4 minute read

Rochester’s Lost Baseball Stadium

The “new ballpark on Fourth Street” sat 1,250 people. And lasted four seasons (1928-’31).

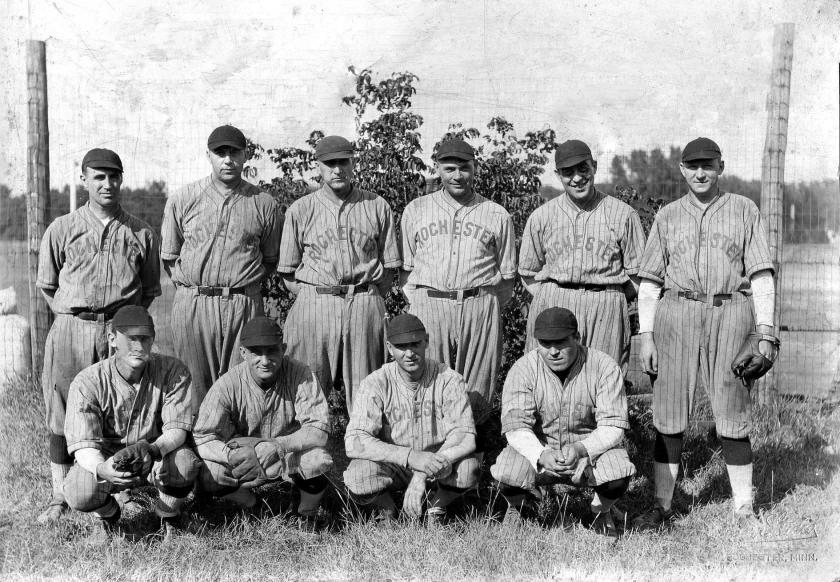

by Thomas Weber photos courtesy History Center of Olmsted County

The first pitch at Rochester’s new ballpark sailed way over the catcher’s head. That should have made everyone in attendance happy that Dr. Charles H. Mayo, who threw the ball, had become a surgeon rather than a ballplayer. It was the afternoon of June 3, 1928, and Dr. Charlie had the honor of throwing the first pitch at the park before the opening game between the Rochester Aces—the city’s semi-pro baseball team during the 1920s—and La Crosse. An estimated 1,500 people were on hand to witness the festivities, which included a parade to the park, marching band, and Dr. Charlie’s toss over the head of Rochester Mayor Fred Haase. After that, the real athletes took the field, engaging in a slugfest that saw the Aces, led by player-manager Claude McQuillan (who also owned the new stadium) get beat by a score of 10 to 7.

The new park was located at Fourth Street and Fourth Avenue Southeast, where the Holiday store now stands. It was intended to replace the former baseball diamond at Mayo Field.

Rochester’s baseball and football teams, including those of Rochester High School, had played their games at Mayo Field for years. Apparently, though, there was a common desire to find a new site for sports.

In the late 1920s, as talk about a new ballpark gained steam and support, the city park department dismantled the bleachers at Mayo Field. “It is expected that the field never again will be used for baseball purposes,” the Post-Bulletin reported in March 1928. Thus, it became imperative, if Rochester was to host baseball games, that the new park become a reality as soon as possible. McQuillan that spring revealed plans for an L-shaped 1,350-seat grandstand, bleacher seating for another 200 fans, an oblong running track surrounding the ballfield, and adjacent parking. “The seats will have back rests, unlike the uncomfortable benches in the old Mayo Field stands,” the PostBulletin reported.

McQuillan planned to sell 100 shares of stock at $100 each to help finance the new field.

“He believes that baseball can be made to pay and that his scheme of financing the game will be entirely successful,” the Post-Bulletin reported.

McQuillan talked of the stadium as a civic enterprise, and said he would offer use of the stadium for football games, track and field events, and even circuses and boxing matches.

As the opening day approached, the field and grandstand were still under construction. The area had been a swampy plot of land adjacent to Bear Creek, and required some effort to be formed into a playable ballfield.

To push the work over the finish line, McQuillan requested—and received—financial help from the Commercial Club, which promised to raise $6,000.

“McQuillan deserves ample credit for promoting the ballpark to this point,” said Roy Watson, president of the Kahler Corporation.

“Baseball is necessary to the city of Rochester,” said John Madden, owner of the Martin Hotel, who chipped in $100. Donations from other hoteliers, restaurant owners, and retailers raised $3,000 within a week.

Soon, everything was in place for the grand opening of Rochester’s new sports palace.

On the day of the game, Mayor Haase “was out early in the morning for the final try-out, with all the boys in the neighborhood throwing at him,” the Post-Bulletin reported. The mayor vowed to catch Dr. Charlie’s best fastball.

The doctor, meanwhile, “would not admit that he has ever pitched a game,” the Post-Bulletin said. But when Dr.

Charlie took the mound, the newspaper reported, his “agility in the windup and lunge toward the plate showed that he has been on the sandlots before.”

If only his pitch had been placed where Haase could reach it.

As for the ballpark itself, “the field was a revelation to hundreds who remember the area as a marsh,” according to the Post-Bulletin. The stadium was officially inaugurated, and as is so often the case with a new baseball season, it was a time of promise.

Over the next couple of years, the “new ballpark on Fourth Street,” as it was frequently referred to, seemed ready to deliver on that promise, hosting sports of all sorts.

In June 1930, “Know Rochester” magazine informed visitors to the city that if they wished to watch a ballgame, “the ballpark is in easy walking distance from the main part of town, four blocks east of Broadway on Fourth Street Southeast.”

Already that summer, though, the ballpark was facing financial difficulties. At one point, F.W. Oesterreich, who was promoting nighttime baseball in the city, expressed an interest in buying the park.

Still, the stadium was a busy place. That September, the Rochester Aces football team opened its season by hosting a team from Spring Valley at the ballpark. In August 1931, a boxing card was presented at the park in conjunction with the state American Legion convention.

That year, though, marked the final full season of the “new ballpark.” Despite McQuillan’s best plans, there appeared to be no long-term financial viability in a privately owned stadium—at least not in Rochester.

In 1932, according to schedules printed in “Know Rochester,” baseball games had been returned to Mayo Field, and the Rochester Aces football team was playing home games at Mayo Field and at Soldiers Field. Both Rochester High School and Rochester Junior College were also playing football at Soldiers Field.

Despite everyone’s best intentions, it had been a short season for the new ballpark.

By 1940, Tauer’s Supermarket and the Southern Minnesota Supply Company had taken over the site of the ballfield. As for McQuillan, he went on to be elected mayor of Rochester four times in the 1940s and 1950s. He died in office in 1957.

Years ago the Post Bulletin was formed (Rochester’s two newspapers-—The Post and Record and The Rochester Daily Bulletin-— merged in 1925).

7

Days a week the Post Bulletin publishes its flip-through E-edition (an online version that looks like the actual newspaper).

That’s 68,493 pageviews per day.

19

Number of other news publications across the Upper Midwest-—including the Duluth News Tribune, Brainerd Dispatch, and Bemidji Pioneer—you can access for free with your Post Bulletin

Number of full-time local employees who work on the news side.

3 OUT OF THE PAST 6

Number of years the Post Bulletin has won the Vance Trophy, presented to the Best Newspaper in Minnesota by the Minnesota Newspaper Assoc.