12 minute read

& TEARS GRADUATION SINCE

2019

to solve problems. You’ve learned to work hard and give the extra effort to complete an assignment. You’ve learned to work with a team. You’ve learned to deal with adversity and failure and pick yourself up and keep going. You’ve learned to follow directions and be coachable. You’ve learned to keep going with dedication when it’s tempting to give up and quit. Go live your best life. Go live your dream. The best is yet to be. Congratulations, graduates.”

Advertisement

RCC Student Government President Gabriell McArthur gave the opening remarks, starting with thanking the staff at the College and her family for helping her reach the graduation milestone.

“To all the students here today: Well done. You made it,” she said. “I know that this journey has not been easy for you, and I want you to know that I’m proud of you. Everyone here is so proud of you. When you leave here today, whether you decide to go off to a university, to start a new career or even a new business, I want you to know that you can do it. Have faith in yourselves. You have all worked very hard to be able to walk across the stage today, and you deserve to be honored for your dedication.”

After Presidential Scholar Kassandra Ciriza Monreal delivered the invocation, Shackleford introduced McBrayer, and RCC Vice President for Instructional Services Suzanne Rohrbaugh followed McBrayer with the presentation of candidates for graduation.

“This is my favorite day of the year,” she said. “I love what I do. I love the students that we serve. I love the faculty I walk alongside of every day. Tonight is extra special because we’re able to celebrate the incredible success of all the new graduates. We can go down the list and talk about all the obstacles and the challenges — I probably should use the word ‘COVID’ every other word. So, if nothing else is on that resumé, you should say that you are extremely flexible. You all have demonstrated the perseverance and the determination to get here tonight. Thank you for allowing us to be a part of your educational journey, and we wish you the best.”

The graduates then crossed the stage one-by-one to receive their degrees, diplomas, and certificates. Board Chair F. Mac Sherrill announced the awarding of all three, and Williams closed the ceremony.

“Your being here tonight required much of you and those who supported you along this journey,” he said. “I encourage you to take a moment right now to look around with those sitting next to you, think about all your family and friends here with you tonight as well as all of those watching online. Capture this moment. As you go your separate ways, you will forever have a special bond as RCC graduates. Congratulations. You did it. We are so proud of you.”

By Megan Crotty

A year before the George Floyd protests in 2020, former Randolph Community College President Dr. Robert S. Shackleford Jr. had set a goal of revising the College’s Basic Law Enforcement Training (BLET) curriculum to include more diversity and de-escalation training for law enforcement. De-escalation is a range of verbal and nonverbal skills used to slow down the sequence of events, enhance situational awareness, conduct proper threat assessments, and allow for better decision-making to reduce the likelihood that a situation will escalate into a physical confrontation or injury and to ensure the safest possible outcomes.

In July of 2020, thanks to reserve funding, the North Carolina Community College System (NCCCS) started an Impartial Policing initiative in response to the protests of police use of force surrounding Floyd’s death. The content for the training was developed through the North Carolina Criminal Justice Education and Training Standards Commission and the North Carolina Sheriffs’ Education and Training Standards Commission with community colleges acting as the delivery agents.

Four regional instructor training events were held statewide in July and August, including at RCC, with 150 instructors taking part and then sharing the standardized impartial policing content with police departments and sheriff’s offices at no cost to the officers. The training extended additional instruction on implicit bias, impartial policing, and collaborative community engagement. Implicit bias training is designed to help officers develop awareness of their personal implicit biases, understand how those biases can influence their behaviors, and devise ways to prevent biases from leading to disparate treatment of members of the public, particularly regarding the use of force.

Thanks to these initiatives, RCC’s 88th Basic Law Enforcement Training class was one of the first to be given additional training that many new recruits do not receive. The class took courses in de-escalation and implicit bias — a curriculum designed by Derrick Crews, a 27-year police veteran and nationally-recognized de-escalation instructor.

“The Asheboro Police Department has really jumped on it,” former RCC BLET Coordinator/Instructor Brian Regan said, noting the College offers the training in Continuing Education as well. “Right now, you can just watch the news and see what’s going on. These agencies aren’t providing de-escalation training and de-escalation policies, and it’s really a liability. I try to make it a point to the students to one, stay updated on your training and two, don’t just sign off on a policy. You better read it and you better understand it.

“That’s the one thing I like about Derrick’s class is you can move between de-escalation, using force, and then go back to de-escalation.”

