9 minute read

The Day Fire Struck the Peninsula

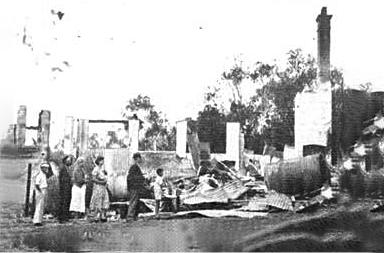

Above: A Dromana family overlooks all that remains of their home after the fire

By Peter McCullough

The Black Friday bushfires of January 1939 in Victoria were part of the devastating 1938-39 bushfire season in Australia which saw fires burning for the whole summer and ash falling on the glaciers in New Zealand.

In Victoria, Black Friday, 13 January, was in fact the worst day in a spell which extended from the previous Sunday through to Sunday 15 January when most welcome rain fell across the state. It is now recognized as the third deadliest bushfire event in Australian history, only behind the 1983 Ash Wednesday and 2009 Black Saturday bushfires.

On 13 January 1939 the temperature in Melbourne reached 45.6 C (114.08 F) with very low humidity levels. Large areas were affected and smoke covered 75% of the state. Narbethong, Noojee, Woods Point, Nayook West and Hill End were completely destroyed and many other towns were severely damaged. The total number of lives lost in January was 71 (36 on Black Friday alone) and 3,700 buildings were destroyed or damaged including 1,300 houses and 69 sawmills. The fires burned almost two million hectares (4.9 million acres) and resulted in the deaths of thousands of cattle, sheep and horses as well as untold native animals. Where the fire was most intense the soil itself was burnt to a considerable depth.

There were a number of horrific stories of those caught in the path of a fire. In the Matlock forest men at two sawmills were trapped. Some tried to make a run for it only to die in the flames; one jumped into a water tank thinking that he would be safe, but he was boiled alive when the fire swept through. In total 16 men were killed.

How was the Mornington Peninsula affected by the Black Friday bushfires? In fact the peninsula had an early taste of what was to come as bushfires caused havoc in Dromana and, to a lesser extent, Frankston on Sunday 8 January.

