5 minute read

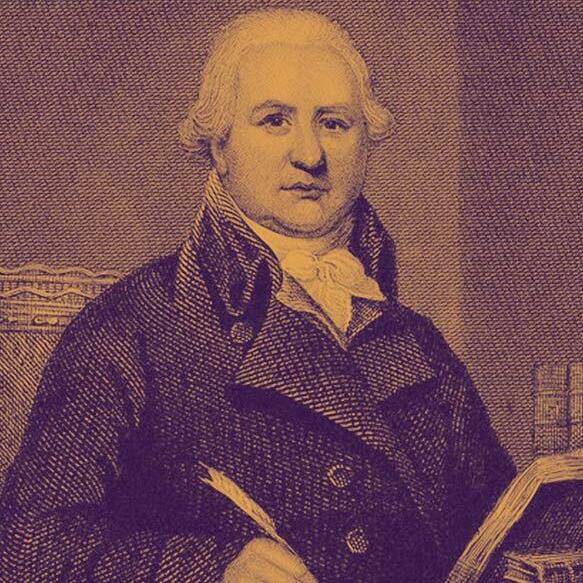

CHARLES HUTTON JOHN SMITH

CHARLES HUTTON THE GEORDIE WHO WEIGHED THE EARTH

BY JOHN SMITH (STAFF 04 TO PRESENT) RGS DIRECTOR OF PARTNERSHIPS AND FORMER HEAD OF MATHS

Advertisement

As former RGS parent, (The Viscount) Matt Ridley writes in his recent book, How Innovation Works, “…innovation is nearly always a gradual, not a sudden thing. Eureka moments are rare, possibly non-existent”

Ridley investigates this thesis in realms as diverse as Computing, Healthcare and Food, but it is in the context of Scientific innovation that his well-argued book resonated with me. In the history of Physics and my own subject of Mathematics, breakthroughs are almost always an iterative, collaborative process: a succession of great minds each standing on the proverbial shoulders of giants. It can take a veritable human pyramid of such giants to crack even the simplest of questions.

Think: ‘Why is the sky blue?’, ‘How did the Universe begin?’ or, more pertinent to this article, ‘How much does the Earth weigh?’.

It is the last of these questions that troubled the former coal-miner, school teacher and criminally forgotten Geordie genius, Charles Hutton. In the book, Gunpowder and Geometry: The Life of Charles Hutton, Pit Boy, Mathematician and Scientific Rebel, author Benjamin Wardhaugh takes us on a breath-taking journey from the coal-pits of Newcastle to the highest echelons of the British scientific establishment, taking in tutoring of Royal Grammar School students on the way. We learn of a man of innate intellectual curiosity: dare I say, someone who embodied a real Love of Learning and a true Ambition to Succeed.

Building on the work of Sir Isaac Newton, who had established the link between motion and mass in the late 1600s (the Universal Law of Gravitation), it was not until 100 years later that Hutton set about designing the experiments that would help to weigh the earth. Needless to say, he couldn’t place the earth on the bathroom scales. So, how was this feat to be achieved? Well, first of all, he needed to find an object big enough to displace a hanging plumb-line through its gravitational pull.

In 1774, he was in luck: the Reverend Nevil Maskelyne, Astronomer Royal, had found an unusually symmetrical and largeenough mountain in the Scottish Highlands: Schiehallion. Maskelyne was able to measure the angle of deflection of the plumbline in the vicinity of the gravitational pull of the mountain, providing a key clue on which Hutton could build his work. Four years later, Hutton used these measurements to calculate the density of the Earth, which he figured to be 4.5 times that of water, and surprisingly higher than the density of rock. The scientists were edging closer to the mass of the Earth, but it took Henry Cavendish another 20 years to finish the line of enquiry at his mansion in London.

Think: ‘Why is the sky blue?’, ‘How did the Universe begin?’ or, more pertinent to this article, ‘How much does the Earth weigh?’.”

