8 minute read

Mining Stone

Most people know that the steel in American cities’ modern and historic skyscrapers, bridges, and industrial structures is partly composed of iron mined in our neck of the woods. Far fewer people are aware that stone mined here is part of dramatically designed interiors of those same skyscrapers, striking architecture in city parks and public spaces, and touching memorials including the 9/11 Memorial in New York City and the 35W Bridge Collapse Memorial in Minneapolis.

Two Minnesota-based companies work the quarries near Ely–Coldspring

Advertisement

Stone in Cold Spring and Kasota Stone in Mankato. There are three Coldspring quarries in the area and one Kasota Stone, each employing four to ten people at their quarries. These are highly skilled workers who specialize in one of the machines used to assess, cut, drill, and shape the stone, but each person is capable of running some of the other equipment and doing the general maintenance required to pump rainwater out of the pit, ensure the machinery is running smoothly, and maintain a safe work environment. These employees are well paid with good benefits and never get laid off because the demand for stone is high and fluctuates very little.

Semis with 75-foot long trailers are sometimes seen in Ely or Babbitt and along Highways 1 and 2 on the way to the North Shore. They carry a block of stone that may appear rather small and insignificant on such a big platform, set in the middle of the trailer bed. It may look unassuming, but this chunk weighs up to 52,000 pounds and can be shaped into a dozen or more headstones for graves, countertops for many kitchens, a long wall for a mausoleum, or a walkway in a public park.

Winter Survival Repair

At Joe’s Marine & Small Engine Repair Chainsaws, snowblowers, generators.

Mechanics are on duty and parts are in stock. 25 W. Chapman St., 219-365-6264

Loads over 52,000 pounds require special permits and specialized equipment. You may occasionally see one of these accompanied by oversize load warnings. Be sure you stay in your lane on these roads. Such a load makes stopping fast or swerving very difficult.

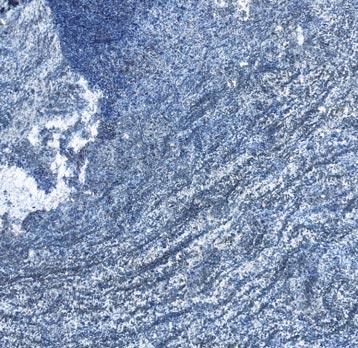

At the quarry on the New Tomahawk Road between Highway 1 and Babbitt, Coldspring mines gabbro that is sold as Mesabi Black granite. This is a full time operation that provides stone for many projects at once. Lake Superior Green, a similar stone but with a greener tint due more of the mineral olivine, is quarried at Coldspring’s operation on the Wanless Road in Isabella. This is done only for special orders, moving the equipment from the Tomahawk operation to produce what is needed. On Echo Lake, near the north end of the Echo Trail, is a third Coldspring quarry that produces a pinker stone, mined mostly for specific customer orders. Kasota’s local quarry is off the South Kawishiwi Road. Their quarried and processed stone is sold as Superior Northern Granite.

The Kasota quarry is working in a rare formation with unusually few vertical seams. Such seams, which can be thousands of feet deep, determine the maximum size of a quarried piece since the rock fractures along them. The lack of seams allows Kasota to quarry blocks up to 20 feet long, limited only by the ability to transport it.

Both companies have been in business for well over 100 years, but their Ely area operations are closer to 30 years old. Both are headquartered in Minnesota, but have quarries in many different locations throughout the U.S. They pride themselves on the quality and sustainability of both their operations and their products.

Stone is a very “green” substance and can last for centuries, unlike concrete. The mining process uses only water on the land, although of course plenty of fuel is needed to operate the machinery and transport the blocks. There is no slag or contaminated run-off. When operations cease, any leftover rock or dirt is put back in the hole created by extracting the blocks. It is likely that it will fill with water and become a small lake. The areas around the pits that are impacted from industrial use will be reforested.

State geologists have done extensive mapping to find suitable quarry sites. These are leased to stone processing companies on a bid basis. The companies pay royalties to the DNR and U.S. Forest Service. That money supports schools if it is from state land. Federal land payments go to the National Treasury with a portion retained locally to cover administrative expenses.

The desirable stone is igneous rock that was a more recent (geologically speaking) intrusion into the surrounding metamorphic rock that was created by material deposited in ancient shallow seas a billion years ago and hardened by millions of years of pressure, heat, and the movement of Earth’s crust. These volcanic intrusions below the surface cooled slowly allowing the crystals to grow, then surface glacial erosion exposed these areas and enabled geologists to identify them for extraction.

