8 minute read

CHRISTMAS ON CALL

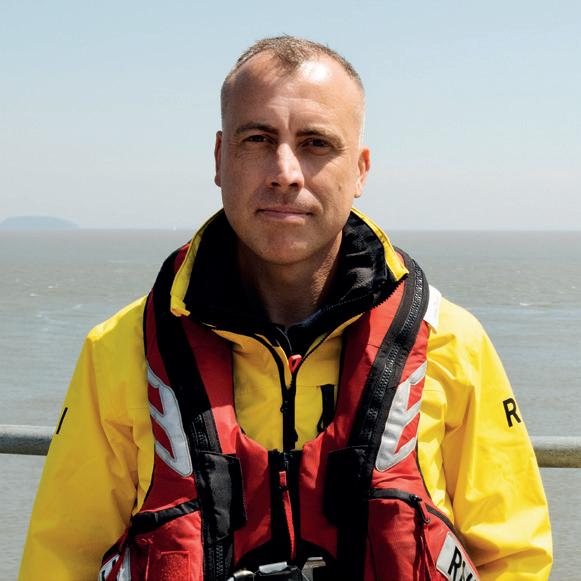

With a man overboard in freezing seas, the lifeboat crew knew it was critical to reach him fast

Andy Gavan, Coxswain of Barry Dock lifeboat, was getting ready for a Christmas do on 26 December 2023 when his RNLI pager shrieked into life. ‘I was already dressed up for the party, so I ran to the station in my waistcoat and bow tie,’ he remembers. ‘We’re usually a little quieter at that time of year, so when the pager goes off it can be a surprise. And winter shouts, naturally, tend to be more serious.’

Floating somewhere outside Barry Harbour, Tom Skinner was in serious trouble. He was following a strict training regime for a major rowing event, when he was thrown from his boat by a powerful current near Lavernock Point. He managed to radio for help but, after drifting in dangerously cold water for around 45 minutes, Tom’s body was seizing up and he was starting to lose hope.

Both Barry Dock and Penarth lifeboat crews were alerted, along with the coastguard helicopter based at St Athan. Already in flight, the helicopter crew hadn’t found Tom – he was just a tiny speck in the sea.

Kitting up at Barry Dock lifeboat, Andy was alarmed to hear how long the casualty had been in the cold water. ‘It was critical we found him quickly,’ he says. ‘I knew it wouldn’t be long before he was unconscious.’

The Barry Dock volunteers had an expanding search pattern prepared as they launched their all-weather Trent class lifeboat Inner Wheel.

'In winter the water is extremely cold. I knew it wouldn’t be long before he was unconscious’

The crew knew their casualty would be drifting west on the choppy tidal flow of the Bristol Channel and they calculated Tom’s rate of drift. ‘Knowing how fast our tide runs, I knew he’d probably travelled 2 or 3 miles,’ says Andy. Combining this with all their local knowledge, they had a good idea of where to start looking. They headed for an area near Rannie Buoy.

With three crew members on deck acting as lookouts; one preparing oxygen, first aid and blankets; and two readying the A-frame gantry to lift their casualty from the water, they hoped they would find Tom sooner rather than later. Then, about a mile south of Sully Island, Crew Member Josh Brown spotted ‘something like a football’ off the starboard side. As the lifeboat drew closer, they realised it was the back of Tom’s head – and he was still alive.

‘I carefully pulled the lifeboat alongside him,' says Andy. 'It was surreal – he was still gazing out to sea.’ The cold had robbed Tom of most of his faculties and he hadn’t noticed the big orange lifeboat behind him. ‘They were almost on top of me before I realised they were there,’ says Tom. ‘I could hear them shouting. That’s when I thought: it’s alright, I’m going to be OK.’

