9 minute read

Future Focus

from Inside News September 2023

by RANZCR

Dr Pey Ling Shum is a first-year radiology registrar at Austin Hospital, who has published articles on the subject of environmental sustainability in radiology. Here, she outlines the results from an environmental waste audit at Austin Hospital and explores the ways radiology departments could reduce their waste generation.

Healthcare contributes enormously to the world’s carbon footprint: 7,000 tonnes of solid waste can be generated by one hospital alone in a day (1). In its 2022 Annual Report, Victoria’s Austin Health (comprising Austin Hospital, Heidelberg Repatriation Hospital and Royal Talbot Rehabilitation Centre) reported that each patient produced, on average, 8.92 kg of total waste per occupied bed day (2). Meanwhile, one Interventional Radiology (IR) department studied in New York emitted ~23,500 kg CO2 emissions over five consecutive weekdays (3).

This is equivalent to burning 9,900 L of gasoline and an average of 243 kg CO2 generated per IR procedure (3). Climate change is already happening and the situation is quite worrying. Australia’s average temperature has increased on average by 1.44 ± 0.24 °C since national records began in 1910 (4). In addition, climate forecasts show that extreme weather events such as heat waves, drought, hailstorms and flooding are getting more frequent and severe. We are already seeing the negative impacts of climate change and global warming. The ‘Black Summer’ bushfire season in 2019–2020, the 2022 flash flooding in New South Wales, 2023 flooding in Auckland, and coral bleaching throughout the Great Barrier Reef are just some examples of recent local events.

There are both direct and indirect health consequences of climate change—from morbidity and mortality directly resulting from natural disasters to the indirect consequences of mental illness, air pollution, vector-borne disease and impaired access to clean water. For example, rising global temperatures will increase the climate suitability of mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue, increasing the length of the transmission season and expanding the population at risk who might be immunologically naïve and unprepared (5).

AUDITING AT AUSTIN HOSPITAL

Recognising the importance of environmental sustainability and the impacts of climate change, we evaluated our practice at Austin Hospital and performed an audit to measure the amount of waste that was generated in each neurointerventional radiology procedure. Seventeen neurointerventional procedures were audited, including digital subtraction angiograms, endovascular clot retrieval, coiling and embolisation cases. We found that an average of 8 kg of waste was generated per case with coiling procedure producing the greatest waste burden of 13.1 kg (6). The majority of waste was clinical waste, which constituted about 63 per cent, followed by general waste, accounting for 20 per cent (6).

When this is compared to international benchmarks, the amount of clinical waste was significantly higher, because clinical waste should not be more than 15 per cent of total waste (7). This excess of clinical waste has significant impact on the environment because it requires treatment prior to safe disposal, unlike general waste which goes straight to landfill. Most clinical waste is incinerated, releasing toxic fumes and heavy metals into the environment—incineration of 1 kg of clinical waste produces approximately 3 kg of carbon dioxide (8).

Therefore, appropriate waste segregation is one of the most important sustainability initiatives. Waste can be classified into general, clinical, cytotoxic, radioactive, recyclable, pharmaceutical and sharps. Brassil et al. found that waste is 60 per cent more likely to be inappropriately segregated when the risk bin was physically closer to the interventionalist than the non-risk bin during procedures (9).

Misclassification of waste has a financial impact, too, resulting in an increased cost of up to 20 times to treat and dispose of waste appropriately. The cost of general waste disposal in 2019 was AU $0.15/kg compared to AU $0.95/kg for clinical waste (6). On the other hand, it is free to dispose of cardboard, paper, PVC and soft plastic if the items are segregated individually.

Staff education is crucial to prevent misclassification of waste, and bins should be labelled with clear signage and examples. Ongoing staff education could be achieved by incorporating waste-training requirements into existing compulsory health and safety training, as well as using posters and signs to increase awareness. Forming hospital ‘green teams’ can also increase staff awareness and bring knowledge into practice.

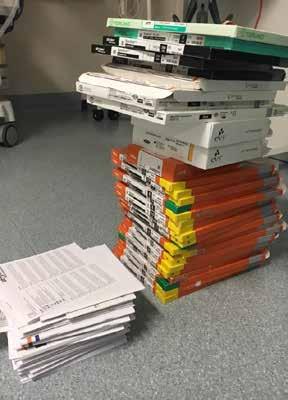

Another significant finding from our waste audit is that a substantial amount of packaging and user manuals were generated. One coiling with tumour embolisation procedure produced 2.7 kg of packaging boxes and 2.6 kg of user manuals (6). These paper instructions are thick and none of them are read prior to procedure. We suggested that paper instructions can be substituted with online manuals via web pages or Quick Response (QR) codes.

One coiling with tumour embolisation procedure produced 2.7 kg of packaging boxes and 2.6 kg of user manuals.

OTHER WAYS TO REDUCE WASTE

In day-to-day radiology department general practice, there are many ways to reduce paper waste such as the use of digital notepads, double-sided printing, the use of recycled paper and envelopes, reduced printing of request forms and provision of scrap paper for internal notes.

