9 minute read

to sea cocktail. happy hour.

the headwaters of a river - edible herbal plant, (like minty yerba buena - the plant of pre-colonized San pebble of granite, sourced

(perhaps befriend a beekeeper)? sea where the river lets out.

Advertisement

Take a slow drink.

Friant, California is a small town that maybe mostly operates around the dam. It is hot, 100 degrees, and the water of the San Joaquin swells at the base of the dam to a temperate lake with motorboats and geese. The granite basin floods and crumbles. Here rock is most visibly in a state of decomposition. The shore along the lake, a river swollen at the thigh, is crumbling granite boulders and large particles, like a confetti party of feldspar, quartz, mica - the composition of a mountain disassembling.

Along the water lines the sediment is sorted by weight, the fine magnetite eddies around the waveline, the flecked mica in river patterns strata-ed above that, and then the coarse crumbles of granite - like a high montane boulder field in miniature. A stratified aerial view of the movement of the grains this season, sorted according to weight and size, by the lakes lapping waves.

We’ve flowed hundreds of miles, carried life, waters and grains, the decaying bodies of plants and animals. Everything muddies by now. Golden mica glints in the sediment-heavy and stuck water.

Dams are traps for water, but also for sand. Here, the mountain sands experience a first stoppage in their source to sea journey.

In the town of Friant I can see the dam from the other side, a high castle wall, which in the right season, waterfalls down to regulate lake levels.

After the containing dam wall and before the release of the river waters back into their true bed, comes a split and a siphoning off of waters to the Madera and Friant Kern Canals. These two irrigation aqueducts serve the industrial farming of Central Valley. At times, the dam and these thirsty channels run the river dry for 50-60 mile stretches at a time, affecting whole ecosystems.

Gary Griggs is a professor of Earth Sciences at UC Santa Cruz who studies coastal erosion. I ask him about the stopped up rivers and sediment budgets and he says the sand we lose to Central Valley river stoppages don’t necessarily cause direct cuts to Ocean Beach’s sediment income. Ecosystems are not always so simple or so cause and effect - making it easy to ignore & hard to see. The river flows after a dry section and picks up all the load its force can handle and erodes out the river bed in that place with quickened force.

The beach, a skin, a river bed, a soil layer erodes and accumulates and devours itself whole by water, by wave, stuck to sticky traps in currents and the sweat in the crook of my arm. I get in the river and watch the dam. I walk on the highway and look down into the Madera Canal. It flows themepark aquamarine, the river black and heading into Central Valley. It is so hot, 100 degrees, and everything is borrowed up, until almost not at all.

Visit a dammed river’s lake (take a pen and paper.)

Friant Dam and Lake Millerton are one possible example in California. Fill yourself (your shoes, hands, pockets, hair or....?) with sand from its lake. Wade into the water, as you like.

Take notice of what you feel here? heavy feelings, stuck feelings, interrupted flowing or something else maybe?

Closing your eyes is nice. Breathing is too. Try some imaginings, maybe the brief & clumsy movements of billions of scattered, sloshing grains - imagining you are one of these too, bumping around minutely with the lake water waving, but not going anywhere much. Just a slight circular swirling, slow water eddies you around.

Stay this way for as long as you like.

From here, in this stuck position, write a letter to the riverjust whatever is on your mind.

A friend, Christine Lee, goes with me in search of the river again. 85 miles northwest-ish of Friant and 112 miles from where the San Joaquin yields into the San Francisco Bay, lies a small pocket called Great Valley Grasslands State Park. It’s August and hot like a desert.

By creeping off trail, poking our way through tall scratchy grasses, and carefully coming over a downed barbed wire fence, we find the river and can touch it. Here, in this place, it is 6 feet wide and 1 inch deep. Its movement is imperceptible. There is hardly any water in this river. I wonder how close we are to one of the official dry spots. The river and ourselves are far from the energetic mountain scene with tumbling grains of crystalline granite in fluid decomposition. We poke our toes in the mud, silt flumes around feet and mud sucks us in, but just a little, and mica waves its sparkling hello.

