19 minute read

Building around people

Geoff rey Makstutis, Subject Lead for Construction and Art and Design at Pearson, off ers an opinion on ethics and asks ‘Who are buildings for?’

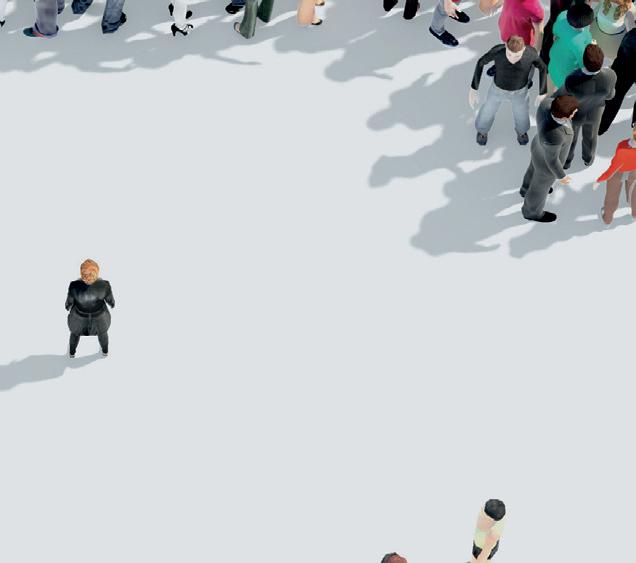

IMAGE: SHUTTERSTOCK Open nearly any architecture or construction magazine or visit their websites and you will see new buildings. These may be shiny, exciting, big, detailed, fi nely craft ed – even iconic. What you are less likely to see are people. It would seem that we are to understand buildings as things that exist in the landscape or the city and that they are best understood (and enjoyed?) as an image.

From an aesthetic point of view, it may be understandable that a photo of a building or interior can bett er show the design when there aren’t bodies in the frame. However, there is an underlying issue that buildings are oft en designed and constructed with, in my opinion, very litt le consideration of the users – people.

Having spent a good deal of my career teaching and acting as an external examiner in architecture and design at schools and colleges around the world,

I can att est to the fact that this absence of people is endemic. While there are a handful of programmes that have placed people at the core of the subject, there are far too many instances – seen in degree shows – where drawings and models are devoid of any human presence.

I would argue that the design, drawing and modelling of buildings without people is the fi rst step in a chain that leads to poor experiences in our buildings, prioritising cost over quality, and even the potential loss of human life. Perhaps that sounds extreme, but when we focus on the building rather than those who will use or inhabit the building, it becomes easy for human factors to be ignored. Furthermore, with the building as the primary focus, issues of cost, effi ciency and regulatory compliance have a very diff erent context.

No joke

I fi nd that even our regulatory frameworks are subject to this absence of the human. For example, of the 430,000 words that comprise the current Approved Documents of the English building regulations, the word people appears just 175 times (that’s about 0.0004%). The words person or persons appear about 313 times (0.0007%); however, these are oft en referring to the person(s) undertaking the building works, so not relating to the user of the building.

Building regulations can be viewed as minimum standards that must be met to ensure compliance. There is litt le sense of quality of experience or inhabitation being expected. Health and safety are the primary aims of the Building Regulations, but these are almost solely based on physical safety.

What of emotional wellbeing and mental health? At the Conscious Cities Conference in 2017, architect Alison Brooks said: “If science could help the design profession justify the value of good design and craft smanship, it would be a very powerful tool and quite possibly transform the quality of the built environment” (bit.ly/ABGreatDes). Research has shown that there is a link, forged within the hippocampus, between our brains and the spaces we inhabit. The need for the design of buildings to do more than meet minimum standards is both psychological

and physiological; and the two are intrinsically linked.

For many years, health and safety regulation has been seen as either a necessary inconvenience (creating the need for more documentation to support a bureaucratic process) or the punchline of a joke (‘health and safety gone mad!’). In both cases, these att itudes reveal a fundamental lack of understanding about the position of people in relation to health and safety. When we see it as a process, we move the focus from the aim to the necessary actions that defi ne the procedure. And it is oft en this focus on the necessary actions that leads to outcomes that become the punchline of the joke. The joke is not about human health or human safety. Rather, it sees the absurdity that can result from a process that has become too focused on itself.

