28 minute read

PHOTO PORTFOLIO

a photo portfolio

Advertisement

Above: A greenhouse frog drawn into the open by passing rains in the Exuma Cays. Right: Storm over the mooring field near the park headquarters. Moorings prevent the repeated tearing up of the sea bed caused by anchoring, and also provide and safe and secure way for boaters to pass the night. But most importantly, the modest mooring fees form a large part of the park’s operating budget and enable the park to continue functioning and protecting this amazing ecosystem. Bottom right: Light from one of the holes in the ceiling of the insanely awesome Thunderball Grotto in the Exumas.

Above: Virtually every afternoon in the Exumas, rising columns of warm air build massive cumulous clouds. It’s like an enormous mountain range that changes every day. Left: Schooling fusiliers just beneath the surface during a torrential rain storm in Raja Ampat, West Papua. Below: The now famous swimming pigs of The Bahamas. Enough said.

SWIMMING WITH WHALES

By Colin Ruggiero

Swimming with whales is always such an incredible experience. One time, when I was headed to a nearby island in the southern Sea of Cortez, we noticed that there was a tremendous amount of feeding activity happening and there were lots of whales in the area. I haven’t had a lot of luck just coming up on whales in the boat and jumping in to swim with them in areas where they’re not accustomed to people: and I can’t say that I recommend people do that—for the whale’s safety or their own—but I jumped in just to get a sense of what was happening. Following feeding action like that with a boat always leaves you two steps behind, and so I just got in the water and had the boat back off and leave me there to see what might come around. There was so much activity in the area, and it wouldn’t be long before I saw birds headed my way. Under the surface, the first thing I would usually see was a big school of jacks leading the charge. Right behind them would come the mobula rays, and when that happened, I knew there was likely a whale nearby as well. It was difficult because you’re swimming hard to try to follow or just get a little closer to the animals and so you’re always out of breath and it’s hard to dive very deep. The water is absolutely full of krill and when you look into the light, the backlit krill are like a wall and you can’t see anything at all. When you look down the light rays are just dizzying in the deep water and it’s hard not to get a sense of vertigo bobbing around out there.

At one point an open-mouth humpback emerged out of nowhere. It saw me and slapped its tail in a sharp turn, veering away from me. I figured that I had startled it, but I turned around, and out of the light rays emerged an adult fin whale and her calf just moving through like a train about 30 feet below me. Just so special. Eventually though, I realized that it wasn’t a great idea to be a slow, awkward monkey floating around in all of that commotion like that. All of the other creatures could easily get out of the way of the feeding whales and there was too much motion in the water and bubbles and fish scales and krill and light for the whales or I to really keep track of each other. So I got out and flew my drone and got some amazing aerial images as well. A gray whale rolls onto its side for a better look. It’s hard to deny the recognition taking place in another intelligent animal when a whale looks at you from this distance.

s the saying goes, the squeaky wheel gets the grease. Back in the old days, the only fishermen who made noise came from the commercial fishing sector. Sportfishermen had no voice because we were just a bunch of happy-go-lucky anglers scattered about the nation enjoying a bountiful catch. Recreational anglers were not organized because we did not have to be. There was little reason to squeak. However, in the past few decades, as pressure on the fishery has increased the sportfishing community has come together. We have asserted ourselves with lawmakers and have simply asked to be treated equally.

Today, the most influential voice for our fishing community is from the American Sportfishing Association. The ASA, and other vital groups have been able to get the message out to lawmakers that sportfishing has a massive impact on the American economy. We create millions of jobs from the local marina dockhand up to the CEO of Viking Yachts. Boat sales, gear sales, charter boats, fishing travel and even this magazine, all add up billions of dollars to fuel a massive economic engine. And that engine is running on high test.

In the following pages, we examine several of the most pressing issues facing our angling community and the efforts organizations like ASA have undertaken, such as trying to build the fishing population to 60 million anglers in the next 60 months, and helping to navigate the treacherous clashes between state and federal fishing laws and lawmakers.

It would be awesome if we didn’t need the groups like the ASA. That is, if our elected officials actually went to the capital to serve the best interest of the people who elected them. Unfortunately, that reality does not always exist. At least not in this solar system. Thankfully, we have advocacy groups who have learned how to squeak quite loudly and where we need the grease.

