7 minute read

NEws

from June 1, 2017

EddiE Scott 1928-2017

Eddie Scott arrived in Reno in 1950, when the city had just 32,497 residents. “There were signs saying they didn’t want colored trade,” Scott told reporter Ed Pearce in 2011.

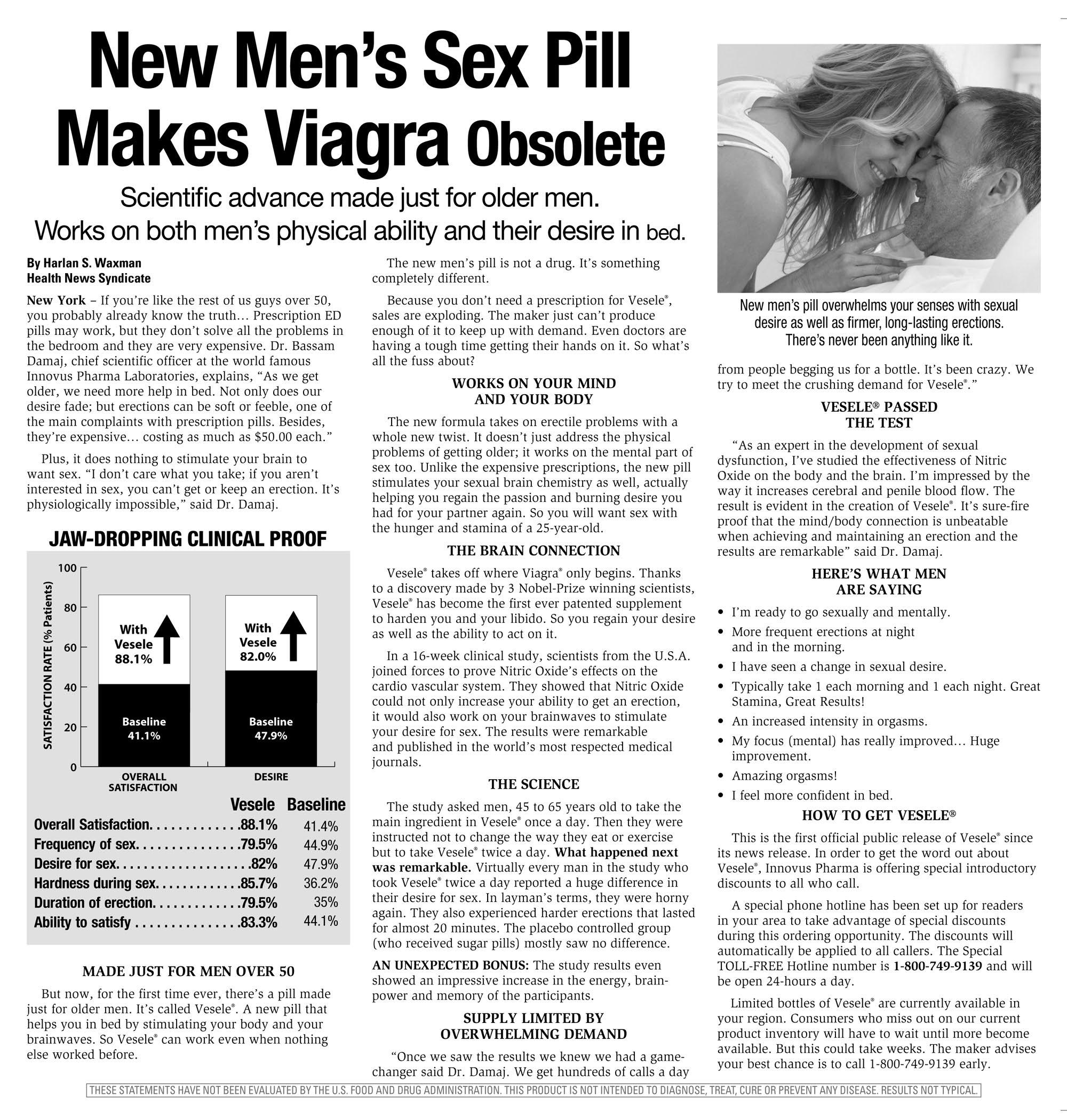

Advertisement

Scott arrived looking for work. He departed Reno for a time to work in nearby Herlong where he reportedly first became involved in civil rights. He served as Reno-Sparks branch president of the NAACP in 1961-64 and 1967-68. He worked to win enactment of equal rights legislation in the Nevada Legislature. In a 1961 wire to Nevada’s congressional delegation and President Kennedy, Scott described conditions for blacks in the state: “FHA discrimination everywhere. Negro service men suffering. Seventy percent relegated substandard rentals.”

For 12 years, Scott was director of the Race Relations Center in Reno. Begun with seed money from feminist leader Maya Miller, the Center dealt with the problems of daily life for low-income people of any color—jobs, housing, rights. Scott fought constantly for funding to keep the Center alive, tapping contributors and governments at all levels. Funding from a now-defunct federal program, the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA), made life easier, but the details of administration caused friction with those who oversaw the funds, often leading to public battles county officials. At one point, County Commissioner Dick Scott advised the employees of the Center to seek other jobs.

