5 minute read

DALE KYNOCH

Student Manifestos

DALE KYNOCH

As always, I look forward to fresh faces each September — particularly as the transition to third grade is always a special one at St. Andrew’s. In the past, the second graders transitioned from one campus that housed the youngest students at St. Andrew’s, and moved to the “big campus” in the fall. Now that we have expanded to become a one-campus school, third grade marks a transition from the first floor of our lovely new Lower School building, shared by our Preschool through second grade students, to the second floor which is the domain of the third through fifth graders. Looking at these apprehensive, curious, and innocent faces, I always wonder what their hopes and dreams for the new school year are, and what personality traits they will bring to the classroom that will make it a unique group of children.

St. Andrew’s is a school that focuses on Mind, Brain, and Education Science, so it is expected that faculty use current research to inform their teaching practice. It has a side benefit of making St. Andrew’s a really fun place to work. In third grade, we focus on growth mindset and student accountability as starting places as the students learn to define who they are as students, and what their personal responsibility is in their own learning.

Meanwhile, when the students enter the classroom, their parents do, too. I know, from years of experience, that the students have parents that practice parenting in

equally unique ways, and this is a wonderful thing. I also know that each parent has their own hopes and dreams for their child’s learning. Ahh, the joyous dilemma of third grade — that transition from one floor to another is also a transition in independence and metacognition, and it is work for both the students and the parents. How to get these students to take control over the part of their learning that they are developmentally ready for, and to start to define their life as a student in a way that is meaningful to them? How to help parents support their child in this time where increasing selfknowledge and independence as a learner is developmentally appropriate?

On alternate Wednesday mornings we delve a bit deeper into growth mindset, based on work by Carol Dweck, 1 and including materials created by Christina Winter. 2 In this program, students learn all about their brains and why they are unique as children and as learners. Using videos and read-alouds, we do multiple lessons on mindset that challenge the students to think deeper about their own learning.

Students think about the distinction between growth and fixed mindset by learning about different parts of the brain and what they do, that their brains change over time, how to grow their brains, and why students need to be vulnerable in order to have a growth mindset. Students learn how “hard things” help them grow and develop perseverance; how frequent check-ins with teachers are useful and effective for reflecting on their work; and that knowing that concepts

like “grit” and “stamina” and “passion” are necessary to help them define who they are and what they stand for; and how the best way to grow a brain is through mistakes, and the power of “yet.” The students love this work and I hear them using the positive terms when talking about their work and the work of others... while in the classroom.

Outside of class, this positive self-talk often disappears. In the hallway I hear students say to each other, “Ugggg, it’s math time. I am really bad at math.” Or, “I wish I could do like does. I stink at it.” This agrees with Dweck’s work, which says that growth mindset tends to be context dependent — I might have a growth mindset in this subject or at this time, but a fixed mindset in others. But Dweck also suggests that we can shift our mindset. So I wondered, what could I do to help the students consistently apply the growth mindset lessons to their everyday experience, not just on demand in the classroom? That’s where student manifestos came to mind.

