22 minute read

Reflections on seven crucifixes various

from PV Journal Munich

by Pietre Vive

#1 El Cristo de Burgos

40 This is the Crucifix of “El Cristo de Burgos”, “Christ of Burgos”, which is inside the Cathedral of the city. It is a fourteenth century carving, made of wood, but covered by leather to give off a sense of realism, which especially comes through in the rendering of the wounds which are painted on the skin. Christ’s head, arms, legs and also fingers can be moved, as it is used in a kind of public “performance”, a re-enactment of the crucifixion, the descent from the Cross and even the burial of our Lord, every Good Friday.

Advertisement

It was first placed in an Augustinian convent next to the city, where it received a huge devotion from people, and became quite famous; in fact, its veneration spread out all over Spain, South America and the Philippines. There is also a chapel dedicated to it in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. St Teresa of Jesus prayed in front of this Crucifix when she arrived in Burgos, as well. Nowadays it is placed in the Cathedral in a chapel that takes after its name: “Capilla del Cristo”, “Chapel of the Christ”. There, the Holy Mass is celebrated every day, and is opened for personal prayer and for the sacrament of the reconciliation.

The huge devotion of the Crucifix which it garnered over time incites a lot of curiosity and wonder. What is it about this image of our Lord on the Cross that has touched so many souls? In truth, these kind of images with realistic appearances, hair and clothing, are not very common in the north of Spain and, usually, they are not greatly appreciated in this area. But perhaps, on pausing for a moment to reflect upon it, as a piece of religious art, it could also have a message for each and every one of us.

St Teresa praying before this image comes to mind. Her own path of holiness was related to the humanity of Christ and the Ecce Homo. The Christ of Burgos is indeed a very realistic carving, with a lot of wounds and injuries, suffering on the Cross, to the point of death. Perhaps it is precisely this suffering that connects so many people along so many years. The one who stands in front of this Crucifix may immediately recognise the suffering of this crucified man. And He suffered a lot, He suffered to death. We all carry much pain, and so can be understood by God, because Jesus was in great pain as he hanged from the cross. And not only can we be understood by God in our afflictions, but also we can connect to Him, once again through our Lord Jesus Christ. Staring at the Christ of Burgos, at His mistreated Body, therefore helps the viewer to enter into communion with God through His suffering on the Cross.

There is something striking in Christ’s face too. In spite of being on the brink of death, and with such a damaged body, the face imparts a sense of calm, not quite smiling but almost; in peace. In the most terrible suffering, our Lord seems to be calmed. It is as if though Jesus was suffering in His Body and Soul, and yet there was something upholding it all. This is the experience of the Christian sense of suffering. It is very difficult to explain, but surely, every living person has some experience of this reality. When a terrible suffering befalls our life, with the grace of God, it can be mysteriously affronted supported by a layer of faith and strength, which does not eliminate pain but allows us to walk ahead. Staring at the Christ of Burgos, at His expression of serenity, is thus also a reminder that suffering can be lived in a mysterious but meaningful way, thanks to faith.

This crucifix of “El Cristo de Burgos” can help us to join our Lord in the suffering of the Cross and to realise that, ultimately, we are not alone in our pain and suffering, but are held up by God.

#2 The “KorNis crucifix” Cluj/Kolozsvár/Klausenburg, Romania

This is an eighteenth-century copy of a sixteenth-century crucifix, located in a chapel of the Franciscan church in Cluj, Romania. The original was produced in a Transylvanian workshop, and is located in a Franciscan church, the so-called Alserkirche, in Vienna.

The copy from Cluj was made in 1713, at the request of count Kornis Zsigmont, the then governor of Transylvania and one of the most influential Catholic personalities of his time. The crucifix was first located in one of his mansions (Mănăstirea/ Szentbenedek), and in 1731 was donated to the Franciscan church in Cluj and placed in the Holy Cross chapel, which also shelters the graves of the Kornis family. Soon after, the crucifix became the centre of quite a popular local cult.