BY LIZ OGILVIE

Have you ever thought long and hard about your experience crossing a state line? Probably not. You drive down the highway and there is no dotted line indicating the border and no welcome party to greet you. You first pass an insignificant sign that matter-of-factly states that you’re leaving one state and entering another. But then, just a few yards down the road, is a billboard-sized announcement that you’ve arrived, complete with everything from state slogans to the current governor. “Welcome to Georgia. The state of adventure!” It makes you want to stop at the next farm stand to pick up a basket of fresh peaches.

And you might notice some differences as you progress into new territory. The maximum speed limit may reduce from 65 to 55 miles per hour. The roads may be riddled with potholes one minute, then be newly paved with freshly painted lines the next minute. There might even be more speed traps. It’s pretty obvious where the tax dollars are being spent.

There’s a second type of state boundary. This one is also invisible, but is only crossable by watercraft. It’s the line several miles off a coastal state’s shores. When you cross over the line, you either head into another state’s waters or into the vast ocean territory surrounding our country that is federally managed.

Most people wouldn’t notice. Unlike our highway system, there’s no signal out on the open ocean that you’re navigating from waters regulated by states to those managed by the federal government. There’s no sign announcing your arrival, no welcome message, nor anything enticing you to stay. You simply keep on boating. But if you’re a recreational fisherman on that boat, there are often major differences in the can and can’t do’s on one side of that line versus the other.

A World Apart

There’s a philosophy chasm between state and federal management of our marine fisheries. Does it involve money? Absolutely. Is conservation a factor? You bet. But an often-overlooked ideology is that “recreational angler” equals “partner.”

Most American anglers would agree: freshwater fisheries management has largely been figured out. Without a doubt, there are still several challenges to conservation and access that are unlikely to change anytime soon, but from a purely management standpoint, state fish and wildlife agencies are working hard to ensure resident and visiting anglers have reasonable access to healthy fish stocks. And, in general, the federal government is not involved.

This is where the money comes in. States and the recreation community have a symbiotic relationship, due in part to the agencies’ funding model. Most, if not all, of their fisheries management budgets come directly from anglers. It’s doled out from a collection of funds made up from fishing license fees and excise taxes on fishing equipment and motor boat fuel. That fund totals about $1.7 billion per year.

Let’s say that again. A total of 1.7 billion per year is collected from sport fishermen—us— which is spent on fishery management.

But the relationship between state agencies and the recreational fishing community is far from just a dollars and cents transaction. Agencies, in both the fresh and saltwater areas they manage, see anglers as part of the conservation solution. They solicit public input on management decisions and work with their communities to ensure anglers are satisfied with their experiences on the water.

Similar close connections exist with many of the federal land management agencies, such as the U.S. Forest Service, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Bureau of Land Management and the National Park Service. These agencies welcome millions of visitors every year onto the public lands they are the stewards of, many of whom are casting a line. Do we have occasional disagreements over management decisions? Sure. But in general, these agencies view recreational anglers as contributors to their conservation agenda, even though their federal budgets are not fueled by direct funding from in-state fishing expenditures.

The third management system recreational anglers contend with is when they cross that invisible line from state to federally managed marine fisheries, which, for most parts of the country, extend from three to 200 miles offshore. However, in the Gulf of Mexico, all five states—Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas—have pushed state waters out to nine miles. The federal waters are managed by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) under the auspices of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Other familiar NOAA programs are the National Weather Service, the Satellite and Information Service, and the Marine Sanctuaries division. They’re also the folks who create and continuously update your marine maps, which get loaded into your navigation systems. (If you ever get lost, don’t blame them.)

A consistent and unique challenge for NMFS has been balancing fisheries used for both recreational and commercial purposes. The state boundaries were set to three miles offshore with the establishment of the Submerged Lands Act of 1953. Further, the 1976 Fishery Conservation and Management Act established federal waters from where state boundaries end out to 200 miles offshore, protecting U.S. waters from extreme harvest by foreign commercial fishing fleets. Two decades later, because many marine stocks were still declining, the law was amended with provisions to end overfishing by our own commercial industry. This became the 1996 Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSA). Once again, a turning point in the marine management strategy that was mandated by the federal government and has had lasting benefits.

