23 minute read

A selection of book reviews

REVIEWS

Out of Time: Poetry From the Climate Emergency Simpson, K. (ed) Valley Press, 2021. ISBN: 97871912436613, 142 pages, paperback, £12.99

Advertisement

Kate Simpson writes in her introduction to this important collection of poetry, which she has also edited, that ‘Out of Time engages with the power of poetry to ask questions, subvert expectations and raise awareness in 2021’. She points out that the anthology has been very definitively ‘datestamped’ as having been brought together in 2021, because it explicitly rejects the notion that poetry can be timeless, relevant to all eras and audiences. For Simpson, the poems here invoke the true power of ‘ecowriting’ which is ‘about using language to relearn our direction on the planet not as one of sovereignty but of responsibility—of co- and interrelated existence with the non-human’.

Out of Time: Poetry From the Climate Emergency is grouped around specific themes and concerns: emergency, grief, transformation, work, rewilding.

The first section, entitled ‘Emergency’, explores in a visceral, eye-opening fashion ‘unimaginable ecological realities’. The opening poem of ‘Emergency’ (and the whole collection) is ‘New planet who dis?’ by Rishi Dastidar. It is a stream of consciousness riff on our destructive behaviours:

‘stone pebble that Galileo dropped next to the feather like that straight down spirit level down plumb line down lift shaft down oh maybe Tower Inferno is somewhere in this mix too remember all the flames up the lift shaft Faye Dunaway’s eyebrows shoot up anyway the point is down i’m going down...’

For me, the most telling poem in the ‘Emergency’ section is Cath Drake’s ‘What I’m Making With the World’: ‘I’m making a handbag out of the hide of the world I’d been hunting for something contemporary, unique. It gutted and skinned fairly easily: the soil, rivers, oceans, seams of hot tar, broken glacier chips and molten yolk fell out into a pile that I’ll take in a sack to the tip.’

The almost playground quality of the first line takes a sinister steer as the poet embarks upon a ‘hunt for something contemporary, unique’. Throughout the collection, there is a deep sense amongst the poets about how complicit we all are in the earth’s destruction.

Hannah Lowe’s ‘The Trees’ is a wonderful contrast to Philip Larkin’s bucolic poem of the same name: ‘All summer the trees in the park have been plummeting down. Most wait until dark, when the skaters and smokers and dealers have made their way home’

Lowe’s Anthropocene urban pastoral gives agency to the trees, which ‘wait’ for their moment to plummet. Many of the poems in the collection similarly personify the earth, but there is nothing coy or Disney like about this personification; it’s more that personification is used to provide agency to nature. It indicates a new sense of holism in nature writing; the poets do not perceive themselves as separate from nature but rather they are in it; immanence is the name of the game here. It’s as though the Cartesian dualism of mind/body, humans/nature have been emphatically replaced by the idea that we are all intimately connected in both knowable and unknowable ways. This outlook provides many of the poems with a richness and originality which is often absent from much nature poetry.

In the ‘Grief’ section, Gboyega Odubanjo writes in ‘Oil Music’: ‘we in the black, we both in a barrel. call it a village. we both in the pumping. the people no get no nothing’

The themes of social justice and the climate emergency are admirably represented in the collection. As in ‘Oil Music’, the voiceless are given voice, the powerless are taken seriously, they conveyed the power of their experiences. Equally, the non-human is focused upon. There are poems about butterflies (Fiona Benson), the origins of the modern rose (Sarala Estruch), and ones that also feature fishing as an imaginistic thread (Romalyn Ate and Andrew Fentham). The closing poem of this section by Linda France is about the Giant Sequoia in New York’s Natural History Museum. The last two lines are particularly compelling: ‘I swear I can smell the forest where you were felled – ancient and piney, earth’s incense rising.’

This is what these poems do to the reader as a whole; they provide a kind of ‘incense’ from the earth—the smell of our planet rises off most of these poems. In the section on ‘Transformation’ Raymond Antrobus asks at the end of his poem ‘Silence/Presence’: ‘What would the trees say about us? What books would they write if they had to cut us down?’

