6 minute read

Skiing Trials

Ski Trials

by Becca Brin Manlove

Last winter, stutter skiing my way across the wide lake in full sight of new neighbors, I felt self-conscious. On this large frozen lake my indecision about where to go and my self-taught skiing technique were on stage. On shore was a long row of cabins, big and small, a surprising number of them winterized and occupied. These new neighbors’ views were all pointed at the lake. The islands I hoped to tuck behind were still a distance away. Maybe too far away given the short light of this December day and my meandering route.

I was skiing on snowmobile tracks, following their wide loops and S curves. Bumping from one track to another when the new one promised to head where I wanted to go. Silly really. Could have skied a beeline to the islands in less time. But I was scared. Scared of this new lake, which was fed by springs, and of December ice—not yet thickened by months of deep freeze days. I didn’t know where the weak ice might be. That’s why I clung to the tracks. If a snowmobile hadn’t dropped through, then hopefully the ice wasn’t too thin to support my weight on skis. Scared of getting lost— which I knew was not real. All I had to do was turn around and follow the wavering thin lines my skis had made back to my starting point. The winds were calm; snow wouldn’t cover my trail. The sky was clear. I could see the sun still in the sky and with the bright white of snow, darkness wouldn’t just jump down on me.

Other worries, not about skiing, rose like a swarm of black flies into my mind. I stopped. So much else to do, what was I doing out here? I lifted one ski to turn it around, standing in plié, started to lift the other ski, and of course I fell over. Luckily, I fell over. Because sitting there in that humbled position, I heard Mike laughing. His laugh was big and loud. Impossible not to laugh, too.

“City Lag, Beck. You’ve got it.” Mike’s been gone fourteen years, but I still hear him sometimes. The pandemic was almost a year along. I hadn’t been near a city for ten months. But I knew Mike was right. He gave silly but apt names to things and situations. Crazy Chain for Lakes One through Four. Walking Zone for the routes with long portages like Angleworm and . He was the Camp du Nord winter caretaker for three seasons before I married and joined him. When my first summer season ended and our fall season of mostly weekend guests began, I learned about City Lag.

Mike remembered names and stories of the returning guests. He was irreverently funny and beloved. People yelled his name with delight when he knocked on their cabin door to welcome them. So I was surprised when he turned down invitations to linger in the cabin, talking to one or another of the guests while the rest of the group scurried in and out, claiming beds and unpacking. They offered beer, cookies, even supper. Most of the time, Mike graciously deflected the invitation, saying we had other cabins to welcome.

We made a second round of cabin visits the next morning to be sure the guests were comfortable and to give out maps of the ski/hiking trails. New trails were being built each fall and spring, so maps were helpful even for visitors who had skied them before. I asked why we didn’t just combine the visits and give them the trail maps when we welcomed them.

“Nope. Most of these folks have City Lag when they get here. Trying to give them too much information at first can be dangerous.”

“City Lag? Like Jet Lag?”

“Yes. They’re still on city time, all speeded up. Pumped full of adrenalin. Worried about what others think about them. They won’t hear anything we say except where the outhouse is. And maybe not even that. They’ll be much

