8 minute read

NEwS

from June 29, 2017

Rush to judgment

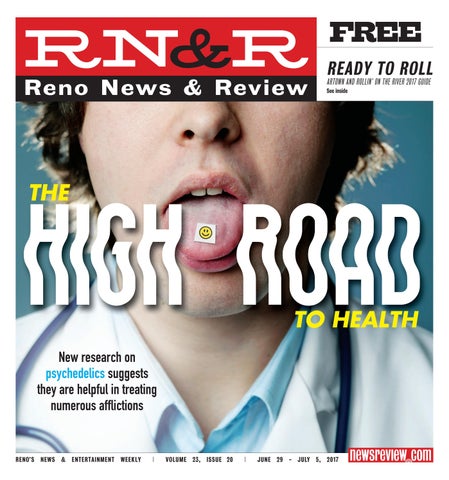

Like many illicit drugs, hallucinogens became illegal in Nevada mostly as a result of ignorance (see cover story, page 11).

Advertisement

During a special session of the Nevada Legislature in 1966, Gov. Grant Sawyer on May 24 expanded the call of the session to include legislation dealing with hallucinogens. The same day the Reno Evening Gazette—one of the two forerunners of the Reno Gazette-Journal—ran an editorial calling for ending the special session, and legislators themselves were also talking about going home.

“But the ... new item—a proposed law banning LSD and ‘other hallucinatory drugs’ could keep the legislation in session until next week … Law enforcement officials in Reno and Las Vegas supported inclusion of anti-LSD legislation because increased usage in the state is creating a police problem,” reported the Nevada State Journal.

The main police problem seemed to be that police could not make arrests.

As journalism has normally done since Virginia City and San Francisco gave the nation its first drug prohibition laws, the Journal reported on police reaction but did not talk to scientists or health care professionals about the issue. But reporters weren’t alone. With little research and less committee testimony, a measure was rushed through the legislative process, and, on May 30, both Sawyer and California Gov. Pat Brown signed the nation’s first state hallucinogen prohibition measures.

The speed was something of a surprise. In 1965, state legislators had tried to outlaw peyote and ran into a political buzzsaw—religious groups that used it in their ceremonies. Lawmakers backed off fast. They might have been expected to be more cautious this time, but they were not.

As it happened, on the same day Sawyer issued his expanded special session call, U.S. Sen. Robert Kennedy spoke on the matter at the opening of a congressional hearing. He was concerned about the sudden arrival of hallucinogens on the scene, but did not discount the role they could have in medicine.

“Suddenly, almost overnight, irresponsible and unsupervised use of LSD for non-scientific, non-medical purposes has risen markedly.” he said. “Such use carries with it grave dangers, and as LSD has become a problem, the possibility has arisen that public reaction will discourage and dry up legitimate research into any therapeutic use of LSD.”

Though even in May of 1966 it was plain that hallucinogens were a coming thing and that lawmakers needed to bring themselves up to speed. There is little evidence they did so. Instead, they reacted to episodic developments— particularly the 1967 release of a scientific paper by noted geneticist Maimon Cohen that found broken chromosomes in a 57-year-old man who had ingested LSD, suggesting that birth defects might follow use of the drug.

Journalism ran with the story with its normal concern for nuance and restraint, and soon legislators across the nation were passing more bans. It later turned out that the 57-yearold man had also ingested Thorazine and Librium, which do cause chromosome damage, but that bit of information never made it onto the front pages. And no generation of birth defect-afflicted children followed the hallucinogen use of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Meanwhile, research at the federal level unfolded pretty much as Kennedy predicted. The Food and Drug Administration curbed research on hallucinogens except by U.S. intelligence agencies. Pennsylvania medical ethicist Jonathan Moreno recently wrote in Psychology Today, “It’s high time to destigmatize psychedelics as objects of legitimate research for the good they can do.” At the Nevada Legislature, lobbyists and reporters schmoozed while legislators met behind closed doors in the last few days of the session.

PHOTO/DENNIS MYERS

Workers stiffed

Labor has bipartisan grudges

one group came out of the 2017 Nevada Legislature unhappy—working people.

“Not unhappy,” said one lobbyist. “They’re furious.”

OK, furious. And not just with Republicans.

“The Democrats kept dropping the ball,” said a Republican legislator. If he was taking some partisan satisfaction from the situation, he shouldn’t have. GOP Gov. Brian Sandoval and Republican Senate floor leader Michael Roberson are regarded as simply antilabor. Roberson is warming up for a run for higher office.

