22 minute read

TIME and the TOWN: A Conversation with Painter Salvatore Del Deo and Poet and Historian Josephine Breen Del Deo

TOWN and the TOWN

A Conversation with Painter Salvatore Del Deo and Poet and Historian Josephine Breen Del Deo

Sal and Josephine Del Deo have lived and worked in Provincetown more than sixty years.

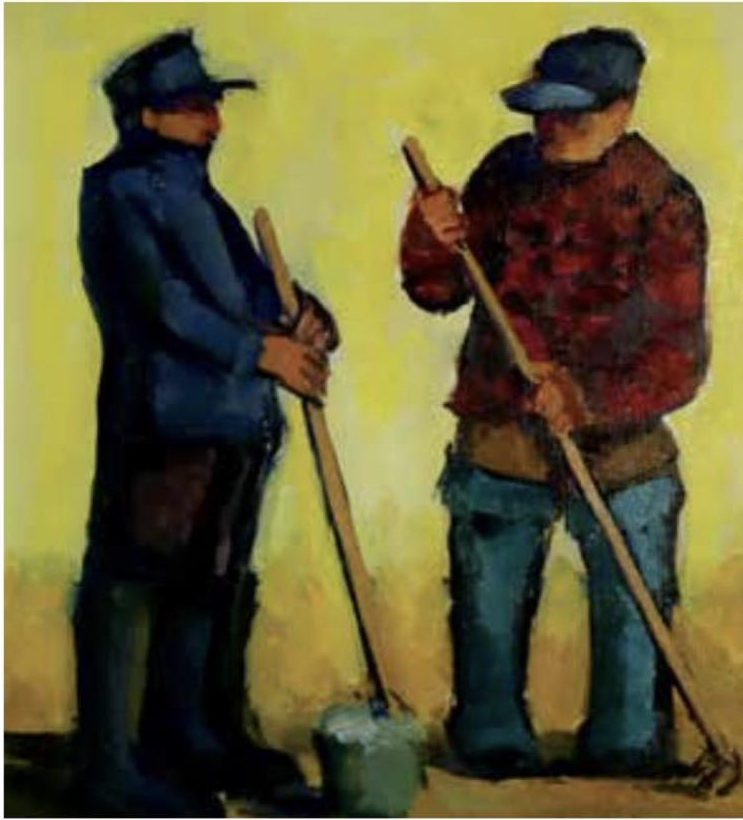

Sal is a prominent painter, whose powerful representations throughout the years of the town’s working people and compelling landscapes, are represented in major museums and private collections world wide.

Josephine is a noted historian and poet whose numerous books include "Figures in a Landscape," a pivotal biography of painter Ross Moffet, "The Watch at Peaked Hill- Outer Cape Cod Dune Shack Life 1953-2003" as well as many essays and books of poetry.

The pair have counted among their friends some of the most notable artists and writers to have ever lived or spent time here.

Their years of dedication and passionate commitment to the town of Provincetown have left it a much better place and created for them – and for us – a remarkable legacy.

Art Guide: You’ve been here many years. If you were to go into your mind’s eye and let some images percolate up and reach your psyche, I’m curious what would be the first to come forth?

Josephine: Probably the landscape is the first thing that comes to mind, because it’s such an unusual landscape. It’s compelling, it’s almost hypnotic. Once you come over the hill and you see Pilgrim Lake for the first time, you never forget it. And, of course, the harbor is magnificent. So that’s the first image that I can draw, that never changed its importance in my life here.

Probably one of the reasons that I love the dunes so much is the beautiful isolation, the quiet, the tranquility, just the majesty, and so few people can be a part of that, no matter where you come from or what you’re doing. Most people never get a chance to get more than a few days or a few weeks. But I got to live here!

Art Guide: It’s infinite space, really.

Josephine: Right! You need infinite space, you need what William James called a “wide mind-field” where you can relate many, many things. So that’s number one.

If you bring up an image that could be secondary to that, it would be the absolutely charming nature of the town – I once described it as a string of pearls along the beach, and it was so beautiful. The images were so varied. And the amazing thing was the fishing industry was at its peak. So you kind of had this European sense of a working fishing town, and it wasn’t phony, it was really real.

