6 minute read

From Gateshead to Gallipoli

from ONA 65

From Gateshead to Gallipoli A GP goes to sea

By Dr Greg Brown(91-96)

Advertisement

HMNZS Te Kaha with her Seasprite helicopter and a Royal New Zealand Air Force P3 Orion surveillance aircraft, on operations in the western Indian Ocean Life on the high seas, serving the same Queen but a different country, was not a likely trajectory for my career when I left the RGS in 1996. This year, however, I found myself as the embarked medical officer with the New Zealand frigate HMNZS Te Kaha, engaged in counter-narcotics work in the western Indian Ocean.

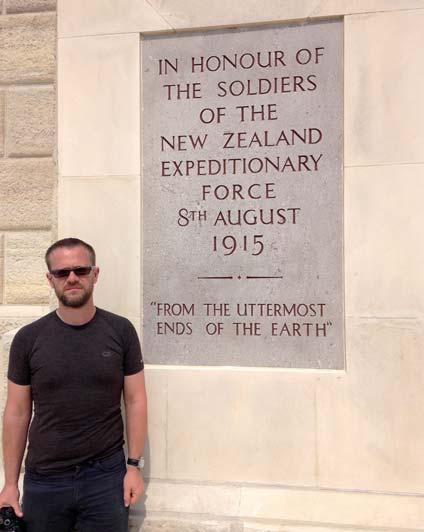

Greg at the Chunuk Bair Memorial Anzac Cove Cemetery

After leaving school I initially read History at Sheffield, but by the completion of that degree my interests and aspirations had taken a different turn. In 2000 I commenced a medical degree, graduating with Honours in 2005. Having trained as a GP, I moved to New Zealand in 2011 with my young family. This was supposed to be a temporary move designed to facilitate General Practice experience in a different context, before returning to the UK and taking up a GP partnership role. Before the year was up, my wife Julie and I had fallen completely in love with New Zealand and decided to stay, settling near Wellington.

Being on the lookout for a permanent position, I stumbled across an advert for a civilian medical officer post on the local Army base. It looked like an interesting niche role, with a heavy bias on sports medicine and preventative care, so I applied and subsequently got the job. I have now been in post for two years and it has exceeded my expectations. Much of the time I am dealing with generally well-motivated patients who want to be well, and this is a huge pleasure. However, military personnel suffer the same medical issues as anyone else, except that diagnoses also potentially convey implications for deployability (and often ongoing employability), and this frequently becomes highly complex.

Having been in post for some months, I was finally persuaded to investigate the possibility of putting on a uniform. I elected to do the required training to be commissioned as a reservist in the Royal New Zealand Navy, completing this in July 2014 at the age of 36. I then continued in my civilian role, while undertaking courses in sea survival and damage control (fighting fires and stopping leaks) to become qualified to go to sea.

In April this year, I flew to Crete to join HMNZS Te Kaha (which had left New Zealand two months previously) on my first deployment. Before commencing our counter-narcotics operation, we had the immense privilege of taking part in the centenary commemorations of the Anzac landings at Gallipoli, performing a sail past Anzac Cove in convoy with British, Australian, French, and Turkish warships. The dawn was breaking over Chunuk Bair as my shipmates and I slowly sailed by, at the same time our forebears had gone ashore 100 years previously. Even as an adoptive New Zealander, this was a uniquely special occasion, an unrepeatable moment, more profound than any of us could fully articulate. A week later we were able to get ashore to tour the battlefields for ourselves, following a fascinating port visit to Istanbul.

Ceremonial duties over, we passed through Suez into the Red Sea to start the operational phase. Working under Combined Maritime Forces, a multinational naval partnership aiming to disrupt both piracy and the trafficking of narcotics off the Horn of Africa, Te Kaha patrolled a sector of the western Indian Ocean for the next few weeks. The so-called “smack track” runs illegal narcotics (principally heroin and hashish) out of Afghanistan, through Pakistan, and onto tiny boats (called dhows) which attempt to drop

their cargoes at various points down the coast of east Africa. The dhows do not show up well on radar, and the ocean is a rather large place, so there is heavy reliance on intelligence gathering and visual searches using either our own helicopter or other surveillance aircraft (including a Royal New Zealand Air Force P3 Orion later in our trip).

For the first month on task, our boarding teams did a number of searches of suspicious vessels, but unfortunately weren't successful in locating any narcotics. All that changed after our mid-tour port visit to the Seychelles, when we discovered nearly 140kg of heroin hidden behind a false bulkhead on one dhow, followed by a second haul of 110kg. The estimated street value totalled over US$100million. Having spent a proportion of my career dealing with the effects of heroin addiction, it was fantastic to see kilogram after kilogram being destroyed. Arguably a small contribution to the war on drugs overall, but thoroughly worthwhile nevertheless.

My role as the medical officer was to look after the crew to the best of my ability, liaising with the command team to try and ensure that medical issues minimially impacted on the operation. Much of the time we were several days sail from getting the helicopter within range of land, so avoiding unnecessary evacuations was critical to ensure the ship remained on task. It has been said that the core skill of a GP is managing uncertainty, and this was certainly employed when it wasn’t clear exactly what was going on with a patient and diagnostic investigations were unavailable. I also do some minor surgery as a GP, and these skills were pushed to the edge of my comfort zone on a couple of occasions. Overall, though, the trip was very successful medically, and I learned a few things about practising in this quite unique environment.

In addition to routine medical work, I was asked to give some health-related briefings to the crew, including a series on fatigue management and shift work. Outside the medical remit entirely, I was tasked with investigating a couple of adverse occurrences elsewhere in the ship, and formally writing reports on these to the Commanding Officer.

I was determined to take full advantage of all the opportunities available on a warship, managing to tick a few items off the bucket list by getting to drive the ship, fly in the helicopter, and hang on for dear life out on one of the ship’s fast little sea boats. I asked if I could spend some time in

Greg in Istanbul

every department of the ship, enabling me to peel potatoes with the chefs, repair headsets with the electronic technicians (thanks RGS, I can still solder), fold napkins with the stewards, hang out in the engine spaces with the marine technicians, and generally hear people’s stories while seeing what their jobs involved. Some maintenance of core military skills was undertaken, doing drills with the .50 calibre machine guns, live-firing of the standard rifle, and undertaking a whole heap of PT in 35-degree heat on a flight deck!

Recognising how important non-work activities are for personal and ship morale, I formed a guitar and vocal duo with a colleague, competing in the ship’s ‘X-Factor’ competition and performing a longer gig for the other officers later in the trip. We also plied our guitar partnership on Sunday mornings, leading a short open-air Christian worship service on the pitching, windy upper deck for any of the crew who wanted to attend.

The operational phase over, Te Kaha sailed to Cochin, India, where I was to leave the ship. Before I disembarked, I was awarded the New Zealand Operational Service Medal by the Chief of Navy, along with a large proportion of the young crew. The ship would continue on to a large multinational exercise off the coast of Australia before eventually sailing home to Auckland, but I got to fly back to New Zealand to my long-suffering wife and children (who were fortunately still speaking to me). Overall, this was a hugely enjoyable and personally challenging experience, as the next stage of a medical career which has veered a little off the beaten track and taken me and my family some 12,000 miles from Jesmond!