11 minute read

My winter window

from Sept. 27, 2018

Dracula vs. Frankenstein

stop. ... We don’t think we can wait to move forward with aggressive clean energy policy while a state with a lightly-staffed Public Utilities Commission and a legislature that meets only every two years hammers out the details of a complex and difficult transition. And we don’t think that the electricity market that results from this transition will benefit small customers like us or the environment.”

Advertisement

Many in the environmental community have subsequently withdrawn their support from the measure.

Another problem plagues Q3. Both it and a second ballot measure, Question 6, deal with energy, and both seek to implant their language in the Nevada Constitution.

The benefit to their sponsors is presumably to insulate their measures from change by the Nevada Legislature. But that’s not all it does. It insulates them from correction of mistakes or updating of language.

It’s not as though there is no example available of a mistake in the drafting of an initiative petition. In 2016, a ballot measure providing for background checks in some gun purchases not already covered by existing law was written to require federal checks and banning state checks. It turned out that the FBI declined to perform the checks for a state that had its own system, and state officials were unable to convince the feds to make Nevada a “hybrid” state that uses both types of checks.

As a result, the law Nevadans supported has never been implemented. Ballot measures sometimes do contain mistakes, and those errors are far more easily corrected in statutes than in the Constitution. According to the Guinn Center for Policy Priorities in Clark County, of states that have approved energy deregulation, not one has done it through constitutional change. All but New York have done it through statute, and New York did it through its regulatory body.

The Center warned that if Nevadans were to become unhappy with the results of Question 3, “They would have to repeal the constitutional amendment with another constitutional amendment. This would entail circulation of a new petition to obtain the requisite number of signatures to appear on the ballot and then passage in two successive elections.” Or the Nevada Legislature would have to process a constitutional amendment through two legislative sessions, and then it would have to be approved by voters. Either way, it would be a drawn-out process. Not everyone is comfortable with allying themselves with either side in this battle. On one side is the guy who tried to kill net metering. On the other is a guy who doesn’t want to pay his bills. But Question 3 is coming at Nevada whether residents like it or not, and it must be dealt with. Supporters of Question 3 say that predictions of unfavorable outcomes to its enactment are “speculative.” That’s certainly true. The effects of deregulation are never predictable. But their predictions of favorable results from Question 3 are, therefore, also speculative.

“Competition is good,” according to the pro-3 campaign’s website. “Don’t let a monopoly like NV Energy tell you otherwise.”

But there’s an underlying premise to that statement that demonstrates the unpredictability of deregulation—it assumes that deregulation promotes competition.

In 1978, Congress deregulated the airlines. Nevada’s Howard Cannon, who chaired the Senate Commerce Committee, tried to stop airline deregulation but was outmaneuvered by Ted Kennedy. The London Economist reported, “Cannon is almost alone in his skepticism. Sen. Kennedy brushed aside [Cannon’s] questions with an implied question of his own: What is wrong with getting lower fares for the public, no matter what harm it may do to the present system?” Kennedy went around the Nevadan and built support for deregulation in Cannon’s committee. Unable to stop it, Cannon retreated and said he would sponsor the bill himself in order to keep some control over the process.

President Carter signed airline deregulation on Oct. 24, 1978. It nearly destroyed the airline industry. Far from fostering competition, as sponsors had promised, it triggered a series of bankruptcies and mergers that put more than a hundred airlines out of business, including well-known carriers like Eastern, Braniff, Pan Am, Continental, Northwest and TWA. Two aviation experts reported that the losses that piled up equaled the airlines’ profits for the previous 60 years of passenger airline existence. No one brags any more about having helped deregulate the airlines—or about creating competition in the airline industry. There are a handful of big, national airlines left, providing lousy service.

In the 1990s, Congress deregulated the banking industry and Wall Street. President Clinton recommended it to a Republican Congress. The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act repealed the Glass-Steagall Act, enacted by Congress in the 1930s to keep banks out of the insurance business and prevent another Wall Street collapse. Congress also passed the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, exempting credit-default swaps from regulation.

