4 minute read

Come Again?

A historic Queen Village treasure embodies two centuries of adaptive and religious reuse.

By Margie Wiener

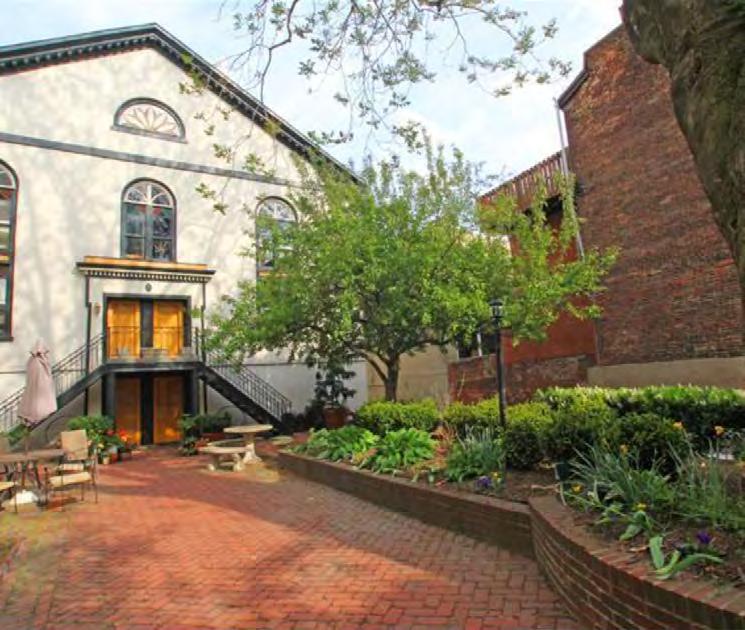

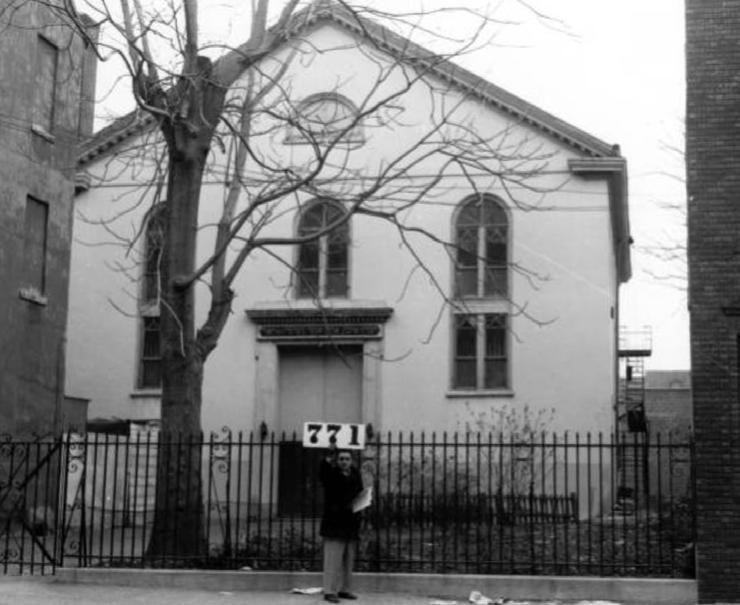

Queen Village is home to many impressive architectural structures, some with even more impressive stories to tell. Take the beautiful Neziner Court condominiums at 771 South Second Street near Catherine Street. From the outside, peering into this Federalstyle building through the wrought-iron gates, a passer-by will be amazed to learn that before becoming condominiums, this building had been successively used and reused by Baptist, Catholic, and Jewish immigrant groups over the course of 175 years.

Before 1969, when this neighborhood was known as Southwark, the first inhabitant of this sturdy meetinghouse, erected in 1811, was the Third Baptist Church. According to Harry Boonin, author of The Jewish Quarter of Philadelphia: A History and Guide, 1881-1930, the design of the majestic, rounded windows on the face of the building probably dates to the founding of the church.

During the Civil War, the church became a hospital for the wounded, who were homeward-bound. Unfortunately, many did not make it home, and the church pastor presided over funerals for more than 2,000 soldiers, including some who were buried right behind the church.

As newer immigrant groups made their way to the Southwark community, current immigrants and working-class residents began to feel threatened with displacement. By the mid-1800s, mostly Irish immigrants had settled in Southwark. The native Protestants were suspicious of their Catholicism and threatened by more competition for jobs. In fact, in 1844, three days of rioting broke out.

In 1870, due to political and social unrest, there was vast emigration from Poland to the U.S. By the late 1800s, the

Old Southwark area around 2nd and Catherine was heavily populated by Polish immigrants. This influx, along with the population of Italian and Jewish foreigners in the neighborhood, caused a decrease in attendance at the Baptist Church. By 1896, members of the Third Baptist Church asserted that they had been “driven from our field by foreign population” and sold their building to a new wave of immigrants. (Boonin, Jewish Quarter of Philadelphia, p. 112.)