I mention the metaphor of sediment budgets that Gary Griggs shared. Christine is marveling at the golden, black flecks of mica glinting in the sun. Market-driven modes for getting people to care don’t seem all that interesting or useful to her. She’s focused in on the lives being lived in tiny submerged zones and advocates for amplifying the less visible.

How to think like a mountain? How to know like a sand grain? For now, we greet this sandy layer of granite pieces - signs from a familiar geological friend.

The Great Valley Grassland is a floodplain that preserves several species of native grasses and a shrubland ecology that is unique to a healthy San Joaquin floodplain. This tiny fragment is a preserved island of what used to be a continuous land of riparian plenty and home to San Joaquin pocket mice, giant kangaroo rats, hares, rabbits, California ground squirrels, gophers, grizzly bears, gray wolves, coyotes, mountain lions, ring tails, bob-cats, San Joaquin kit foxes and over-wintering migrating birds by the thousands.

Islands of preservation like this one have a ripple effect from source to sea and enough islands can eventually become long corridors, as restorationists like to say, and enough corridors can eventually become a continuous place again -- if we decide to try.

It turns out that those 60 mile dry spots in the San Joaquin River became a stain on public consciousness. In 2006, the San Joaquin River Restoration Settlement was established, ensuring that the river flows in critical spots to ensure the passage of life. Sagely, salmon are the selected keystone-species here. Providing for their habitat needs means allowing rivers to flow from source to sea. A claim which means habitat growth for everyone from sand, to native grasses, to kangaroo rats, and water dependent farms of Central Valley.

I write to the San Joaquin River Restoration Program to see about the current river levels and flow in the summer of 2018. Their response is a mix of imperfect fixes, slow bureaucracy and hopeful ways forward with collaboration between restorationists, state politicians and farmers. In short, they say that the section of the river from the Friant Dam to the confluence with the Merced River (in Ferry Hills, CA) will be kept flowing except during critically low years, in which case small parts of the river may go dry briefly. It’s imperfect progress, but it’s good to get started somehow.

A few miles down the road at Fremont’s Ford Boat Launch, the river widens and reaches darker depths. People are fishing, boats are floating.

This river, full of water again, snakes 100 miles more up to the delta, but until then, there are few places to be with it - a few roadside fishing spots, a boat launch here or there. Really, it is still sitting behind a patchwork quilt of privatized farms and seeing the river along this stretch is real hard unless you’re doing so by boat. You can do this theoretically, since the river bed is public no matter the state of the land beside it.

Industrial farming causes this lack of connection to the river. It’s a weird design and too big of a wormhole so, for now, I’ll try to re-orient to the slow millenial tumbling of grains: quartz, mica, feldspar.

A clear and yellow grain slowly turns under itself after days of water drifting over. The top-heavy and miniscule peak finally persuaded to collapse and roll over - in a year an inch. A black and glassy mica pixel piles up alongside the clear and yellow one, many years later -- silently streaming on the scale of millenia.

There will be a meeting at the sea later this year. I will see these grains or perhaps their (much) older counterparts. Almost there. Pacific intentions. I can feel the oceanic wind poke holes through the dry air of the valley floor.

We drive back by car - a mobility that is stunning by comparison, a fast romance that misses the point. I see a flash peripherally - a red tailed hawk lands and is perched atop a powerline eyeing a gopher. Driving west feels luminous like floating into the sun, glowing above the coastal hills, shimmering grasses expired for the year. Everything is golden, bursting or burst already from the profusion of light and heat and waterless days.

Pay a visit to a Delta ~ collect a pile

Dip your hands in the delta’s river.

Starting with the tips of your fingers. Hand slide your hands into the water. of liquid.

As you go, close your eyes and let to you about where it has beenvalley, and now resiliently, affluently, into the delta. for as long as you like.

