5 minute read

After-Hours Author

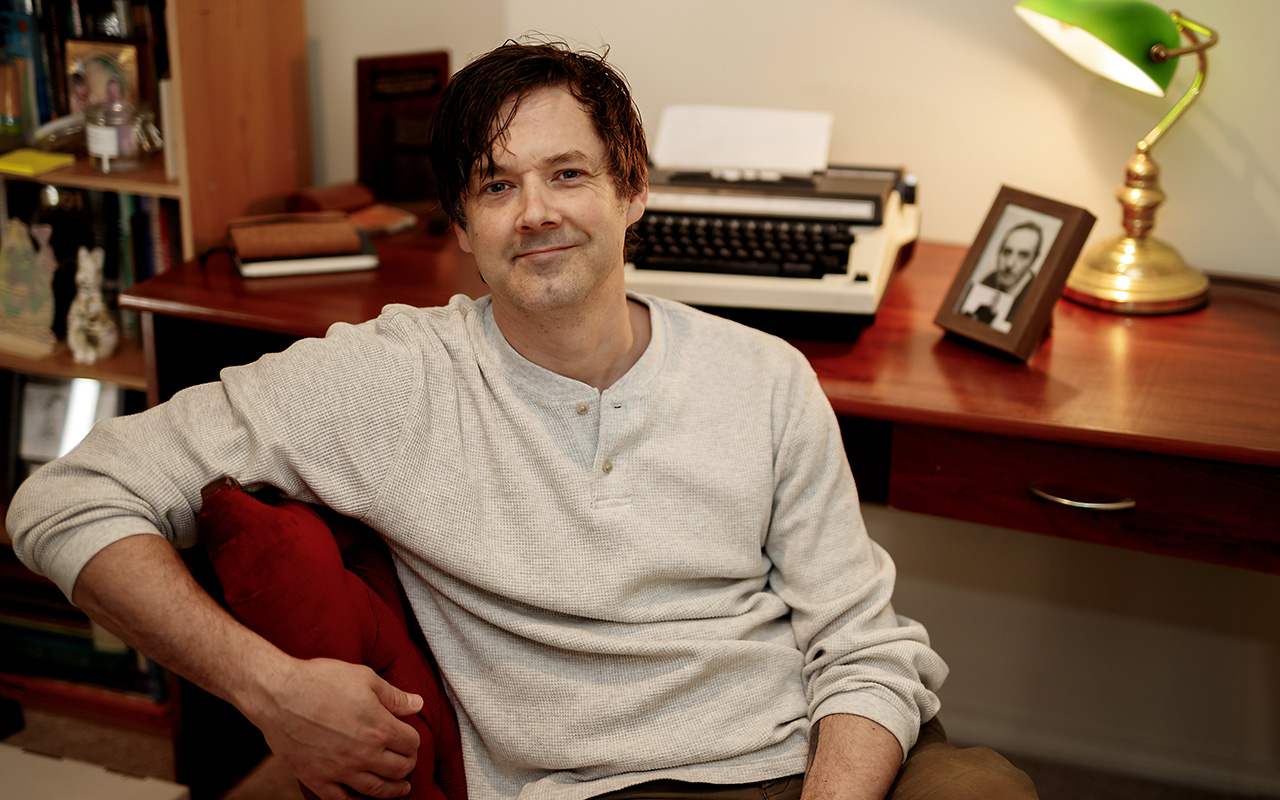

By Sarah Halfpenny Photos Yanni

Most award-winning authors eventually face a choice: pursue writing full-time or stay tethered to their day job. For Brendan James Murray, with a Ned Kelly Award under his belt, national recognition, and publishing deals with major houses, that decision might seem easy and obvious. Yet Brendan has chosen to stay in the classroom at Frankston High School, teaching English and English Literature to teenagers, while crafting his next book after hours and during school holidays. It’s a decision that speaks to his passion for education and his connection to the place that made him: the Mornington Peninsula, where he has lived for most of his life.

Growing up in Dromana during the 1980s and ‘90s, Brendan’s working-class upbringing influenced both his teaching philosophy and his writing. “I think certainly growing up in a working-class household shaped me in the sense that when I eventually became a teacher, I had maybe a little bit more of an understanding of what the lives of some of the kids I was teaching are like,” he explains.

His father worked “lots and lots of different jobs,” but the family always valued education. “Both my parents saw education as a way for myself and my brother and sister to have better lives than what they perceived their lives to be.”

That belief in education’s transformative power led Brendan to teaching, where he’s now spent 15 years in the classroom. His career began at Rosebud Secondary College – the same school he attended as a student – where he taught for over a decade. In 2023, when he realised “I’d spent about 50% of my life at that physical place” he decided it was time to broaden his horizons and made the move to Frankston High School.

