4 minute read

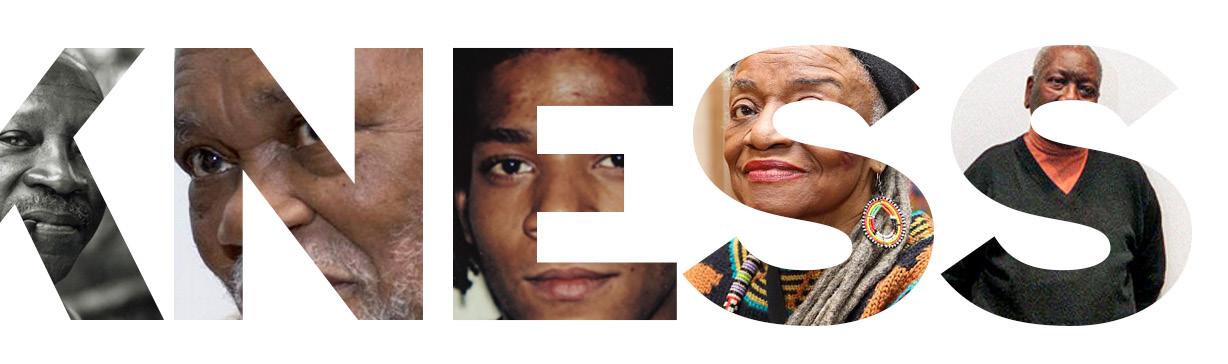

Blackness at MoMA Angelina Rokakis and Elba Rodriguez

at MoMA

Advertisement

Using Among Others: Blackness at MoMA as a guide, I found quite a few artists that really inspired me. It’s important during not only this month but every month to educate oneself on the unfamiliar. Here’s a start, I implore you to not stop here but to continue to explore and learn about all the wonderful Black Artists we have in our collection. Listen to Ann Temkin, Darby English and Howardena Pindell discuss the history of blackness at MoMA.

by: Angelina Rokakis and Elba Rodriguez

Photography

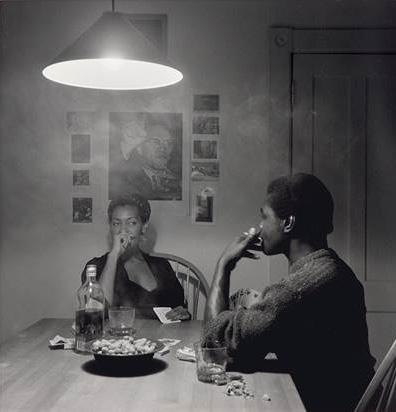

Carrie Mae Weems

Untitled (Man Smoking) 1990 A part of her Kitchen Table Series, Weems invites you into her home to observe a study of the battle of the sexes and domesticity. She allows for an honest look into the challenges and rewards of womanhood.

