6 minute read

“FORWOOD”

from PNGAF MAGAZINE ISSUE #9D3 of 12th Dec 2021. Rehabilitation PNG's Degraded Tropical Moist Rainforest

by rbmccarthy

“FORWOOD”

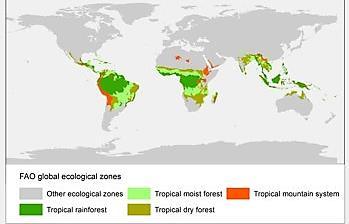

Globally FAO estimated that there are some two billion hectares of degraded tropical forests in the world. Often, these are remnant forests, left over from harvesting of wood and nonwood forest products. The soils in these areas are usually susceptible to erosion and have low fertility. These forest areas are often susceptible to forest fires.

Advertisement

Tropical forest ecological zones (FAO)

However, some species of trees thrive in these degraded ecosystems and often, due to the poor soils, such sites have few alternative uses (other than to be used as forests). The role of foresters in a cost-effective way, is to apply the use of natural regeneration techniques/agro forestry/conservation techniques as currently known and yet to be developed, across some two billion hectares of degraded tropical forest lands in the tropics. In tropical forest where the harvesting operation is based on a selection system with only merchantable stems above a certain diameter being removed, the theory being that the smaller stems will grow over a nominal 35-year period.

Concerns re the selection system of management include:

• That without proper monitoring, harvesting operators may remove smaller species. • That even if smaller stems are not removed, poor harvesting techniques can damage the remaining smaller stems and they may not recover from that damage. • Excessive logging may so change the character of the forest, that the resultant smaller stems may not survive. • In areas of high population density, the proliferation of unsustainable practices is a major problem. Logging in accessible areas of these moist tropical forests is intense and deforestation and forest degradation prevails.

• The pressure to convert forestland to farmland to meet expanding agricultural requirements is often intense. • Setting aside forests for protection or for sustained production of wood in areas of high population density is difficult because of the generally high opportunity costs and political costs of such actions.

Much of the early work in PNG during the 1950’s and 1960’s on the development of silvicultural systems involving natural regeneration techniques, was based on a composite of Malayan systems interlinked with North Queensland moist rainforest silvicultural systems. At the same time, these activities together, had to interlink with the impacts of the historical processes of shifting cultivation, fallowing, selective forest tree harvesting and the impact of the introduction of steel axes.

Renewed effort in the 1990’s resulted in Vigus’s9 development of the technique of Reforestation Naturally. This technique developed by Vigus meant looking after the natural regeneration that occurs after logging through tending. If, at the first tending there were gaps, enrichment planting was undertaken with transplanted seedlings from nurseries or elsewhere from within the forest area. This process was developed such that land ownership resides with the people rather than governments.

The North Queensland experience demonstrated that moist tropical rainforest can be sustainably managed for wood production, provided adequate attention is given to tree marking as a silvicultural tool. Cameron and Vigus 1994 review10 identified issues as:

• Effect of shade on regeneration in relation to silviculture. • Effect of controlled logging practices and silviculture implications for sustainable forest management.

All authors referred to in this magazine, emphasized that timber stand improvement techniques follow the Baur’s11 decree of the maintenance of ecological processes. This is to limit the impact of timber harvesting on the tropical forest and at the same time ensure maintenance of biodiversity and optimising community benefits.

The PNG Logging Code of Practice 1996 was introduced to ensure reduced impact of logging operations on the residual stands of the rainforest and protection of watersheds.

Richards12 1997, in comparing the Queensland rainforest silvicultural practices for selection rainforest logging compared to the present rainforest logging system in PNG, posed the following issues to be addressed, once a detailed review of the current system in PNG was undertaken:

• Should the minimum cutting diameter be the same for all species?

9 Vigus T 1998 Paper “Planim diwai – a discussion on the social, economic and conservation issues of monoculture forestry plantations and reforestation naturally.” AFPNG Lae Conference 1998.

10 Cameron A L & Vigus T 1993. Papua New Guinea Volume and Growth Study: Regeneration and Growth of the

Tropical Moist Rainforest in Papua New Guinea and the Implications for Future Harvest. Brisbane CSIRO Division of Wildlife and Ecology (for the World Bank). 11 Baur G 1962 The Ecological Basis of Rainforest Management Andre Mayer Fellow 1961-62 UN FAO 499p. 12 Richards B 1997 The Silvicultural Imperative in Forest Management First Forester’s Refresher School June 1997 Lae PNG. PNG Forestry HRD Project AusAid.

• Should tree marking rules be formulated and written into the PNG LCOP? • Should rules for the identification and marking of residuals be included in the PNG

LCOP? • Should there be a requirement for the retention of seed trees? • What is the minimum economic cut for the various forest types? • Would it be economically efficient to work on a shorter cutting cycle to service a downstream processing industry? • What research is needed to provide the data and information required for sustainable timber management of PNG’s moist tropical rainforests?

Globally, a common feature of discontinued natural forest management programmes in tropical moist forests is that technical feasibility is never cited as the reason for the discontinuation. Often political developments have meant that institutions dealing with forest management have been given new directions, and new techniques, promising more rapid results than those achieved through the relatively slow growth of natural forests.

These are not problems of species diversity, lack of understanding of ecosystem dynamics, inability to retain adequate regeneration or lack of response to silvicultural treatment. The problems concern land-use policy, socio-economic conditions, and political realities.

A large part of the problem is that the productive potential of abundant resources is undervalued. The problem is to expand the time horizons of policy makers. The tropical world already offers many examples of the consequences of continuing to neglect sustainable resource management policies. Once productive capacity has been reduced, efforts to restore it become very expensive.

Although more information would be useful in areas such as growth and yield statistics, annual increment, and sustainable removals, there is now enough information to implement a sustainable natural system of management. Any claim that the silvicultural and yield regulatory elements are the limiting factors to the advancement of forest management is hard to sustain.

National forest policy must ensure that population development is in harmony with the optimum productive capacity of land available. Institutions responsible for management must have long-term programme stability, with stable leadership in key positions to provide continuity. Effective training institutions must prepare workers from the technician to the doctoral research level, and institutional mechanisms must place knowledgeable and competent personnel in the field where management activities occur.

Profitable management must be integrated with the national economy and the world timber market. Those plans must assess the demand for products 20 years or more in the future. Effective legislation and national land-use planning that identify the forested areas to be managed are indispensable.

It would be foolish to maintain that the current management picture in moist tropical forests is an encouraging one. In the three great centres - the Amazon Basin, Central Africa, and the islands of Southeast Asia - substantial areas of forest are being cut over or converted to other uses. Significant programmes of silvicultural treatment are occurring only in Malaysia.

Achieving sound management will not be easy, but failure will result in the loss of the great majority of tropical rain forests. There is every indication that economically unproductive areas in tropical countries will continue to be highly vulnerable to development or conversion, even if such development is unsustainable. There is no economically profitable alternative use for large areas of biologically highly productive tropical forests.