Jesus is represented here in the so-called “heroic type”, with a powerful musculature, looking rather like an athlete, and as such very human. Also, if we were to focus on the hands, we would notice that they are clenched, as if he were in a fight, in a struggle. And he actually is in a fight. This is the final battle between the incarnate Word of God and the ultimate enemy: death. Here, death is visually represented by the cross, and Jesus is fighting and struggling against it.

Lord Jesus, you who experienced our suffering and our fears, in your final struggle you conquered death. Since then we know that evil does not have the last word over your creation.

Please grant us your strength and your resilience in our daily struggles against indifference, against hate, against discrimination, which all represent the death of our souls.

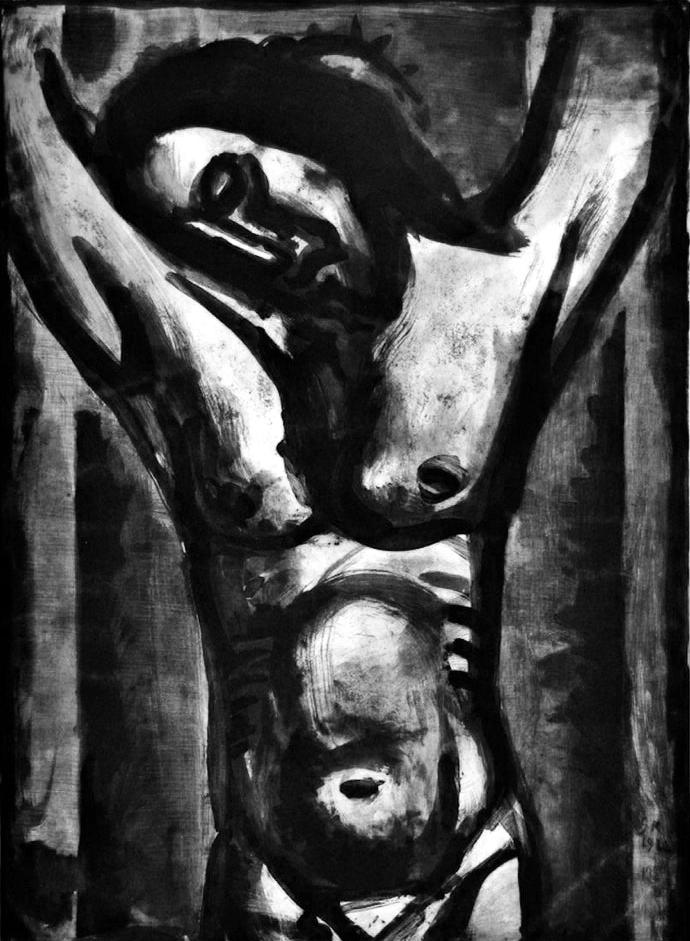

#3 Jesus sera en agonie jusqu’a la fin du monde (Jesus will be in agony until the end of the world) from Georges Rouault’s “miserere”

This image could be a stained-glass window with the light shining through, a photo edited in black and white, or even a painting. However, it is a replica of a print using India ink on a copper plate in rotogravure. The artist is Georges Rouault, a French Christian artist who made his mark in the beginning of the twentieth century. This print is part of a series of fifty-eight prints, considered as one extensive artwork called Miserere. The Miserere prints are displayed in the church of St Séverin in Paris where we usually have our services.

In Miserere, the artist shows the suffering of the human being, his sins, his faults, and his hopes. The figure of Christ is illustrated in four out of the fifty-eight prints, including the one we see here, which represents the crucified Christ. It reflects the strength and the heart of the Miserere series: the passion of Christ meets the passion of humanity. Christ is not in heaven. He is on the cross as soon as suffering strikes every man and every woman. The text accompanying the image says: Jesus will be in agony until the end of the world.

This print shows Christ’s ultimate fragility; he is nailed, his arms up high. We do not see the full length of his arms, nor do we see his hands or legs. It seems that they are not needed anymore, that the essential is elsewhere now. The “INRI” inscription is not visible either nor is the wood of the cross. Behind the figure of Christ is a neutral background, without showing any specific landscape; the crucifixion cannot be limited to any place or time. What is left is the crown of thorns, discreet and seemingly falling down. It is the only attribute reminding us that this figure is the Son of God.