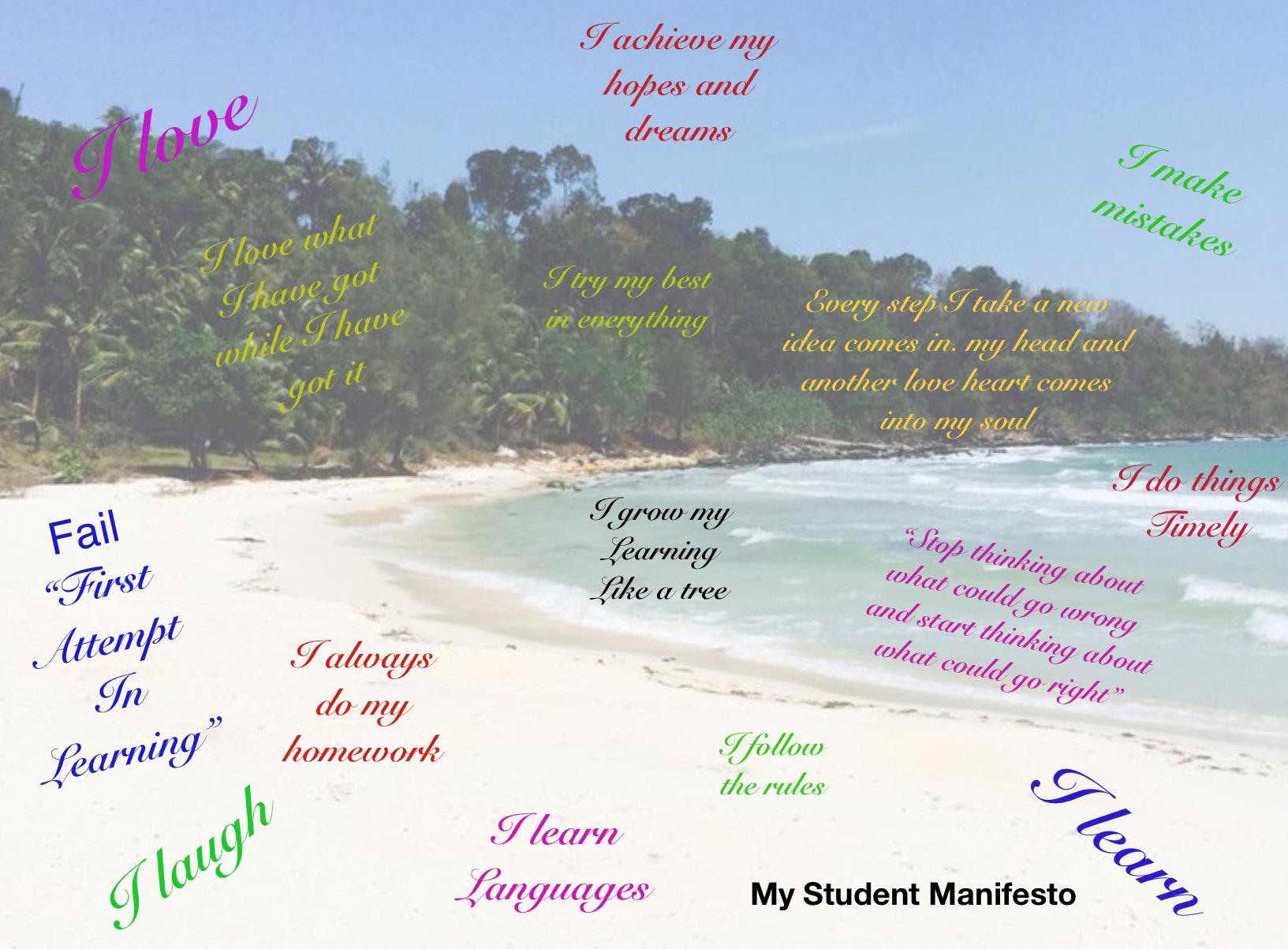

After lessons on growth mindset, students create a visual representation of their thinking around growth mindset. After showing multiple examples, the students set to work on their iPads reflecting on their growth as a student. They use a soothing background, usually a picture, and then create “I am…” statements to place on their chosen background. They also search for meaningful quotes from some of their everyday heroes. Some write poems, often acrostic, to further define themselves. It takes weeks of reflection, going back and adding to or tweaking their manifesto, before they create a final product for display.

As they do this work, students start to outline their unique strengths and accomplishments. They get in the habit of finding insights about themselves as learners as they go about their regular school day, and use this to update their manifesto. The results are as varied as they themselves are.

Once done, we post the manifestos in the hallway, in the classroom, and on the front of their binders. They share their work with their parents and each other. They are proud, and should be, of their reflections. This project that started off about growth mindset has expanded into one that is also about metacognition, knowing about myself as a learner — and research suggests that metacognition is a very powerful research-informed strategy.

What’s next? Digging deeper, of course! This year we will use some work of James Clear to further explore the meaning of habits and how to make the good ones stick. 3 Can we add this to our investigation of, “who am I as a learner? What strategies work for me?” Who knows what the students will create.

As one of my colleagues once stated, “Teachers are lucky, we are the only profession that gets to reflect and recreate each summer and welcome a new class each fall.” Always a new class of fresh faces and new opportunities.