Regan, who chaired the Use of Force Board for the North Carolina Highway Patrol for three years, is well aware of the need for clearly written policies and staying within those guidelines.

“When people get into law enforcement, they think, ‘Oh, it’s an exciting career,’ they don’t think about the other side of things; it’s a high-liability profession,” he said. “You can’t do things outside of what you’ve been trained to do.

“One thing we run into with the younger generation is the communication part. They can send you a text all day long, but when it comes to actual face-to-face communications, they struggle. Hopefully, this will help them with being able to talk to people and not let emotions get in the way,” Regan continued. “[Derrick] shows them a lot of videos where officers let their emotions take over, and then they make bad decisions, and they end up using too much force. One thing I’ve realized working with the patrol is people will call and say, ‘I didn’t like getting a ticket, but they were professional.’ That goes a long way. Being respectful to someone, being professional, and listening to them. I want them to leave with that skill.” differently — calling for an officer who isn’t emotionally connected to the situation or who recognizes the signs.

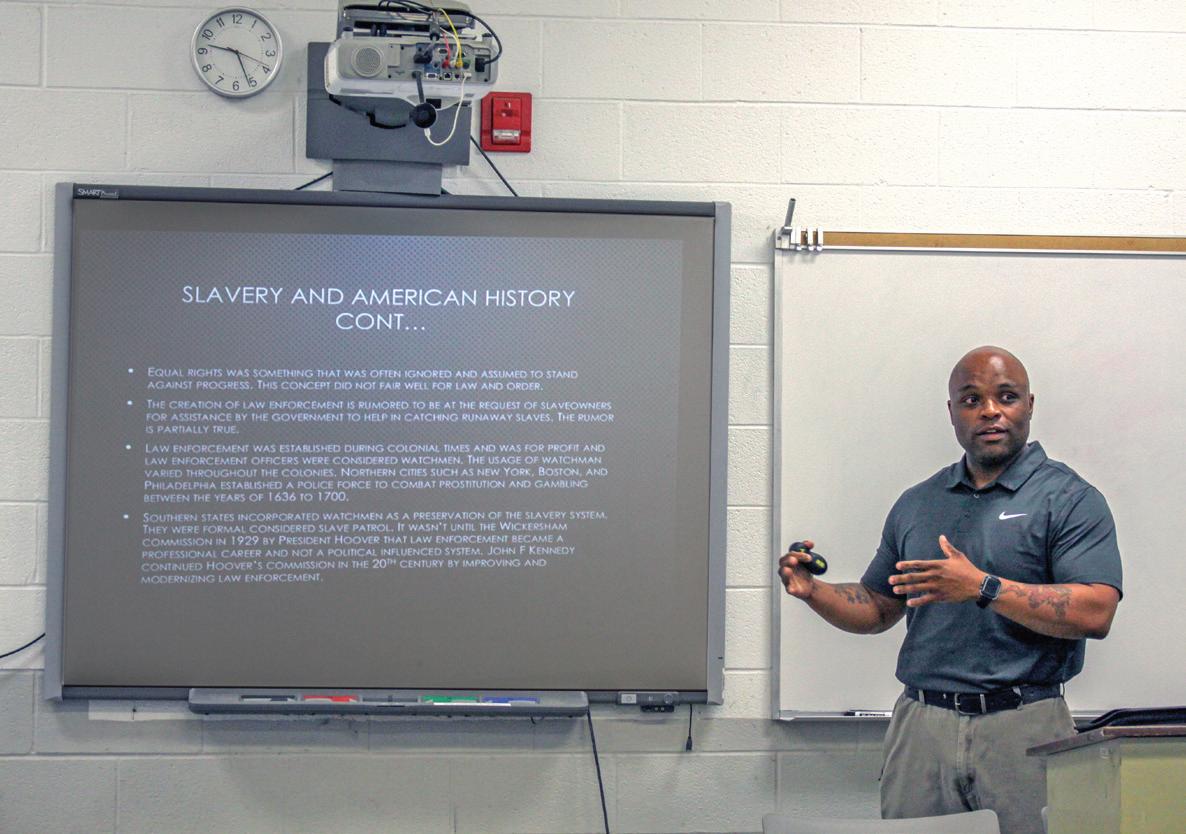

Sgt. Jerome Asbell of the Asheboro Police Department taught the implicit bias curriculum to the 88th class, starting with U.S. history and the origins of policing and its connection to slavery.