All our attention is put on the bust, and especially on his face that is in terrible agony. It is deformed by signs of pain and sorrow, as if he had been crying but without tears. The misery is profound, like a screaming lamentation, yet in complete silence—a speechless cry to his Father. His son is there, almost dead. Our Lord gives Himself here, on this cross, on this place where He will always accept His Father’s will until the very end; dying with these chains—suffering and death—in order to dwell in them, to overcome them and to finally liberate us from them.

He is also nailed naked, without clothing, without protection preserving what is most intimate, making him even more vulnerable. Jesus is exposed naked on the cross, experiencing the violence of being seen by all, in such inequitable conditions compared to the clothed spectator.

It is because he is naked and because he has lost everything that makes him unique; the crucified Christ carries all the crucifixions of our humanity. He carries our own crucifixions when we are confronted with the absurdity of suffering in its various forms: sickness, violence, mockery, manipulation, physical and sexual abuse, death.

Nevertheless, the most fascinating is the white in the image, the light that shines. It gives this artwork all of its meaning. It testifies to the prowess of the artist, who, through his engraving technique, has to remove matter to create a void, spaces that are not printed and therefore remain white. Digging deeper into the print, bringing out the light. This gesture can inspire us to empty ourselves to let this light shine through. Therefore, it changes our perception of Jesus’ tortured body. Being in pain, this same body already shows the signs of resurrection. It is the great mystery that, although we do not fully comprehend it, we may nonetheless accept and live with Christ.

In its own way, this work reveals to us what the crucifixion of Christ, and every crucifixion we go through in our lives, can be: it is not an explanation for our suffering, nor is it a response. It is a sign of faith. We are not alone in the darkness of our sufferings; Christ is with us in this darkness and brings his light to it.

Almudena Mounier-Tebas (& LS paris)