Your hands are coated in this water

Coat your river hands with sand

Sand is like skin because it is the protective layer .... land from the forces of the sea. The particles cling and A crust of granite, feldspar and mica safely

Through the day, try to protect this skin around skin. Hand in pocket, embark on a careful

Write about what goes right and of river sand. Set it aside for later. Slow. perpendicular to the water’s surface. Slowly Letting it surround your skin in a perfect coat the water transmit some images a mountain waterfall, the headwaters, the Sit here taking in river images and its journey. Handshake. from your pile. Sand skin. the porous membrane that buffers the bedrock harden, mineralizing around your hand. wrapping your skin. protection. Sand on hand. Sand as Hand as land. anti-erosion day. what goes wrong with this experiment. a mercurial and relentless sea without becoming it.

The wind is from the ocean and the land - powerful and chilled like the Pacific and hot like Central Valley. The water is salt and also fresh. This is a place of mixing and convergence.

The San Joaquin River gives way and meets with the Sacramento and also the backwash of the Pacific Ocean, then into the oval chamber of the Bay. All this but not yet, we’re still at the meshy Delta place.

The Lange’s Metalmark butterfly is an islander. The only place it ever lived in the whole world was the Antioch Sand Dunes -- a 55 acre range of land beside the San Joaquin River just before it becomes the bay. The land here was sand dunes. They were 50 feet tall and now they are not dunes at all. Now, they are a sandy covering on a steep bank and a small bowl of a valley covered in sand and encouraged native plants.

The host plant for the Lange’s Metalmark butterfly caterpillar is a specific kind of buckwheat plant with long spindley arms that reach 2 ft above the little paddled leaves - Eriogonum nudum psychicola. Small pompom buckwheat flowers, yellowish and modest, adorn each arm. This scarce plant, who’s seeds rely on weedless sandy expanses and coarse soils for germination, is the only one that can sustain the lifecycle of a Lange’s Metalmark. With the endangerment of the sand, comes the diminishment of buckwheat and the loss of the Metalmark. This butterfly neighbor is listed as critically imperiled.

No sand, no buckwheat, no butterfly.

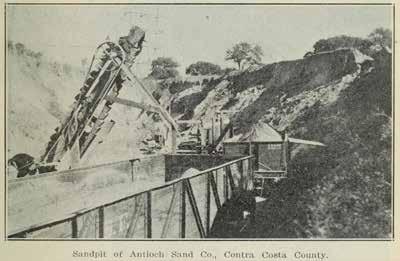

In 1903, the Holland Sandstone Brick Company opened in Antioch, California. The company relied on the Antioch Dunes’s vast riverside deposits. They mined sand from the dunes as fill to forge the brickwork.

In 1906, after San Francisco’s earthquake, appetite for construction materials boomed and bricks were especially coveted because they couldn’t burn down like so many redwood victorians had. The sand of the Antioch dunes was overmined. The dunes were flattened during that period and the Metalmark population declined alongside a San Franciscan building boom some 50 miles away.

We’re in a time of deficit - sand shortages the reality, even though sand is always seen in a multitude. This is bookkeeping on the millions of years scale - geological time’s accounting. Maybe we can understand how to budget if it’s in the language of the market, but can’t we feel love some other way?

The river carries the pebble, tumbles and saltates it, rounds jagged edge, diminishes its size until it is between .0625 and 2mm, at which point, it can be scientifically called SAND, be it decomposed granite or a sack of flour. The sand was once a landslide, a boulder field, a thing labored upon ceaselessly and completely by non-human workers until it became the size of a small grain, a geological seed.

The Antioch Dunes Refuge Manager, Louis Terrazas, says that they are rebuilding their dunes with sand dredged out of the San Joaquin river bed by the Port Authority of Stockton. The natural sand accretion becomes a hindrance to shipping, clogging underwater lanes. Here, a compromised trade deal was arranged. Through an oddly human cycling of resources, a living shoreline is being created.

It is imperfect, but perhaps, ecological restoration can be an act of mimicry and mimicry can be an act of relation and care. Re-building places can offer a neighborly gesture that doubles as a multi-species survival strategy emerging creatively from the ruins.

What was here and how can we mimic the conditions of an ecosystem before it was used to the ground? Can we get Metalmarks to move back in to their sand island town?