Again, there is an important personification going on here. The reader is invited to imagine a world where trees can speak and write, and have the power to ‘cut us down’. As with many poems in the anthology, we are drawn into a parallel world where non-humans are conveyed in a capacity rarely accorded in any other forms of thought. This is what poetry can uniquely do; set us thinking on different pathways.

Ella Frears undergoes the most profound transformation in this section in her poem ‘Becoming Moss’: ‘I lie on the ground I open my mouth. I suck on a spoon. I embrace a stone. I empty my mind I stuff it with grass I’m green, I repeat’

I love the insouciant humour and mystery here. Frears poem both debunks ‘greenwashing’ and celebrates it. In poems such as these, we are permitted to think two contradictory thoughts at the same time: to see the futility of much of our attempts to ‘connect’ with nature, but also to perceive and feel the necessity and elliptical meaning in it. In the next section, ‘Work’ Inua Ellams’ poem ‘Fuck/Humanity’ curses modern life, and Will Kemp appoints David Attenborough as his PM when he goes abroad. In ‘Geography Lessons’, Mariah Whelan poetically explores her teaching about soil erosion and Fair Trade, and concludes: ‘…extinction might not be the world ending but a correction, righting itself of its heavy, human tilt.’

Quite a few poems do express this anti-humanistic approach; they pulse with humanity’s self-hatred and self-loathing. They are difficult, sobering poems to read.

In the final section, ‘Rewilding’, Martha Sprackland goes beach combing and remembers: ‘…When I was younger, desperate for a place to call my own, I’d scour the pavement

on the way to school, head down, scuffing, for money to add to the shoebox

The poem is entitled ‘Savings’ and explores what can be saved from the earth in the era of the Anthropocene in a poignant, oblique fashion. This poem really works in the way it combines personal description of a beach littered with both human and natural ‘savings’. In ‘I am a person’, Dorothea Lasky talks about how she told the afternoon she is a ‘person from the future’: ‘It was the afternoon of the world The window winter light an endless ravine Outside the window…’

The poem evokes a definite sense of the uncanny as does the last poem in the collection ‘Leaf’ by Send Hewitt. These two poems also share a mystical optimism in their endings. ‘Leaf’ concludes: ‘For even in the nighttime of life it is worth living, just to hold it.’

It is a fitting end to a triumphantly potent and cogent collection of poems. This is a truly wonderful anthology; it contains poems by some of our finest poets, weaving very well-known names with poets I hadn’t encountered before. For me, it takes an admirably ‘decolonised’ approach both in its choice of poets and its thematic threads; you won’t find colonialized visions of the English pastoral here; the self-serving nostalgia for the ‘good old days’ or an imaginary golden age of ecological utopias. Rather, you will uncover a constant interrogation of what it means to be part of web of life on earth in 2021. I really appreciate the care that has been taken to construct this anthology, even though it is ‘date-stamped’, I feel it will be relevant for many decades to come.

Reviewed by Dr Francis Gilbert. Francis is a Senior Lecturer in Education at Goldsmiths, University of London. He has published articles about ecoliteracies in ‘Writing in Education’, (2021: Issue 83): https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/30308/1/Whats%20Next%20Ecoliteracies%20 FGilbert%20March%202021.pdf He is the Principal Investigator for the Parklife Project, which aims to get young, disadvantaged people to research their local parks and change them for the better using creative, innovative research methodologies. He has published three novels and writes poetry.

Sing Ho! Stout Cortez: Novellas and Stories Thomas, Michael W. Black Pear, 2022. ISBN: 9781913418-54-0, 224 pages, paperback, £8.00

Sing Ho! Stout Cortez is an intriguing title, and the book is made up of several intriguing stories and novellas, set in different locations and with very different characters, but deftly linked together by Thomas’s poetic and accomplished literary style.

