4 minute read

Mark Akenside

from ONA 97

Mark Akenside Poet and Physician: A Lover of Contradiction

By Alan Castree (53-61)

Advertisement

Many Old Novos will recall the refrain in the school song, “… Collingwood, Armstrong, Eldon and Bourne, Akenside, Stowell and Brand…”, but perhaps not too many will know much about this exceptional character, Mark Akenside. He has an unfortunate reputation today, having engendered in Geordie folklore the “Akenside Syndrome”, symbolizing someone who moves away from the Tyne, becomes famous and disclaims his native origins. I judge this unfair but readers can decide.

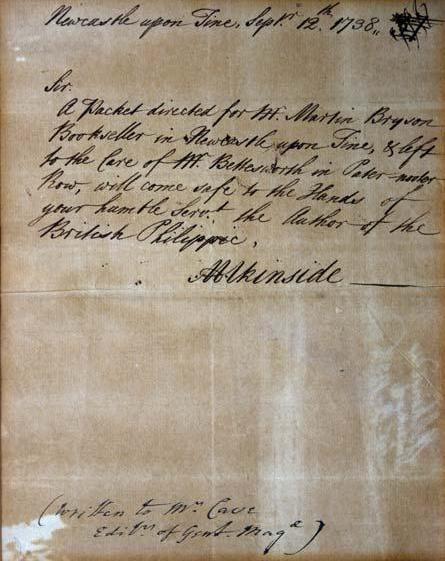

Above: Mark Akenside © Royal College of Physicians Above right: Mark Akenside’s letter to Mr Edward Cave, editor of the London periodical, The Gentleman’s Magazine, sourced from the school library, dated 1738 M ark was born on 9 November 1721, the son of a Newcastle butcher. His family were Presbyterian Dissenters. From an obscure background, Mark rose to become a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, Fellow of the Royal Society and physician to Queen Charlotte, wife of George III. Further, he achieved wide acclaim as a leading poet of his age and as a brilliant classical scholar.

He attended RGS in the 1730s (actual dates unknown) and also received education from William Wilson at the Non-Conformist Meeting House, Hanover Square, Newcastle. Support from his church enabled him to enter Edinburgh University to read Theology in 1738. A bright and industrious scholar, he chose to switch to Medicine, in which he was to excel. He built a reputation as a fierce and able debater, displaying early signs of a disputatious manner that proved to be an irritant to many during his life.

He wrote what proved to be his most successful poem in 1743, The Pleasures of the Imagination, a work of 2,000 lines. Anne Barbauld, editing his poems in 1794, considered this remarkable for such a young man, with a wry comment on its erudition: ‘Akenside will not call people from the fields and the highways to partake of his feats; he will wish none to read that are not capable of understanding him’.

Mark negotiated a healthy fee for his work, thanks to positive backing from other poets, including Alexander Pope. Success was immediate and through this achievement his name was prominent in literary circles throughout the rest of his life.

In 1744, Mark moved to Leiden University, to extend his medical qualifications, after which he tried, unsuccessfully, to build a medical practice in London, but to him, progress was too slow. Those who knew him were not surprised: the coffee house chatter was that his practice was slow to blossom because his abruptness of manner failed to accord to any prospective patients the respect that they felt they deserved. In Tom’s Coffeehouse, Devereux Court, near Temple Bar, his excitable temperament led him into lively arguments with all and sundry, night after night.

He seems to have survived these early days through his literary earnings and the unfailing generosity of Jeremiah Dyson, a barrister and later clerk to the House of Commons, whom Mark had befriended in Edinburgh and who, after Mark’s premature death, edited and published a posthumous collection of his poems in 1772.

In 1749 he devoted more time to medicine and less to his verse. He became a licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians in 1751, received the degree of MD by mandamus from Cambridge in 1753 and became a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians in 1754. He wrote authoritatively on Medicine and earned praise for the elegance of his Latin.

In 1759 he became principal physician at St. Thomas’ Hospital and in 1761 gained his royal appointment. As he had been quite open about his republican views before this, there was bitter comment among his immediate circle about the latter appointment.

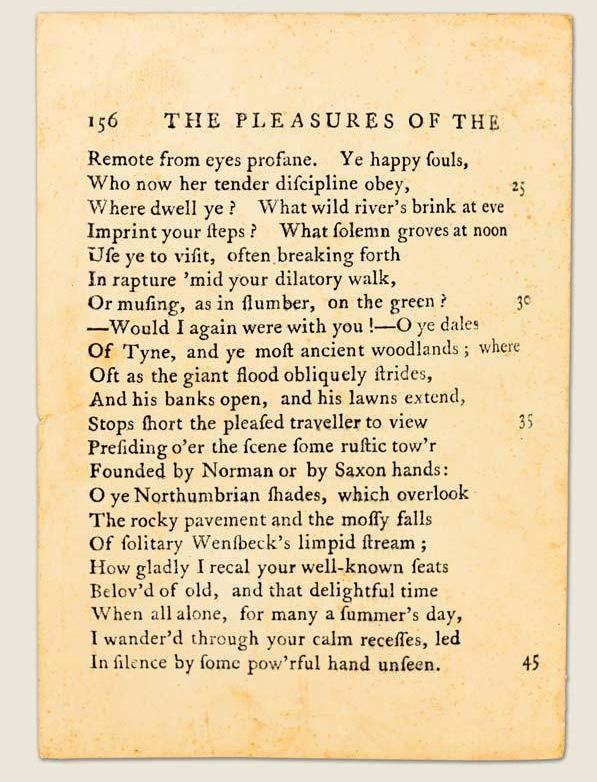

Samuel Johnson saw Akenside as a lover of contradiction and no friend to anything established, and Mark often engaged in satirical attacks on well-known figures: satire was a feature of the time. Tobias Smollett took exception to his hostility towards the Scots and cast him as a didactic doctor, pompous and humourless, in The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle. Mark did not respond. He endured jibes about his lowly origins: any provincial keen to make his way in London had to survive the snobbery and contempt in society towards outsiders. He was not, however, the spiteful critic of other poets that many versifiers tended to be: he was constructive and warm in his praise. His writing ranged from classical allusion to rural nostalgia and he was affectionate towards his native county as in The Pleasures of the Imagination:

‘…Would I again with you! O ye dales Of Tyne, and ye most ancient woodlands…’

‘…O ye Northumbrian shades, which overlook The rocky pavement and the mossy falls Of solitary Wansbeck’s limpid stream…’

Surely this is from the hand of a lover of his north eastern heritage?

An incurable suppuration of his throat led to his early death in 1770 and he was buried at St. James’ Church, Piccadilly.

Mark Akenside was an outstanding poet, scholar and physician and deserves to be remembered as a remarkable Northumbrian who, while not proclaiming his humble origins from the rooftops, did, nevertheless, pay true homage to where his roots lay.

A more detailed version of this article can be found on the ONA website at http://bit.ly/223OX7M

Akenside paying homage to his north eastern roots in The Pleasures of the Imagination, published 1744. It is thought that he got the idea for this poem after a visit to Morpeth in 1738