8 minute read

The Hidden World of Anesthesia

An Anesthesiology Resident Explains All

Written by Marianna Seefeldt and Rachel Torregiano

Advertisement

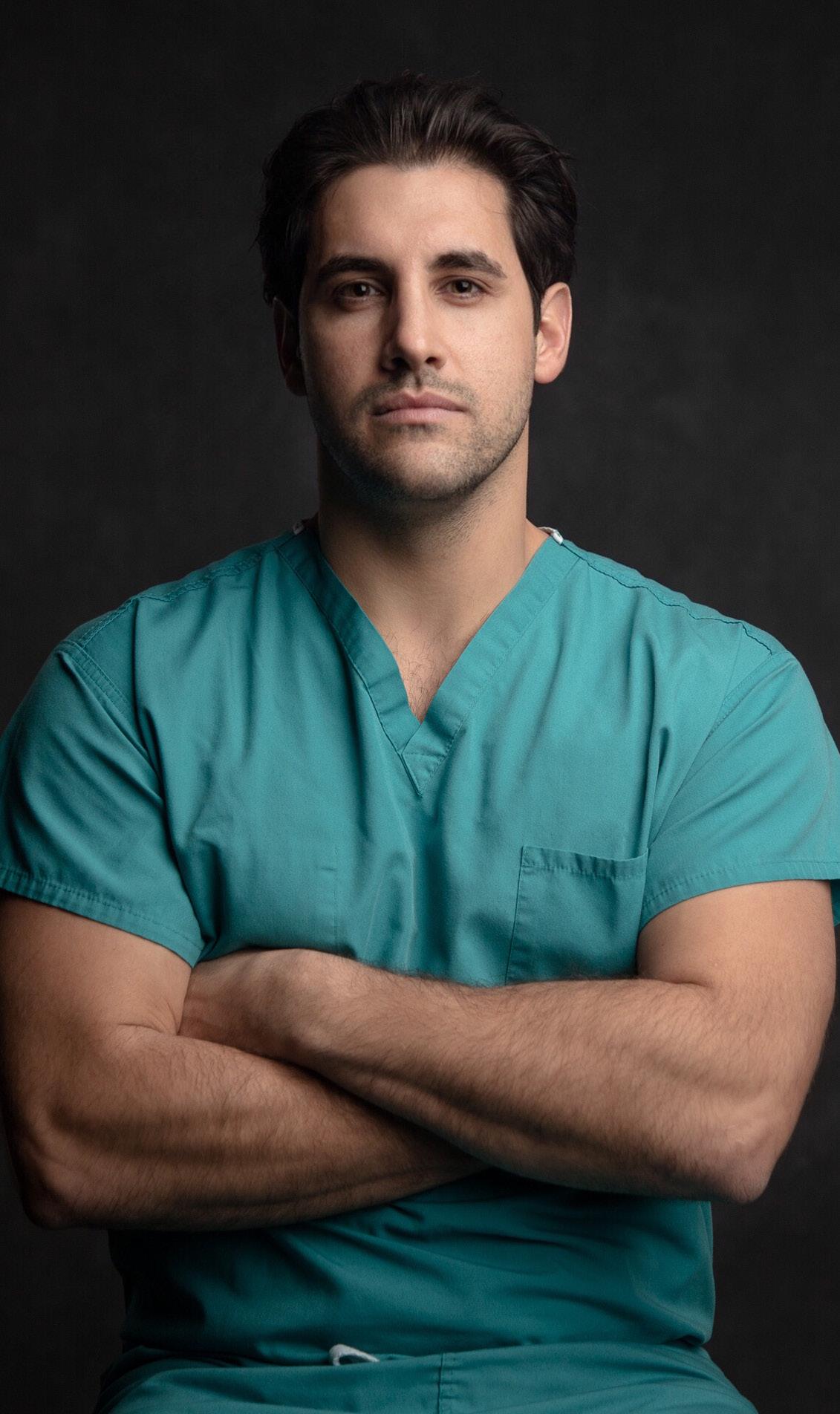

Dr. Nabil Othman is a fourthyear anesthesiology resident at Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, C.A., who recently finished writing his first book, Vigilance: An Anesthesiologist’s Notes on Thriving in Uncertainty. He’ll be graduating from residency at the end of June before beginning a fellowship year in Houston, TX.