The curriculum is taught in the classroom — explaining what implicit and explicit biases are, what it means to be impartial, ethics, and the ways stress can impact officers on the job — and outside of the ESTC buildings where the new recruits are put into different scenarios they may face on the job, including traffic stops that get heated.

“One of the reasons why this class was created was deescalation — they never really teach how to transition from de-escalating to hands-on,” Crews said. “You don’t need to de-escalate with someone who wants to comply. The only reason to de-escalate is either they’re trying to bait you into doing something or they want to hurt you.

“When you’re de-escalating and that guy starts getting hyped up, you need to be like, ‘It really looks like you’re upset right now. Can you tell me a bit more about what’s bothering you?’ Set yourself up to where, if things go south, you’re a professional. You’re doing everything you can in your power to avoid confrontation. They chose the confrontation, not you. It’s about empowering officers with cognitive templates.”

Crews added that, when it comes to someone with a mental disorder, officers are taught to deal with the situation

“The history of America was wrought with bias,” said Asbell, showing the class a classified in an old newspaper advertising enslaved people. “They’re basically using people as property, as currency. Think about somebody who is in a predominantly Black community being raised by her grandmother who was raised by her grandmother who was actually part of slavery times. All they know is, ‘When I see law enforcement, they were slave catchers.’ When we got into it, we can’t go into it being biased, and we need to recognize our own biases.”

Outside, the officers worked on traffic stops with Crews and Sgt. Micah Lowe playing various driver roles — anything from a parent late picking up their child from school to someone on the phone to someone reaching for a weapon. Both stopped and instructed the trainee with suggestions on how to better deal with a situation and to tell the officer what they did correctly.

The scenarios included moments when the trainees may have to intervene when another officer on the scene needs to take a step back, or when they need to take a step back.

“Out of 100 cars I pull over maybe two are like this,” Crews said of the more difficult stops. “Every human wants to be cared for or see someone caring for someone else. If I’m not presenting a threat, say, ‘Hey are you OK?’ All you have to do is ask. It takes two seconds to ask.”

Lowe said the atmosphere surrounding law enforcement is much different from when he joined the force.

(Continued on page 10)

“When I came through, you didn’t get any of these trainings just due to the way society was at the time,” Lowe said.

“Still, this isn’t new. After Rodney King and a few more incidents, I started to do what we call verbal judo training. But, after September 11, this country became so patriotic in the sense of what’s right and what’s wrong that whenever I came through, we didn’t have any of this. It was — you ask them to do it, you tell them to do it, if they don’t, you make them do it. It’s a miracle many of us have survived without having to take someone’s life or something of that nature. But you learn from experience. There are plenty who’d never have made it because they didn’t have the skillset and it cost them the job over the stress.”

Lowe admits the training can get personal and the instructors use profanity, but it’s all to prepare the recruits for what happens on the job.

“If you’re short, if you’re overweight, if you’re older than the rest of us, if you look like you’re 12 years old, if you’re female, you’re going to be attacked for that on the street,” he said. “They’re going to exploit it. I’ve seen it time and time again. We’re going to do it out here; we’re not going to avoid it. We’re going to put you in a situation, so you know how you’re going to react to it and so when you get out there you don’t start seeing red.”

On the wrestling mats, students trained for situations when a suspect is on the ground. Lowe and Cpt. Justin Trogdon stressed communication — confirming non-compliance, telling the suspect everything that is happening, verbally de-escalating even when it gets physical, even introducing yourself.

“If you’re having a hard time at home and you’re not keeping your emotions in check, when you get out on a call and somebody says something that triggers you, we teach them there’s a level, white to black, where they want to stay in the middle,” Lowe said. “We’ve started putting them in a scenario much like some of the scenarios we’ve seen in recent American history. Maybe you’re doing a fantastic job and keeping yourself in check. You’re well aware of your own biases and you’re saying the right things, but perhaps, the other officer is not making the right decisions. Maybe his actions aren’t matching what our goal is. There’s a time to intervene. That’s part of de-escalation, too.

“I always found that, after an argument ensued, it's always easier for the officer who comes from outside that situation to connect with that person on a level where they can communicate and not make them any more escalated than they are. Sometimes I'll go on a scene and just me walking up and saying, ‘Hey man, how's it going?’ Sometimes he’s just happy to see somebody else.”