Art Guide: I want to just follow up on this idea of the spaciousness of this town. Because interestingly over the years people will come to visit me here in the off-season and say “How can you live here, there’s not enough stimulation!”

Josephine: If you’re a person who is vitally wooed by what you think, and what you want to do from a philosophical point of view, then your value system is entirely different from the person who has to be entertained. And that’s why I think this town saw so much art. There’s so much space that you can expand your vision.

Art Guide: Sal, when you think of your time here, what is the first thing that comes to mind?

Sal: Well, my experience of Provincetown was predetermined long before I ever came here. It’s funny because when you talk like that people think you’re kind of crazy or something. But, as a matter of fact, when I was a kid I had two brothers. The one nearest my age, five years older than me, died, unfortunately, when he was nineteen years of age. Years later when I was going through his papers, I saw one of his essays from high school, and it was called “Provincetown: A Fisher Town and a Painter Town.”

My brother came here when he was maybe sixteen years old, and he was so taken by this place. He said to me “Sally-“ (they called me Sally in Providence) – “I went to a place where there’s fishermen and boats on the beach. And it was so colorful.” He said, “There were painters right there, painting these wonderful scenes… someday you’re gonna go there, I swear to God.”

I’m one of the few people who came to this town not because of the lifestyle, but because I had a definitive idea of studying with somebody who I thought could teach me how to paint. I would have gone where Mr. Hensche (Henry Hensche, painter and director at the Cape School of Art) was. And they told me he was here, so I came here.

Art Guide: How did the two of you meet?

Josephine: Sal knows this better than I do.

Sal: When I got out of the service in ’53, the first person I met on the street was Harry Kemp (writer and poet), who I had known since I was seventeen. So I saw him and we embraced and we talked, and he said, “I found your mate for life.”

So I said, “Yeah, but is she pretty?”

He said, “She’s beautiful. And she’s a poet. And she plays the violin. And she is a wonderful person.”

“Where is she?” I said, “I want her.”

He says, “Well, we’ll have Shakespeare’s birthday party at your studio, and I’ll invite her to come up as my guest.”

So we had the party at my studio. My studio was on the water. And nine o’clock came, and I went up to Harry. All my painting student friends, guys and gals were there drinking the cheapest wine you could drink – no drugs, just wine – and so I went up to Harry and I said, “Harry, where’s your friend? I don’t see her.”

He said “Oh Salvatore that’s not like her. I’m sure something must have come up.”

And finally there was a knock at the door and there’s this figure in the doorway, an American Indian female dressed in Indian clothes with beads and stuff.

I said “Can I help you?” She says “Are you Sal?” I say “Yeah.” “Well Harry invited me to a party here. I’m sorry I’m late because I’m a campfire leader. We had just had our pow wow, and I had promised the girls a picnic at New Beach (in those days it was called New Beach, not Herring Cove) and we had a wonderful fire, and this is the earliest I could get away.”

So that did it. At the end of the party I said, “I’d like to see you again.” And she said “Oh, maybe it could be arranged.”

So I borrowed Ciro’s (Ciro Cozzi, painter and co-owner of Ciro & Sal’s at Kiley Court) car and we drove out to New Beach, and we talked and spooned and got to know each other. And that was the beginning of it. That was May, and we were married in November.

Art Guide: I’ve often believed that Provincetown calls us. Provincetown calls to certain people. Can you sketch a portrait of what this town was like when you married and settled here. What sort of lifestyle did you have?

Sal: It was a working town, that’s the difference.

Josephine: It was a working town but there were so many of us that were on the same working level as artists. I mean, every shop sold a craft like leather, jewelry, ceramics, weaving… They were all craftsmen that lived here and did their work here. And that was so exciting.

Then you had the galleries like the Sun Gallery, a magnificent experimental gallery. And then the theater. So it was high-energy, high-participation. There was never a moment when you were bored by anything.

Sal: I was very happy to know that this was a working town. Painters have always been attracted to working people.