Born in Chicago and raised in Michigan, a career in medicine piqued Dr. Nabil Othman’s interest at a young age. In middle school, Dr. Othman spent time helping his grandfather, who elected to manage his heart failure at home instead of pursuing invasive medical treatment. “He elected to have a nurse come to his house and help him during the day and I would help him out in the mornings, and I really enjoyed that,” said Othman.

After finding joy and performing well in his science classes throughout school, Dr. Othman applied to medical programs and soon began to pursue his MD from Wayne State University School of Medicine in Detroit. He first began his career in medicine with an interest in trauma surgery, but realized his third year of medical school it was not what he was looking for.

It wasn’t until his fourth year of medical school that everything clicked for Dr. Othman, when he spent a day with anesthesiologists. “I couldn’t do a formal anesthesiology rotation until after the residency application deadline because I decided late,” said Othman. Although it was risky, he was confident in his backup plan to work in an Intensive Care Unit or critical care if he didn’t end up liking anesthesiology. “Critical care and anesthesia are so similar that the odds of liking both are very high,” said Othman.

Now, in his last year of residency, anesthesiology has become both a career and passion for Dr. Othman. This is what drove him to write Vigilance: An Anesthesiologist’s Notes on Uncertainty. “In almost every other specialty, there’s tangible evidence of what they do, but with anesthesia, you don’t tan- gibly experience anything,” said Othman.

Beginning to write the book was not an easy or simple process. Dr. Othman had to find both the time to write and words to express what he described as an abstract thinking process that patients will never see. “It’s hard to explain something conceptual that that they patients can never experience,” said Othman. He began the process by reading many books about cognitive psychology, behavioral economics, philosophy of perception, and decision-making and was able to use language from those books and apply it to his own knowledge to put his thoughts into words on paper.

An Opportunity to Write

Cancelled elective procedures as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic provided Dr. Othman with time to work on the book. His workdays were reduced, and Dr. Othman was doing anesthesia all day and writing all night, the pandemic gave him a solid head start. “It took me months of working on end,” said Othman. “I set out to write a book, and I wanted to do it well, writing 1,0002,000 words per day.”

Dr. Othman wanted to explain the importance of anesthesiology in medicine. “The things we master in the operating room affects things outside of it too,” said Othman. The years he spent in medical school, as well as his expe- rience in the operating room served as inspiration for the book and drove Dr. Othman’s goal to help others better understand both the processes and passion behind anesthesiology as a profession.

The medical world continues to change and grow with the emergence of advancements in technology. Dr. Othman finds himself continuously impressed and excited about the evolving medical technology industry but does not see anesthesiology being an aspect of medicine that could rely 100 percent on it. ‘Black Swans’ is a term he uses in his book to describe the unpredictable events that occur in anesthesiology.

This unpredictability is why Dr. Othman believes in the necessity of a doctor. “There’s so much that patients don’t know about their medical care. That’s why you have a doctor there – doctors guide the technology and have it do what you need it to do,” said Othman. “It’s changed medicine for the better but it’s not a panacea. You still need experts to understand the technology and know when to use it and when not to use it. You want an expert in your corner to navigate that and give you the best outcome.” 1