The first story, the novella Esp, was shortlisted for the UK Novella Award in 2015, and expands on the experiences of Henderson Bray, first encountered in ‘Misshapes from Cadbury’s’ in Thomas’s story collection The Portswick Imp. It creates an excellent opening to the collection, introducing us to Thomas’s mellifluous style in a beautifully written coming-of-age story that follows a group of friends as they discover their roots and the power and of music, in the Caribbean island of Grenada. ‘We were at an age for a thirst for drama,’ we are told early on, and this thirst is quenched for the reader by the energetic and rich use of dialogue including vernacular nuance (translation notes are provided) and references to pop culture and music traditions. The sense of mystery and curiosity regarding one’s peers, that is so often a part of being a teenager, is well developed, revolving around the question of what happened to key musician and talent, Esp. Here, Thomas adopts a lightness in his writing which leaves the reader plenty of room to speculate—as Henderson himself says: ‘May be I sound mad, but this piercing it all together is more fun than downright fact.’ And, for me, Henderson’s narrative voice was so authentic and compelling that it was easy to keep in step with him and end up caring, like him, about what happened to Esp.

In the preface, Thomas talks of the unifying theme as the characters search to escape current circumstances (or the impact of past events on their present reality) and there is no one that has more of a right to seek escape than the narrator in the second novella, Tickle, Tickle. The narrator attends a writing group where friend Tracy is reading (‘It was funny, really, seeing your best friend in a new place and saying things in a new way, like half of you is rooting for her and the other half doesn’t know her at all’) and here, the main theme of the story is foreshadowed by a member of the writing group who refers to the topic of domestic abuse. Thomas takes us deep into the narrator’s consciousness as we learn of her experiences as a teenage victim of sexual assault and rape. The details up to the tragic climax are heartbreakingly sketched through her own young voice (‘I asked Mum if I could wear my jeans for the next visit, but she said not on your nelly’) emphasising the regret and mistaken complicity she feels in the act, increasing our sympathy for her. Through skilful writing, Thomas manages to create a realistic but satisfying end to this gripping story.

Thomas’s skill is his ability to fully inhabit each of his characters and show us their internal workings. In certain sections, however, it can feel like the internal monologue digresses a little too far from the action, which makes the story less compelling and harder to follow; that said, Thomas is a skilful enough writer to return us to the heart of the story in the end where he creates satisfying, nuanced endings that leave us thinking about the characters and their predicaments long after the book has ended.

Reviewed by Nicole Moody. Nicole Moody has spent over 20 years working in the study abroad sector, first as a programme manager and later as an academic. She is Associate Professor and Academic Advisor at the American Institute for Foreign Study (AIFS) based in Kensington, London and along with teaching she is responsible for AIFS’s student mentorship programme.

A Wonder Woman Kohli, K. Offa’s Press, 2021. ISBN 978-1-9996943-6-4, 80 pages, paperback, £9.95

When the poet Kuli Kohli was a child, she loved ‘free family days out’ in the Black Country with her brother and sister, and her dad, ‘his own boss on a double-decker bus’. In ‘On the Buses’, one of the standout poems in this compelling debut, Kohli uses Punjabi Black Country dialect to show how language changes landscape. Dudley becomes Dada-jee—meaning Grandad; Merry Hill is Meri-hal—My plough or tractor. Kohli observes her father in the mysterious world of adults: ‘blonde and brunette women/ in tiny dresses and high heels giggled, ‘How am ya luv?’/ Replying in his Indian accent, ‘I am very fine, lav.’ When they ‘ey gor enof’ pennies, he lets them on for free. But there are other passengers too: ‘young skinheads boarded/ shouting, ‘Bludy stinkin Paki! Rag head! Tekkin ower jobs!’ Sometimes he carries on, ‘like he was deaf’; other times he swears back.