Perversely, many of the most absurd cases of health and safety are actually urban myths. Such stories make wonderful tabloid headlines but have oft en been found to be either false or wildly inaccurate. Health and safety legislation is necessary and it isbenefi cial. In fact, since the introduction of the Health and Safety at Work Act in 1974, there has been an 85% estimated reduction in the instance of workplace fatalities. The construction industry workforce has been one of the groups for which this change has been dramatically positive.

Conveyor belt

To be clear, however, there is a diff erence between being safe and being healthy. Furthermore, there is a diff erence between health and safety at work and the way in which health and safety informs the design and construction of buildings. I would suggest that while health and safety at work has continued to make improvements in the wellbeing of those who construct our buildings, health and safety as presented in the Building Regulations has encouraged a further separation between the material aspects of the structure and the process of construction, and the people that will live and work there.

The horror of the Grenfell Tower fi re on 14 June 2017 is one of the starkest representations of how our process of design, construction and regulation – with litt le emphasis on people – leads to the worst of all outcomes. As the public inquiry continues, we are learning more and more about the string of failures that led to the disaster. For example, during questioning, one of the senior builders for the refurbishment of the Grenfell Tower stated that “we didn’t have the expertise to check whether design complied with regs” (bit.ly/AJGren). From this, and testimony by the design architects, it would appear that no one in the design and build process had the knowledge or took responsibility for ensuring that the

regulations could be met by the proposed cladding or insulation designs.

While I cannot, and do not, claim that the reason for allowing this string of failures is cost-related, it is not too diffi cult to imagine that the various parties might have considered the potential cost of employing suitably knowledgeable consultants (to check design drawings, specifi cations, etc) and the potential delays caused by undertaking further checking. This would have contributed to a decision to proceed without properly reviewing the designs for compliance. Of course, this is just my opinion.

In the wake of the Grenfell inquiry, there are calls for changes to a number of diff erent regulatory frameworks, which aim to make the process more robust, secure and reliable. In the move towards developing new standards and new processes, we have an opportunity to put people into the foreground. However, I fi nd that the recommendations of the Hackitt Report – while recognising some of the fl aws in an overly complex regulatory process – are largely driven by process rather than outcome. This is not to say that a clearer regulatory process will not support more reliable outcomes, but the nature of the recommendations does not, in my view, enshrine the centrality of peoplein our building design, construction and regulatory systems.

At what cost?

Cost is oft en a contentious issue in construction projects, large or small. Clients will almost always wish to maximise their return on investment. Contractors will always seek to maximise their profi t. Architects, engineers and other consultants will seek to achieve profi t in their fee structure in relation to the time spent on the project. Each of these is a perfectly reasonable aspiration for these businesses.

However, when we introduce concepts such as value engineering, we move cost to a position that overrides other notions of value. In its original derivation (in General Electric during the Second World War), the defi nition of value in value engineering was a ratio between cost and function. You could increase value by reducing cost or increasing function. In modern construction practice, value engineering has become a synonym for cost cutt ing. The ratio is almost never derived through improving function; rather, it is dominated by seeking ways in which to reduce cost. Whether through changes in material, reducing amenity or taking shortcuts, there is litt le context for considering the value of human comfort or experience.

The notion of ethics in the building industry is not new. Every professional body has some concept of ethical behaviour or ethical practice within their code of conduct. However, in many cases, these appear to be designed to avoid placing the professional in a position of legal confl ict or to limit liability. There is oft en a set of confl icting ethical conditions when seeking to address the needs of clients and the needs of users. As an architect, I may fi nd that my client has a set of drivers for reductions in cost and quality of environment that run contrary to the needs of building users. The RIBA Code of Professional Conduct (bit.ly/RIBAcode) speaks much more of my responsibility to the client – in terms of cost and time – than to the user of my design work. Clearly, this does not encourage me to put human life at risk to save the client money, but it does create a context in which the resulting project is driven by factors that may not contribute to a positive and healthy experience for users.