The first time the federal government started paying attention to commercial activity in our oceans was in 1871, when President Ulysses S. Grant established the U.S. Fish Commission. For the first time, they were to report to and advise Congress on what harvest activities were taking place and if protection of the resource was needed.

Through the years, with the continued morphing of the agency, the focus remained on commercial activity. Up through the 1970s, it was even called the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries. Many anglers today still hold the perception that the NMFS only understands and cares about commercial fishing, and a new authorization of MSA would help address the challenges of a constrained management approach (see article on page 62).

Access to outdoor recreational activity is a priority to many Americans, and fishing access is no exception. Advances in technology in gear and transportation extend the possibilities for where we can fish and how often. We can make a daytrip out of going to The Bahamas from Miami and back. Whether you stay in state waters or go those extra few miles, knowing who is managing your day on the water and what their priorities are is key to making recreational anglers partners in the decision-making process. Just don’t be on the lookout for any welcome billboards posted in the middle of the ocean any time soon.

Liz Ogilvie is the Chief Marketing Officer for the American Sportfishing Association.

Recreation and Regulation

BY MIKE LEONARD

Left: Senator Ted Stevens (R-AK) and Senator Warren Magnuson (D-WA) during hearings on the 200-mile fisheries legislation (later the Magnuson-Stevens Act) before the Senate Commerce Subcommittee on Oceans and Atmosphere in Washington D.C., on December 6, 1973. Photo courtesy of Stevens Foundation.

Most anglers don’t spend a ton of time dwelling on fishing regulations, much less the underlying regulatory process and statutes that lead to them. We know the season dates, bag and size limits and any other potential regulations, and we go!

After all, fishing is a way to get away from the more tedious and mentallytaxing parts of life. Trying to understand the complicated scientific, legal, and political factors that go into determining when and how you can go fishing isn’t exactly a relaxing pastime.

But for those of us who do spend a lot of time focused on fisheries policy—an admittedly small group—we’re in the middle of an extremely important and exciting time, particularly for the future of how offshore fisheries are managed.

The Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSA), named after influential Senators Warren Magnuson from Washington and Ted Stevens from Alaska, is going through the process of being reauthorized by Congress. Originally passed in 1976, MSA is the primary statute governing how federal marine fisheries are managed.

For the first time in its history, the topic of how MSA addresses recreational fishing is leading the debate. This is encouraging news for the millions of anglers and recreational fishing-dependent businesses who have felt like recreational fishing was an afterthought in a law and management system that has, for decades, focused almost entirely on commercial fishing.

The Histor y of MSA

The world in 1976 was very different than the one we live in today (no cell phones or texting!), and marine fisheries management is no exception. Overfishing off the U.S. coast was rampant, particularly from foreign commercial vessels, resulting in U.S. fisheries that were in pretty poor shape. In response, U.S. territorial waters were expanded out to 200 miles and a framework was created for managing the domestic fishing fleet. Eight regional fishery management councils, comprised largely of fishermen, were created to develop fishing regulations.

While the original MSA was successful in kicking foreign vessels out of U.S. waters, it wasn’t as successful in sustainably managing our own. As a result, overfishing remained a significant problem for fisheries throughout the nation, hurting not only the health of fish stocks and habitat, but also many coastal communities.

Major changes to the law were made in 1996, with a significant focus on preventing overfishing and setting firm deadlines for rebuilding overfished fisheries. The next major reauthorization took place in 2006, in which further efforts to promote resource sustainability, including the requirement that all federally-managed fish stocks have an annual catch limit, were added.

The good news is that, thanks to MSA and the changes that have been made to it over time, the U.S. has arguably the best managed commercial fisheries in the world. Overfishing is now at an all-time low. However, because MSA’s focus has been almost entirely on managing commercial fishing, which is a very different activity than recreational fishing, in many cases, recreational fishermen have not reaped the benefits of MSA’s biological successes.

The commercial fishing-oriented management approaches prescribed by MSA require precise and up-to-date biological and harvest data, both of which are lacking for many recreational fisheries. As a result, anglers pursuing stocks like summer flounder, cobia, black sea bass, triggerfish, amberjack, red snapper and others have faced access restrictions that change wildly from year-to-year and don’t seem to reflect what anglers are experiencing on the water. Despite overfishing being at an all-time low, angler frustration with federal fisheries management has reached an all-time high.