At Austin Hospital, there has been a move to single-stream recycling (where all materials are collected in one location). There are also small, specialised recycling streams such as single-use metals, excess or expired stock, electronic waste and soft plastics. We should choose to purchase products from manufacturers who have strict green policies and are committed to recycling and reusing their products, if not disposing of their expired equipment in an environmentally friendly way. Recently, Stryker has launched a pilot program in Victoria to collect and recycle all its InZone coil detachment devices at zero cost to the hospital. The printed circuit board, which includes 213 microchips and two AAAA batteries, is repurposed, while the five plastic mouldings and six screws are recycled.

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) accounts for 25 per cent of single-use waste in hospitals. The PVC Recycling in Hospitals Program collects three specific medical products (IV bags, face masks and oxygen tubing) for recycling into useful new products such as hoses for fire extinguishers and play mats for children.

Opened but unused items are another significant source of waste, which can be prevented by opening devices only when necessary, using operator preference cards, educating staff and having better communication between operators and support staff. Unused equipment can be donated or repurposed. Moreover, interventional radiologists can engage with suppliers to redesign procedure packs according to local preferences to minimise unnecessary items and packaging. Procedural packs should be reformulated so that items that are not used regularly are removed and packaged individually for occasional use. Electricity and water use are other key considerations when evaluating overall environmental impact.

Electrical usage in radiology departments is immense considering the need to power CT, MRI, ultrasound, fluoroscopy and PACS monitors. We encourage radiologists to shut down their PACS stations after work and set monitors to go into sleep mode if not in use for more than 20 minutes – a simple action that can save an immense amount of electricity consumption. Prasanna et al. found that 83,866.6 kWh of electric consumption and USD $9,225.33 annually can be saved by just shutting down workstations and monitors after an eight-hour workday (10).

We encourage radiologists to shut down their PACS stations after work and set monitors to go into sleep mode if not in use – a simple action that can save an immense amount of electricity consumption.

Alcohol-based hand rubs are one way to reduce water (and drying towel) waste. In fact, swapping from scrub soap to alcohol-based waterless scrub solutions could save up to 2.7 million litres of water in a year (11). A UK study showed that a standard three-minute surgical hand wash for one staff member used up to 18.5 L of water compared to an average volume of 15 ml of alcohol rub (12). Moreover, alcohol-based hand rubs are less likely to cause hand dermatitis compared to surgical scrubbing.

In a nutshell, we should reflect on our day-to-day practice and advocate for changes to reduce waste and achieve environmental sustainability in radiology departments. We encourage everyone to discuss this issue within their department to increase staff awareness. Every small step counts towards protecting the environment for future generations.

1. Weiss A, Hollandsworth HM, Alseidi A, Scovel L, French C, Derrick EL, Klaristenfeld D. Environmentalism in surgical practice. Current problems in surgery. 2016 Apr 1;53(4):165-205.

2. Annual Report 2021-22 [Internet]. Austin Health; [cited 2023 Jul 9]. Available from: https://www.austin.org.au/Assets/Files/Austin%20Health%20 Annual%20Report%202021-2022_Online%20version%20(1).pdf

3. Chua AL, Amin R, Zhang J, Thiel CL, Gross JS. The environmental impact of interventional radiology: an evaluation of greenhouse gas emissions from an academic interventional radiology practice. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology. 2021 Jun 1;32(6):907-15.

4. Australian climate change observations [Internet]. AdaptNSW; [cited 2023 Jul 9]. Available from: https://www.climatechange.environment.nsw.gov. au/australian-climate-change-observations#:~:text=Australia’s%20climate%20has%20warmed%20since,night%2Dtime%20temperatures%20 have%20increased.

5. Colón-González FJ, Sewe MO, Tompkins AM, Sjödin H, Casallas A, Rocklöv J, Caminade C, Lowe R. Projecting the risk of mosquito-borne diseases in a warmer and more populated world: a multi-model, multi-scenario intercomparison modelling study. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2021 Jul 1;5(7):e404-14.

6. Shum PL, Kok HK, Maingard J, Schembri M, Bañez RM, Van Damme V, Barras C, Slater LA, Chong W, Chandra RV, Jhamb A. Environmental sustainability in neurointerventional procedures: a waste audit. Journal of neurointerventional surgery. 2020 Nov 1;12(11):1053-7.

7. Wyssusek KH, Keys MT, van Zundert AA. Operating room greening initiatives–the old, the new, and the way forward: a narrative review. Waste Manag Res. 2019 Jan;37(1):3-19.

8. McGain F, Jarosz KM, Nguyen MN, et al. Auditing operating room recycling: a management case report. A & A Case Reports 2015 Aug 1;5(3):47-50.

9. Brassil MP, Torreggiani W, Govender P. Recycling in interventional radiology—steps to a greener department. Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe (CIRSE) 2019, Barcelona, Spain.

10. Prasanna PM, Siegel E, Kunce A. Greening radiology. Journal of the American College of Radiology. 2011 Nov 1;8(11):780-4.

11. Wormer BA, Augenstein VA, Carpenter CL, Burton PV, Yokeley WT, Prabhu AS, Harris B, Norton S, Klima DA, Lincourt AE, Heniford BT. The green operating room: simple changes to reduce cost and our carbon footprint. The American surgeon. 2013 Jul;79(7):666-71.

12. Jehle K, Jarrett N, Matthews S. Clean and green: saving water in the operating theatre. The annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2008 Jan;90(1):22-4.