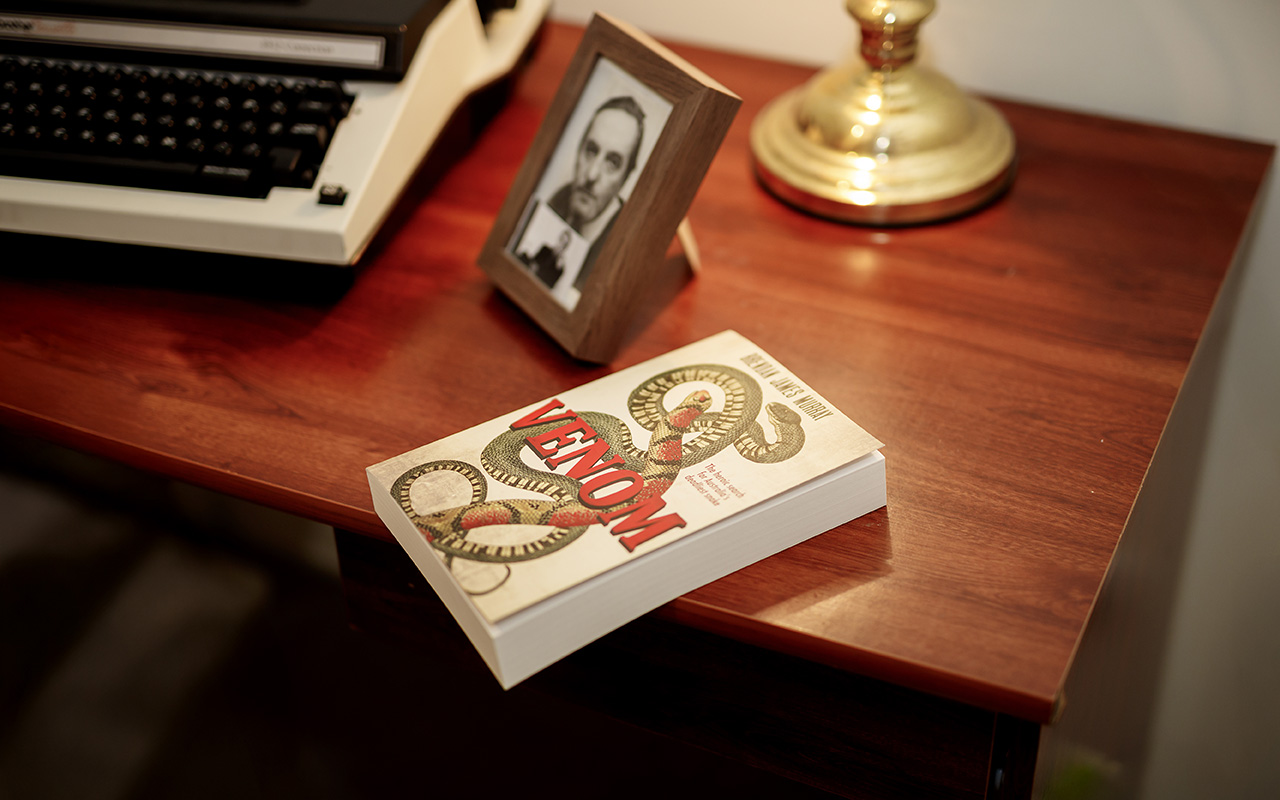

His connection to education runs parallel to his acclaimed writing career. From true crime to natural history, Brendan’s literary journey defies easy categorisation. His debut, The Drowned Man, won the Ned Kelly Award for Best True Crime in 2017, while Venom explored Australia’s deadliest snakes and earned a spot in the ABC’s Conversations ‘Best of’ series. His educational memoir The School – a powerful behind-the scenes look at modern teaching – was shortlisted for the NSW Premier’s Literary Award for Nonfiction.

What unites these seemingly disparate works is a common thread of advocacy. “The Drowned Man was about the mistreatment of homosexuals during the Second World War. Venom, although it’s about snakes, it’s about largely the mistreatment of Indigenous people. You could argue that The School is about mistreatment... or disadvantage, definitely,” he reflects. These are stories of the “overlooked or misunderstood or disadvantaged.”

The intersection of his teaching and writing creates a dynamic that enriches both pursuits. When he brings his vintage typewriter into class, students eagerly compete for the chance to use it. “Usually they’re fighting over it,” he laughs. His approach to balancing weighty subject matter in his books with the optimism required in teaching reveals his nuanced understanding of both roles. “You have to be hopeful as a teacher. The nature of the job, in some ways, is this purely optimistic, forward-looking way of being, where you’re looking at young people, and you’re thinking about what they could be.”

His upcoming book with Pan Macmillan promises to be his most personal yet. This new project examines education and childhood through the lens of parenthood. “It’s the first book I’ve written since becoming a parent, and in some ways that’s really intensified this sense I have of wanting to be really clear in my own head about what kids need, and what’s going to position them to get the most out of life.”

As a writer who teaches English, it makes me think about language all the time

The book weaves together memoir and educational philosophy, exploring “myself when I was a little kid, myself as a parent and myself as a teacher,” he says. At its core lies a passionate argument for reimagining how we nurture young minds. Brendan believes “we need more education, and more imagination in education”; something he sees as having “strangely fallen by the wayside across all of western society.”

He’s particularly frustrated by how imagination becomes relegated to early childhood or business contexts, rather than being recognised as “that kind of fun, playful imagination that can be really nourishing and important for people.” The book draws on his observations of students, some of whom can vividly imagine themselves as archaeologists, while others respond with “I don’t know” or “Nothing!” when asked about their interests or future plans.

Despite his literary acclaim, Brendan remains devoted to teaching. “As a writer who teaches English, it makes me think about language all the time. I think it probably makes me a better writer, having those nutsand-bolts conversations every day, and thoughts about what makes good writing.”

The classroom also provides endless inspiration. “I really love working with the kids. It’s fun and it’s funny. It’s challenging in a good way,” he says, describing himself as “one of those lucky people who really, really enjoys their job.”

His commitment to staying local runs deeper than career convenience. “I feel a genuine connection to the Mornington Peninsula. I’ve grown up here. I’ve had so many experiences here. My kids were born here. I met my wife here,” he explains. “People travel all over the world to see places like where we live. It really is a very beautiful part of the world.”

For Brendan James Murray, success looks different from the usual modern-day narrative that pushes for constant movement and relentless ambition. It’s about contentment in doing work that feeds both his creative soul and his desire to make a difference, right where he belongs.