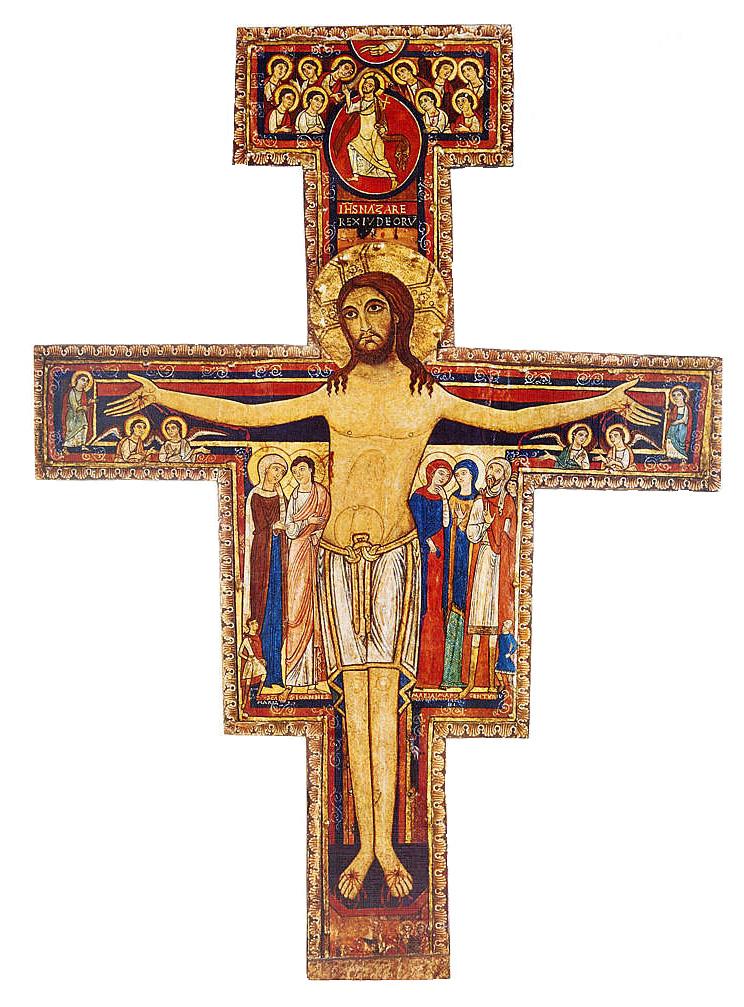

#4 il crocIFIsso di san damiano basilica of St clare, assisi, italy

At the beginning of the month of March, the Basilica of St Clare (where the crucifix of San Damiano is located) was the first church in Assisi to close its door. Some days before we took a picture of the crucifix, in which we can see the shadow of the crucifix resembling a pair of big hands.

Thousands of people are familiar with the life of St Francis. He was the son of a rich merchant of Assisi and wanted to become a knight in order to gain glory and honour, but something radically changed the course of his life. This change happened in the church dedicated to San Damiano.

San Damiano is a beautiful and peacefull place outside the walls of Assisi. At the time of St Francis, the church was already falling into ruins, so, it is at least a thousand years old and there were buildings here for many centuries before that. The name of the church originates from the plague saints Cosmos and Damian, popularly venerated in the area.

After St Francis’ possibility to became a knight fighting in a terrible struggle between Assisi and Perugia, in the year 1205, a lot of things in the life of the young man rapidly changed. He understood that his life was not to become a knight and nor was he to become a rich merchant as his father. Francis was in trouble. He didn’t know what he really wanted and what he had to do. One day he entered in the ruins of the ancient and abandoned edifice of the church of San Damiano, and saw the crucifix (which in truth is an icon). As he stood before the crucifix, he prayed: “Most High glorious God, illuminate the shadows of my heart. Lord, give me right faith, sure hope and perfect love, good sense and understanding so that I may always follow your holy and true commandments”. To his great surprise Jesus replied to him saying: “Go Francis and repair my house, which, as you can see, is falling into ruin”.

He first concentrated on repairing the church buildings of San Damiano and nearby churches. But his great “repair” to the Church was the founding of the Franciscan Order.

In one of the most difficult moments of his life Francis looked for something that could help him but ended up finding much more. He met somebody who really loved him!

An unknown Umbrian artist painted the original crucifix in the twelfth century and it is strikingly iconographic in character; for this many identify the artist as a Syrian monk, since it was known that Syrian monks were present in the area at that time. In 1257, the Poor Clares left San Damiano, taking the crucifix with them. It is for this reason that we find the original crucifix in the Basilica of St Clare.

This iconographic Crucifix does not express the horror of death by crucifixion, but the nobility of eternal life. The most striking element of the San Damiano Crucifix is the figure of Christ as a source of life, radiating the hope of the Resurrection. Christ looks directly at us with a compassionate gaze, triumphant and regal. He seems to support the cross, standing in His full stature. His hands spread out serenely in an attitude of both supplication and blessing, which the iconographer has further emphasised through Jesus’ tranquil and gentle expression.

Jesus spoke to St Francis more then eighthundred years ago, but he “speaks” to us even today. After reflecting on the prayer of the young Francis and the meaning he could have at that precise moment in his life, it might be illuminating for us too, to contemplate what meaning it may have to pray with the same words of St Francis in this difficult time that we are all living.

“In your hands, Lord, I entrust my life.” We can express all our gratitude for the gifts we receive from Him and ask him to imprint this mystery of love in our heart, so that we may become a living experience of His love.

In 1205, St Francis opened his heart to God’s love. We can do the same: to open our heart to God’s amazing grace. We have a lot of dreams and projects that had to be cancelled, postponed, reconsidered or even, radically changed. This is the moment to deeply understand ourselves, to think seriously what we are doing in our life, which is a gift. Some hours before his death, Francis said to his brethren, “I have lived my life. God will show you how to live your life”... in joy.

raffaella & sara (LS assisi)

#5 the crucifix in the “garden” church of san giovanni battista, matera

The Crucifix in the church of San Giovanni Battista in Matera, Italy, was made between the end of the sixteenth and the beginning of the seventeenth century. The artist is not known, although probably originating from Matera or, at least, from the South of Italy. This crucifix has experienced a sort of pilgrimage before finding its place in its current location as it was in fact commissioned for the church of St Augustine in Matera, where it hung until the beginning of the twentieth century.