Similarly, The Architects Code: Standard of Professional Conduct and Practice 2017 (bit.ly/ArchCode17), of the Architects Registration Board, is predominated by statements that protect the standing of the profession: manage your business competently, avoid delays, safeguard the clients’ money, have suitable insurance and comply with regulatory requirements. In fact, The Architects Code makes no reference to building users or the public (except that architects should conduct themselves in a manner that does not aff ect “…public confi dence in the profession”).

Ethical pioneers

There are positive examples. Through the Engineering Ethics Vision 2028 (bit.ly/EE2028) the University of Leeds, Royal Academy of Engineering, Engineering Council, Engineers without Borders, and Engineering Professors’ Council have embarked on a ten-year plan to root their industry within an ethical framework. This ambitious plan takes a unique approach, bringing together engineers and ethicists, which looks at creating a profession in which ethics become a part of the “habits, customs and culture” of the industry. Moving beyond regulation and professional conduct, the Engineering Ethics Vision represents a fundamental transformation of the way professional engineers are trained, accredited and able to practise; they are enabled to deal with ethical issues as individuals and a profession.

The Engineering Council, in 2005, developed its Statement of Ethical Principles (bit.ly/ECstethpr). These go some way to placing people in a central position when considering engineering practice and include statements such as: hold paramount the health and safety of others and draw att ention to hazards protect and, where possible, improve, the quality of both the built and natural environments maximise the public good, and minimise both actual and potential adverse eff ects for [current] and succeeding generations take due account of the limited availability of natural resources be aware of the issues that engineering and technology raise for society, and listen to the aspirations and concerns of others.

It is interesting to note that the fi nal statement in these ethical principles is: challenge statements or policies that cause them professional concern.

This suggests that it is incumbent upon individual practitioners to question the ethics of the profession. What is less impactful is the fact that there is a divide between ethical principles and professional conduct. While the Engineering Council

suggests that the principles should be read to challenge those instances where there “in conjunction with the relevant Code are risks. While this does not go so far as to of Conduct or Licence to Practice”, the introduce concepts of quality of experience principles are “neither a Regulation nor a or inhabitation, it is a positive step. Standard”. Thus, one could argue that the Furthermore, CABE’s Code of Statement of Ethical Principles has no teeth. Professional Conduct is backed up by CABE, in its updated Code of Professional “An exercise its Guide to Ethical Professionalism (2020). Conduct (2019), has integrated some ethically in value Like the Statement of Ethical Principles of the based statements that recognise the role of the professional in ensuring engineering at the Engineering Council, on which it is based, CABE is clear to state that the that people are considered. Across the 17 Standards, CABE seeks to frame expense of human statements in the Guide “…are not rules…” and that “…failure to follow conduct in relation to both the profession and comfort is not the guidance is not a disciplinary matt er…” It ethics. Of particular note, is Standard 10: “Seek actively to identify risk; real value – it is not real does, however, indicate that failure to follow the guidance may be report and discuss risk in a responsible manner effi ciency” taken into account in any disciplinary proceedings. and raise concerns with As a result, there is also appropriate persons or organisations a closer coupling between CABE’s Code about danger, risk, malpractice or of Professional Conduct and Guide to wrongdoing that may cause harm to Ethical Professionalism than found in others (known as whistleblowing), or many other institutions support a colleague or any other person to We are moving in the right direction. whom a duty of care is owed and who in good faith raises any such concern.” People vs process

This places an ethical responsibility on I suggest that the problem is one of the individual to be prepared and willing ethicsrather than processes. Improving our regulatory frameworks and processes is necessary, but it will not address the underlying issue. We need to reframe our discussions of the future of our industry to place people at the core of what the industry is about.

We do not build for the sake of building. We build to address human need.

Addressing the human need for good experiences and habitable spaces beyond minimum standards, in addition to health and safety, does not automatically mean that costs must rise. Cost is a human factor, too. But an exercise in value engineering at the expense of human comfort (or, in extremis, human safety) is not real value – it is not real effi ciency.

An approach to construction that defi nes value through a cost-benefi t analysis must not be limited to a simple economic measure of cost-benefi t. Cost and benefi t must also recognise the value of human activity. Crucially, the loss of human life is a cost that no one can aff ord.

An industry that takes an ethical approach to all aspects of its work will not necessarily see costs rise, but it will be less likely to see costs driven down or time savings made at the expense of the people who are the intended users of the outcome.

