondered if they were in fact acting cruelly toward this poor kid. Someone who had been involved in the admission process asked if the “spark” that had been seen early on was, in fact, being snuffed out. Another teacher said, “I submit that it is burning brighter than ever. This kid wants it. He’s tough.”

He was tough all right. With no academic role models at home, he was flying blind. But he was determined not to squander the chance he had been given. He was determined to make up for his previous seven years of school in which he was asked to do little. He was determined to put himself in a position to take advantage of all that RL had to offer— including setting him up for a very different life from the ones members of his family had available to them for generations. Round about Class IV, the D’s and C-minuses began to disappear from his report card. He emerged as one of his class’s best athletes. And he decided to try a few more things— debate, Glee Club, theater. Some worried that he would be needlessly distracted. In fact, he became more organized, more energized. In each of those areas, this boy’s potential began to emerge. He was tough. He could do it. By the time this boy was a senior, he had amassed an all-honors record and was a leader of various aspects of school life. He was tough all right. We asked a lot of him. We did not give up on him. More important, he did not give up on himself. And whatever we asked of him, he asked more.

Tough Guise

When I was growing up, back in the Dark Ages of the mid-20th century, we had plenty of role models for what it meant to be tough. I loved a TV show called The Untouchables, which chronicled the lives of gangsters and their inevitable demise at the hands of astute, earnest, good-looking FBI agents. The gangsters—part of what I later learned was an extensive, intricate network of crime families throughout the U.S. called the Mafia— were unattractive human beings; they were ruthless killers, not seeming to mind destroying who or what got in the path of their seizing for themselves whatever it was they wanted. They were ceaselessly self-interested. The allegory of the gangster morphed into something different when The Godfather movies came along. In these film classics the Corleone family was portrayed as three-dimensional, with characters who went about their sinister business in subtler, more sophisticated ways. Often the dirty work was accomplished by underlings while the leaders of the extended family “kept their hands clean,” although one always had the idea that any one of the most effective leaders could at a moment’s notice resort to a more primitive self in which he effectively, violently and physically could do in, likely kill, an adversary. Last year, another wonderful movie appeared, The Irishman, in which the great Robert DeNiro, through his character, reminds us that well into the 20th century an underclass of people benefitted from their intimidation of more upstanding types.

What the more modern depictions of these gangster characters showed was that they were not just tough. They were also human, and to be human meant that they had feelings, that they cared about particular other people (usually their own family members), and that when they harmed, or even killed, they were sometimes capable of remorse. Masculinity, the essence of being a man, however, was always defined by being a certain kind of tough. It seems quaint or

even absurd now to be reminded of the role models we had in the mid-20th century. I can talk about them because they constituted many of my cultural, public reference points. The pervasive sense of what it meant to be a man in those days had to do with physical capability—to be athletic or strong was even better, as was a capacity for tolerating pain, and never showing emotion or feelings. Men were judged by what they did, not usually by what they thought or felt. Of course, there were public figures, Presidents or other elected officials, as well as certain prominent intellectuals, teachers and writers who were respected for their ideas and capacity to reason and to wield language, but they, too, usually did not convey emotion or betray any weakness. It goes without saying that most of these role models were also white, of European origins, and straight. That of course was the ideal, and those who were not those things felt even more challenged.

The George Bailey Man