7 minute read

RGS Go Camping

from ONA 83

Tents, Trenches and Treks RGS Go Camping

In our new series about school camps we begin with Henry Spall’s memories of camps in the 1950s

Advertisement

Camping began at RGS in 1925. There’s an excellent review of these early days in the December 1950 issue of the NOVO magazine. The only camps that were not continued after the War were the weekend camps in the Tyne Valley, and the Whitsuntide camps in Northumberland and the Lake District.

At RGS during the 1950s, camping was still very popular. There were the May Race Week camps, principally in the Yorkshire Dales. The History camps were more leisurely, spent in widely-spaced parts of the country. During the summers there were camps in the Lake District, and the Isle of Arran. The Harvest Camps were a relic of the war years, and were spent in Lincolnshire and East Anglia. All provided hard grounding and character building for youthful minds.

I went to seven camps during my years at RGS. The best thing I can do is to try to give a composite summary of impressions of camping life from the memories I have. For the lower school students, Race Week camps were the introduction – mine were Wensleydale and Swaledale. Marshalled by the masters under the clock at Newcastle Central Station was the start of the adventure. The same scenario would occur for the summer camps in the Lake District and Arran. Carrying a bizarre collection of oversized kitbags, Bergens, haversacks, and some suitcases, about 30 of us would board the train to the destination. This was in the days before Dr Beeching’s decimation of the railways, when local rail lines were abundant and you really could get there from here. It was also the wondrous age of steam trains, which produced their hypnotic clacking on the tracks (as well as a recognisable fug in the carriage). It was also the time of individual compartments with three abreast, either side. We tried hard not to have any adults in the compartment, because in those days adults could be quite vocal and caustic about the behaviour of the young (who could be generally cowed by “authority”).

The campsite had been chosen so that we could walk to the farm field from the station. It was bordered by either a river or a steady-flowing stream. Inevitably we shared the field with cows. Once there we were organised by the masters and had to put up the bell tents – providing the truck had arrived with all the gear. The tents were British Army issue, with six people assigned to a tent. Digging the latrine trenches was an essential and immediate task (Louis Theakstone’s “Palace of Varieties”). The mornings always began with the masters who organised firelighting, cooking the breakfast (often porridge), and boiling water in the Dixie for tea. (We all swore blind that they habitually put bromide in the tea to assuage little boys’ excess hormones, but no one ever actually saw the dastardly deed). There is something fascinating and profound about eating breakfast outdoors and listening to sausages frizzling on the grill. I don’t know whether that makes our senses much more responsive or whether it’s nature and fresh air. After breakfast there was usually a quick service, kit inspection, and we would learn the plans for the day.

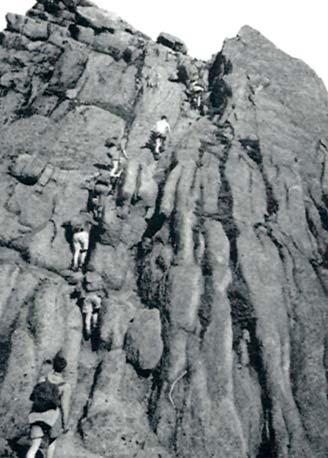

The day’s walking involved some nostalgic names. Great Shunner Fell, Rogan’s Seat, and the Buttertubs in the Dales. Goat Fell and Glen Sannox in Arran. Scafell Pike and Great Gable in the Lake District. As we left the farms and fields behind with their neat stone walls and the faint sound of the sheep, we seemed to be trekking up fells that had endless slopes of heather with never a summit in sight. But the sound of the curlews and skylarks kept us company, and we would often scatter the nesting grouse. For me, the day’s walk was the least enticing thing about camping. I was always lagging at the back, and was ever hoping that we would eventually be going downhill and could soon see the campsite. I remember the camp in Buttermere where we walked prodigious miles up and down during the day on a trek to Scafell Pike. I was never more exhausted in my life when I got back to camp. I had just enough energy to down a plate of stew for dinner and then sack out for the night. (On the same walk, a search party had to go out late at night because one of the masters, Tucker Anderson, had not returned. He was found safe at midnight on the top of a Pass). But there were always enthusiasts who were enthralled with endurance hikes –often climbing a few more hills just to fill in the day. In those days we didn’t have the luxury of Nike or Adidas trekking boots. We had leather boots with hobnail studs in the soles. Later on we were able to change the studs for rubberised commando soles. Half the weight but still clunky.

If the day were wet, the local bus service could be brought into play to get everyone to a nearby landmark – Bolton Castle or Richmond were favourites. Otherwise we used to put up with the rain if we were already out on the trek. Rain, especially incessant rain, played havoc with the sanitary arrangements. In Arran, where the rain turns up as lashing sheets of solid water, we had to be continually digging trenches around the tents to funnel the water away as the field turned into a quagmire. We had one “free” day, and you also got another day off if your tent was designated for cook patrol. Entertainment in the evenings was often provided by the villagers. The local male voice choir started us off, and we would respond with lusty Tyneside songs. Games were encouraged by the masters – football or bridge were popular – although most of us were usually too tired to take an active part, preferring to retire to our tents and scoff the goodies from the parcels our parents had sent us. In Arran we had the benefit of a small quintet of instruments – tea chest bass, guitar, banjo, mandolin and recorder. For further amusement we used to light a Flit gun to annihilate the midges. Remember, then there were no battery radios, no fancy cameras, and certainly no electronic playthings.

I went to three History Camps. These were different. Civilised. No tents, no latrines in the far corner of a field, no long-distance hikes. We were housed in Village or Parish Halls. We could sleep on cots. We went everywhere by bus or train. They were real learning experiences for we had high class guides who gave us comprehensive explanations in museums, churches, country houses and points of history. The camp at Bury St Edmunds was a significant event in my life. Aged 16 I had never been to London, so on my free day I went there. For someone who had spent all his life within 10 miles of Tynemouth, the thought of venturing to London was akin to going beyond the pale. I must have enjoyed it immensely because four years later I went on to King’s College, London. I do recall that I missed the last train back to Bury, and had to catch the milk train from Liverpool Street at four o’clock in the morning. At the Stratford camp I took advantage of the Memorial Theatre to see A Midsummer Night’s Dream. This was precisely one of the plays we had to read for the upcoming O Level exam in English Literature. It gave me a much better viewpoint of each character than reading through the play by rote.

No question that the success of RGS camping was due to the masters and Old Novos who helped out. They provided the motivation and energy to get us going and to see the day’s activities through. The Race Week camps were actually very good therapy to prepare the pupils for the exams that came in July. They provided exercise and camaraderie as excellent pick-me-ups before the final swotting for exams at the end of term, and O and A Levels. But in the long view, the RGS school camps provided a unique opportunity to explore the countryside and to be made aware of nature and history in all its aspects – in sun, rain, wind, and even snow. They provided us with standards of life different from those in our homes; they helped us to foster qualities of self-sufficiency; and to learn what it was like to live among others.

Henry Spall (49-58)