An industry that integrates an ethical position into its regulatory and professional frameworks will recognise human value and not just asset value.

Returning to a position where people are at the heart of all aspects of our industry will allow us to reposition the discourse of health and safety, economics, technology, education, employment and much more into something positive. The real lesson that must be learned from Grenfell is not about just fi xing a process, but ensuring that the process is about people.

Further reading: Grieves, R. and Jeff ery, K. The representation of space in the brain,

from Behavioural Processes, Vol. 135,

February 2017, Elsevier

Independent Review of Building Regulations and Fire Safety: fi nal report, bit.ly/FireSafefi nal

CABE Code of Professional Conduct cbuilde.com/resource/resmgr/ documents/code_of_professional_ conduct.pdf

CABE Guide to Ethical Professionalism cbuilde.com/resource/resmgr/ documents/guide_to_ethical_ professiona.pdf

Provider of online apprenticeships

Improve retention Increase diversity Attract new employees Utilise levy-funding Level 6 Building Control Surveyor (Degree) Level 6 Chartered Surveyor (Degree) BSc (Hons) and MSc route options Level 6 Construction Site Management (Degree)

ucem.ac.uk/apprenticeships businessdevelopment@ucem.ac.uk T O DEVELOP YOUR TALENT

the journal of the chartered association of building engineers

Would you like to reach over 8,000 CABE members through print advertising?

By advertising within these pages, it will ensure that your brand and proposition is recognised and understood by professionals within the industry.

Contact our sales team today for the latest options

May 2020 the journal of the chartered association of building engineers

June 2020

buildingengineerbudg g the journal of the chartered association of building engineers buildingengineer May 2020 | www.cbuilde.com Enemy within The energy-effi cient buildings with unexpected and fatal consequences Breathing bad Respiratory safety and new carcinogen and mutagen exposure limits The ties that bind Electrical cable ties that maintain integrity in extreme temperatures A new era for fi re safety A history lesson in fi re-safety legislation and why Grenfell is diff erent chartered asso din ent n expecte ed d uences s Breath rea Respira espira new ca ew cn mutag m mut June 2020 | www.cbuilde.com To the Lighthouse Building sustainably with timber raises as many questions as it answers Blue sky thinking From theory to practice, why blue-green roof systems need to become the norm Pooled knowledge The global collaboration that assesses new watermanagement innovations Heating trials Can domestic consumers switch to thinking of heat as simply another utility? J To the Lighthouse Building sustainably with timber raise ber raisesasmany s as many as many y question questions as ions as itans itanswers it answers t answers wers Blue sky thinking Fromtheor From theory om theory y topract to practice, ractice, h why why bluegr blue-green r lue-green r reen roofsyst oofsystems oof systems f systems needto need to beco to beco ecometh metheno me the norm e the norm orm Pooledkno Pooled know oled know know wledg ledge dg Thegloba The global c Thhe global c lobal c ll ollaborat ollaboration oration thatasse thatassesse h that assesse assesse esneww s new waterwatermanagem management i nagement innovati nnovations H Heatingt Heatingtri Heating tri ting trials Can domestic C Candomestic consum consumers umers switchtoth switch to thinking of heat as simply another utility?the journal of the chartered association of building engineers buildingengineer July / August 2020 | www.buildingengineer.org.ukJuly / August 2020

Open and Open and shut case shut case

The ventilation, acoustic and thermal The ventilation, acoustic and thermal comfort problems of our own making comfort problems of our own making

m The rising tide of safety reform Therising tideof safety reform Sea change01 FrontCover _ BE June 2020 _ Building Engineer 1 T e risin ide o a Seach c ghan a e ge

01 FrontCover_ BE May 2020_ Building Engineer.indd 1 Engineer.indd 1 On top of the world Running track above, science lab below, engineering in between

01 FrontCover_ BE JulyAug 2020_ Building Engineer.indd 1 E ineerindd 1 18/05/2020 15:38 The curious case of façadism Saving face

17/04/2020 14:38 17/04/2020 14:38

Placemaking Regenerating brownfi eld sites and re-energising communities Olympian standard Finnish building meets Japanese design to celebrate the Olympics Click and collect The rise of modular and off -site building – can it save the industry?

18/06/2020 11:25 18/06/2020 11:25