As Congress once against looks to reauthorize MSA, the recreational fishing community has made it a top priority to ensure that this MSA reauthorization is finally the time in which recreational fisheries management issues are sufficiently addressed separately from that of commercial fishing.

The Modern Fish Act

In July, 2017, six U.S. senators, led by Roger Wicker (R-Miss.) and Bill Nelson (D-Fla.), introduced S. 1520, the Modernizing Recreational Fisheries Management Act (Modern Fish Act). This bipartisan bill addresses the recreational fishing community’s priorities for improving MSA in a way that finally accounts for the importance and uniqueness of saltwater recreational fishing. A similar bill, H.R. 2023, was introduced in the House earlier in the year by Representatives Garret Graves (R-La.), Gene Green (D-Texas), Daniel Webster (R-Fla.) and Rob Wittman (R-Va.).

The Modern Fish Act is essentially a bundle of various management and data collection reforms that cumulatively will adapt the federal marine fisheries management system to better align with the nature of recreational fishing. Most of the provisions stem from a landmark report released in 2014 by the Commission on Saltwater Recreational Fisheries Management (also known as the Morris-Deal Commission, after co-chairs Johnny Morris, founder and CEO of Bass Pro Shops, and Scott Deal, president of Maverick Boats) titled “A Vision for Managing America’s Saltwater Recreational Fisheries.”

Some of the most notable provisions of the Modern Fish Act include:

Improving angler harvest data by requiring federal managers to explore other data sources that have tremendous potential to improve the accuracy and timeliness of harvest estimates, such as state-led programs and electronic reporting (e.g., through smartphone apps).

Requiring fisheries managers to finally provide a long-overdue review of how fishing quotas for individual species are divided between the recreational and commercial sectors. Rather than being based on decades-old decisions, the Modern Fish Act would establish clear, objective criteria upon which these decisions could be based, and require periodic review to ensure these allocations are working.

Recognizing that recreational fishing needs to be managed differently than commercial fishing. Even though recreational and commercial fishing are fundamentally different, they are basically managed the same way at the federal level. The Modern Fish Act will authorize NOAA to use management strategies that have been successful at the state level for managing recreational fishing.

A Broad Coalition of Support

Anyone who has spent much time working with recreational fishermen knows that if you ask a group of 10 anglers their opinion on something, you’ll get 20 different responses. But in the case of the Modern Fish Act, the recreational fishing and boating community is pretty well united. Every major national recreational fishing and boating organization working on saltwater fisheries issues support this bill.

The coalition of groups supporting the Modern Fish Act includes: the American Sportfishing Association, Center for Sportfishing Policy, Coastal Conservation Association, Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation, Guy Harvey Ocean Foundation, International Game Fish Association, National Marine Manufacturers Association, Recreational Fishing Alliance, The Billfish Foundation and Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership.

Between the broad support for the Modern Fish Act within Congress and among the recreational fishing and boating community, the prospects are promising that this bill will move forward either as a standalone bill or as part of a broader MSA reauthorization. However, it’s important that anglers continue to weigh in with their members of Congress and urge their support. You can visit www.KeepAmericaFishing.org to learn more about the Modern Fish Act, get involved and stay up to date on this and other issues affecting the future of our sport.

Mike Leonard is the Conservation Director for the American Sportfishing Association.

SIXTY in SIXTY

BY NICK HONACHEFSKY

It’s the first rule of survival—procreation. Survival is not only limited to biological creatures, but can apply to movements, passions and philosophies as well. Fishing is in my blood, always has been. I can’t even imagine a hundred years from now that people won’t have the passion or drive to go out fishing. It’s a legacy we all share in a common bond. As anglers, if we want to see our sport thrive and continue to have power and presence in an ever-changing human environment, we need to ensure that our “species” of anglers and the passion of fishing survives onward into future generations.

