5 minute read

Drawn Into History

from ONA 96

By Roisin Inglesby (03-05), curator of architectural drawings, Historic Royal Palaces

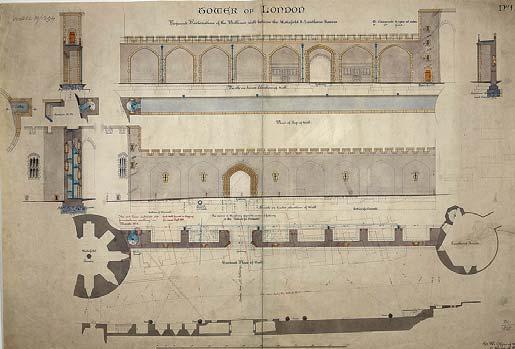

Above: Roisin Inglesby presenting architectural drawings to a group of visitors. Copyright Wienerberger Ltd Below: Architectural drawing showing the re-medievalisation of the Tower of London in the 1880s. Copyright Historic Royal Palaces I t would be hard to find a more atmospheric place to work than the Tower of London. Once all the visitors have gone for the evening I leave my office and walk through the shadow of the White Tower, built by William the Conqueror in the 1070s. I walk past the execution spot on Tower Green, believed to be where Anne Boleyn lost her head, and through the vaulted arch of the Bloody Tower, prison to Sir Walter Raleigh and, legend has it, the unfortunate Princes in the Tower. In the winter months I make this journey in the dark and it is by turns beautiful, awe-inspiring, and slightly creepy.

Advertisement

This is not to say that the Tower is deserted after dark. The site has continually served as a home to many for over 900 years and this tradition is maintained by the present community of Yeoman Warders (better known as Beefeaters), who live within the walls. There are also army barracks on site, all that remains of the Tower’s important military function — it was until the 19th Century the home of the Board of Ordnance, which supplied munitions and equipment to the Army and Navy. In its long history the Tower has also served as a palace for generations of kings and queens, the Public Records Office, a safe house for the Crown Jewels, and the Royal Mint.

In comparison with its thousand-year history, I have only been at the Tower for a very short time indeed. In May 2015, I took up the position of curator of architectural drawings for Historic Royal Palaces, the organisation which cares for the Tower, Hampton Court, Kensington Palace, Kew Palace, and the Banqueting House in

Whitehall. I look after almost 30,000 architectural drawings which cover all the palaces, but are all kept together in a vault in the Tower’s Waterloo Block, in a basement underneath the Crown Jewels. The high security is only in part because of the intrinsic value of the drawings. More important is the fact that the space is climate-controlled, as fluctuations in temperature and humidity — common in old buildings — can be very damaging to paper objects.

I’ve been fascinated by history for as long as I can remember, and after leaving RGS in 2005 I studied Modern History at Queen’s College, Oxford. In my final year I became interested in the idea of visual sources and the stories they can tell. After failing (twice) to get a place on a History of Art course at the Courtauld, I worked at Christie’s for a year, a very valuable experience of close contact with the thousands of objects that pass through its doors each month. It was at this point that I discovered the concept of ‘material culture’, a relatively new, interdisciplinary academic approach that seeks to understand the past though the investigation of things. The idea of material culture studies is that the manufacture of your hat or the design of your kitchen probably explains more about your world than the latest government policy or multi-million pound piece of art: it aims towards a democratic understanding of what constitutes culture and focuses on the importance of objects within our everyday lives.

In 2009 I was fortunate to receive a scholarship to study for an MA in the History of Design, Decorative Arts and Material Culture at the Bard Graduate Center in New York (the fact that two out of three interviewers happened to be from Newcastle can’t have done any harm!) and I spent a brilliant two years in Manhattan, before taking a job as assistant curator of designs at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. The V&A’s collection is one of the best in the world, and I was responsible for about 100,000 design drawings, ranging from 15th Century stained glass designs to designs for 21st Century fashion. During this time I started to focus more on architecture, and in 2015 curated a small exhibition about Philip Webb, best friend of William Morris and the founder of Arts and Crafts architecture.

One of the nicest things about working in museums is the day-to-day variety. Some days I spend in the stores, seeking out particular things on behalf of colleagues and researchers. I facilitate public access, which means showing drawings to visitors, but also working on improving the catalogue records and arranging a programme of photography with the aim of one day having everything publically available online. I give talks and tours of the space, and in spring 2016 I am undertaking a threemonth research secondment investigating a group of drawings showing the restoration and re-medievalisation of the Tower in the 19th Century. I’m expected to keep up-to-date with the legal responsibilities of having a public collection, ensuring we have adequate policies for acquisitions and disposals, and the ensuing paperwork. I’m also responsible for the drawings’ physical well-being,

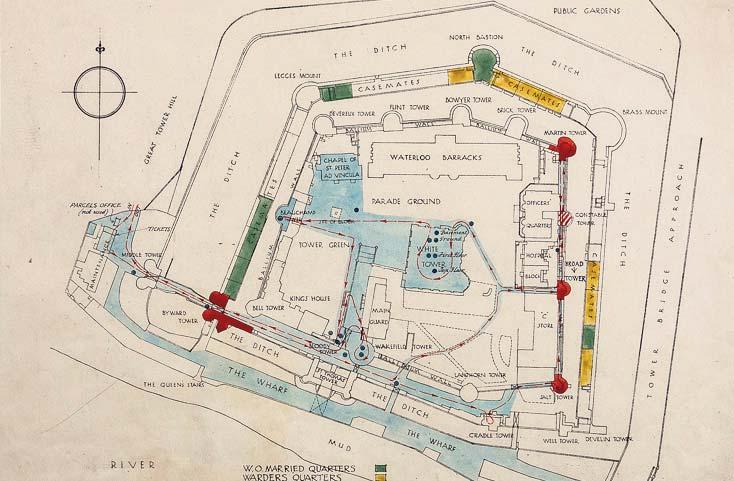

Top: Plan and elevation of Subway entrance, Tower Hill, circa1910. Copyright Historic Royal Palaces Middle: Part of the 14th Century mural in the Byward Tower. Copyright Historic Royal Palaces Bottom: Architectural drawing showing parts of the Tower open to the public and parts inhabited by Yeoman Warders, 1920. Copyright Historic Royal Palaces

so I work closely with the conservation department to ensure that everything will be kept safe for several hundred years to come! A really lovely aspect of the job is having privileged access to parts of the palaces not normally seen by the public, whether this is the room at Hampton Court once used as a library by Henry VIII, the servants’ quarters in the attic at Kensington Palace, or the spectacular wall painting in the Byward Tower at the Tower of London.