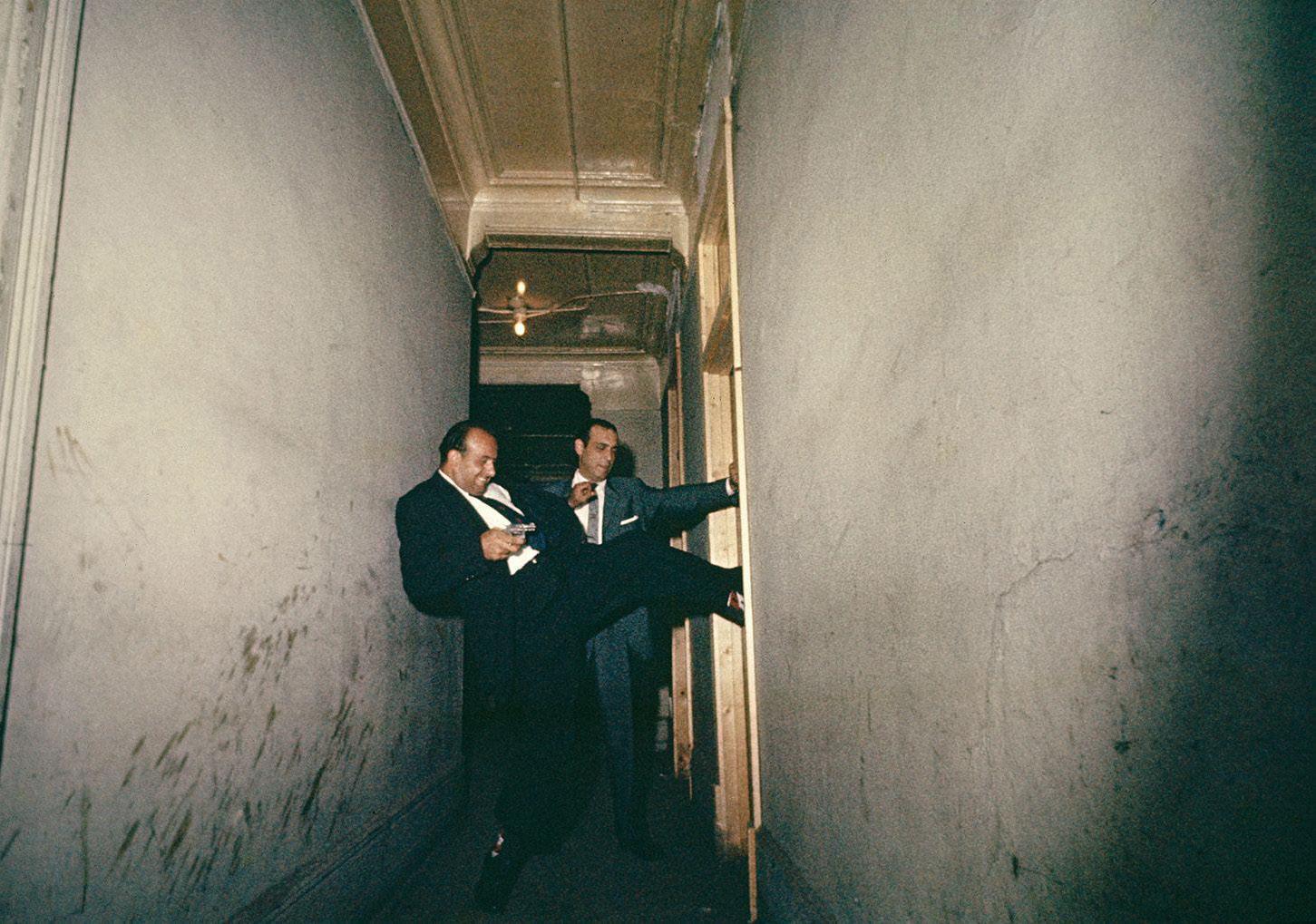

Gordon Parks

Raiding Detectives, Chicago, Illinois 1957 Park’s photographs are not just pictures, but harrowing moments of his everyday life caught on film. “I chose my camera as a weapon against all the things I dislike about America—poverty, racism, discrimination.” Over sixty years later, the struggles remain.

Ousmane Sembene

Xala 1975

Xala, Sembène’s film about a modern, corrupt, and prosperous businessman stymied by what he believes to be a curse, is in both French and Wolof, one of Senegal’s principal languages. The word xala means “curse” in Wolof, and the curse visited upon the protagonist (Thierno Leye), a respected member of the Chamber of Commerce in Dakar, is one of sexual impotency.

Pope L.

Thunderbird Immolation a.k.a. Meditation Square Piece 1978 The artist is seen meditating in a half-lotus pose on the sidewalk outside a prestigious commercial gallery building in New York’s SoHo neighborhood while sitting atop a yellow meditation square. Wearing a black suit, white dress shirt, and bow tie, he pulls out of a brown paper bag two bottles of Thunderbird wine, a bottle of Wild Irish Rose, a can of Coca-Cola, a plastic measuring cup, and wooden matches that he arranges in a ring around himself, occasionally spelling out words with them. He then periodically pours the wine (a cheap fortified alcohol marketed to inner-city neighborhoods) over his body. By dousing himself in flammable liquid, surrounded by matches, Pope L. references the legacy of fire rituals and meditative practices associated with various eastern religions and acts of resistance.

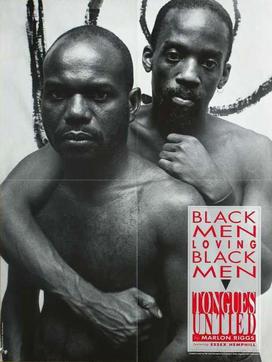

Marlon Riggs

Tongue Untied 1989 Feeling doubly ostracized by society and a white-centered gay community, Riggs uses his experimental documentary, Tongues Untied, to legitimize, not only the presence of black queerness, but of blackness in America altogether.

Painting/ Mixed Media

Chris Ofili

The Holy Virgin Mary 1996

Depicted on a lush, glittering ground of shimmering orange resin that recalls the gold leaf of religious icons, Ofili’s Virgin Mary is resplendent, majestic, and imperious yet also suffused with sexual potency. Close inspection reveals the delicate, fluttering cherubim surrounding her to be crafted from images of women’s buttocks clipped from pornographic magazines. The introduction of eroticism to the Christian Virgin’s sacred image is far from new. “When I go to the National Gallery and see paintings of the Virgin Mary, I see how sexually charged they are. Mine is simply a hip-hop version,” Ofili has said.

Betye Saar

Black Girl’s Window 1969

Before Black Girl Magic, there was Black Girl’s Window. Embellished with astrological-looking images, the window is a reminder that a dual perspective exists and that little black girls see you, just as well as you can see them; a concept Saar seals with a winking eye dependent on the viewer’s interaction.

Sculpture

David Hammons

Untitled (Night Train) 1989

“Outrageously magical things happen when you mess around with a symbol,” Hammons has remarked. The artist constructed Untitled (Night Train) using found objects from the streets of New York—bottles of Night Train and Thunderbird, inexpensive brands of alcohol. The ring of bottles is embedded in a pile of coal which, together with the work’s title, evokes Black culture and lore from the underground railroad to the Freedom Train. The work’s components also combine to create visual puns: the coal and Night Train bottles form the name Coltrane, while the Thunderbird bottles allude to another great jazz saxophonist, Charlie “Bird” Parker.

Senga Nengudi

R.S.V.P. I 1997/2003 Nengudi’s R.S.V.P. I is a sculptural environment composed entirely of two ordinary materials: pantyhose and sand. The pantyhose—ten worn pairs—are tacked onto and stretched between two walls in the corner of a room: the taut nylon mesh evokes spidery limbs, while the center gusset, filled with sand, is twisted and knotted into bulging sacks that sag toward the ground. R.S.V.P. I highlights the formal concerns of abstract sculpture, such as weight, tension, and spatial relations, yet is undeniably redolent of fleshy associations, particularly those of the female body. Referring to her works as “abstracted reflections of used bodies,” Nengudi created R.S.V.P. I in part as a response to the changes her body had undergone during pregnancy and as a rumination on the more gradual physical transformations that come with age