Nevada’s U.S. Sen. Harry Reid reluctantly voted to repeal Glass-Steagall and later said he made a mistake. During the 2008 Wall Street meltdown, Reid said deregulation “paved the way for much of this crisis to occur.” The meltdown was so severe and the financial institutions involved so huge—Lehman Brothers, Bear Stearns, Merrill Lynch—there were those who said if they went down, they could take the United States with them. The ensuing investigating commission found deregulation “which effectively eliminated federal and state regulation” to be one cause.

The results of deregulation are seldom predictable.

There’s an example more analogous to the Question 3 debate.

During the 1990s and early 21st century, state legislatures deregulated their power generating markets in varying degrees at the demand of Enron, which wielded huge campaign contributions and pseudo-intellectual “studies” calling for deregulation. Half the states went along, including Nevada, where deregulation was something everyone at the legislature “knew” was needed. Nevada did it in electricity and gas. Consumer advocates who urged caution were ignored. (A 2007 Power in the Public Interest study of Department of Energy figures found that retail rates rose more from 1999 to 2007 in deregulated states than regulated states.) California partially deregulated in the same approximate time frame. Soon, the families of the working poor were being evicted from homes because their power bills shot out of sight. Companies shut

down, unable to pay suddenly astronomical power bills. Havoc spread across the West, particularly in the three Pacific Coast states, as blackouts and brownouts roiled society. Transcripts of Enron telephone calls laid out the frauds in detail. States like Nevada were even pulled into the act when California-generated power was sold to 2016 Nevada, then sold back to California at ridiculous prices, something that regulation

Democrats regained had prohibited. When it was all over, Nevada’s Valley majorities in both Electric Association had to pay Enron $14 million for electricity that the fraudulent houses of the corporation never supplied, and Nevada’s legislature, and the 2017 attorney general went to court against Enron. Even Gov. Kenny Guinn, a former utility legislature acted to president who believed in deregulation, was protect shaken by the experience and retreated from deregulation. net metering. now what? Initiative petitions were created to give everyday citizens a tool to be used against rich people, arrogant corporations and overbearing government. Instead—and particularly in Nevada where business lobbyists convinced the state to make petition requirements more onerous—initiatives are used only by the wealthy, corporations or powerful interest groups that can afford to gather the signatures. One risk of initiatives is that they will be used on issues of such complexity that the public will be at a loss on which side is right. The rise of modern public relations methods are particularly good at concealing the real intent of petitions. No one is campaigning on Question 3 with talk of exit fees, or regional markets, price spikes, interstate transmissions or stranded costs. Those are the kind of things legislators normally deal with. Instead, the campaign is about “choice” and “renewable energy.” 2017 We live in an era in which things no one expected have come to pass. Renewables are not only practical now, but their price has a group called the dropped dramatically. Does that mean it is time for Question 3, which would eliminate coalition to Defeat any ceiling on rates? There is a long line of Question 3 announced other corporations waiting behind the Sands, including Tesla, who say they are next. Does it had been formed to it mean that if we deregulate, Adelson’s oppose version of deregulation is the correct one? How can an ordinary voter even know what Question 3. that version—and its consequences—are? As with other instances of deregulation, we cannot know. We can try it, or we can leave energy policy to the Nevada Legislature. Ω