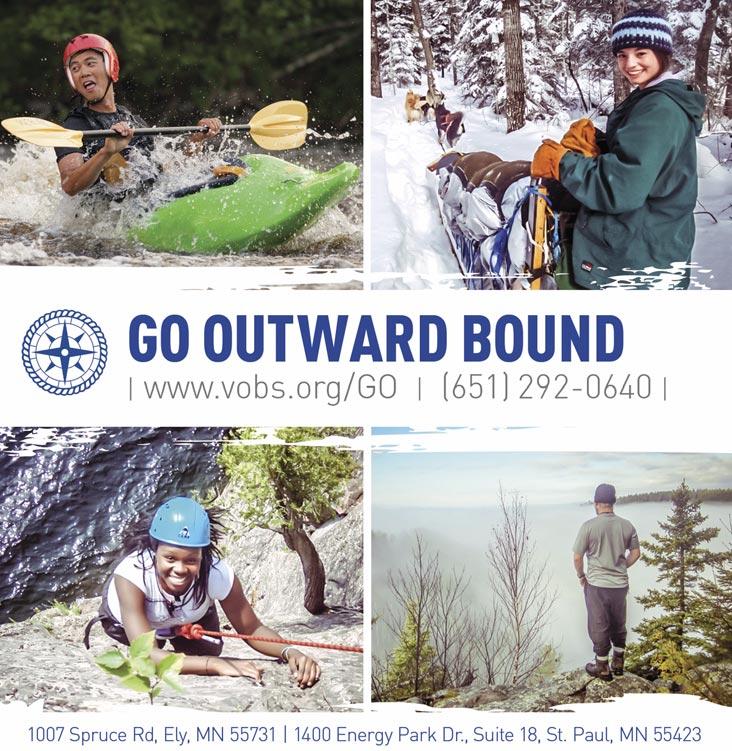

Snowmobile tracks provide a firm surface often taken advantage of by skiers, sled dogs, deer and other wildlife. But users still need to check ice. A snowmobile going fast can easily cross bad ice and even open water.

easier to talk to in the morning. Here’s a rule. Don’t give them the map of trails until the next morning, when they’ve slowed down and everyone is listening.” But one year on the Winter Solstice a large group arrived just after lunch. The leader was an old friend of Mike’s and very familiar with the camp. He asked for a few copies of the trail map so that they could get out for a quick ski. I gave him some and pointed out the newest section of trail. There was almost a foot of fresh snowfall. Only he and one other guy listened. The rest were busy unpacking. It was pitch black when Mike’s friend pounded on our cabin door, yelling for help. His wife, their ten-year-old daughter, and a friend were missing. Most of the group had slowed down to accommodate a few younger skiers, but the missing three moved faster and lost touch with the group. As daylight faltered, the man turned the rest of the group around and they made it back but with difficulty. As darkness fell, their tracks were harder to find.

While we threw on layers of clothes and ski boots, he told us where he thought they were. The fresh snow that was probably hindering them would help us find them. Mike stuffed blankets, water bottles, matches, flashlights, and first aid supplies into a pack. He directed two of the strongest skiers from the group to change into dry clothes and collect a pulk and winter camping

supplies from a nearby neighbor. He would tie trail tape along our route for them to follow.

We were almost to the trailhead when our headlights shone on three people stumbling down the road, skis over their shoulders. They were exhausted, grateful for the ride, and embarrassed for having caused such worry. The daughter had the most energy, so she explained. They thought they were on a loop and kept going forward even as the sun slipped below the tree line. Luckily, the trail they followed was blocked by a fallen tree and snow laden branches. They turned around and stumbled back along their own tracks. The next morning, Mike and a few other members of the group followed the tracks. The three were on a one-way trail that wound for miles into the wilderness.

That was an extreme situation, even for City Lag. But I learned a lesson—to encourage people to settle into a new situation before dashing off toward some other goal. Unfortunately, it’s one I also need to learn and re-learn. Both in advising other people and in talking to myself. I will miss the beauty, the light, the love right in front of me if my mind is full of chaotic thoughts over borrowed trouble. Allowing fear (either physical or social) to cloud my goals or limit my actions.

I stood up and dusted snow off my butt. Left my City Lag in the hollow made by my backside. Scooted across some fresh snow to pick up another snowmobile trail that ran in a wide loop in front of the island. No tracks between the islands yet (where ice may well be weak), so I followed this track as it cut back west toward brilliant clouds above a sinking sun. Light would linger long enough for me to identify my little cabin nestled into the hillside. And, if not, light would shine from one of the other cabins. Then I’d meet a new neighbor by admitting I was lost and asking for directions.