5 minute read

WHEN BREATH BECOMES AIR FINN GAVIN

WHEN BREATH BECOMES AIR

A REVIEW OF A BOOK BY PAUL KALANITHI

Advertisement

BY FINN GAVIN (09-20)

‘T he good news is that I’ve already outlived two Brontës, Keats and Stephen Crane,’ wrote the 37 year old Paul Kalanithi shortly after learning of his terminal cancer diagnosis in an email to his closest friend. ‘The bad news is that I haven’t written anything.’ As one final act of striving, Dr Kalanithi set about writing his memoirs, drawing on his experiences as a student, doctor and patient in a noble, insightful bid to answer the question he had pursued for his whole life: what makes life meaningful? Heartbreakingly poignant, the moving result of a tragically short lifetime is simply stunning.

Dr Kalanithi’s background in English Literature is central to the vital spirit of the book, a reflection of the importance of the written word in the author’s identity. From an early age, his life was infused with literature and medicine — his father a cardiologist, his mother a ferocious advocate of literature in the young Paul’s education.

Originally turned off by medicine, blaming the profession for his father’s absence in the family home, Kalanithi said, ‘Books became my closest confidants, finely ground lenses providing new views of the world’. At Stanford (his alma mater), as well as attaining a BA and MA in English Literature, the future neurosurgeon took a keen interest in biological science (he also had a BA in Human Biology). I find the refusal by Kalanithi to accept the boundaries between academic disciplines compelling, and inspiring. He recognised that the complexity of the meaning human life and the suffering of his patients could never be understood if he limited himself purely to the sciences or the arts (as so many felt they must) and so it was he ‘studied literature and philosophy to understand what makes life meaningful, studied neuroscience and worked in an fMRI lab to understand how the brain could give rise to an organism capable of finding meaning in the world’.

Dr Kalanithi spends a good portion of the book meditating on his time as a medical student and neurosurgical resident. For me, about to embark on my own journey through medical school, these passages were enlightening, his words serving a warning of what to expect, and what I could become. For Kalanithi, his greatest fear was losing sight of his search for meaning which drove him to his scrubs in the first place. He writes, ‘I had started in this career, in part, to pursue death: to grasp it, uncloak it, and see it eye-to-eye, unblinking. Neurosurgery attracted me as much more its intertwining of brain and consciousness as for its intertwining of life and death’. After feeling ill at ease in academia following his MA — his focus on the Spiritual-Physiological man in Whitman’s poetry deemed too biological for mainstream English literature — clinical practice was attractive to him for its raw view of human nature which is only revealed in the crises which define our live — sickness. ‘I feared I was becoming Tolstoy’s stereotype of a doctor,’ he writes, ‘preoccupied with empty formalism, focused on the rote treatment of disease — and utterly missing the larger human significance.’ Becoming inured to his patient’s pain was intolerable for Kalanithi, his introspection on his own failings in pursuit of his goal of a comprehensive understanding of meaning in life is both a welcome breath of humility but also a reminder to us all that it is okay to take a misstep when striving towards the greatest good if we can recognise it and be willing to adapt. Ultimately what makes this such a special book is its frank depiction of suffering. Kalanithi opens the book with his diagnosis, putting himself in an immediately vulnerable position. He feels, ‘Tethered to an IV pole’ and laments that he was ‘So authoritative in a surgeon’s coat but so meek in a patient’s gown’. There is a sense of loss: despite having spent his career surrounded by suffering and guiding patients to a better understanding of what it means for them he felt totally unprepared for what he had to go through. Kalanithi’s story gives an insight into the patient from the perspective of the doctor, it is the reverse side of the coin, the backstage drama. It’s the immeasurable tragedy of the individual in the face of mortality. It’s life, death, nihilism and ambition. Kalanithi’s words are vulnerable, touching, wise and hauntingly beautiful. His message is wholly unforgettable.

I have to admit, this review is somewhat biased: When Breath Becomes Air is my favourite book. But I think that’s okay. Kalanithi’s writing, his experiences, his observations speak to me in a way no other book has. His poetic command of English captivates me every time I encounter it. As he begins to deconstruct the doctor-patient relationship I can’t help but feel inspired to pursue medicine, to pursue meaning. When one ‘of the many moments in life where you must give an account of yourself, provide a ledger of what you have been, and done, and meant to the world’ comes along, Kalanithi urges us to have something to offer. For Paul lying on his deathbed looking at his infant child, Cady, and his wife, Lucy, it was this book. The climax of his contributions to society, to his family, came in his final moments — and it was painful! It’s a book about growing, and decaying, and dying. It’s a book about the second law of thermodynamics. It’s a book about a man who will never reach his full potential as he perceived it. ‘Everyone succumbs to finitude,’ he writes towards the end. This book is a tragedy. Every heartbreaking word of it makes me want to be the best version of myself I can possibly strive to become. Practicing medicine is simultaneously the art and the science of caring for the infirm. Paul Kalanithi mastered both — that is something to which we can all aspire.

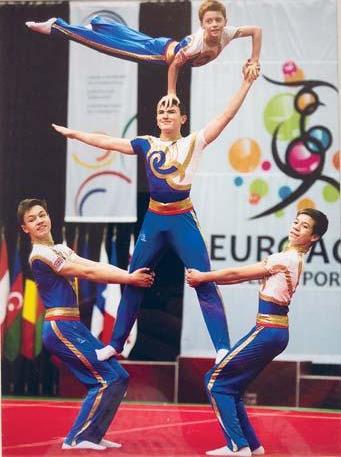

Junior Acrobatics European Championships 2013. Finn on top; Michael Gill (09-16) right