2018 Gov. sandoval began making preparations to implement Question 3.

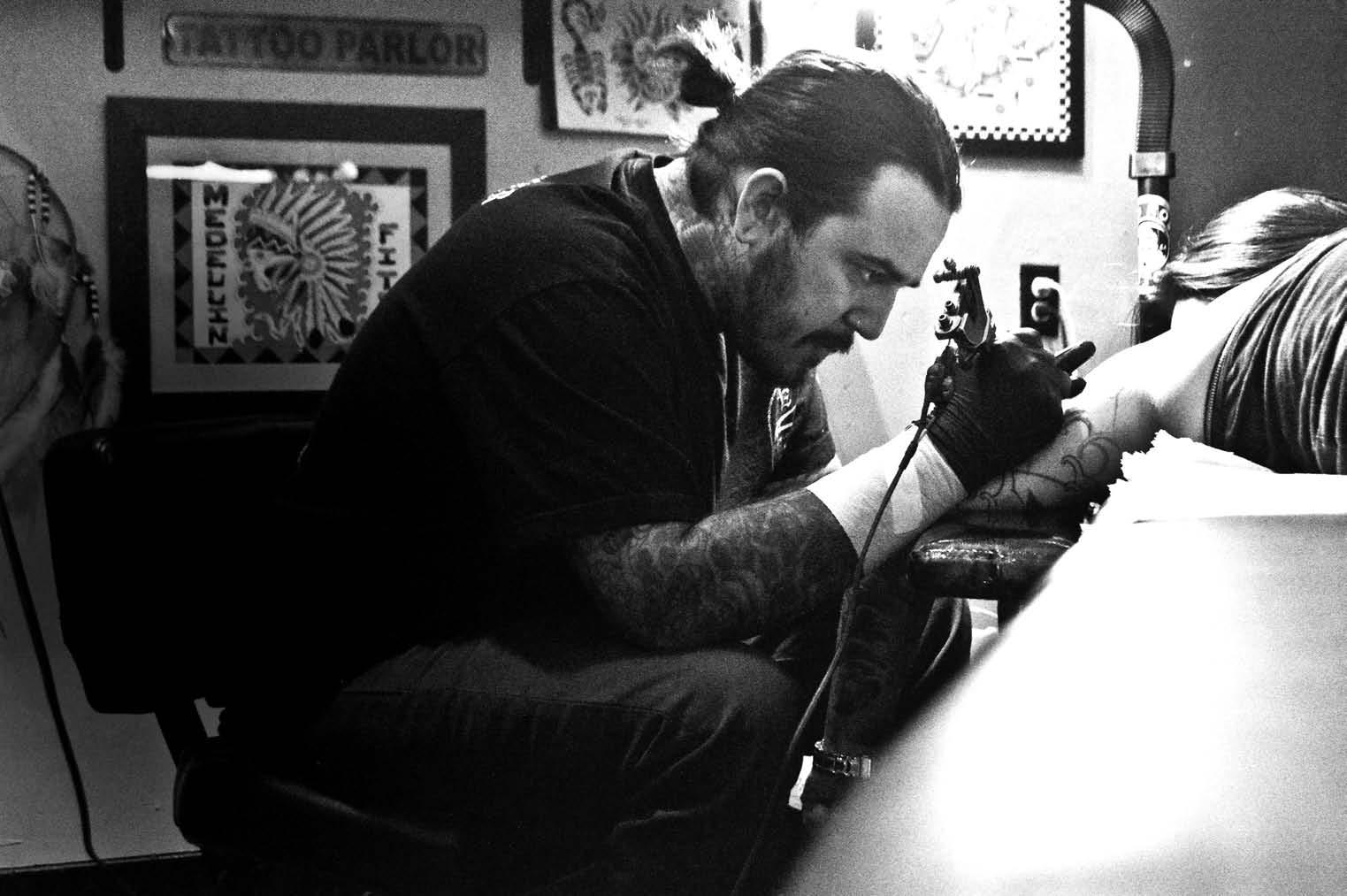

Tony Medellin works on Elizabeth Hebert’s sleeve in his studio space inside Lasting Dose Tattoo & Art Collective.

PHOTO/JERI CHADWELL

Skin

Tony Medellin was born and raised in Reno. The 31-yearold has been tattooing for 16 years, and now he’s a contestant on the 11th season of the Paramount Network show Ink Master, which premiered on Aug. 28.

Where’d you tattoo first?