Today’s quarrying methods using saws and drills are safer and produce less waste rock than older methods that used explosives and less precise machinery. First a cut is made at an angle that will work to develop a road as the quarry reaches deeper into the rock. A modern piece of equipment can drill the width and depth of a block in two hours. This same procedure done by jack hammers used to take two men 80 hours. The wire saw makes the final smooth cuts, and a special hydraulic spreader tips the block out of its position so it can be hauled out of the way. Each block is inspected for cracks, fissures, and other imperfections that could create instability in a finished piece. If it is approved, the block moves on to be assessed for its best use. Can it be cut in the thick slabs needed for paving stones, or will it be better suited to grave markers or counter tops? Does it have a crystal structure that gives it a more textured appearance, or is it smooth? Clients have different tastes, and some applications, such as a wall that will be engraved, require a more consistent coloration. Once it is classified and marked, the stone is set aside to await the right customer or immediately transported to fill the needs of a project already underway. Four trucks a day, four days a week, haul the Coldspring blocks to the fabrication operation at the main headquarters. There the blocks are prepared for the customer–cut to size, smoothed and polished. From Cold Spring the finished stone is hauled to the site where it will be installed, and the customer takes control of its final form and placement. There are also businesses that purchase the raw stone to use for their own residential or commercial operations, creating counter tops, stairways, mausoleums or columbariums, or walkways, pools, and benches at parks.

Hauling the huge stone pieces requires skilled drivers, especially on the curvy parts of Highway 1. One driver died a few years ago when his trailer tipped over on a curve by Stony Lake. Last summer, a driver with a load on came to a moose in the middle of the narrow dirt road near the Kawishiwi Summer Homes Road. “I’d never seen a moose before,” he exclaimed. “I was eyeto-eye with it!!” This may have been a bit of an exaggeration as his seat in the cab was a good eight feet above the ground–or it was a very big moose. The moose wasn’t interested in getting out of the way. Luckily, the driver’s skills matched the situation, and he was able to steer off the side of the road without tipping over the trailer or hitting the moose. He spent the rest of the morning in Zup’s parking lot waiting for parts to repair the damage under the trailer from a boulder he couldn’t quite clear.

What happens to pieces of stone that are not the right shape or have too many cracks to be useful in an architectural setting? Set aside as “waste rock,” they are not really wasted. Homeowners in the area may have these chunks trucked to their property for landscaping use. Some are ordered for such projects as the Lake Walk in Duluth for fill and borders. Occasionally a crusher is brought in to grind the stones into gravel for roads.

These modern quarries are not the only commercial enterprises in Ely’s history of rock extraction. The earliest evidence of quarrying has been found on Knife Lake and was likely left there shortly after the glaciers receded, as much as 8,000 years ago. (See Ely Summer Times 2016 for an article about pre-historic quarrying and trading.)

Quarrying in the Arrowhead was also carried out in the 1890s, possibly related to development in Chicago following the devastating fire in 1871 and preparation for the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. Evidence of 20th-century activity can be found at two sites close to Highway 1. Heart Lake Quarry (also called Rose Quarry) is a short hike along Forest Service 1468 road near milepost 301. Rock there was mined in the 1930s and sold as “Arrowhead Black Granite” probably sending stone to the skyscrapers being erected in Chicago and Cleveland. In more recent years the quarry pit has served as a rock climbing site for adventure-based camps like Outward Bound.

The other old quarry, not named and for which no history could be found, can be seen by hiking along a slightly obscure trail that takes off to the west from a stop sign near milepost 299. At the unnamed quarry a foundation can be seen. Some Ely visitors with knowledge of stone cutting history in the U.S. estimate that it was worked in the 1950s. Trees now growing up inside the foundation can also help provide dating, although it may be hard to estimate when the building deteriorated to the point that soil and rain could provide a suitable environment.

The methods of cutting and removing stone blocks changed from decade to decade. Originally the rock was drilled by hand. Then drills and jack hammers were powered by compressed air and later by hydraulic systems, with explosives being used at times. Examining the quarry walls and waste blocks can reveal the methods used and help with establishing operation dates.

At both these sites, the edges of pits are littered with blocks of waste rock. If you explore these old sites, be sure to keep kids and pets close by to avoid accidents at the sudden steep drops into abandoned pits. Both locations have good blueberry picking and contain a variety of lichens and mosses to study along the pit edges and on old blocks.

For many years, the Rock Crusher was a landmark on the north side of highway 169 three miles west of town.

Now it has eroded into a much smaller hill and trees have grown up around it so that it is barely visible from the road. It is private property and trespassing is forbidden. David Kess wrote about it in an article for Ely-Winton Historical Society The rock crusher came about because of the Greenstone rock that could be crushed to provide a mineral surfaced roofing. [It was in operation] from 19211932. When in full production ten cars [a day] were sent out. At its peak 45 men were employed, with 2 supervisors, and 1 manager. The workers were paid $.35 per hour and worked 10-hour days. Young people made many "unauthorized" bike trips there to climb the mountain, explore, and swim. Some even went cliff jumping and skinny dipping into the emerald green water of the abandoned quarry on the other side. A secret getaway.

If you’re interested in a tour of both the old and new quarries, check the Ely Field Naturalists website for next summer’s weekly field trips. At least one tour will be offered next summer.

Both quarries offers tours for architects and other potential clients. They occasionally can accomodate the public in a small group tour. These must be scheduled months ahead of time. For more information use the contact form at the websites ColdspringUSA.com and Kasotasf.com