Van Gogh, he went to the mining parts of Belgium, and lived with the workers, and then he started portraying them, because I think that generally painters like me - I associate with people like Van Gogh - because they have the strong socialist kind of concept of humanity, you know? And it’s always stuck with me, from the times I read Zola and those wonderful writers.

So this town offered me this, you know? And I loved it. I knew I could build something here. I could create something here that Hawthorne (Charles Hawthorne, founder of the Hawthorne School of Art in 1899) had started. That marvelous person who saw the rugged beauty in these fishermen and their wives and their children and their whole environment.

I could see a sort of window there of something that I could do. You learn your skills and then you say, well what are you going do with these skills? Well, you can add to the visual imagery, but that’s not what real art is. Real art is the journey of discovery, of going from here to there and exploring all the little side streets and all the faces and everything else that you see in the course of a day.

Art Guide: I can’t help but look past you at that magnificent painting on the wall. I believe it’s Long Point, with that big wonderful cloud. So the landscape is obviously incredibly important to you.

Sal: Of course. I was talking to Howard Mitchum (artist, poet and cook) once, and he was looking at my painting of Long Point, and he said “I know what that is. You see the Long Point as the metronome of Provincetown.”

And I said, “That’s exactly right.” Because if you go to the east end of town, you’ll see the lighthouse. You go to the extreme west end of town, you see the lighthouse there. So the lighthouse, either east or west, is a metronome.

Art Guide: I like the fact that often in your paintings of Long Point, it’s this very tiny epicenter of this greater space. I like that you create this incredible atmosphere.

Sal: Well I did this on site, you know. It’s not done from photographs. In the fall, we have these marvelous cloud formations. The difference between our clouds and the clouds in Europe is that in Europe they’re painted in the sky, they never move, because there’s very little wind. Basically, as in Italy and Greece and Spain, they hang there. But here in Provincetown, the very end of this land, the clouds are always coming and going, coming and going. They’re always moving, you know? It’s a very interesting part of the landscape.

Josephine: The landscape here for me is endlessly exciting because it gives me all kinds of room to think the thoughts that I have and to expand. And it has nothing to do with the landscape ever being static, because the brain is not static.

Dickinson (painter Edwin Dickinson) said this great thing that I put in the book on Moffett (painter Ross Moffett). He said, “Painting is what a thought does to sight.” It’s the thought that does the thing that you want to put on paper. It’s not the landscape, it’s what the thought does to the landscape. And I don’t think that any painter has ever said it any better. Lots of people don’t understand Dickinson’s paintings, even though they know he’s great. But he interpreted his landscapes… sometimes there’s so little there.

Art Guide: His work is so visceral, I think.

Josephine: A sensitive man. He came to paint on the wharf towards the end of his life at Sal’s Place. They were very close. We were close. I loved Dick.

Art Guide: Is that what you called him?

Sal: Oh he insisted. If he loved you, you had to call him Dick.

Josephine: He always called Sal, Del. Sal was very close to him.

Sal: There are books and books, legendary stories about Edwin Dickinson.

Art Guide: You’ve both known so many remarkable people, extraordinary painters and characters.

Sal: I’ve been so blessed. I’ve known such wonderful people that have been influential in forming my philosophy of life. One of them is Harry Kemp of course, who introduced Josephine to me. He was the one who did it. And of course I’ve known Henry Hensche, and I’ve known intimately Edwin Dickinson, Ross Moffett, Karl Knaths, Raphael Soyer (Raphael Soyer, the painter), I didn’t know him too well but I knew Hofmann (German painter Hans Hofmann), Stanley Kunitz (poet) I knew intimately… so they’ve all been part of my fabric. They made me what I am today, actually.

Art Guide: And what was your relationship like with Harry?

Josephine: We were very good friends. He was an intensely scholarly poet, and a good one. His early works are quite special. He’s highly underrated.

Art Guide: Poet of the dunes.

Josephine: Yes, well, people will never forget that, but the author William Brevda wrote an excellent biography of Harry Kemp entitled The Last Bohemian.