It was this little shit shop off of Keystone. … I don’t know if I want to mention the name, though, because it was kind of a sketchy situation. And then after that, I moved to Los Angeles—worked in a friend’s practice studio for a couple months. I came back up here, and I started with Jon McCann at Absolute. So, Jon kind of took me under his wing. That was, I think, ’05, maybe ’04—no, 2005.

I saw a Facebook post you made back in May kind of explaining your decision to pursue this Ink Master thing. There was a comment from your mother that was just tear-jerking. Honestly, I’m reading it, thinking, “I don’t even know these people, and I’m tearing up.” She spoke about you taking a younger sibling along with you to talk with artists while she was working. Will you talk to me a little bit about that?

So, my mom’s a single mother. Me and my little brother have different dads. My dad’s still in the picture, but they divorced when I was young, so it was just kind of whatever. His dad bailed on him when he was a little kid, so, pretty much, I raised

by Jeri Chadwell • jeric@newsreview.com

A Reno tattoo artist competes on the national TV show Ink Master

him since he could walk. Yeah, I got him his first job. I actually just went and got him his first car today, like, I co-signed for his first car. He graduated high school. I bought a house so he could have his own room. He’s killing it.

And now he’s killing it.

He’s fucking awesome. … He writes music and plays piano. He’s a very cool kid.

Talk to me about your style. It seems it’s a ton of different stuff.

People are always like, ‘What’s your style? What do you prefer?’ I just like tattooing.

One thing I see in your work is a fairly solid outline. Not that I’d know, but that seems classic.

If it has black outlines, I’ll tattoo it. That’s my number-one rule. Everyone, when I was over at Ink Master, was like, “Will you explain why?” Think of it like this. You have a dirt lot. You just leveled it. You don’t do a cement foundation. You build a nice house on it. The house is going to look great right out of the gate, but, in the next five years, it’s going to start shifting, cracking—and it’s going to fall apart. But if you put a cement foundation on it, that holds everything together. That’s what a black outline is.

I wanted to ask about another thing you addressed in that Facebook post about Ink Master. It was your changing opinion about shows of its nature.

I’ll start from the beginning. Years ago, they asked me, “Would you like to go on the show?”—five or six years ago. And I was like, “No.” I mean, to be honest, a part of my response was, “Go fuck yourself.” And that was me being a tattoo elitist, thinking the industry was being ruined—blah, blah, blah. I didn’t know. I was just being young and stupid. So, finally, they hit me up again, and they’re like, “We’re going to pick someone from Reno. We’d prefer you. We like you, but it is what it is.” I realized at one point that tattooing is changing with or without me. I think the hardest part about being a tattooer is staying relevant. Tattooing is easy. It’s, “Will you keep up with the changing times?” Technology changes. Trends change. People change. I figured this was the best way for me to get ahead.

That’s an interesting point. I’ll draw a comparison to hair stylists. It’s an art to do it well, but it’s also an industry, where if they’re not keeping up on new techniques and tools and styles, people won’t come to them. Is that a fair one?

For sure—if you’re still using curlers from the ’50s, then you’re not going to get the wave of ladies who want their hair done using the new technology they saw on Buzzfeed.

Do you think the industry changing also has to do with the clientele for tattooing changing? I mean, a few decades ago, someone like me—a journalist in her 30s— wouldn’t likely be sporting tattoos.

Yeah, there’s a perfect example. The demographic changes all the time. I think tattooing doesn’t have a solid demographic. It’s just what’s popping that year. Oh, watercolor? OK, so know you’re going to have all of these fairly conservative ladies in their 30s and early 40s coming in because they saw a Buzzfeed thing. You’d be surprised. Buzzfeed does a lot of that shit.

It’s not just Pinterest then?

No. And, you know, my biggest pet peeve with people who talk shit on Pinterest, saying, “Oh, it’s another Pinterest tattoo, yet another Pinterest tattoo,”—Pinterest has been paying my bills for three years. … There’s a reason why it’s so successful. There’s a million