3 minute read

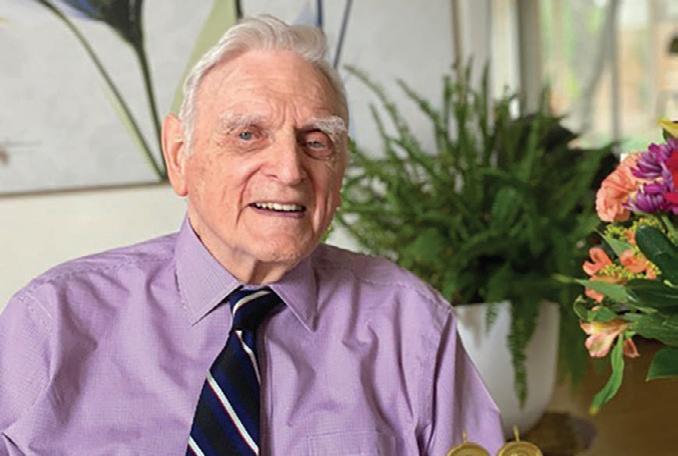

John Bannister Goodenough, 1922-2023: 'A life well lived'

We are sad to report that John Goodenough, father of the lithium ion cell, and one of the three figures that created today’s huge lithium battery industry, died on June 25 a month short of his 101st birthday.

John, who was interviewed several times for Batteries International, was awarded the joint Nobel Prize for Chemistry in October 2019 with the two other pioneers of the lithium battery, Stanley Whittingham and Akira Yoshino.

Advertisement

In our subsequent interviews with Whittingham and Yoshino each acknowledged the huge debt the world owes to Goodenough who discovered the cathode material of choice and so made the lithium ion battery truly portable and rechargeable.

“John was an unassuming, modest and gentle man whose work has touched everyone’s life,” said Bob Galyen, the former CTO of CATL and a friend. “It was a life well lived and John had an intellect of astonishing proportions and his contributions to science extend well beyond the lithium cell.”

Oddly enough for someone whose research has ended up in the household or pocket of most of the planet, he was regarded as a backward child. It was only much later that it was found that he was dyslexic and he later described how he dealt with this problem by studying abstract mathematical thought and Greek and Latin.

Aged 18 he left school as top of his class and received a scholarship to Yale. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, he volunteered for service, but was not called up until January 1943. This gave him time to complete his undergraduate degree in mathematics. He had entered Yale as a freshman with a background in Latin and Greek and little idea of what he would do after the war was over.

He graduated while working as a meteorologist in the US Air Force. A crisis of faith around this time led him to dedicate himself to a life of service starting with studying physics at the University of Chicago or Northwestern University.

“When I arrived at Chicago the registration officer, professor Simpson, said to me, “I don’t understand you veterans. Don’t you know that anyone who has ever done anything interesting in phys- ics had already done it by the time he was your age; and you? You want to begin?”

Undeterred, he earned a master’s degree in 1951 and a doctorate the following year.

Ground breaking

For the next six decades his astonishing academic career and research led him from his early work at MIT on computer memory to the University of Oxford in his 50s where most of his ground-breaking work on lithium cells was pioneered. The last three decades of his life were at the University of Texas, where he held the Virginia H Cockrell centennial chair in engineering.

He was still working until his late 90s and in the last years of his life was pioneering a solid state battery.

As recently as 2017 he announced patents for new battery cells using a solid glass electrolyte instead of a liquid one, using an alkali metal anode. The glass electrolytes allow for the substitution of low-cost sodium for lithium. This had the possibility of being a second worldchanger to the energy storage industry.

Caring little for money, John signed away most of his rights. He shared patents with colleagues and donated stipends that came with his awards to research and scholarships.

He was married to Irene Wiseman for 65 years. She died in 2016. In the latter part of her life he would work at the university in the morning and visit her care home in the afternoons, she suffered from dementia.

In addition to being a Nobel laureate John was feted internationally being a member of the US National Academy of Engineering a member of the National Academy of Sciences, French Academy of Sciences, the Spanish Royal Academy of Sciences, and the National Academy of Sciences.

He wrote more than 800 articles for scientific journals, 85 chapters and eight books. He was a co-recipient of the 2009 Enrico Fermi Award and elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society and was presented with the National Medal of Science by US president Barack Obama.

Among his many publications is a very personal one: “Witness to Grace”, in which he describes how his intellectual journey had also included “a religious quest for meaning in what or whom I would choose to serve with my life.” He was born into an agnostic family but during the war years he developed a faith and was a devout Christian to the end of his life.

Career development

To return to his spectacular career: the crucial point in Goodenough’s researches and associated lithium battery’s development was when he was offered a position of professor and head of the Inorganic Chemistry Laboratory at Oxford University.

Up till then. Goodenough had been