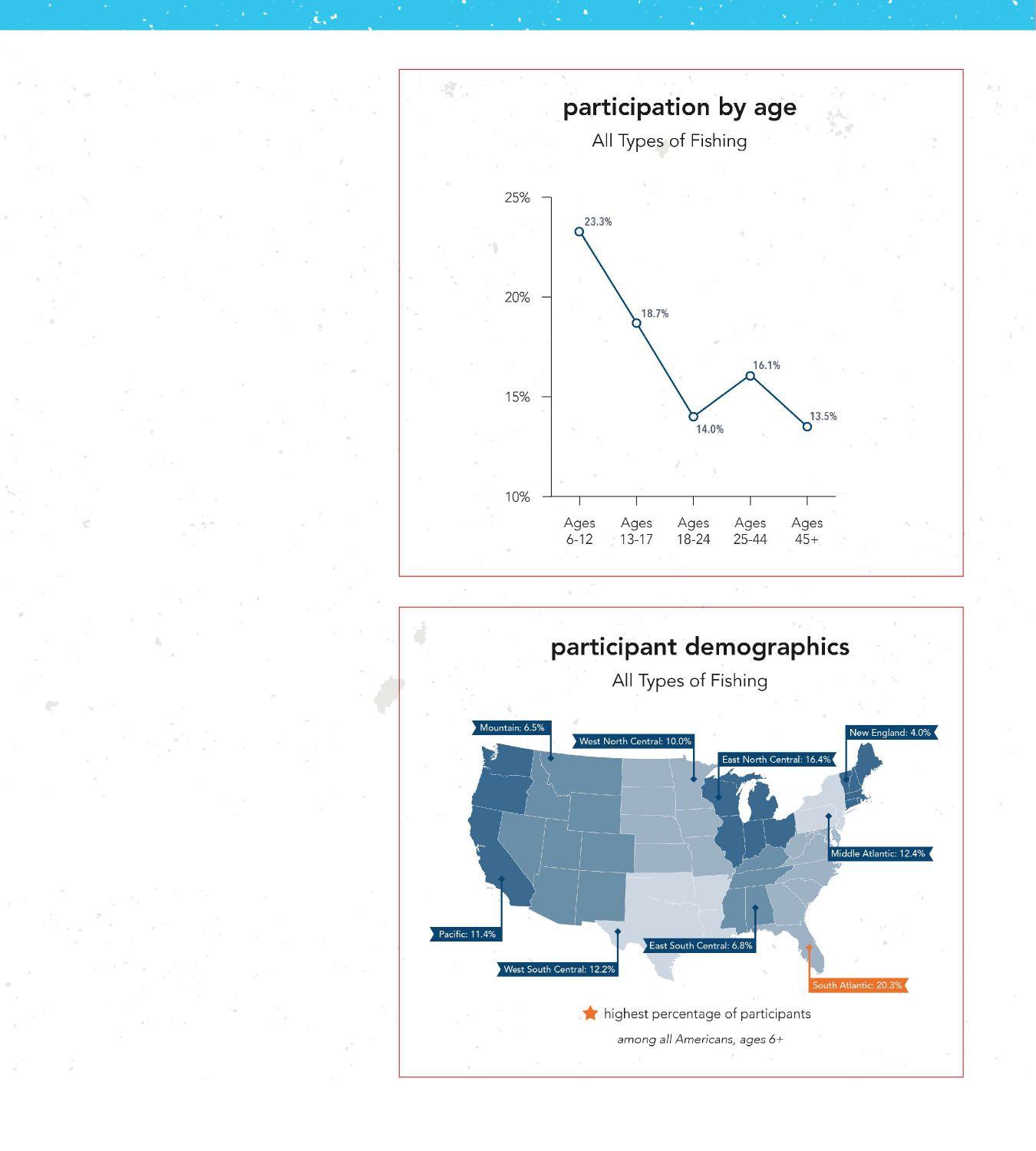

Graph courtesy of the Recreational Boating & Fishing Foundation (RBFF)

he Recreational Boating and Fishing Foundation (RBFF) recognized

Tthe importance of keeping our “stocks” high and engaged and developed a plan, termed “60 in 60.” The acronym refers to a program started on April 1, 2016, aimed to sustain a community of 60 million anglers within 60 months in the U.S. The real message and power of the 60 in 60 program is that by reaching a goal of 60 million anglers, the results could translate into 14 million new anglers contributing $35 billion to the economy, 7.5 million new boaters contributing $10 billion in economic contributions and newly-generated $500 million in fishing license revenue. Over a series of instituted programs and partnerships, the overall benefits of the 60 in 60 program include: increased fishing license sales and boating registrations; a huge bump in tackle and equipment sales; an expanding customer base for businesses; and more funds for states to protect aquatic natural resources through fish stocking, habitat management, fish surveys and boat ramp management.

