7 minute read

DURWARD: BROTHER

Brotherhood is an easy word to throw around in fraternity, but a harder one to live. It’s more than a shared badge, creed or handshake. At its core, brotherhood is about relationships; deep, genuine and enduring ones. It’s being known, being counted on and being loved, not for your accomplishments or your titles, but for who you are. It’s remembering a birthday, knowing when to call someone on the phone and showing up when it matters most.

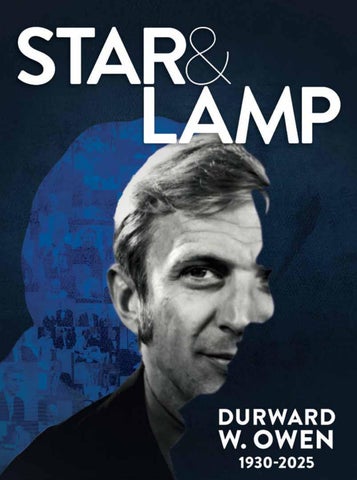

Before he was Pi Kappa Phi’s chief executive officer, before he was Mr. Pi Kappa Phi and before he was synonymous with the word fraternity, Durward Owen was simply a brother.

Durward joined Pi Kappa Phi at Roanoke College looking for the bond of brotherhood, but in the end, he was the one who taught the rest of the Fraternity what brotherhood, at its very best, could be.

He didn’t do that with grand speeches or proclamations preaching about the meaning of brotherhood; he did it in the way he lived his life.

“Durward anchored his life in loyalty,” said Joe Brady, Epsilon Omicron (Villanova). “And he lived it every day.”

Durward didn’t just know a lot of people; he built relationships, and then treated them like they mattered, because they did. “Relationships were his priority,” said

Chief Executive Officer Jake Henderson, Beta Theta (Arizona). “That’s how he built the Fraternity: one personal connection at a time.”

Each one of those many connections, and there were hundreds, was intentional. They weren’t driven by obligation or agenda; they came from a place of care. “He was about as good a friend as anybody could have,” said Phil Tappy, Lambda (Georgia). “He cared about everybody that he ran into, and he put in the work to stay in touch. That’s something a lot of people don’t do, but he did it because he cared.”

That’s how he built the Fraternity: one personal connection at a time.

To know Durward was to feel like family. Glenn Aspinwall, Gamma Kappa (Georgia Southern), remembered the way he and his fellow leadership consultants would be greeted at the Owen home: “When we’d come visit, he’d say to Connie, ‘One of your children are here.’” Being close enough to be treated like family meant being expected to act like family, too. Glenn once made the mistake of knocking on the front door, despite always having gone to the back door before. When he

opened it, Durward asked “Who are you?” with a serious, straight face. Confused, Glenn started to answer until Durward finally broke into a grin and said, “Well, friends don’t come to the front door.”

Other staff members shared that sentiment, and the bond Durward cultivated among his employees. “We were experiencing an entirely new chapter of Pi Kappa Phi,” said Stuart Hicks, Kappa (UNC-Chapel Hill). “We were from a whole lot of different chapters, but he made staff feel like a chapter in itself, and he gave us those bonds of brotherhood unlike any other.”

Even through disagreements and differences in ideology, he found common ground and formed lasting relationships. Phil and Durward first interacted with one another when Phil was an undergraduate who had just taken over as his chapter’s historian and created a newsletter filled with party stories and toga pictures. It did not meet Durward’s expectations, so he called Phil up and told him. “Nobody likes criticism,” said Phil, “And I was working harder in my chapter than anybody, but after a while I realized he was right. I thought, if I were an alumnus, is this what I would be proud to see? He was right. He usually was.” That was the start of an unlikely friendship. When Phil first moved to Charlotte, Durward introduced him to everyone in town, invited him to join his Rotary club and took him under his wing,

What is fraternity? In one word, fraternity would have to be defined as people. For, like so many things in life, without people, you have nothing.

(continued from page 26) giving him community in an unfamiliar place. “We didn’t always see eye to eye on things,” said Phil. “In fact, there were many things we completely disagreed on, but we always got along anyways. We went to breakfast together for years. We were breakfast buddies for a long, long time.”

That kind of bond is rare in life, but it was typical for Durward.

He had a way of showing up for people in both their big, public moments, and in the small, less noticeable ones. “Durward and Connie were very kind to my wife Lisa and me when we were house hunting in Charlotte,” Phil recalled. “We spent the night at their place, and I’ll never forget it. Lisa wasn’t feeling great that morning, and Connie looked at her and said, ‘Lisa, you’re pregnant.’ Unbeknownst to us, she was. Durward always loved that story and being part of that moment.”

At times, Durward’s love came through laughter. Ed Bennett, Xi (Roanoke), remembered a moment from his early days of fatherhood: “Durward and Connie drove over to my house. This was the first time we were leaving our baby daughter with a sitter, and Durward says to the sitter, ‘Just give her a dirty sock and set her in the closet and she’ll be fine.’ Still today, I think of Durward as one of my very best friends.”

He loved people enough to joke with them, to lighten the weight of life, and remind others that, even in the chaos, joy was essential. And then, there were his hugs.

“When Durward hugged you, it was a real hug,” said J. Ernest Johnson, Alpha Iota (Auburn). “It wasn’t some ‘bro’ hug or side hug. You always felt like, man, this guy’s glad to see me.”

Sometimes, that affection surprised people. “I was leaving for Atlanta as a consultant,” said Wally Wahlfeldt, Upsilon (Illinois-Urbana-Champaign). “Durward went to give me a hug, and I kind of stiffened up. I didn’t hug men. And he goes, ‘It’s all right to give another man a hug, you know.’ And he made me give him a hug.” Wally never forgot it. “I make a point to hug my friends all the time now.”

“Even if later, we are occupied with important things, even if we fall into misfortune, still let us remember how good it was here once, where we were all together, united by a good and kind feeling which made us, perhaps a little better than we were.”

Unapologetically, the way Durward showed his care gave others the permission to care, to be present and to love out loud. To fully live brotherhood.

Durward had a gift for keeping that trust alive and building connections into what would otherwise be everyday moments. “We always had memorable ski trips,” recalled Kelly Bergstrom, Alpha Omicron (Iowa State). “You’re staying in the same building for a week, and you really get to know people. That was another genius of Durward, getting people together in that kind of setting. It kept you interested in doing things for the Fraternity.”

He knew that what kept people coming back and serving the Fraternity were the unplanned moments, the laughter around the dinner table and the long talks after days spent bonding.

“Everything I do for the Fraternity is because I owe it to him,” said Wally. “He inspired so many of us to serve on boards, write the checks and just show up for Pi Kappa Phi.”

Through intentional relationships, Durward created a culture where men could show up for not just the Fraternity, but each other. He inspired them to stay in touch, give real hugs and call each other without needing a reason.