Recommended Reading:

How Innovation Works, Matt Ridley (2020) is out in paperback

Gunpowder and Geometry: The Life of Charles Hutton, Pit Boy, Mathematician and Scientific Rebel, Benjamin Wardhaugh (2019)

Universal: A Journey Through the Cosmos, Brian Cox and Jeff Forshaw (2016) is an accessible place to start for the detail of the maths and physics behind Hutton’s work and those of his contemporaries.

History of the Royal Grammar School, Mains and Tuck (2016) is the definitive history of the school.

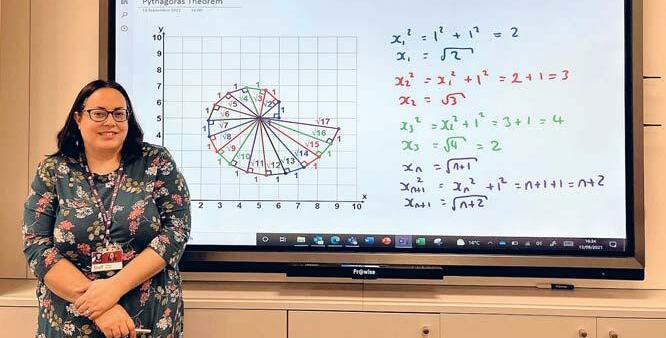

Sarah Sharp

The polar opposite of Hutton, an eccentric ‘man of independent means’, he devised a fiendishly ingenious contraption to measure the displacement of suspended balls via a series of pulleys, improving on Hutton’s density approximation in Schiehallion. As Cox and Forshaw note, “Hutton remained sceptical of Cavendish’s measurement until the day he died’. Inspired by Hutton, Scottish mathematician John Playfair took the baton and returned the Scottish mountains to refine Hutton’s original, crude, but surprisingly accurate calculation. As Hutton would later write, somewhat pointedly,

“…the preference, in point of accuracy, seems to be decidedly in favour of the large mountain experiment over that of the small balls.”

With modern methods, we must now concede that the Londoner was indeed more accurate than the Geordie, but there was not much in it! From Cavendish’s density number, the mass of the Earth could be deduced using what is now GCSE Level Maths to be 5.9 x 10^24, with the actual value measured as 5.97 x 10^24. Not a bad level of accuracy for the late 18th century!

As I learned of Hutton’s time as a school master in Newcastle, I was struck by the parallels between the educational landscape of the town then and my current mission to build partnerships between the RGS and local schools now. There is a long tradition of collaboration between Newcastle schools. In the Mains & Tuck History of the Royal Grammar School, we learn that through the late 1700s, Newcastle was home to a good number of private schools: ‘…at least fifty-seven private schools or academies have been identified as operating in Newcastle in the last thirty years of the century’.

Furthermore, ‘…one that gained a reputation beyond the town was that of Charles Hutton’. Hutton’s school was near the Grammar School’s then site on Westgate Street and ‘a great proportion of the Grammar School pupils attended Mr Hutton to learn Mathematics’.

Even after Hugh Moises’ modernisation of the curriculum in 1793, ‘students continued to attend private schools or academies for special subjects, such as Hutton’s for Mathematics’.

Having taken on the role of Director of Partnerships at RGS in January 2021, I am delighted and honoured to continue this spirit of collaboration among North East educators towards the common aim to raise the aspirations and attainment of students across the region, irrespective of background and means.

In the past year, we have been hugely excited to launch the work of our Physics and Maths Partnerships teachers: Tom Williams and Sarah Sharp. Tom and Sarah’s work is funded by the Reece Foundation, with each working partly in RGS, but mainly in the wider community. Tom’s CREST Award strand of work in local schools is very much in the spirit of the Hutton era: providing opportunities for gifted students to devise experiments and to test hypotheses in the context of local industry and innovation. One of his recent projects with students at Benfield school has been to design a Raspberry Pi-operated music player to work in the casing of Victorian Radios at Beamish Museum. While Hutton had to do without micro-chips and WiFi on his treks to Schiehallion, his spirit of enquiry, endeavour, collaboration and curiosity certainly lives on in the outward-looking, modern RGS community.