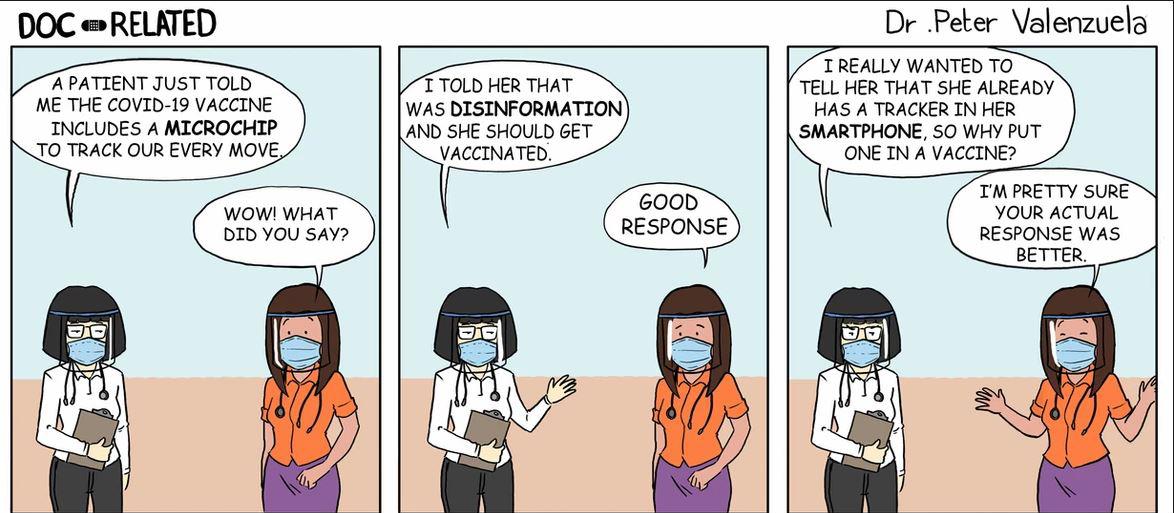

Microchipped Vaccine

Dr. Lam educates her patient about vaccine disinformation

Vaccines

Olympics Without Medals

Written by The Rev. Dr. Marta Illueca

The global race to develop effective vaccines against Covid-19 has unraveled the extent of the scientific and technological capabilities of mankind. Like an Olympic competition seeking the coveted gold medal, new vaccines emerge on the horizon in a race towards a finish line that challenges the nature and spirit of human beings. That great scientific Olympiad began a couple of centuries ago, with the history of vaccination. I would like to remind you, if I may, of the devastating global scourges of diseases like smallpox and polio. And now, instead of gratitude for the triumph of science in elucidating the identity and weaknesses of the new coronavirus, what we see is a tsunami of misinformation that generates division and mistrust.

Science Lessons

In the history of medicine, science has taught us to battle the unfathomable mystery of viruses and it has accurately decoded the name and signature of those viruses that attack and endanger the health of humans. Shortly after the first cases of COVID-19, we figured out the identity of the villain, a new coronavirus called SARS-CoV-2. The latest member of the coronavirus family would bring great devastation to the world. This group of viruses began its attack on human health in 2002, and it was then that efforts were initiated to develop a vaccine which was “shelved” due to the eventual suppression of that outbreak. Now the new pandemic reminds us that we have no cure for the coronavirus.

I want to emphasize that one of the most intriguing and disturbing legacies of science is to make us understand that for viruses, there are practically no effective medicines. For example, available remedies for bacteria are antibiotics like penicillin. These compounds have the ability to control and cure diseases caused by this variety of microbes. Unfortunately, they are not useful to treat viruses. The same goes for antiparasitic drugs. The reason is simple: there are too many virus variants and having a specific treatment for one, will hardly work for many others. Those medications that can help control a virus do so by affecting the genetic material of the virus, which depends on access to human cells to express itself. Therefore, these antiviral drugs have the potential to be toxic and of limited use for us. In- hibiting a virus “in vivo,” in the human body, entails causing “collateral damage” to the host tissues.

