7 minute read

Question of harm reduction

By Rory Harbert

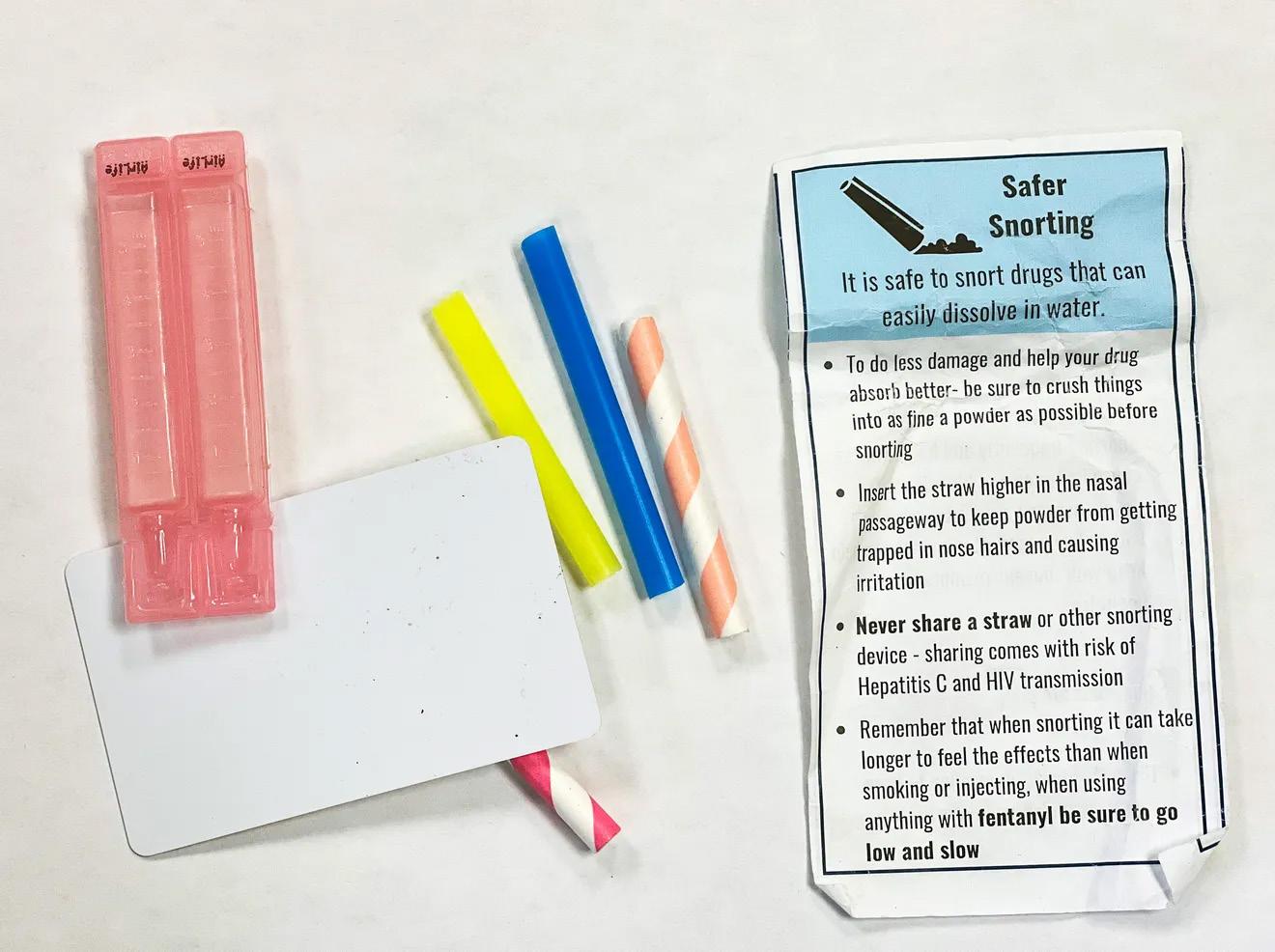

In February, the Board of County Commissioners released a statement following a work session presentation by The Pueblo Department of Public Health and Environment concerning county-specific substance use data. The commissioners took the opportunity to address their concerns with a “snorting kit” from Access Point, a statewide syringe-exchange program hosted by the Colorado Health Network.The kit includes pre-cut straws and a bare-bones infographic on safe administration. With the PDPHE unable to speak for the syringe exchange programs, the commissioner board released a statement in opposition of the programs’ kits.

