5 minute read

When You Think You Have Seen It All… Think Again

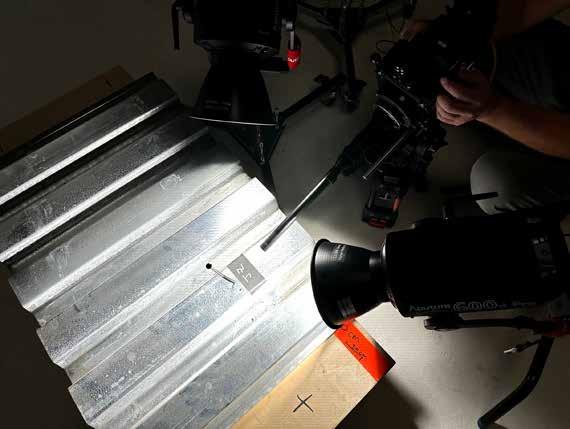

Approximately a month after Hurricane Ian made landfall on the southwest coast of Florida, I received a group email from the Roofing Industry Committee on Weather Issues (RICOWI). The email included some recent roof observation photos submitted by Ron Kough, RRO of Roof Assessment Specialists, Inc. Ron’s email had a picture attached that tested my ability to comprehend what I was seeing. A similar image is shown at the bottom of page 14.

It was from a mid-rise condominium on the Gulf Coast in Sarasota County. It is approximately 50 miles north of the location where Ian made landfall. The sustained wind speeds in this area were reported to have been between 70 to 80 mph. These wind speeds were substantially below design wind speeds required in recent versions of ASCE 7 for this structure. But what caught my attention was not that this roof covering was damaged but the particular way the fasteners had penetrated the roof covering. It was reminiscent of a bed of nails that we have all seen before. This condition was present in several roof areas.

I have seen many roof coverings in my time where fasteners have become disengaged from the roof deck after a high-wind event, particularly when they are installed over lightweight insulating concrete decks (LWIC). Usually, the fasteners can be felt under the roof covering where the fastener didn’t go back into the deck after experiencing roof covering uplift. Rarely, the head of the fastener will protrude through the covering. What made this situation different was that the point of the fasteners was pointing upward! That was something that I had never seen.

Ron is a very knowledgeable roof consultant and an FRSA associate member who I’ve known for some time now, so I reached out to him to discuss his findings. He filled me in and asked if I would be interested in joining him to observe him making some roof cuts. With many of my questions still unanswered, I jumped at the chance to see for myself what had caused this very odd situation.

We knew that the roof assembly was a structural concrete deck with an LWIC fill placed over the structural concrete. The visible roof covering was a modified bitumen membrane with a white roof coating applied. Protruding through the roof were what appeared to be 16d smooth shank nails. The first cut revealed that the upper modified membrane was not bonded to the underlying membrane. That may have been due to the presence of aluminum coating on the underlying roof covering. What appeared to be a feeble attempt to torch-apply the upper membrane to the underlying roof covering made removal very easy. Between the two membranes were a number of threeinch plates with a 1/4-inch hole in the center and three evenly spaced 3/16-inch holes closer to the perimeter. Some were still placed over the underlying roof covering in their original location, with three of the 16d nails driven through the underlying roof covering and into the LWIC. Other plates and nails were lying loose between the membranes while others were upside down and protruding through the upper roof covering.

So, we now knew what the fasteners were, but still the question remained as to how the fasteners became disengaged from the deck and had the space to flip over 180 degrees. The underlying roof covering had an organic sheet mechanically attached with LWIC fasteners that were fairly sparce, at least in the test cut location. The organic base sheet which looked like #15 felt had pulled over the fasteners, leaving only the aforementioned plates and 16d nails attempting to hold the underlying roof covering to the deck. Since the 16d smooth shank nails offer little pull-out resistance in a LWIC deck, they had easily pulled out. That means that the underlying roof covering had to be up at least three inches above the deck during the high winds. But to allow enough space for the fasteners to pull out and then scatter and overturn between the two roof coverings, the upper roof covering had to have at least a similar space. Picture the two roofs floating independently above the deck as the wind exerted negative pressure on the roof coverings. The fasteners were being hurled into the void by the underlying roof covering as it buffeted or fluttered during the event. Some of them had landed plate down and point up (think of dropping a hand full of cap nails). When the wind decreased and gravity caused the roof coverings to lay back down, the fasteners penetrated the upper roof covering, causing the effect that had initially gotten my attention.

We all know that roofs can blow off during high-wind events, but hopefully this situation helps one understand some of the dynamics at play. I don’t know the age of these roof coverings or what editions of the building codes were in place during their installation. For the purpose of this article that is not important, however, contractors need to be aware of current code requirements concerning recovering and replacement. Specifically, item 5 in the section on page 16 clarifies that if an existing roof is used for attachment of a new roof system, then the combined system must meet current uplift resistance requirements in ASCE 7. If it cannot, then it must be replaced not recovered. Using this approach could have prevented an issue that now, according to Ron (after further investigation), will require replacement of the deteriorated LWIC fill. Whether this is replaced with tapered insulation or new LWIC, it will clearly add increased complexity and cost in order to achieve a proper code-compliant roof replacement.

2020 Florida Building Code, Existing Building, 7th Edition

CHAPTER 7 ALTERATIONS—LEVEL 1

SECTION 706 EXISTING ROOFING

706.3 Recovering versus replacement. New roof coverings shall not be installed without first removing all existing layers of roof coverings down to the roof deck where any of the following conditions occur:

1. Where the existing roof or roof covering is water soaked or has deteriorated to the point that the existing roof or roof covering is not adequate as a base for additional roofing.

2. Where the existing roof covering is wood shake, slate, clay, cement or asbestos-cement tile.

3. Where the existing roof has two or more applications of any type of roof covering.

4. When blisters exist in any roofing, unless blisters are cut or scraped open and remaining materials secured down before applying additional roofing.

5. Where the existing roof is to be used for attachment for a new roof system and compliance with the securement provisions of Section 1504.1 of the Florida Building Code, Building cannot be met.

Exceptions:

1. Building and structures located within the High-Velocity Hurricane Zone shall comply with the provisions of Sections 1512 through 1525 of the Florida Building Code, Building

2. Complete and separate roofing systems, such as standing-seam metal roof systems, that are designed to transmit the roof loads directly to the building’s structural system and that do not rely on existing roofs and roof coverings for support, shall not require the removal of existing roof coverings.

3. Reserved.

4. The application of a new protective coating over an existing spray polyurethane foam roofing system shall be permitted without tear-off of existing roof coverings.

5. Roof Coating. Application of elastomeric and or maintenance coating systems over existing asphalt shingles shall be in accordance with the shingle manufacturer’s approved installation instructions.

Mike Silvers, CPRC is owner of Silvers Systems Inc., and is consulting with FRSA as Director of Technical Services. Mike is an FRSA Past President, Life Member and Campanella Award recipient and brings over 40 years of industry knowledge and experience to FRSA’s team.