However, the parish church of San Pietro Barisano, suffered several architectural problems that made it necessary to move the parish to that of St Augustine, with its own crucifix. Because of this, the crucifix experienced its first displacement and it was brought to a different rock church called Madonna dei Derelitti. After just a century, this church started to fall into a derelict state due to the effects of the weather and lack of care, so it was necessary to once again move the crucifix to a wellprotected place. It was the second displacement of the crucifix. The third displacement was the one that brought the crucifix to its final location, at the church of San Giovanni Battista, in 2018.

The crucifix the builders rejected has become the cornerstone of this church and of the people of Matera.

Within its new location, the crucifix gained new meaning. Therefore, we must first also understand the main theme of the church. Observing the columns closely, and more carefully at the capitals, one will notice several decorations of vegetable, fruits and flowers. This same kind of decoration may be observed in the main apse of the church, behind the crucifix. The main theme is then that of the Garden, a holy Garden. The whole church is built as if it were a delicious and gorgeous garden, the place in which you can stay with the Creator, who created Man. Such a garden reminds us almost immediately of the Garden of Eden, the Heaven of Earth. There, Man brought death to the Earth because they wanted to be like God; now here, with this crucifix, the son of God brings life to the Earth making himself a mortal man.

The forbidden fruit of Eden, so desirable, fascinating and captivating, which was stolen from the tree by humanity, here cannot be stolen anymore, since the new fruit is Christ himself, crucified in a new tree—the cross. His sacrifice is unconditional, totally free.

This kind of crucifix portrays what we call the Christus Patiens, the suffering Christ. Christ does not have a glorious expression or even a calm and serene look, like in other crucifixion typologies. Here, Christ suffers and therefore is not as beautiful as the forbidden fruit. In this way, this representation allows people to see the naked truth and think about themselves, about their own pain, while serving as a reminder that in their suffering they are not alone.

Moreover, in the perspective of the garden, we see that, with the grace of God, our sins become the place in which we can encounter Him. The wound produced by the fruit of sin is turned into the wounds of Christ, the fruit of the salvation, from which new life-giving blood flows for all those who are hungry and thirsty. In the same garden in which we lost ourselves, God can transform our sins into communion.

What, therefore, can we take from this crucifix? We can, perhaps, take a moment to focus on the physical wounds of Christ remembering those instances, those experiences in our lives in which we felt protected by them, in which we received the grace of God who turned our sins into communion with Him.

David Sarrocco (& LS Matera)

#6 the lord of poison Catedral Metropolitana de la Asunción de la Santísima Virgen María a los cielos, Mexico city

According with the legend, in the eighteenth century, there was a rich devoted man called Don Fermín, who went to mass very early in the morning every day. At the end of each mass, he would place a golden coin at the feet of a statue of Christ in the church, and finally he would kiss the feet of the image of Christ before leaving.

Don Ismael Treviño, was another rich man, but was also a very jealous man, who hated Don Fermín, and wanted to see him dead. He found a perfect way to murder Don Fermín, by poisoning, a poison that did not act quickly but invaded the body slowly and in a few days would have the expected effect. Don Ismael mixed the poison in a cake that was given to Don Fermín, who ate it oblivious to the danger he was in.

Don Fermín entered the Church as always, and when he finished and kissed the feet of Christ, a black stain spread over the whole figure, saving Don Fermín of the poison he had just ingested. When Don Ismael saw the scene, he regretted and confessed his crime. The noble knight looked at Don Ismael and was filled with compassion for him. He quietly forgave him and embraced him like a brother he had not seen in a long time.

Nowadays, this statue is the most revered in the Cathedral of Mexico City, especially by people seeking relief from their pain and illness.