Advertisement

Commissioner Eppie Griego has taken a firm stance against this tactic of harm reduction being used to address Pueblo’s substance use epidemic, saying that this “crosses the line between harm reduction and drug promotion.”

Aligning with Griego’s views on the issue, the press release states, “The Board of Commissioners condemns the materials and vows to take steps to license and monitor the nonprofits who provide needle exchange programs.”

Additionally, the press release states that the board will be “taking steps to ensure that any non-profit promoting needle exchanges will not receive county money.” The press release explains that there are only two organizations that provide syringe access services, and neither currently receives money from Pueblo County.

While Griego has made his views clear, other board members were not quoted directly in the press release.

Upon reviewing the recording of the county commissioner afternoon work session in which the PDPHE presented to the board, much of what is included in the release was verbatim in the work session, but not by Griego. Commissioner Garrison Ortiz took a strong stance on regulating syringe exchanges.

“I truly believe you need more permitting to run a coffee shop than you do a needle exchange,” Ortiz said.

Ortiz said he needed to see an exchange rate that reflected a 1:1 ratio, or close to it. His concern was where the “spillover” needles, or the needles that are given out but not returned, went. Ortiz said that “I know people know what they see, in our parks, in our community, in our neighborhoods,” suggesting that not all the needles get returned.

Griego, quoted in the press release, said “the large assumption in our community is that these needles are exchanged and not left in public areas.” According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, people who inject drugs in areas with syringe service programs were shown to be “more likely” to dispose of syringes safely.

These services work within the treatment philosophy of “harm reduction.” The National Harm Reduction Coalition defines harm reduction as “incorporating a spectrum of strategies including safer techniques, managed use, and abstinence to promote the dignity and wellbeing of people who use drugs.”

Jude Solano, the cofounder and CEO of Southern Colorado Harm Reduction Association, wanted to address these concerns and provide some clarification on what role the needle exchange programs play in the Pueblo community.

“We want people in treatment,” Solano said. “That’s part of the misinformation, people not realizing that we are trying to get people in treatment; we provide it on site. We are very successful. It’s hard to definitively say, but I know for SCHRA—we’ve gotten hundreds of people in treatment. Hundreds. Now whether they stay in treatment or not, that’s on them. But when they come back, they’ve relapsed, we get them back in.”

The association does not provide only needle syringe exchange. They also pro- vide:

Working LEAF, or the Life Empowerment and Fulfillment project for underserved youth and re-entering citizen; CRAFT, or the Community Reinforcement and Family Training, support; WAGEES, or Work and Gain Education and Employment Skills program, in partnership with CDOC and LCCL; RE-Entry post-incarceration support; and The MOM grant provides services to pregnant people for a “healthy pregnancy.”

While the safe-snorting kit came from Access Point, SCHRA provides similar kits during the exchange hours. Solano said that the information is not meant to teach how to use but rather follow the principle of harm reduction: encouraging safer techniques. As the National Harm Reduction Coalition states, “we recognize that using drugs introduces risk – but there are ways to make it safer.” The National Harm Reduction Coalition explains that IV injection is “the riskiest method to use in terms of overdose (as compared to sniffing, smoking, or oral administration) because the entire dose enters the body all at once and very quickly.”

“People know how to use,” Solano said. “We want people to transition from injection to smoking. It’s safer. It cuts down on endocarditis, which can be a life-threatening cardiac illness. It cuts down on wound issues and tissue damage and all the illnesses and acute healthcare emergencies that occur with IV drug use. We provide the supplies for people to transition.”

Solano explained that sharing of straws can lead to communicable diseases, which is also one of the reasons why the syringe exchange program was implemented.