This was Britain in the 1970s, when Wolverhampton-based Kohli, appointed this year as the city’s poet laureate, arrived as a small child with her parents. The tender ‘A Piece of India’ acknowledges their struggle. A young Indian woman, wearing her best clothes, her ‘vibrant colours smudged in shadows of charcoal’ goes to the cinema for ‘a touch of gold dust’, her baby clinging to her hip. ‘Porcelain dolls sway in the wind, fearless like the rain’: white women, who call out insults. But, Kohli insists, ‘They exchange gentle nods in a cultural clash.’ Her parents’ resilience and grace means that, ‘A generation later, that baby, that child made in India/ a lost mosaic piece glinting… [is] An ideal fit in the Black Country’.

Kohli is big-hearted and humorous. She recognizes the female battle to hang on to identity, among the demands of family life: A Woman Like Me ‘should/ get up in the early hours,/ prepare and cook good food,/ get kids ready with magic powers.’ Yet she admits, I don’t know/ a woman like me,/ I only know me.’ She has an extra difficulty to overcome: she was born with cerebral palsy. In ‘Life Under Lock Down’, with time to think, she imagines living in a

war zone: ‘as an Asian disabled woman/my life would not have been worth much./ Here umbrellas give me shade, keep me dry.’

She does not shy away from examining her disability. In ‘Wedding Day’ – ‘the day I thought/ would never come’— she wonders, ‘Could someone really accept me as a wife?/ Maybe as a sacrifice?’ She’s given her husband’s ring to hold: ‘With a sudden spasm and a jerk,/ I dropped it!’ They watch the ring ‘roll away like a penny, like a dream’. In another poem, Equilibrium, she writes, ‘I survive crossing roads, bridges,/ tree roots, rocks and uneven slabs;/ collecting coppers, notes, a diamond earring/ on my travels, people’s lost possessions.’ Adventure comes at a cost: ‘I barely look forward or above;/ all I have to lose is my balance.’

Some of Kohli’s most vivid images are inspired by nature. In ‘I Wonder’, she walks ‘among the gossiping trees; / evergreens clothed in prickly shades of jade,’ under ‘the blue sky wired with branches’, hearing ‘cold secular silences, broken by roaring chainsaws’. Closer to home, she’s puzzled by a Chile Pine, an ‘exotic creation/ like industrial chimney brushes,/ with stems like giant cactuses.’ She wants to know ‘why and how/ these Chilean gauchos live/ so comfortably in a tarmac garden.’ She asks her neighbours, but ‘The family, who had moved recently/ into our estate, were obsessed with drinking,/ weddings, expensive cars and big houses,/ never answered my questions.’

Many women might have felt, during the pandemic, that they had to be Wonder Woman. For Kohli, the feeling is not new: she’s a survivor, who, in her poem of the same name, ‘entered the world like an uninvited guest’. She was ‘different – an alien from outer space’. Her marriage prospects made her feel like ‘a British visa for Asian men to chase’. Yet she has made a happy marriage, and family life, and found her place – as ‘a valued writer, poet, working mum’. As she acknowledges, ‘I survive this sentence – a tough test’.

Reviewed by Sarah Hegarty. Sarah Hegarty’s short fiction has been published by Mslexia, Cinnamon Press and the Mechanics’ Institute Review, and shortlisted for the Fish and Bridport prizes. She has an MA in Creative Writing and is writer-in-residence at George Abbot School, Guildford. She is represented by Annette Green at Annette Green Authors’ Agency. www.sarahhegarty.co.uk

How to Write Short Stories and Get Them Published Lister, A. Little Brown, 2019. ISBN: 97811472143785, 244 pages, paperback, £9.99

Books about the writing process are plentiful. If you want advice about how to make a character believable, there is a multitude of books on offer to help. The same applies to plot. And setting. In fact, writers are spoilt for choice when it comes to books about their craft, so much so that it can, at times, feel overwhelming. Ashley Lister’s How to Write Short Stories and Get Them Published fits perfectly into the ‘support guide’ category—and it does what it so clearly says on the cover.