In 1898, the First Polish National Society of Philadelphia became the second owners of the building. The Society believed in Catholicism, but as a splinter group of the Roman Catholic Church, its members did not subscribe to the authority of the Pope or the Catholic Church’s hierarchy. Such a dissident church proved unpopular with the surrounding devout Polish Roman Catholics. On May 23, 1902 (just four years after buying the building), the First Polish National Society of Philadelphia defaulted on its second mortgage, forcing the sheriff to sell the Church property.

Fleeing persecution in Eastern Europe in the 1880s, Jewish immigrants banded together in 1889 to form their own synagogue charter. Officially, its name was Congregation Ahavas Achim-Anshe Nezin, which meant Congregation of Friendly Sons of Nezin, a small town in southern Russia. In 1905, the Neziner Synagogue bought the building, and, over the next 25 years, its membership increased significantly. From various accounts, the congregation’s Jewish ritual began as Hasidic Orthodox and later transitioned to Ashkenazic to accommodate the congregants’ preferences.

Only minor changes were made to the 1811 structure because the building’s church design was easily convertible for synagogue use. These included removing the Baptist Church’s crucifix from the roof and erecting a new eastern wall at the back of the building that extended the sanctuary for the Jewish Holy Ark (into which Holy Torahs are traditionally placed). All these changes enabled Neziner to accommodate 800 worshippers in a small space.

The Baptist Church’s graves were disinterred and reburied elsewhere. The resulting lot in the back was used as a play yard, and the south side plot of ground was used for a sukkah (a temporary hut covered with branches, built for a fall festival that commemorates the 40 years the Israelites spent in the wilderness). The front courtyard provided botanical splendor.

Following WWI, the familiar pattern of community shifts recurred, with some immigrants prospering and moving to newer parts of the city, such as Strawberry Mansion, Logan, Wynnefield, and West Philadelphia. The remaining members, whom some would interpret as disgruntled by what they saw as abandonment, were “less affluent men, sort of old-guard conservative men who refused to accept any changes for Conservative Judaism, or programs for youth or women.” (David Kraftsow, History of the Neziner Synagogue.) Membership declined, and the building, its mortgage unpaid, fell into a state of disrepair.

Surprisingly during the Depression, the synagogue experienced a rebirth under the leadership of Isaac Schreider, a new member who lived in the neighborhood. Schreider cleverly fundraised from former members who had moved away. Under his leadership, the synagogue was remodeled considerably. In addition, Neziner adapted to changing times by forming a sisterhood that flourished for many years, introducing more modern Conservative services by adding English to the Hebrew prayers, developing programs aimed at young people, and allowing women to sit with men on the main floor of the sanctuary.

Just before WWII, Dr. John Craig Roak, the Minister of the Old Swedes’ Church, located at Water and Christian Streets, began interfaith services with the Neziner congregation. Although interfaith services continued for years, they could not prevent the ongoing trend of wealthier congregants emigrating to the suburbs. In the post-WWII era, attendance and membership declined at Neziner Synagogue.

Furthermore, initiated by Mayor Dilworth and growing throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the process of gentrification began in Queen Village’s northern neighbor, Society Hill. Gradually, as young families moved into the gentrified neighborhood, the membership of Society Hill Synagogue expanded. This boded poorly for Neziner Synagogue and its aging membership.

By 1983, only 50 families were left. Neziner was sold to and absorbed by Temple Beth Zion-Beth Israel at 18th and Spruce Streets, where its Ark doors and other artifacts are now kept and its Hebrew school is aptly named Neziner.

Today, the Neziner Court Condominiums occupy the building. A straightforward structure, the building was converted into eight spacious residential units in 1985. It remains set off from the street (as it was years ago) by a courtyard and wrought-iron fence.

In 2013, Hidden City Philadelphia, an online publication that explores obscure yet captivating heritage and architectural sites, named Neziner building among the Top 10 sacred buildings in Philadelphia to be used for other, non-religious purposes.

This local recognition, combined with a distinguished listing in 1958 as a National Historical Landmark by the National Preservation for Historical Landmarks (when it was still Neziner Synagogue), highlights the uniquely rich, weaving story about these three immigrant communities (Baptist, Polish Catholic, Jewish) adapting and readapting to life at the Neziner Building at 771 S. Second Street in Queen Village. ■

• Experience

• Commitment

• Hard Work

• Enthusiasm

• Integrity

• Qyeen Village Resident

Our commitment to your happiness is the foundation from which a solid business relationship is built. Simply put, your satisfaction is our greatest reword. Our business hos been built on solid and unwavering foundations, and we look forward to putting our expertise to work for you. Success Doesn't Happen by Accident!