Sal: You want to read something great, read his book.

Josephine: It’s a beautiful job. He interviewed me at some length, and he did his research. He wrote a classic piece. It does Harry justice.

Art Guide: And some of the other artists you were friends with?

Sal: We knew so many.

Josephine: It was like thick soup with really wonderful people.

Sal: It’s like your food that you eat everyday. You vary the menu, but the food nourishes you. Every day that goes by you meet somebody else and that nourishes you.

Josephine: I’d say that your biggest influence would have been Henry (Hensche), and then Dick (Edwin Dickinson). And Karl Knaths was a very close friend. Very dear.

Sal: I loved that man. He was a wonderful person.

Josephine: He and Arthur (painter Arthur Cohen- this year’s Art Guide cover artist) were the best of friends. Arthur was always in our house.

Sal: We used to go painting together all the time. He was always here. One year, he stayed at ‘The Home at Last’, 101 Commercial St, our property directly across from our restaurant, Sal’s Place at 99 Commercial St., and he’d have supper with us almost every night. He’d read to the kids from Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer. He was great with mimicking voices, he was wonderful.

Josephine: He used to come out on the dunes with us a lot. We were out on the dunes and all of a sudden a huge kite appeared over the horizon. And under it was Arthur Cohen. He’d made this kite. He was flying it for the children. It was so beautiful.

Art Guide: You’ve had a great opportunity to stay out at a dune shack for years- Frenchie’s Shack. Tell me about that.

Josephine: It meant everything to us. Frenchie was… I don’t know how you’d describe Frenchie. (Frenchie “Chanel”- actress, artist, bon vivant). She was amazing.

Sal: She came to Provincetown in 1930. She came with Bette Davis, the actress. They were friends from New York, in show business. They came down here and I saw this photograph that Shatzie (Frenchie’s daughter) showed me of Bette Davis and Frenchie in front of this great big roadster car, you know, one of those touring cars that were very popular.

Frenchie said to me once, “We went out to the dunes, and I said to Bette, ‘Bette? I’m staying. What about you?’” with a French accent. And Bette said, “No, I’m going back to the city, I don’t want to stay here.” So that’s what happened. Bette went back, and Frenchie stayed.

Art Guide: What is it like for you to spend time in that shack?

Josephine: Well it’s been a core of much of our creative life. Sal too, he always paints out there. It’s just reinvigorating. It’s interesting with us, because the painter, especially a painter like Sal, who has a narrative capacity which is second to none, he has the outer eye. He also has the inner eye and that defines him as a metaphysical painter as well.

My world is greatly inner, by comparison. The only way that a poet and writer has a chance to develop one’s inner resources, generally speaking, is by isolation and devotion to the inner eye. That component is very difficult to achieve in any circumstance, but privacy and solitude is obtainable on the dunes and a precious component of a poet’s life.

Harry Kemp had this one sign on his door. “Please do not disturb this property. There is nothing of any value here except solitude.” He meant it. That’s why he went back every time he could.

Art Guide: I walk on those dunes and I am completely revitalized. If that land wasn’t preserved, I would not have a purpose here, personally. You were key figures in preserving that land.

Sal: There were hundreds of house lots planned. Imagine if Ross Moffett and Josephine and I, plus many others, especially artists and writers, had not fought to save the Province Lands. What would we see today? A hotel, a heliport, a golf course- the works.

Josephine: It took us two and a half years to save the Province Lands. If it hadn’t been for Ross Moffett we wouldn’t have saved them. I joined him, and we really became a team. Speaking of the artists, we had about seventy-five people on our committee, most of them artists and writers. The park has truly saved the Cape. There would be no Cape Cod as we know it, it would be impossible to live here.

Art Guide: Sal, you have to take me on a little detour down the road of the restaurant years.

Sal: Oh yes. My cousins in Italy couldn’t understand how I could be a painter and have a restaurant – it’s inconceivable in Europe. You do one thing or the other. But I said, in America, that’s one of our great opportunities and privileges, that we can earn a living doing something else, because you have to develop in order to sell your product. It takes time to do that. In Europe they’re more funded by the state and the city, you see.