Lister is well-established in his field, and he has been published in many magazines, anthologies and academic journals. He lectures in creative writing and this ‘how to’ book is proof of his skills and experience. It is a superb example of a text that ably amalgamates what we, as writers, look for: each of the nine sections tackles different areas of short story writing, or challenges, and is followed by an exercise. For example, the first section, titled ‘Ideas’, is followed by a number of different sub-sections, such as ‘Writing Prompts’—and then, an exercise is provided. One of the main selling points of this book is the breadth of ideas it covers. As a writer myself, I often look for a quick fix—and this book provides such a treat, although, of course, there is no obligation to complete all the activities; it is a case of picking and choosing what works best for the reader.

The nine sections cover the well-trodden paths of fiction writing, ranging from ‘Point of View’, through to ‘Plot’, as well as ‘Editing’. The final section focuses on how to pursue publication, along with entering competitions and persevering—something we can all struggle with from time to time. There are also some helpful refreshers, such as ‘Freytag’s Pyramid’, and this is one example of how Lister incorporates the theoretical into the practical. I find this helpful in different ways, and I am sure that readers of this book will feel the same.

One of the beauties of such a guide is being able to dip in and out of sections that hold the most appeal—or aim to provide some sort of resolution for the reader. I sometimes struggle with dialogue, for example, and one of the exercises in the ‘Characters’ section asks different questions. The intention here is to force the reader into thinking about how a character would speak, and how might they address different people. Being forced into being reflective is useful—but having guidance ahead of new writing is also of great benefit.

Lister references a wide range of books throughout, and examples include The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, when discussing narrative viewpoint; Keats’ ‘To Autumn’; and, the much more contemporary Conversations with Friends, Sally Rooney’s debut. Even though several the references do not pertain to the short story, the message is the same, whether it is about dialogue, as it is in the latter, or something else.

How to Write Short Stories and Get Them Published is a perfect addition to any writer’s desk, regardless of their experience. Established short story writers can learn a lot here, but so can those who view the form as some sort of bête noire, which is sometimes the case for writers who craft in the long form. Regardless of experience or knowledge, this is a very useful book and one that I will return to time and time again.

Reviewed by Matthew Tett. Matthew Tett is a freelance writer living in Wiltshire. He has been published in Writing in Education, the Cardiff Review, the New Welsh Review, and Ink Sweat and Tears. His short story ‘Spun Sugar’ was published in the inaugural edition of Liberally. In 2021, he won Word After Word’s mini memoir prize. He is also the coordinator of StoryTown. Matthew is currently working on his debut short story collection.