This sculpture and its legend, reminds us that sin is a poison to the soul and that Christ, with his death and resurrection, has absorbed our sins. Christ cleanses us and protects us from sin, even when we are not aware of the danger, as long as we fully trust and live in communion with him. This allows man to lead a clean life, a baptised life, through the blood, death and resurrection of Christ.

I beg you, oh dear Lord, that the poison of sin no longer penetrate my heart; make it pure exercising all the works that are to your liking. It is what I ask you in honour of your admirable transfiguration, with what you greatly manifest in your infinite power.

#7 an early christian crucifixion basilica of santa sabina, rome

Scenes of the crucifixion are extremely hard to find in early Christian art. Indeed, this small wooden panel is the first known image of the crucified Christ with the two thieves that was intended for public display, yet dates from more than four hundred years after the Passion. It is not even displayed prominently, located as it is in the top left corner of the high wooden doors that mark the entrance of the basilica of St Sabina on the Aventine Hill, in Rome. This is all the more striking given the fact that the doors likely had a didactic purpose—to illustrate the doctrine of faith to catechumens waiting to be received in full communion with the Church. Why, then, was there such reticence in representing one of the central mysteries of the Creed?

In fact, our bewilderment would have bewildered early Christians. It is as if too much familiarity with the Crucifix has veiled our eyes, so that we are not shocked as we should be by the image of the Son of God dying in front of us the cruellest, most shameful death. Perhaps we could get closer to the horror it evoked, when capital punishment by crucifixion was still fresh in people’s memories, if for a moment we tried to imagine Him standing in front of a firing squad or sitting on an electric chair. If you feel this thought is unbearable— well, that is a perfectly sane reaction.

How did Christians manage to go beyond pure horror while thinking about the crucified Christ, and even dare to represent Him hanging from the Cross? Two important developments took place in the years before the panel of St Sabina appeared. The first was the abolition of crucifixion as a legal way of carrying out executions by Constantine the Great, in AD 337. The second was the process by which the Church gradually defeated heretics who could not accept the idea that Christ is at once fully God and fully man, yet one Person, forever. In AD 430–431, one of these heretics, Nestorius, was condemned by Pope Celestine I—the same pope who promoted the construction of the basilica of St Sabina.

A proper understanding of the two natures of Christ, united in one Person, allowed the unknown artist of St Sabina and his public to overcome horror with hope, and terror with trust. Being fully man, Christ dies. Being fully God, Christ cannot die. Being one Person, what is true of one of His natures is also true of His Person as a whole, thus he personally experiences death and personally experiences life everlasting. So, look—He is hanging from the Cross, a tomb looms in the background, but His eyes are wide open. Simply by carving this pair of open eyes, the artist of St Sabina manages to represent Christ as suffering and vanquishing death at once. And since the key to victory over death is prayer to the Father Almighty; look again— His arms are nailed to the wood, but also bent and lifted up in a prayerful posture. Crucifixion becomes the ultimate Lord’s prayer.

This has a further implication. If we learn how to pray like Him, we learn how to die like Him— surrendering our will to the Father so that we can look upon Him with our eyes wide open in Paradise. Looking at the figure of the thief standing at the left of the Lord, we feel that the thief learnt this lesson very well. He stretches out his arms, not just because he is forced to by the executioners, but because He wants to pray as the Lord does, to die as the Lord does, to enter the Kingdom as the Lord does. And indeed, he gets from the Lord what he asks for—just look at his smile.

Unfortunately, the facial expression of the other thief, the ‘bad’ one, is too worn out to be identifiable. Compared to Christ and the good thief, his arms seem much more rigid, as if his paralysis by sin lasted until he died. But if we take a step back and observe the whole group, we can notice it has a striking resemblance to the catacomb iconography of the three youths in the fiery furnace. And as the three youths prayed together and were saved together, perhaps, the artist dared to hope that even the wicked thief repented at last, bent his arms, and smiled in the glory of resurrection.

alessandro monti (LS rome i)