Recruits also learn how to deal with their own stress, discussing “saboteurs” — personality traits and personal situations that can impact an officer on the job. They even teach breathing techniques — another tool in the chest to keep the new officers calm.

Barrios looks to help community

Like many students who attend Randolph Community College, Jorge Barrios took a circuitous route to his chosen career.

Born in Cuba and raised in a tough Miami neighborhood, Barrios enlisted in the military before he graduated from high school in 2013. Unfortunately, he suffered a knee injury and didn’t graduate from boot camp. Barrios was told to let his knee heal and re-enlist.

While his knee healed, Barrios and his girlfriend (now wife) took a trip to North Carolina to visit her mom and stepfather.

“I just fell in love with the scenery, the nature, the tranquility,” Barrios said. “And you can get land and houses for a fraction of what they cost in Florida. My upbringing in Florida — it wasn’t the best neighborhood. It wasn’t a place where I wanted to bring a kid into the world. So, I moved up here. My mom’s been mad at me ever since.”

Barrios started working for his father-in-law, whose business services and cleans the sterilizing chambers for the surgical wing of hospitals. The job meant lots of travel, which Barrios found exciting as he got to see new places.

When the COVID pandemic hit, Barrios and his father-in-law were in New York.

“You would go to the hospital and see the trailers behind just full of the bodies,” he said. “It was eye-opening. Everything was empty; all the restaurants were closed. It was hotel, work, order food, work. There was no travel, no flying, no nothing. I got homesick at lot of the time.”

Barrios had already been considering law enforcement before he started working for his father-in-law. COVID and the birth of his son convinced him to change careers.

“I want to be not just his dad; I wanted to be a role model for him,” Barrios said. “It’s not just about me anymore. I want my son to grow up in a safe community environment. I wanted a little more job security, too.”

Barrios enrolled in RCC’s Basic Law Enforcement Training (BLET) program in January 2021. He was used to the physical parts of the training thanks to his short stint in the military, but his class was part of a new breed of law enforcement that was also trained in de-escalation and implicit bias — an initiative started by both former RCC President Dr. Robert S. Shackleford Jr. and the North Carolina Community College System in response to protests against those in uniform.

“When I went through BLET, the election [had] just happened, and everybody hated the police,” he said. “They were putting us in a lot of the situations that were coming out in the news. You realize, ‘Even if I have every right to use my hands in this situation, sometimes it’s best to use your

By Megan Crotty

words.’ It’s eye-opening, especially when you go through training. A lot of officers who get in trouble nowadays didn’t receive that training.

“Situations where you find yourself in a pickle and you think you’d react one way, but when it comes down to it, you think, ‘I really need to train more in this area.’ You revert to old habits and don’t do the proper technique. Your mouth can get you in a lot more trouble, but it can also get you out of a lot more.”

Barrios said that a lot of de-escalation is realizing that many times the person you’re dealing with is having their worst day and feeling hopeless.

“When you corner someone like that who is backed up between a rock and a hard place, you can try and not make them feel like they’re being cornered and there’s a way out of it,” he said.

Coming from a neighborhood in Miami with Hispanic, Black, and white residents, Barrios said it helped him better understand where people are coming from.

“I knew the streets already, but [to be in law enforcement] you have to learn how to talk to people,” he said. “You have to learn how to relax and not be so uptight. When I have the uniform on, I’m held to a higher standard. Because at the end of the day, you have to be professional, too.”

Wanting to be close to home after he graduated from RCC, Barrios took a job with the Randleman Police Department. Life on the force, like the BLET training, has been another eyeopener for Barrios. Police officers wear many hats — whether they want to or not. And not every call is an emergency.

“You sign up for the job, but you realize it’s a job plus dealing with people with mental issues,” he said. “So you’re a therapist, and you have to think about all the laws. You’re the state’s lawyer on the street. And you're the public’s punching bag. They’ll fight you. It gets crazy.”

The life of an officer can also get complicated when you are “different.” Barrios is not only Hispanic, but also stands at 5-foot-2. At 27, though, he’s used to the jabs.

“I always grew up with my brother and I fighting,” he said. In fact, Barrios said he is going to stick it out in law enforcement until he retires. In January, he started at the North Carolina Highway Patrol Academy.

“My favorite part of the job is traffic stops and working accidents,” he said. “It’s getting drunks off the road. Getting meth and heroine off the streets. I want to do more for the community.”