7 minute read

Pulse Publications #23 - January 2024

The Civilizer OF THE WEST

FREDERICK HENRY HARVEY was born June 27, 1835. He immigrated to the United States from England with his parents in 1853 at age 17. He found a job scrubbing pots at the popular Smith and McNell’s Restaurant in New York City. He worked his way up through dishwasher, busboy, waiter, and line cook. He learned the restaurant business there. But, more importantly, he learned the importance of good service, fresh ingredients, and the handshake deal.

He later moved to New Orleans and then to St. Louis where he worked in a jewelry store. He married in 1856. He started a café with a partner that was doing well until the Civil War began. The partner, a supporter of the Confederacy, headed south with all their money. Financially ruined, Fred began working for the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad which was later bought by the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad.

Once again, he worked his way up the corporate ladder. One promotion included a transfer to Leavenworth, Kansas. In this position, he traveled extensively by rail. He was disappointed with the very poor choices of meals available to rail passengers at that time. Passengers had to scramble during the short stops the train made to take on fuel and water, to buy what they could find and hurry back to the train.

In 1873, he opened two eating houses with a partner, Jasper “Jeff” Rice. The eating houses were 280 miles apart along the Kansas Pacific Railroad. Although the restaurants did well, that partnership failed as well. Fred then took over the twenty seat lunch counter upstairs at the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe station in Topeka, Kansas. The first thing he did was order new plates, linens, and flatware. And, of course, the food was made with the freshest of ingredients, and service was first class.

The success of that one small lunch counter led to a handshake deal with the superintendent of the AT&SF to open a few eating houses along the railway. The railroad built the rent-free facilities and delivered fresh meat and produce in their Santa Fe Refrigerator Dispatch cars. The steam trains needed to stop every one hundred miles to take on fuel and water. By the late 1880s, a Fred Harvey dining facility was located at each one. At the time of Fred Harvey’s death, in 1901, there were forty-seven Harvey House Restaurants, fifteen hotels, and thirty dining cars serving his food. The railroad advertised “Fred Harvey food, all

By John Wease

the way.” This was a play on their slogan “Santa Fe, all the way” that referred to the longest railway in the country.

Fred Harvey is credited with creating the first restaurant chain. He also started the first chain of hotels. In reality, souvenir shops, book stores and newsstands could be included as well since all could be found at his facilities. His hotels offered fine dining to the middle class and upper-class travelers in dinner jacket required dining rooms. The elegant dining rooms were equipped with fine China dishes, highly polished silverware, and Irish linen napkins. More casual dining rooms featured large, horseshoe shaped counters that predated the iconic American diner. An 1880s menu listed a “blue plate special,” a daily special at a reduced price. Blue plate specials were widely known some thirty years later. Meals were organized to such a degree that hundreds of passengers could be served every twenty minutes.

Fred Harvey is referred to by some as the founding father of the American service industry. His methods are studied to this day in programs of hotel and restaurant management, marketing, and advertising. He named his company simply “Fred Harvey.” This seemingly unimaginative name was a brilliant marketing strategy. After his death, his son, Ford Harvey, ran the company for much longer than Fred had.

To the customers, they were still eating Fred Harvey’s meals, cooked and served the Fred Harvey way. Almost as though they believed Fred could stop by to make sure everything was done correctly.

One of Fred Harvey’s innovations, and perhaps the best known, was initiated in 1883. Fred was a hands-on kind of leader. Never one to run his growing business from his home in Leavenworth, Kansas, he frequently visited his facilities. The story has it that he entered one of his restaurants one morning to find his entire male staff hungover, dirty, battered, and bruised, from an evening of drunken brawling. Someone suggested he hire women as they didn’t drink and were always on time. Okay, I’ll say it. Oh, how times have changed.

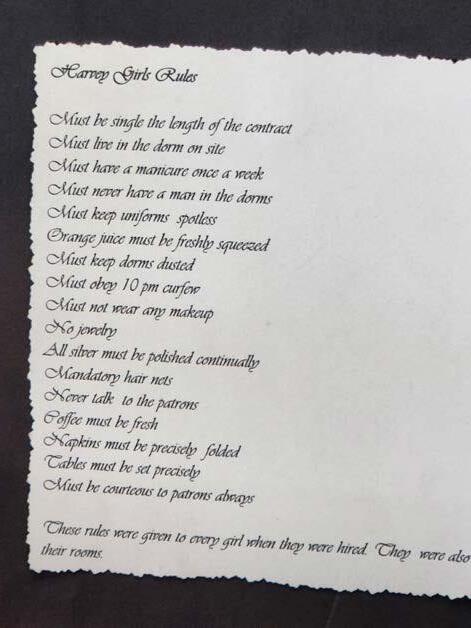

Fred placed ads in midwestern papers for single, white women, ages eighteen to thirty. Other qualifications were that they must be attractive, of high moral character, intelligent, and with at least an eighth- grade education. For the contracted period of employment of six months (there are references of nine and twelve-month contracts as well) the young women would receive $17.50 per month, room and board, and “liberal tips customary.” Dormitory style housing was provided with a senior waitress serving as a dorm mother to enforce the strict curfews.

The girls wore black dresses (no shorter than 8” off the floor, and in no way flattering) with stiffly starched white aprons. No makeup or jewelry was allowed. Hair was tied up and all wore a big white bow. Each of these “Harvey Girls” set tables precisely, kept silver polished, served customers in a professional manner without fraternizing. Thousands of eastern and midwestern girls went to the Wild West to become Harvey Girls. It is unknown how many found husbands among the business men and ranchers that ate meals in the Fred Harvey restaurants. It is said that having the Harvey Girls present created a mood of civility and helped maintain tranquility in dining rooms full of sometimes rowdy western characters. These classy young

women certainly played a large part in earning Fred Harvey the nickname of “civilizer of the West.”

Fred Harvey played a large part in promoting tourism in the Southwest. From a small display of Native American jewelry in the Gallup, NM restaurant grew an industry of Native American jewelry, arts and crafts. Souvenir shops at Fred Harvey eating houses likely led to the numerous souvenir shops that were found along the old Route 66 and a decorating style known as “Southwestern.” The early Harvey Houses were simple wooden structures to keep costs down for the railroad. Near the end of Fred Harvey’s life, the railroad embraced more elegant styles. Spanish or Mexican-influenced designs that are now referred to as “Santa Fe” style. El Tovar, his elegant hotel on the south rim of the Grand Canyon was just breaking ground at the time of his death.

Fred Harvey’s home in Leavenworth, Kansas is now the Fred Harvey Museum. A number of historical museums in the towns where his restaurants were located have collections of Fred Harvey memorabilia. One hundred and twenty-two years after his death, he has a large number of fans that call themselves “Fredheads.” Every famous person needs famous last words. There are two versions of Fred Harvey’s last words.

Fred Harvey sold sandwiches to those that wanted something fast they could grab and go. Ham, or cheese, were the choices and made with three slices of bread. At fifteen cents, the sandwich was considered a great value. One version of the story is, as his sons stood around his deathbed, he said: “Don’t cut the ham too thin!” He was well-known for offering generous portions so this could well be true. The other version, related by employees was: “Slice the ham thinner, boys!” Either way, it is interesting to think of this English immigrant that embraced the American entrepreneurial spirit, created what would become the sixth largest food service company, and died concerned about ham sandwiches.