4 minute read

Medics on a High

from ONA 101

David Peberdy (99-09) on an unforgettable work experience in the ‘Land of the Thunder Dragon’.

Above: Punakha Dzong Below: Outside the Tradtional Medicine Hospital in Thimphu

Advertisement

In March and April I was on my medical elective, a period of time towards the end of medical school when students are encouraged to go abroad and gain work experience.

I chose a country that the world and I didn’t know too much about –Bhutan. I’m not sure I can blame Mr Newman (00-04), my Geography teacher, for not knowing much about this inconspicuous country. Although for a small country it has some international accolades to its name. Most notably the use of Gross Domestic Happiness (GDH) instead of GDP as a marker of growth. I think I learned about this concept the same day Mr Scott (05-11) taught us about the Big Mac Index in Economics. GDH is tied in with the country’s strong Buddhist roots –the dominant religion in Bhutan. Famously it was the last country in the world to introduce TV (1999) and, as far as I’m aware, is the only country that is a net carbon sink and has, as part of its constitution, a commitment to keep over 60% of the country forested for all time. Add to this, the name ‘Kingdom of Bhutan’, or if talking to Buddhists, ‘Land of the Thunder Dragon’, the country takes on a mysterious quality which makes it a very appealing place to go. The clinching factor in my decision to go was the relationship between

Chagri Monastery tucked into the hillside. A theme for religious buildings in Bhutan.

Monks playing at Phajoding Monastery overlooking Thimphu valley

Magdalen College, Oxford and the current King of Bhutan who was a student there. This meant the normal $250 per-day-per-person charge for tourists was waived. An opportunity not to be missed. Although I should say the $250 charge includes a driver, guide, accommodation, and main meals. It’s still not cheap.

The medicine itself was amazing to be part of and the doctors were incredibly welcoming. One of the biggest challenges was the language barrier, the national language is Dzongkha and is as hard to speak as it is to spell. Having struggled to get to grips with French and Spanish at school, as I’m sure Madame Sainsbury (80-05) and Miss Fitton (04-05) would testify to, trying to learn even basic Dzongkha proved a challenge. Fortunately, the doctors are trained in English and English is taught in schools.

We were based in Jigme Dorji Wangchuk National Referral Hospital in Thimphu, the capital of Bhutan. I was based in the emergency department, as this is a specialty in medicine that I have an interest in and I thought it would afford me the most interesting exposure to patients. It didn’t fail to disappoint. The first patient I saw was a young woman who had suffered an horrific dog bite in the early hours of the morning exposing her leg down to the bone. It was a gory start to what was by and large a fairly normal emergency department, with asthma, pregnancy, drunks, and mental health problems. All of which demand time and attention. The lack of specialty trained doctors is one of the biggest hurdles. This makes them very dependent on visiting doctors and neighbouring countries. A lot of complex surgical cases are exported to India at extortionate cost to the Bhutanese government. As they have a national health service in Bhutan this bill is footed by the government, which is incredibly generous, but certainly not sustainable. This is one of the reasons why visiting doctors can make a huge

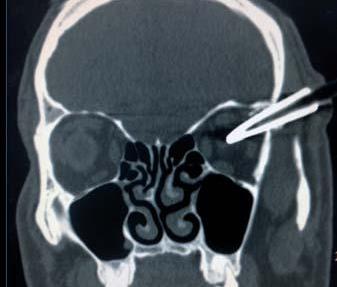

Bamboo Arrow CT scan

difference within the Bhutanese health system, and I would advocate going to any doctors or surgeons who want to take on a challenge. Another case that stood out was a gentleman who had been taking part in an archery competition. Archery is the national sport of Bhutan. These competitions bring with it drinking and celebration. This man had been drinking and dancing in front of the target (a 1m x 50cm piece of wood shot at from 120m away). Dancing in front of the target to taunt the opposition is commonplace and traditionally teams dance whenever the target is hit. Songs are also sung to represent love, enlightenment, and karma. The dancing can, unsurprisingly, end up badly. He was hit with a bamboo arrow in the temple. Remarkably he was fine and able to talk to me in the emergency room, just complaining of a, “Bit of a headache”. Fortunately, he came out of surgery with no obvious deficits. There are several of these cases a month, sadly not all are so lucky. Despite this, their enthusiasm for archery isn’t diminished.

Bhutan practices traditional medicine alongside Western medicine and uses it to good effect. Importantly, the two aren’t seen as mutually exclusive. Patients with sepsis do get antibiotics, not gold needle therapy, and patients with chronic pain can choose steam application rather than more pain killers. Traditional medicine is becoming less popular as Bhutan opens its borders to the outside world. I hope it isn’t stopped altogether as patients see huge benefits from it. If nothing else, my time there was a lot more pleasant on the nose than UK hospitals.

I want to say a huge thank you to the ONA and would endorse to readers volunteering in Bhutan through organisations such as Health Volunteers Overseas.