The RBFF’s working mechanism to build the structure of achieving the lofty 60 in 60 goal is termed the “R3” methodology, or Recruit, Retain and Reactivate, namely recruiting new anglers, retaining the active anglers and reactivating any anglers who may have slipped off the radar.

“Through the R3 program, we provide grants to state agencies and communities to build the programs that benefit fishing communities,” states David Rodgers, communications manager for the RBFF. Two recent examples of states benefitting from the program are Vermont, which has instituted the “Reel Fun in Vermont” push utilizing web, print, radio and social media to increase angler participation, while the Nebraska Games and Parks Commission will engage in sending timely and targeted emails to encourage multi-year license renewals and boat registration renewals.

Out of all the R3 goals, recruitment, is the hardest nut to crack. “We really try to focus on recruitment as that’s where we get the most resistance,” explains Rodgers. “Those we retain and reactivate are already engaged and know the experience, but in recruitment efforts, we provide resources to help introduce prospective anglers to fishing.” Examples of recruitment include the RBFF’s recent partnership with Disney to represent the RBFF brand at the Disney resorts to introduce people to fishing, as well as running “First Catch Centers” across the country. “The First Catch Centers are like Little League and Pop Warner football programs, attracting kids to participate like feeder programs into the sport of fishing,” notes Rodgers. “Hopefully, the First Catch initiative will be our Little League or Pop Warner to get kids involved and committed to fishing.”

The RBFF’s 60 in 60 program also has stand-alone initiatives as well, and as Rodgers states, “In 2018, we are setting out to develop two new programs working with Fishing Future in Texas and Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commissions. The idea is to provide curriculum and draw people with limited or no fishing experience into a series of events to learn about fishing in the area (e.g., rigging

up rod and reel, learning the nearby waters, boating information).” Rodgers understands that while later generation adults may have had parental influence to get involved in fishing, there are many kids and adults alike that may have not had that push to move into fishing. “We want to create lifelong participants. These programs are centered a lot around urban kids who may have both parents working and never have an opportunity to get introduced to the sport. We step in to be the mentor to go fishing, and go fishing often.”

So, what does the future hold for the 60 in 60 program? “Whether we reach the goal or not, we want the industry to rally behind the idea and see a concerted effort between state agencies and industry-related corporations to move the needle, to have fishing businesses rethink their focus on entry level customers,” said Rodgers. “If we realize the success we expect of this initiative, after this program, we should hopefully have built 10 more years of new customers to sell to. This is all a rallying cry for the industry and corporations to get behind recruiting new members; it’s good not only for the bottom line of profits but more importantly to ignite humanity for our passion and building numbers of fishermen as a whole.”

Any time we can grow numbers for supporting the sportfishing lifestyle with engagement, conservation and protection of resources, we all win. Help spread the 60 in 60 ideology on your own on a grass roots level. If you see someone who doesn’t have the means or wherewithal to get on a boat, take them out fishing on your next trip. If your kid’s friend has a family that works day and night and has no time to teach them, bring them along the next time you head out with your kid. 60 in 60 is taking off across the country. It’s a focused movement that has been a long time coming. Even one small gesture can make a world of change. Join in the mantra of the RBFF’s 60 in 60 campaign and become an ambassador to the fishing world.

Nick Honachefsky is a Contributing Editor for Guy Harvey Magazine and the host of the new video series, Saltwater Underground. Top and bottom graphs courtesy of the Recreational Boating & Fishing Foundation (RBFF)

This is proven by the fact that most of Jesus’s disciples were fishermen. If you didn’t know that, I will attempt to enlighten you. Scholars may disagree on the exact number, but most believe that at least five of the 12 apostles fished for a living. Other historians raise that number to seven. So, in any case, approximately 50% or more of the inner circle netted fish for a living. That puts you and me in pretty good company.

It may be logical to assume that fishing was an extremely popular profession during the time of Jesus and the rule of the Roman empire. In fact, it wasn’t. Sure, the folks around the Sea of Galilee did a lot of fishing, but in general, most people of that era were shepherds or farmers. Sheeps and goats were a lot easier to round up than catfish, which were (and still are) common to the Sea of Galilee. Sidenote dear reader: the Sea of Galilee is not really a sea at all. In fact, it’s a lake commonly known as Lake Tiberias or Lake Galilee. At 600 feet below sea level, it is the lowest freshwater lake on Earth, and the second lowest lake in the world after the Dead Sea, which is a saltwater lake. With 30 miles of shoreline, Lake Galilee is fairly large, which may be why they called it a sea. It’s a total of 64 square miles in area and 13 miles long and about seven miles wide.