Republicans like to tell themselves that labor unions don’t speak for real working people, and while it’s very true that private sector union membership has dropped into single digit percentages, that doesn’t mean that unions’ issues don’t resonate with non-union workers.

There is, however, a difference between labor’s unhappiness with the two parties. It considers the Democrats incompetent. It considers the Republicans malevolent.

Sparks Tribune columnist Andrew Barbano, who has many labor union sources, wrote last week, “Legislative Democrats threw their ATM under the bus in the 2017 Nevada legislative session. … Democratic leaders chirp about victories but mutter a ‘therethere’ pat on the head to workers who got less than nothing.”

Barbano even suggests Nevada Democrats could face Democratic primary challenges if they don’t mend fences fast.

No one in labor is courting a public breach with the Democrats, but spokespeople privately make their distress clear. One labor leader said the Democrats managed considerably more deft maneuvers on behalf of other party constituencies than for labor.

“Women got what they wanted,” he said. “So did the LBGT community. But our bills were put on an assembly line.”

What he meant by that was that with bills dealing with some constituencies, the Democrats gamed timing and tactics, often forcing Republicans or the governor to deal with them, backing Republicans off or avoiding vetoes. For instance, late in the legislative session, the Democrats plucked the content out of a vetoed bill dealing with insulin and dropped it into another bill with a slight change, then sent it off to Sandoval a second time. This time he signed it.

But when labor complained about their bills, expecting party leaders to hold some bills for the closing days when they could be negotiated, the Democrats instead sent them straight to the governor, who vetoed them. Where, asked the unions, was the cleverness Democrats showed on other issues?

“They gave him [Sandoval] a reason to vote with them, but not on our bills,” said that same labor leader.

Sandoval has been freer with his veto than any other Nevada governor except his immediate predecessor, Jim Gibbons. But where Gibbons used the veto to stop bills he had neglected to watch during the session, Sandoval uses it to “micromanage,” as one legislative staffer described it.

“This is an unusual use for the veto,” she said.

Roberson’s alleged role is that he held Sandoval to promised vetoes of nearly all labor measures. If so, they were among his few victories—“the number one loser of the session,” one lobbyist called Roberson. In a June 13 essay in the Reno Gazette-Journal, Roberson wrote that Republicans “prevented every attempt to roll back our cost-saving reforms from 2015.” Many of the bills Sandoval vetoed would have undone bills from the 2015 session.

Labor-related measures vetoed by the governor include:

A.B. 175, clarifying the meaning of “health benefits” in the state constitutional minimum wage requirement.

A.B. 303, banning the use of commercial prisons by the State of Nevada.

A.B. 350, allowing worker organizations to be included in employee orientation.

A.B. 154 and S.B. 173, providing for payment of prevailing wages on some projects.

A.B. 271 and S.B. 356, dealing with collective bargaining.

S.B. 106, providing an increase in the state minimum wage.

S.B. 196, providing for employee sick leave.

S.B. 357, dealing with use of apprentices on public works projects.

S.B. 384, providing for confidentiality in some public worker pension records.

S.B. 397, dealing with penalties for gender-based discrimination.

S.B. 416, dealing with training and apprentices in medical marijuana dispensaries.

S.B. 427, dealing with size of railroad train crews.

S.B. 464, dealing with labor agreements in renovation of the Las Vegas Convention Center.

S.B. 469, dealing with the percent of local government ending fund balances that is subject to collective bargaining.

On the other hand, the Nevada State Education Association—which often has different concerns from other unions—was pleased with the Democratic performance in shutting down a program that paid $5,000 grants to parents to take their children out of public schools. The Democrats ended the program by defunding it, all but daring Sandoval to veto the state budget. The governor decided he did not want to put the whole budget at risk, in spite of Roberson’s constant “No ESAs, no budget” threat. ESAs are “education savings accounts.” Paradoxically, at a time when relations are tense between Democratic legislators and labor unions in Nevada, national unions are aiding Democrats in targeting

“Legislative Nevada’s GOP senator, Dean Heller, on his Democrats threw vote on the Republican health care measure. their ATM under The AFL-CIO began an ad campaign on June 23 in Nevada the bus.” and four other states where senators’ votes Andrew Barbano appear to be up for grabs. Columnist The other four are Alaska, Maine, Ohio and West Virginia. Rutgers labor studies professor Rebecca Kolins Givan told Bloomberg News that the AFL offensive could be particularly effective in Nevada because of the strength of the Culinary Union in the state. “It’s become very politically active and highly mobilized,” Givan said. Ω

Newcomers

Summer students were going through orientation at the University of Nevada, Reno this week. This group was being briefed on the steps of the UNR library.