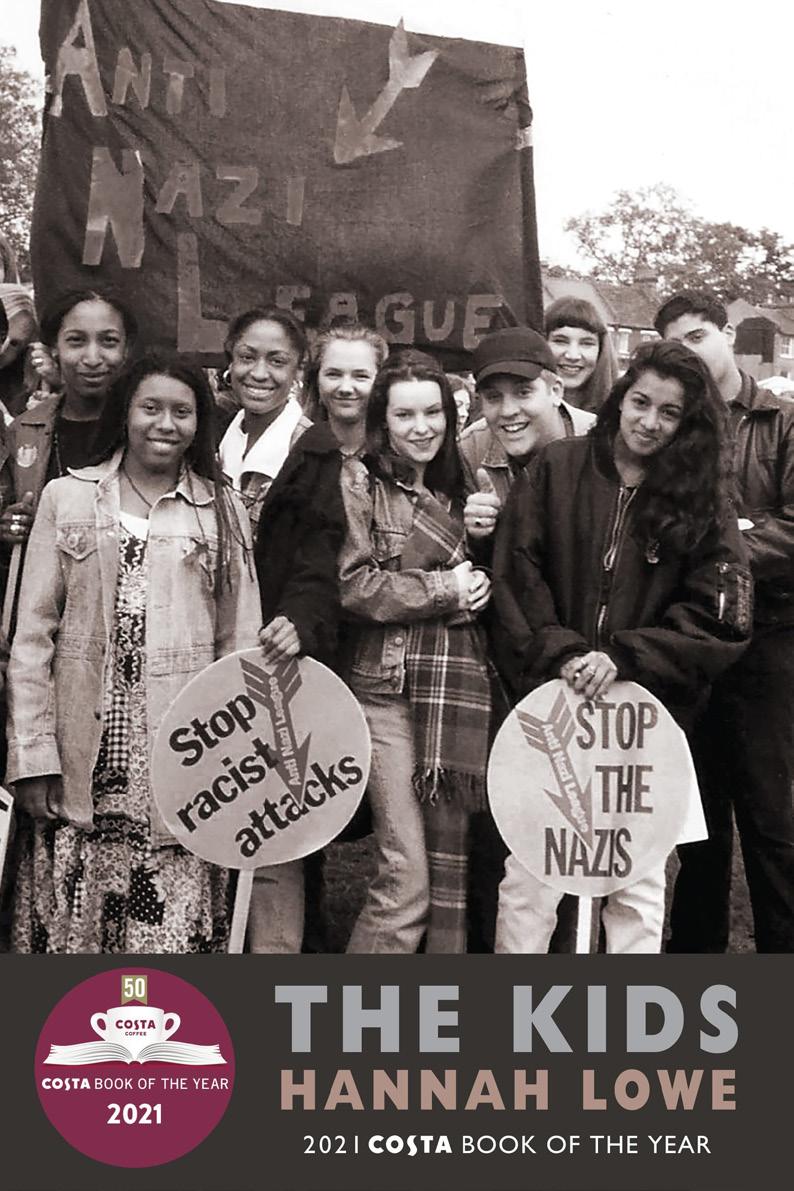

The Kids Lowe, H. Bloodaxe Books, 2021. ISBN 9781780375793, 80 pages, paperback, £10.99

Ask any teacher about the best—and worst—aspect of the job, and they’ll invariably say: the learners. The students. The kids. Now poet—and former schoolteacher—Hannah Lowe, a guest speaker at NAWE’s recent conference, has made the kids the focus of her third collection. The power imbalance between student and teacher can make such an enterprise tricky; but Lowe pulls it off with respect and compassion. In sonnets that sing off the page, she expresses the joy, fear and frustration of the classroom relationship.

In ‘The Art of Teaching [part] I’, “before I’d learnt the art of teaching wasn’t/ to have all eyes on me, but on each other” Lowe is unsparing of herself: “I sat behind my desk and talked and talked/ like a manic newsreader, while their faces balked/ in boredom or horror, and one by one glazed over”. Even in part II, she despairs: “Boredom hangs like a low cloud in the classroom. /Each page we read is a step up a mountain/ in gluey boots. Even the clock-face is pained/ and yes, I’m sure now, ticking slower.” What’s the answer? In part III, she identifies two approaches: “Squeeze/ their names out like a flannel. Swap their chairs/ and split the windows for a freezing breeze”; or, “study them—what’s in their bag, their walk/ to school, their grandmother in Tower Hamlets/ or Istanbul.” She might have got to know her kids, but she has no illusions that she’s cracked the classroom dynamic. With the

insight that only experience can bring, she warns, in ‘Red-handed’ that “if you set the kids exam practice/ then excuse yourself—even for five minutes— […] to eat a Twix, or bite your hand to keep/ from crying” you might come back to a quiet classroom, but “know how quick/ the kids can zip their chat, though leave it hanging/ in the air so you can smell it”.

There are so many fresh and funny, affectionate images in these poems that each page is a delight. Lowe has said that she ‘wanted to give a very honest view of the working life’. It’s that honesty that makes her vulnerable, often with unintended consequences. In ‘All Over It’ she and her student Dwayne are discussing his project on graffiti, and she tells him about her older brother, “years back, spraying one train then another/ with a jangling sack of cans he’d robbed/ from Homebase and wire-cutters from the shed.” Her student’s reaction makes the reader squirm for her: “You tell Dwayne this/ but he’s backing out the room, Yeah, nice one, Miss –”

She worries whether she can make any impact at all. In ‘Balloons’ she writes, “But the kids I taught, who came to me at the edge/ of childhood – was it really, then, too late?” She describes how “In the common room we said it only took/ one class, one hour, to know the grades they’d get”.