At any rate, in addition to herding sheep and tending to farm animals, there were many professions to pursue 2,000 years ago, as there are today, even if we don’t count IT professionals and social media influencers. There were laborers, craftsmen, politicians, military personnel, musicians, tax collectors, a very large population of slaves, and a small smattering of fishermen.

So, is it just an anomaly that Jesus attracted fishermen to follow him? Was it just coincidence that these hard working men put down their nets and decided to dedicate their lives to a new and uncertain future? Maybe it’s that fishing itself is an act of faith. We venture out into the wilderness with our rods, reels and consciousness of pure hope—not knowing whether we’ll come home empty handed or with a cooler full of keepers. We dig in our tackle box with great care wondering if our choice of lure is correct. We gaze out across the water and try to divine what patch might hold a few fish. Many of us even say a little prayer as we rare back and chuck the lure as far as we can. “Please God, can you please just convince a big ol’ speckled trout to bite my hook? Please Lord?”

Of course, I must point out here that in those olden days, they didn’t have rods and reels and lures and bass boats and fancy marine electronics because, of course, none of that gear had been invented. Fishing was hard labor and performed with nets that had to be mended and cleaned and protected. Fishermen often worked long into the night, using two primary types of nets. Circular cast nets, similar to what we use today, were abundant. They generally stretched about 15 feet in diameter with fine mesh for catching fish in shallow water. Folks would toss cast nets from the shore or from the boat near shore. In deeper water—Lake Galilee is 141 feet deep—they used drag nets, some more than 300 feet long and eight feet wide, similar to today’s shrimp trawls. Perhaps the faith and work ethic of fishermen is what drew Jesus to them and them to Jesus. Fishing also provided the prophet with so many perfect analogies, such as “the kingdom of heaven is like a dragnet cast into the sea, and gathering fish of every kind.” And, “you should be fishers of men.”

Also, fishing was a source of some outstanding Biblical stories, the most famous of which is when the disciples weren’t catching anything until Jesus appeared and told them to try the other side of the boat. Then they caught so many the net almost ripped apart. So, it could be accurately claimed that Jesus was the first fishing guide. I know a lot of guides, but I’m pretty sure I’d pick Jesus every time.

I love the way that story begins, as if it’s you and your buddy sitting around on the porch wondering what to do. It goes like this:

Simon Peter said to them, “I am going fishing.” And they said to him, “We will also come with you.” Yep, I’ve been there. Of course, among me and my fishing disciples, the next sentence would have been: And they asked him, “Who shall be bringing the wine?”

Even with all of the love and respect for fishermen, there were challenges for Jesus and his fisher followers. First of all, the Philistines controlled most of the coastal area around the lake, so the Israelites were not able to access fishing as readily as they might have liked. Plus, according to the Law of Moses, the Israelite people were not supposed to eat fish unless they had scales. So the abundant and aggressive catfish in the lake were forbidden to eat. Yet, we know from the story that someone caught at least two fish from Lake Galilee near the city of Bethsaida and then they fed 5,000 people. Surely that was a miracle, or the most amazing fish tale I’ve ever heard.

Historians also report that the fish was a favorite image for Jesus because the Greek word for fish (ichthus) consists of the first letters that describe who Jesus was: Ihsous, CHristos, THeos, Uios, Swthr which means Jesus, Christ, of God, the Son, Savior and adds one more reason why Jesus loved fishermen.

In case you’re wondering who of the 12 were fishermen, they were Simon, Peter, Andrew, James and John and probably Thomas and Bartholomew. Definitely not Judas.

Those of us who have a deep love and passion for fishing really do consider it a religious experience. That sentiment is probably best described by the simple poem known as The Fisherman’s Prayer:

I pray that I may live to fish Until my dying day. And when it comes to my last cast, I then most humbly pray: When in the Lord’s great landing net And peacefully asleep That in His mercy I be judged Big enough to keep.