So we started this restaurant called “Ciro & Sal’s” but neither Ciro nor I were professional cooks. We were just rank amateurs, but we were sincere. What we put on the table, and what my mother and father would put on the table, or what his mother and father would put on the table, people loved it.

We started out very modestly, just making Italian sandwiches, which later ended up with omelettes, because people would come from the bars. There’s always been a historic place in town for the late-hours people.

We were very successful, and our partnership lasted until 1959 when I decided to try to make a living by doing odd jobs and selling paintings. However, in 1962, that idea proved unworkable, and so I started “Sal’s Place” at 99 Commercial St. in the west end of town.

Art Guide: And you were able to manage your painting and the restaurant?

Sal: Yes. I never stopped painting. I painted all through the years that I worked at the restaurant. I never stopped. I couldn’t have done it without Josephine’s help and support.

Josephine: The four of us worked as a family. (Sal and Josephine, their son Romolo and daughter Giovanna.)

Sal: When we had the restaurant, one day a week I used to hire a model. A half a dozen people would come and we’d all draw from the model. Then we rented the place across from the restaurant and we had a gallery there called Front Street Gallery, together with Dominic and Yvonne Falcone of the Sun Gallery. We showed art films there. We had Peter Schumann (founder of Bread & Puppet Theater) do his puppet shows there.

Art Guide: The reality is that Provincetown has changed since you’ve been here. It is a very expensive town to live in. I did want to ask you what you see and what you hope for.

Sal: What I always tell people is that what Provincetown has done, unfortunately, has destroyed its farm team. Now if you know baseball, the great baseball clubs have tremendous farm systems. That’s the spawning grounds of the future players in the major leagues.

I came here in 1946. This town was loaded with hundreds of kids from all over the country studying painting. It was beautiful. Whether it was realism or abstraction or whatever, they were here to paint.

They were the farm team. We were the farm team. You know, it was ten years before I ever showed a picture. Hensche always taught, you’re here to study, not to show. And he was right.

Josephine: When Sal came here at seventeen, he was penniless. He was with his friends, Ciro and Charlie Cooper, and they rented a place for almost nothing, and they cooked their own meals.

Sal: It would be difficult to do that now.

Josephine: You’re never going to see what we saw here. Not even in altered terms. The law of economics may move this town into another phase. It’s become so precious. When I worked on the historic district, I didn’t think of it being precious. I thought about preserving some of the really fine old buildings, but now it’s all become very precious.

Art Guide: Sal, you were instrumental in helping to create Cape Cod Tech and you both are founders of the Fine Arts Work Center whose intent was to give young artists an opportunity to work in this environment without financial restrictions. Do you see some other hopeful solutions for keeping this a vital community?

Josephine: I think the best solution that I’ve seen is the Center for Coastal Studies because that relates to the water. And I think we have to stay there because there’s a vast opportunity now. A lot of things can link to this. Laboratory work in this town should be reasonably successful because they’ve got everything out here to work with. I was kind of hoping that the Center eventually would get big enough that they could link up with Wood’s Hole Institute.

Art Guide: What do you think you’ve left the next generation of artists and residents of this town?

Sal: I’ve left my son (noted sculptor Romolo Del Deo) and my grandchildren here. It’s up to them to carry it on. I think my son will. But it’s always going to be more difficult to live here as I lived here. The bay is still there. It’s the same bay as we and our predecessors saw. The light is the same. The people, the cast is different.

Josephine: It’s interesting, because in order to keep any kind of traction between this generation and what we had as the previous generation… there was a lot of continuous trajectory. It wasn’t the same, but it was built on the same value system.

Now we live in a world where most of that value system is totally shattered for one reason or another. We cannot reform this town along the lines that we once had available to us. It has to be entirely different. There has to be an awareness of the planetary spectrum of which America is a part.

We once had a special consensus and concentration here that gave us a beautiful flight into this space, but nobody is going to experience that again until we can restructure the collective conscience of the country with functional equanimity.

Interview published in the Provincetown Art Guide, 2016.