8 minute read

Luther’s legacy

Luther's legacy

Gordon Campbell looks at how influential Martin Luther was in bringing the Bible to ordinary people, and highlights an upcoming conference commemorating 500 years since he published a New Testament in contemporary language.

Five hundred years ago this September, at the 1522 Leipzig Book Fair, a new volume went on sale with an inaugural printrun of 3,000 copies. This was a New Testament in German, printed not by any recognised press from a great city but by a newly-established printer from smalltown Wittenberg. It was an immediate bestseller: copies were snapped up and it quickly sold out; public clamour for more led to a thoroughly revised reprint coming out in December 1522.

Although no translator’s name even appeared on its cover or inside, every purchaser of this September Testament (as it was dubbed), or its December reprint, knew they were getting their hands on the work of Martin Luther. Luther’s name would adorn later editions soon enough, as early-modern Europe’s book markets were flooded with New Testaments and Bibles from printers and publishers far and wide and a genuine Luther Bible needed distinguishing from pirated versions.

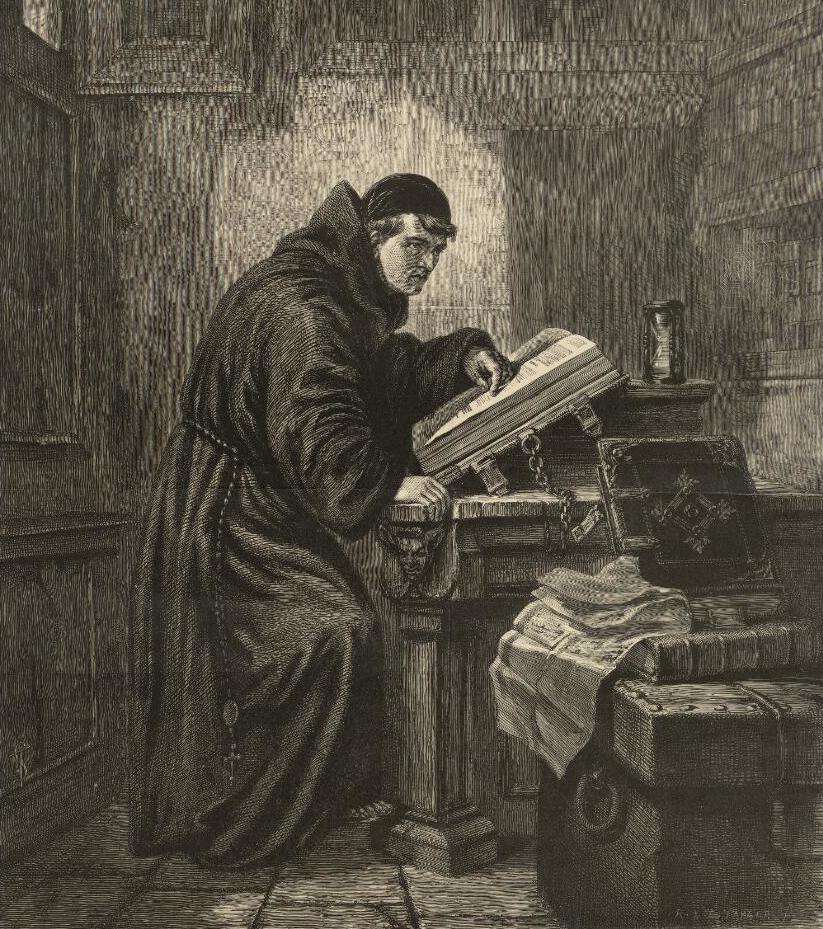

Luther’s 1522 September Testament launched the project of democratising access to Scripture for German-speaking people. From being read in a scholar’s study, a monk’s cell or a nobleman’s chamber, and usually in Latin, it would now enter the homes of educated citizens who could afford a copy, to be read aloud in German to the household. Before Luther, there had been 14 Bibles in High and four in Low German, none of them fully satisfactory. Now, here was a New Testament in contemporary German, reflecting both the language and discourse of public service in Saxony, and German as spoken in the street. In early 1522 Luther binge-translated a first draft in just 11 weeks, while sequestered in a castle and protected from a rising tide of opposition to his reforming activity in both Empire and church.

Luther worked from the latest and best Greek New Testament edition available, by Erasmus, with the Latin Vulgate used throughout the Western church also in his memory and on his desk. Back in Wittenberg, with his team of collaborators, months of revising and reworking the text for publication would follow. From this beginning came an enterprise that would keep Luther and his associates busy for the next 25 years, until his death in 1546: a steady supply of ever-improving New Testaments and Bibles, in High or Low German, came from Wittenberg, with all profits reinvested in a sustained publishing drive that the September Testament had launched.

Why all this effort? For Luther, the state of the church and the salvation of ordinary people were at stake. In his Freedom of a Christian (1520), Luther had spelt out how fundamental, for human lives, was the Word of God, with the gospel of Jesus Christ at its heart. To come to saving faith in Christ, or to come to love and serve Christ more, people needed to hear it – in their heart language. In church, this was not happening. Change was needed.

Luther’s September Testament targeted people’s understanding. His main concern was how his translation sounded. In the early-16th century, books were heard while read aloud since relatively few people could read, or read well. Luther wanted the words of the evangelists or apostles in the cadences and rhythms of everyday speech, so that they would roll off the reader’s tongue, appeal to listeners’ ears, lodge in their memory and provoke or sustain faith in Christ.

