3 minute read

Neither HERE Nor THERE The Indipino People of Bainbridge Island

Gina Corpuz grew up with deep roots in the Bainbridge Island Filipino community. Her father Anacleto was a raspberry farmer who helped found the Filipino Growers Association in 1935 and invested in the down payment to purchase the Filipino American Community Hall, now a national historic site. She knew very little, however, about her mother’s history. Evelyn Williams left when Corpuz was 5 and her mom’s side of the family was rarely discussed.

As an adult, Corpuz became curious and dug into her mother’s background. She discovered a story steeped in both tragedy and resilience. Williams was born into the Squamish tribe of British Columbia, but as a young child was taken from her family and placed in the St. Paul's Indian Residential School in North Vancouver. The school was one of 140 set up by the Canadian government to assimilate Indigenous children into mainstream Canadian society. Between 1831 and 1998, approximately 150,000 children were forced to attend these schools, run primarily by the Catholic and Anglican churches, where they were provided little formal education, suffered abuse and were stripped of their native languages and culture.

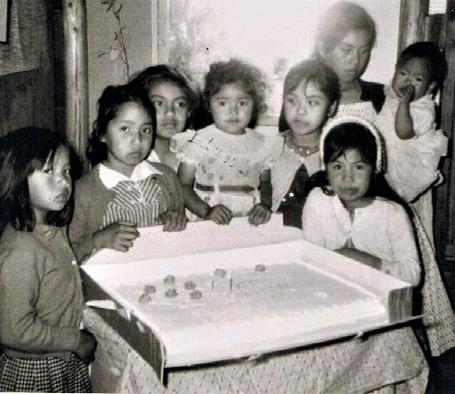

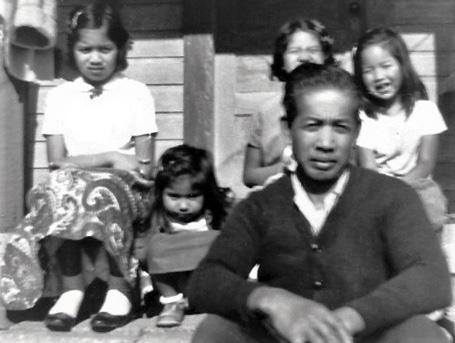

After leaving school in the early 1940s, Corpuz’s mother was one of 35 Indigenous women from 19 different tribes in Canada, Washington State and Alaska who came to Bainbridge seeking a better life. They found employment as laborers, picking strawberries on the island’s booming berry farms. Many of these women, including Williams, fell in love with and married the Filipino immigrants who worked alongside them in the fields. Their unions resulted in over 150 mixed-race offspring.

These children were raised in an environment in which their native lineage was largely erased. “We didn't even know we were Indigenous children.” said Corpuz. “Our fathers were founders of the Filipino American Community, but in the Filipino Hall we never recognized any of the cultural traditions of our Indigenous mothers.”

Corpuz now takes pride in and speaks out on behalf of her people, who identify themselves as Indipinos. She is executive producer of the award-winning documentary, “Honor Thy Mother: The Untold Story of Aboriginal Women and their Indipino Children” and co-founder of the non-profit Indipino Community of Bainbridge Island and Vicinity.

She believes there is room to celebrate both sides of her family. “For me, there's no law that says you can only be devoted or committed to one community.” she said, “I don't have to say that I'm 50 percent Filipino and 50 percent Indigenous. I can be

100 percent Filipino and 100 percent Squamish.” She hopes that a greater understanding of their rich and complex heritage will allow future Indipino generations to both cherish their ancestry and to support other oppressed communities. “We need to stand beside one another in order to combat racism, discrimination, and prejudice,” she said. “I hope that in the future, my grandchildren will have both the skills and the knowledge to be advocates for social justice and to protect the rights and privileges of all people.”

For more information, visit indipinocommunityofbainbridge.org.

Our Community is an ongoing collaboration with the Bainbridge Island Historical Museum. This series, in conjunction with the Our Community: Past to Present exhibit, scheduled to open at BIHM in Spring 2022, will explore the diverse voices that make up our island in this and coming issues.