The students come alive on the page, although Lowe has stressed that the portraits are fiction: each a composite of students she’s known, meshed with her own experiences. She’s also explained that the demands of the sonnet meant she had to invent, to achieve rhyme and metre.

The collection isn’t solely classroom based. In ‘White Roses’, Lowe is cleaning her mother’s house after her death. She pulls out the mattress and finds, “the ring she said was stolen; a fort/ of crumpled tissues, white roses wet with crying.” There’s also a lovely section of poems dedicated to her young son. In ‘Skirting’, he “rides these streets in his battered pram/ like a prophet, his milky arms spread open, / face first into the world.”

There’s so much to enjoy here that it’s no surprise the book won Lowe the 2021 Costa Poetry Award, as well as the overall 2021 Costa Book of the Year—a remarkable feat for a poetry collection. Lowe has described how she came late to poetry, and started writing while she was trying to enthuse her own students. There’s a humility here—but also love fitting for a book of sonnets.

Reviewed by Sarah Hegarty. Sarah Hegarty’s short fiction has been published by Mslexia, Cinnamon Press and the Mechanics’ Institute Review, and shortlisted for the Fish and Bridport prizes. She has an MA in Creative Writing and is writer-in-residence at George Abbot School, Guildford. She is represented by Annette Green at Annette Green Authors’ Agency. www.sarahhegarty.co.uk

NAWE is a Company Limited by Guarantee Registered in England and Wales No. 4130442 and a Registered Charity no. 1190424

Staff

Director: Seraphima Kennedy

Participation Director: Fiona Mason f.mason@nawe.co.uk

Information Manager: Philippa Johnston pjohnston@nawe.co.uk

Publications & Editor Manager: Lisa Koning publications@nawe.co.uk

Membership

As the Subject Association for Creative Writing, NAWE aims to represent and support writers and all those involved in the development of creative writing both in formal edication and community contexts. Our membership includes not only writers but also teachers, arts advisers, students, literature works and librarians.

Membership benefits (according to category) include:

Management Committee (NAWE Board of Directors)

Andrew Melrose (Chair); Anne Caldwell, Derek Neale; Michael Loveday; Lucy Sweetman; David Kinchin (co-opted)

Higher Education Committee

Andrew Melrose (Chair); Jenn Ashworth; Yvonne Battle-Felton, David Bishop; Helena Blakemore; Celia Brayfield; Jessica Clapham; Sue Dymoke; Carrie Etter; Francis Gilbert; Michael (Cawood) Green; (Paul) Oz Harwick; Andrea Holland; Holly Howitt-Dring; Derek Neale, Kate North; Amy Spencer; Christina Thatcher; Amy Waite; Jennifer Young

Patrons

Alan Bennett, Gillian Clarke, Andrew Motion, Beverley Naidoo

NAWE is a member of the Council for Subject Associations www.subjectassociations.org.uk • 3 free issues per year of Writing in Education • reduced rate booking for our conferences and other professional development opportunities • advice and assistance in setting up projects • representation through NAWE at national events • free publicity on the NAWE website • access to the extensive NAWE Archive online • weekly e-bulletin with jobs and opportunities

For Professional Members, NAWE processes DBS (Disclosure and Barring Service) checks. The Professional Membership rate also includes free public liability insurance cover to members who work as professional writers in any public or educational arena, and printed copies of the NAWE magazine.

Institutional membership entitles your university, college, arts organization or other institution to nominate up to ten individuals to receive membership benefits.

For full details of subscription rates, including e-membership that simply offers our weekly e-bulletin, please refer to the NAWE website.

To join NAWE, please apply online or contact the Membership Coordinator: admin@nawe.co.uk

NAWE Tower House, Mill Lane, Askham Bryan, York YO23 3FS +44 (0) 330 3335 909 http://www.nawe.co.uk