The text had no verse numbers and little punctuation. Instead, to facilitate reading aloud, and to help the reader scan the sense or pause for breath, slashes divided each paragraph of every chapter into units. To help readers interpret what they read at their kitchen table, important aids were built-in: a general preface, introducing the whole New Testament to readers, and other prefaces to most individual books; and throughout the text, context-sensitive marginal notes on significant or difficult passages. From the start, Luther Bibles would be study Bibles. Reading the book of Revelation presented a particular challenge. During the Middle Ages, Revelation had been extensively illustrated as an aid to interpretation for private devotion or for study in monasteries. Uniquely for Revelation, Luther therefore chose to target not just listeners but viewers. Instead of marginal notes, he provided 22 full-page visual aids: interpretative woodcut illustrations by the celebrated artist and now publisher, Lucas Cranach the elder. Within weeks, the potency of these images would also bring the September Testament notoriety, since several depicted a papal tiara, in conjunction with Revelation’s monsters or Babylonian harlot. The cartoons caught the public imagination and created further ecclesiastical and political waves, with Luther temporarily agreeing to substitute toned-down images for the December reprint.

By a ripple effect, translations in other languages, including English, swiftly followed Luther’s New Testament. For undertaking the illegal and dangerous work of translating the New Testament into English, William Tyndale was in continental exile and visited Luther in Wittenberg in 1524. Tyndale’s 1525–26 New Testament shows a striking debt to Luther’s German that later English translations would also display: a revision of Tyndale in light of the latest scholarship would be the basis for the Geneva New Testament (1557) that mirrored Luther’s emphasis on the spoken Word, while the full Geneva Bible (1560) would further develop helps for interpretation.

Luther’s theological writings, or the ideas they expressed, are well known. Somewhat overlooked, by comparison, is just how influential Luther was in placing the Bible in the hands of ordinary people and thereby spreading the gospel or reforming church and society, not merely in the German-speaking area but throughout Europe, with the effects of Luther’s extraordinary Bible work still felt today. So rich a legacy deserves to be commemorated and explored. This September’s quincentennial of his September Testament offers a suitable occasion for marking the event and reflecting on some of its many ramifications.

Five hundred years on, this September, Union Theological College will host and organise an international conference: ‘Martin Luther. Bible translator, illustrator and publisher. 500 years’, as a team of scholars gathers in Belfast to investigate and assess Luther’s achievements and heritage. Each conference session aims to make cutting-edge research accessible, with contributors tackling key aspects through presentations, conversation and Q&As: Luther’s own contribution and its wider European impacts, notably on the English New Testament and Bible; past and present implications for Bible translation more generally; and theological implications from all this for public life and discourse. This is an in-person conference, but all conference sessions will be accessible live online and for a limited time afterwards for those unable to attend in person.

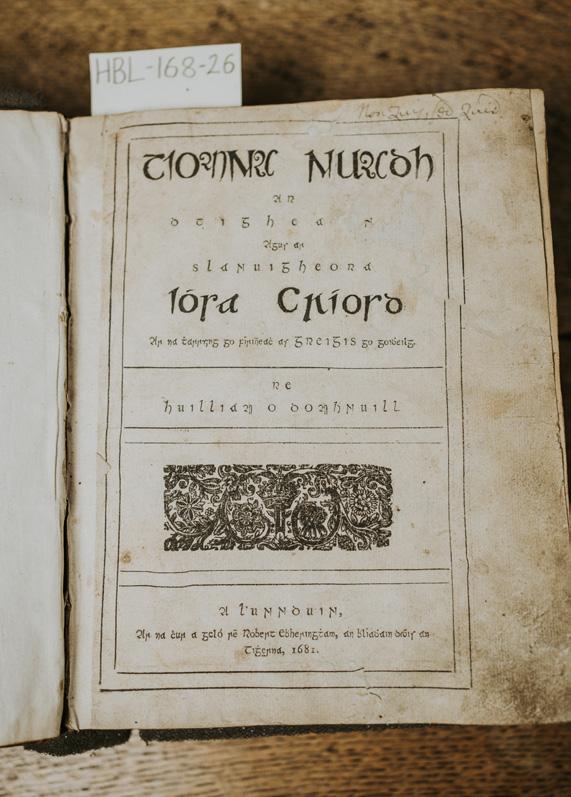

A series of digital exhibitions, curated by the librarian of the College’s Gamble Library, Joy Conkey, has been rolled out progressively since January and may be accessed on the College website. Each digital exhibition showcases Bibles or related items from the Gamble Library’s special collections. The first introduces Luther’s Bible work. Another takes the early English Bible as its focus, particularly the largely forgotten Geneva Bible that was English-language Presbyterianism’s Bible for over 80 years. Other digital exhibitions are devoted to the King James Bible, the Bible in Gaelic or in Scots or resources that explain the Bible.

To coincide with the conference, the Gamble Library’s new exhibition facilities will also host a physical exhibition. Visitors to the College during the two days of the conference can look forward to discovering Bibles and related works of special significance, whether from the collections or on loan from other libraries, and take home a souvenir guide. The exhibition will remain open for individuals or groups to book a visit during the autumn.

Conference-goers will also be able to engage with contemporary Bible translation, distribution and promotion through exposure to the ongoing work of three partner agencies: Bible Society for Northern Ireland, Biblica and Wycliffe Bible Translators. During the conference, together they will present their work in translating the Bible and its impact on people, with opportunities for visitors to get involved.

Professor Gordon Campbell is principal of Union Theological College.