Elizabeth Gower Woodard, Scott’s aide at the Center, was one of those workers. She said he kept the Center going “on a slim budget. He got small grants here and there, like the one from Maya Miller, and small donations. But he was very smart in taking advantage of government programs, too. I was a CETA employee, and his association with CETA worked well for Mr. Scott.” Strain of fundraising and the work took their toll. Woodard said, “We tried to help everyone who called or came through our door. Mr. Scott was brilliant in finding partners to help people, many of whom had been denied help from agencies specifically designed to help them. It was maddening sometimes, but Mr. Scott just carried on with a quiet dignity.”

What many of those who faulted Scott’s performance never knew was that he was illiterate. One of Woodard’s functions was to read office materials to him. His numerous accomplishments were achieved in spite of this drawback. Those who stumbled onto his secret were often disbelieving.

In 2015, Scott was named a “Distinguished Nevadan” during a University of Nevada, Reno commencement. An NAACP branch award is named for Scott and his colleague Bertha Woodard.

Scott was not voluble about his pre-Nevada life. He was born June 19, 1928. He reportedly arrived in Nevada from Louisiana, though whether he was born there is uncertain. He died last week in Seattle. —Dennis Myers

Progress in protecting the clarity of the lake is under threat from climate change. GeOFF sCHLADOW

Clarity undercut

Climate change does its thing at Lake Tahoe

For decades, those who love Lake Tahoe have fought for its clarity, the quality that helped make the lake famous and lured people and money. There have been periods when progress was steady, and there are those dismaying declines that cause scientists a pit-in-the-stomach feeling that they are losing ground.

About the turn of the century, there was a sense that a corner had been turned, when gains in murkiness in the lake water more or less halted. In the subsequent decade and a half, there have been regular, favorable clarity readings that have encouraged all the players in the basin. But now, there have been declines in clarity once again.

For much of the battle, the issue was man’s impact on the basin itself. But the planetary problem of climate change has also been making itself felt, and it is more difficult to combat. On May 18, the Tahoe Environmental Research Center at the University of California, Davis reported, “The decline in 2016 is the second year in a row in which the effects of a changing climate have impacted clarity. However, the causes of the decline in each year were different. In 2015, clarity was reduced by relatively warm layers of turbid water entering near the lake surface. In 2016, the clarity was reduced by the early onset of spring, favoring the growth of light-blocking blooms of very small algal cells.”

The environmental health of the lake basin has been the responsibility of the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency (TRPA) since the mid-1960s, but it has dealt with direct human impacts on the basin. How does it deal with a planetary problem?

“Climate change certainly complicates things for Tahoe and for all freshwater ecosystems globally,” said TERC director Geoff Schladow by email. “Local officials and citizens have a limited effect on stopping climate change, but what is important and very possible is to adopt mitigations to climate change that will offset its impacts.”

“It certainly does complicate the task of restoring the Lake’s historic clarity, but the good news is that we are seeing evidence that the actions partners in the basin have taken, to date, are working,” said TRPA analyst Dan Segan. “We have always known that the lake is [a] very complex system, and the two states have built an adaptive management process that continually incorporates new information. In this regard, we are fortunate to work closely with a strong academic community that is committed to dealing with emerging challenges.”

The TRPA considers clarity “the iconic indicator of well-being” of the lake. Clarity was at about a hundred feet when the agency was created, meaning that is how far below the surface someone could see. Thereafter, during the 20th century, clarity fell into the 60s, then began recovering about 2002. On one celebrated occasion in January 2012, a level of 95.1 feet was recorded.

Summer clarity last year was just 56.4 feet, a 16.7-foot drop in a year. Cyclotella, a small photosynthesising algae about the size of a human hair, is believed by scientists to have thrived in warm summer water, helping to cause the decline in clarity. Lake Tahoe, famous for its alpine cold water, last year experienced record high water temperatures.

Algae has always been at the heart of efforts to protect the clarity of the lake. Last year Schladow put out an appeal for old photos of the lake that might help the scientists chart the presence of algae in the pre-1968 years. 1968 was when clarity measures began.

AppeArAnces

Will the introduction of new climate factors be a steadily increasing threat to the improvement that has occurred in the lake basin?

“What we are finding is that climate change is not ‘steady,’ but rather a highly variable factor,” said Schladow. “Yes, it will always be present, but, as I said before, there are mitigations. One of the threats from climate change is the reduction in mixing, which may threaten the renewal of oxygen at the bottom of the lake. One way to combat that is to increase the lake’s resilience to withstand long periods—possibly decades—without

mixing. This requires even greater focus on nutrient control as a way to reduce algal growth and ultimately to reduce the lake’s oxygen demand. “Another promising approach is new, innovative approaches to removing some of the invasive species that have disrupted the lake’s natural food web. Preliminary research has shown that restoration of the native food web “Climate can greatly improve clarity. This dual approach change certainly of external sediment and nutrient control, complicates things for combined with internal food web restoration Tahoe.” offers great promise.” A group called Geoff Schladow Hydrolic engineer Tahoe Public Art said it is going to put a floating sculpture on the lake to promote “awareness” of the lake’s problems, but if reaction to the UC Davis report is an indicator, awareness is not the problem. An Associated Press piece on the report ran in newspapers across the country and even overseas in places like India. Lack of action seems to be more the problem than lack of awareness. Ω

History

Wildflower Villiage is now rubble. The artists’ colony, made up of three 1950s-era motels on West Fourth Street (the former U.S. 40), was the project of Pat Campbell Cozzi, who put an art gallery, gift shop, rooms for rent, hostel, bicycle rentals, theatre, workshops, classes and coffeehouse all into it. Penske truck rentals helped pay for it. She kept it going for more than two decades.