‘I could sense these incredibly calm, professional people operating all around me'

Already prepped to recover him starboard side with the A-frame and strops, the lifeboat crew swiftly hauled Tom out. ‘I was very pleased to be out of the water,’ he says. ‘But I could sense I wasn’t quite in the clear. I couldn’t move my arms and was really struggling to breathe.’ The crew immediately began casualty care. Quickly recognising the signs of hypothermia and water inhalation, they wrapped him in blankets and delivered oxygen. By now, Penarth lifeboat crew had arrived on scene in their Atlantic 85 lifeboat Maureen Lilian. The inshore crew offered to transfer their trained paramedic Nic Anderson to help onboard the all-weather craft. Simultaneously, Barry Dock crew were trying to request an extraction of their casualty by helicopter. A combination of poor reception and heavy radio traffic meant neither call landed successfully. Barry Dock Lifeboat Mechanic Ben Phillips, doubling up as radio operator on the Trent, explains: ‘At this point we struggled to get a clear VHF transmission, our comms were squelchy and unintelligible. And with so many different vessels trying to speak, including a clutch of nearby fishing boats, it was difficult to get in.’

Barry Dock lifeboat headed straight for harbour and the Penarth crew followed them in. As the all-weather lifeboat reached its pontoon, the coastguard helicopter landed nearby and its paramedic came aboard. As the helicopter no longer had enough fuel to lift Tom to hospital, the gathered lifesavers agreed to look after Tom in the warmth of the lifeboat station while they waited for an ambulance.

‘As the radio chatter started to quiet down, it became clear that Penarth lifeboat had pulled up with a paramedic onboard,’ says Andy. ‘We called for her to join us in the lifeboat station.’ With Nic taking over casualty care, the helicopter could now leave and refuel for its next mission.

The RNLI crew carried their casualty to the lifeboat station’s wet room and started showering him in tepid water. He wasn’t talking, but was able to nod to questions and open his eyes when asked.

Nic took regular observations and kept Tom on oxygen while others brought drinks, towels and blankets. They slowly warmed him up and administered tubes of glucose gel to boost his energy. ‘Ellie, another paramedic from the Penarth crew came by car to support Nic,’ says Andy. Barry Dock and Penarth RNLI volunteers pulled together for more than an hour to ensure Tom’s safe recovery. By the time the ambulance arrived, he was alert and chatting.

‘It was heart-warming to hear that Tom made a complete recovery,’ says Andy. ‘He came back to the lifeboat station to thank us all personally too. Rescues like this really stay with you – they remind us why we put so much into our training, and why it’s so important to work together as a team with our fellow lifeboat crews and other emergency services.

‘None of it can happen without kind donations from the public. They fund the kit, training and equipment we need to continue responding to emergencies like this. And there’s no doubt our new lifeboat station and facilities really helped on this one. The warm shower, underfloor heating and extra room to carry out casualty care all contributed to saving Tom’s life.’

‘He was pale and cold to touch, beyond shivering'

‘Tom was pretty unresponsive to start with and his breathing was shallow and rapid. The Barry Dock volunteers were amazing – some were in the shower with him, slowly bringing up the temperature and coaching his breathing. Others gently stepped up his drinks from cups of tepid water to hot tea. That allowed me to focus on taking regular observations like his pulse, temperature, respiratory rate and sats (blood oxygen). Tom’s sats remained low so I kept him on the oxygen for quite some time. When I was happy his temperature was at normal levels, we got him out of the shower, dried him off and put him in warm clothes.’

'I started to think this might be it …'

‘When you hit water at 8°C, it takes your breath away. I tried swimming after my boat but couldn’t make any headway –that’s when I realised I was in trouble. It becomes difficult to move or think properly in water that cold. I knew my only chance was to conserve energy. It was pretty lonely out there – I started to think this might be it. I’ve got a 7- and 5-year-old, and I was thinking about them too. Thankfully, the lifeboat crew came alongside and pulled me out of the water. I wasn’t sure what was happening but could sense these incredibly calm, professional people operating like clockwork all around me. I thank them all for dropping everything to help me.’

The difference you make

Coxswain Andy Gavan spells out what the new station at Barry Dock means to the crew: ‘Our old boathouse was a lot smaller and we only had an outside shower that ran cold. In this rescue, when we got Tom back to our new station with its underfloor heating, it was ideal – we could gently thaw him out under the warm shower. We also set up a separate resus room, just in case things took a turn for the worse. We didn’t have that option before.

Words: Jon Jones. Photos: Stephen Duncombe, Luc Lacey, RNLI/(Barry Dock, Nigel Millard), UAV Aspects, Imogen Williams