Therefore, there is no government or pharmaceutical company in the world with the necessary means to design and pay for effective treatments against all existing viruses. Only through a safe and effective vaccine will we be able to cut the vicious cycle and the ravages of the coronavirus. The history of medicine has proven it. Smallpox caused three hundred million deaths and was only eradicated thanks to vaccination in 1977. Polio left thousands of children paralyzed and was only controlled with vaccines in the West in 1994. Congenital rubella, a devastating disease for newborns, was finally controlled in the Americas in 2009 with its vaccine. And it was only in 2020 that an area of northeast Africa was liberated from Ebola, also thanks to a massive vaccination program. The same has been the case with diseases such as measles, mumps, tetanus, diphtheria, whooping cough, tuberculosis and rabies.

Ironic Mentality

The irony of the “anti-vaccine” mentality is precisely their forgetting about the ravages of the aforementioned diseases when left to run wild, but which thanks to vaccines, no longer exist or are hardly seen. Childhood vaccination protects children, and surprisingly many adults have no idea that they have been the beneficiaries of many efficient and safe vaccination practices, because words like polio and smallpox were never part of their vocabulary.

T he author is a physician, researcher and ordained priest with the Episcopal Church in Delaware and Fellow of the Yale Program for Medicine, Spirituality and Religion

Vaccines, like all medicines, have possible side effects. That is why there are international regulatory authorities that, based on the laws of each country, monitor the pharmaceutical development and the safety data of new treatments, each one for a specific indication.

In short, the development of vaccines has been the greatest science-based Olympiad in history and the athletes have been doctors, scientists, laboratories, governments and patients. There will be no gold, silver or bronze medals for the first vaccines against the coronavirus. And the final race isn’t over until all of the approved vaccines, together, contribute to the goal of herd immunity. Only then can we declare victory for COVID-19. 1

This article first appeared in La Prensa Newspaper, Panamá City, Republic of Panamá, January 24, 2021

Maggie’s Musings

D.O.’ING MEDICAL SCHOOL

Written by Margaret Hurley, Student Physician

Hello PO Readers!

I just finished Term 2… onto the final term of first year! This term we start out with a quick unit in head and neck anatomy and then we move to our first systems based course in Heme/ Onc.

Some reflections on Term 2. I really LOVE anatomy and physiology. I had the privilege to learn from dozens of cadavers this term, and every time I go into the lab, I am constantly reminded that I am working with someone’s mother or father, brother or sister, husband or wife. I walk in and see their brains carefully preserved in clear buckets - a window into their life - their every thought, memory and emotion. I am grateful to have had some wonderful “first patients.” As for physiology, it was definitely hard but fascinating to learn the normal workings of the body and it laid the foundation for the transition to pathology as we move on to systems.

A piece of careful advice to myself and anyone who embarks on the journey to medical school. Stop comparing yourself. Just stop! I saw a really cool analogy today “flowers are pretty but so are sunsets and they look nothing alike.” In medical school, your colleagues are some of the most intelligent and dedicated people. We are go getters, grinding non stop, always looking for ways to improve ourselves and those around us. It is easy to compare yourself to others on this journey, but it’s also important to be mindful that this journey is uniquely yours. At the end of the day, everyone is going to carry the title of physician and everyone’s path to get there will look different.

In college as pre-meds, we did a lot of “checking boxes” - clubs and ex- tracurriculars, research, shadowing and volunteer work. These are all important experiences, but never feel less if you are not able to do some of these things. In undergrad, I couldn’t bring myself to do wet-lab research (it seemed that every lab worked with drosophila or mice and that just wasn’t for me haha). Instead, I did educational research to learn more about study strategies for college students. My point is that if you feel the pressure to do something just to make yourself more competitive, take a step back and make sure you are doing it for the right reasons - because you WANT to! We are already going through some of the hardest years of our lives, and it is absolutely vital that you take the time to prioritize your happiness, sanity and wellbeing. 1

Happy vibes until next time, Maggie

1.

2.

3.

4.