“What we do is we give them extra supplies, so they don’t share equipment,” Solano said. “You can get Hep-C from sharing a straw. If somebody is infected, and you come in contact with their nasal secretions, you can get it.... this is a public health service, and it’s related to decreasing those communicable diseases.“

According to the National Harm Reduction Coalition, “there are numerous and potentially very serious health complications associated with injecting illicit drugs, from injection-related injuries like tracking and bruising, to bacterial and fungal infections, from communicable diseases, to drug overdoses and other medical emergencies.” These complications come from “drug-related, technique-related, and hygiene- related mishaps,” but, as these are “black-market, unregulated drugs,” people can take steps to improve technique and hygiene.

According to the CDC, syringe service programs are “associated with an estimated 50% reduction in HIV and HCV incidence.” The CDC, building on this statistic, states that when combined with medication-assisted treatment, “HCV and HIV transmission is reduced by over two-third.” Medication-assisted treatment, or MAT, utilizes the Federal Drug Administration-approved medications buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone along with therapy and counseling to treat opioid use disorders. SCHRA partners with Front Range Clinic, which provides MAT services on Wednesdays.

Griego stated, in the press release, that he spoke with local law enforcement officials and said “there is long-standing concern with the practice involving the needle exchange programs in our community” and “should these activities spill over into the criminal realm, they will be investigated and prosecuted as appropriate.”

Southern Colorado Harm Reduction Association reported a 91% average weekly-return rate in 2021. Which led to over 270,000 used needles exchanged in the program to be properly disposed of, which is counted by weighing the tubs of needles they take in rather than counting each syringe, as that would pose a health risk to the staff. SCHRA is only open for the syringe exchange for one day during the week, for four hours at a time. At this time, this is the only service provided. Additionally, the CDC cites two studies, performed in Baltimore and New York City in 2000 and 2001 respectively, finding that there was neither an increase nor a decrease in crime rates between areas with or without syringe service programs. A 2013 study, cited by the CDC, showed that syringe service programs, after referring clients to medication-assisted programs, that “new users of SSPs are five times more likely to enter drug treatment and three times more likely to stop using drugs than those who don’t use the programs.”

“We are not encouraging drug use, drug use is happening,” Solano said. “We want people to be safe and we want them to have an environment where they know we are going to provide direct access to healthcare and treatment when they ask for it.”

According to the release, “Griego believes both needle-exchange organizations need more oversight.” Griego aims to achieve this by starting a “pilot program to hold Pueblo’s two nonprofits accountable if their needles are found in public spaces.” This would mean needles from those organizations would be marked, and if they are found within the county, “law enforcement and regulators can take action to hold these organizations accountable.”

The Pueblo Department of Public Health and Environment conducted a presentation on the substance data collected for Pueblo County for the commissioner work session on Feb. 14. The presentation included data breakdown information such as the working population, or the age group that makes up the bulk of the workforce, is most affected by fentanyl overdoses in the county.

Within the presentation, the PDPHE said their website includes, beyond the data dashboard, a peer-support database and opioid use awareness and education. The PDPHE also shared its efforts to reduce stigma via the “Empower to Recover” campaign, which the department called “Your Words Have Power.”

The health department website states that PDPHE “believes that using words to empower rather than stigmatize and provide our community with resources is how we can reach those goals.”

Anne Hill, public health epidemi- ologist representing PDPHE, said “prevention is critical” in reply to the board’s concerns about stopping drug use to begin with.

“We are collecting some of that data that’s related to root causes,” Hill said. “What is truly fostering some of these issues? Is it housing, education? We know, you know. Inherently, you know… We need to start thinking through those pieces too. So, we are totally in agreement related to prevention.”

Not wanting to speak for harm reduction organizations, Hill wanted to emphasize that the PDPHE looks at numbers, but the syringe exchanges would provide more information that the board was looking for in the comments and questions period post-presentation.

Hill said “there is so much new science related to addiction and to substance abuse” that would indicate that this is “like a chronic health issue” and believes that Dr. Michael Nerenberg, vice president of the Pueblo Board of Health, would agree.

“(So) to get them out of that takes so much will power,” Hill said. “It is really, really hard. So, we need to focus on making sure we have the healthiest possible community for these individuals.”

Both Ortiz and fellow commission member Zach Swearingen were contacted for further comment. Ortiz was contacted by email and phone, but did not reply by the publishing of this article. Swearingen was approached in person but did not provide commentary beyond what was provided in the press release.