Dromana

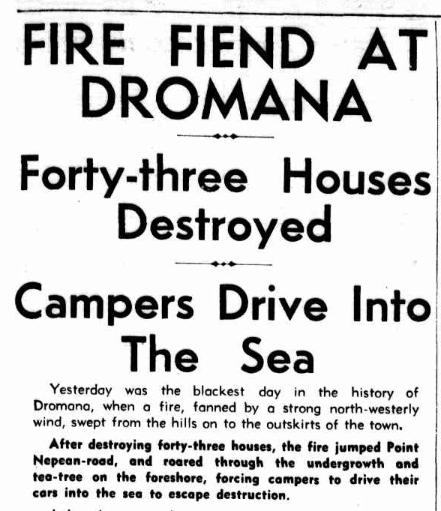

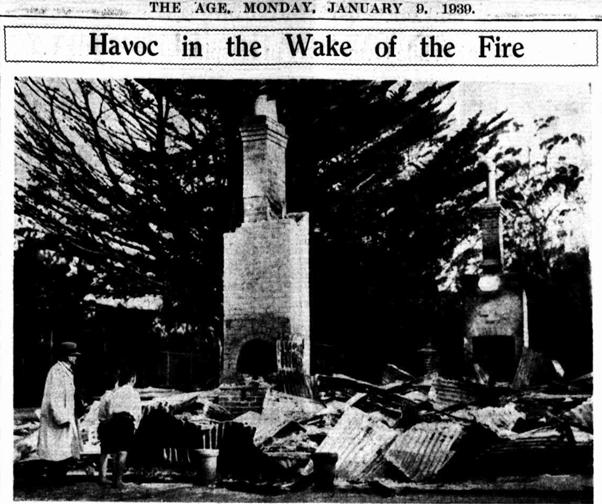

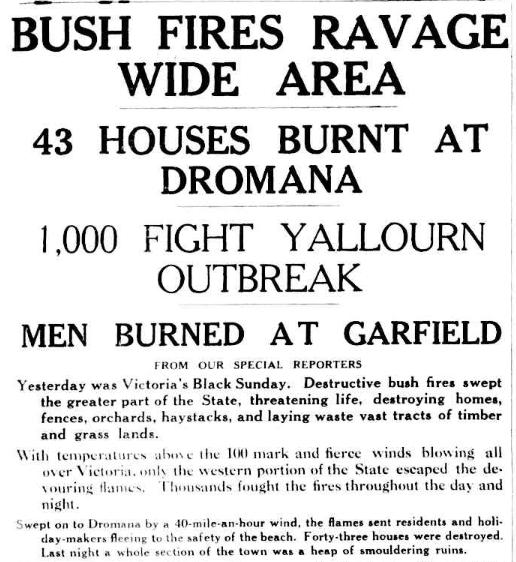

The headlines of the article in The Age of Monday 9 January expressed the horror that gripped Dromana on the previous day: ‘Fire Fiend at Dromana’, ‘Forty-three Houses Destroyed’ and ‘Campers Drive Into the Sea’. The situation is summed up in the opening few sentences: “Yesterday was the blackest day in the history of Dromana when a fire, fanned by a strong north-westerly wind, swept from the hills to the outskirts of the town. After destroying forty-three houses, the fire jumped Point Nepean Road, and roared through the undergrowth and tea-tree, forcing campers to drive their cars into the sea to escape destruction. A hastily recruited army of fire-fighters was powerless against the roaring flames, and only a fortunate change in the wind saved the entire town from destruction.”

The fire appeared to start late morning in a gully “near the seaside home of the Fareys of Glenferrie Road, Hawthorn”. Soon “half a mile of the Bayside was alight”. The flames swept towards Arthurs Seat, two miles distant. “The slopes of the mountain are studded with holiday homes, and all which came in the path of the fire were destroyed. So rapid was the sweep of destruction that there was no possibility of saving even lighter articles of furniture. Indeed, in many cases, furniture was rushed out of the doomed houses only to be ignited by flying debris and destroyed on the road.”

The alarm was given in nearby resorts and within a short time over 300 “willing fighters” gathered to fight the onrush of the flames. “Sparks and blazing debris were often carried 100 yards to start a fresh outbreak over the heads of the fighters. In many cases the onrush was so rapid that they had to beat a hasty retreat to avoid being involved in the general destruction.”

Sweeping up everything in its path, the fire soon reached the foreshore and in a matter of minutes fifty foreshore camps were menaced. There was barely time for the holiday makers to start the car, link up the trailer or caravan, and drive pell-mell to the sea, abandoning tents, clothing and camping equipment to the flames. Even at the water’s edge the heat and smoke were stifling. People who had taken shelter there had to cover their faces with towels soaked in sea water.

The Age report provided a comprehensive list of houses destroyed. “Nearly all were not occupied by their owners, but had been let for the holiday period to visitors from the city. These were clad enough to escape in the clothes they were wearing, leaving the rest of their belongings to destruction. Some unfortunates had just returned from their morning swim and had to return to their city homes clad only in their bathers.”

Some of the holiday homes mentioned in the account had quirky names such as ‘Topsy Turvey’, ‘Higgledy Piggledy’, the ‘camp of the Women Haters’ and the ‘Home of the Trained Nurses’ which had ten nurses in residence. Although the house of Hector Greig was destroyed, some of the furniture was saved including “a frigidaire”. The Age reporter commented: “It contained a generous supply of liquid refreshment, and with the hearty good will of the owner, it disappeared as if by magic. It is possibly the first time in the history of fire destruction that the fire fighters have been served with liquid refreshment ‘off the ice’ in the heart of a conflagration.”

No one was spared. “Among the visitors to Dromana was Rev. T. Rentoul. He was at divine service at the local Methodist church when the church bell sounded the fire alarm. The service was abandoned and the males of the congregation joined the fire fighters. Mr. Rentoul was one of the first on the scene, but later had to watch his own house in the grip of the flames. Nothing was saved.”

The other popular newspaper, The Argus, also had a comprehensive account of the event which included this story: “A remarkable escape was that of Mr. and Mrs. C. A. Kennedy who live at the corner of Latrobe Parade and Grant Street. Because of the heat earlier in the morning they had drawn their window blinds. They were having luncheon about midday when Mrs. Kennedy happened to raise one of the blinds. She was astonished to see that a wall of flame was descending upon their home.

While the adjoining house owned by Mr. M. Owen was burning, Mr. and Mrs. Kennedy bundled clothes from their wardrobes into suitcases and ran to their car. On returning to the car with a second load of suitcases, Mrs. Kennedy found that the car had caught fire.

Mrs. Kennedy dropped the cases and obtained a bucket of water with which she extinguished the flames. When Mr. Kennedy joined her a few moments later he found that two bags inside the car were ablaze. He returned to his house and fought the flames for a few minutes but was forced to retreat by the heat and the smoke.”

Both newspapers carried reports of praiseworthy behaviour: “In the confusion attendant on such widespread destruction, individual acts of heroism passed unnoticed. There were many timely rescues. When the house of Mr. Mathieson caught fire, an elderly woman, Mrs. Kerr, whose son and family were in the house, was resting in her room. The rear of the building was burning fiercely as she was being carried to a place of safety.” (The Age) “Several invalids were carried out to cars which were driven along streets in which houses were already blazing, and women who had fainted from shock and the intense heat were carried by men to the beach.” (The Argus)

The correspondent from The Age concluded his report on a positive note: “Residents congratulate themselves that although there has been such extensive loss of property, no lives have been lost.”

Frankston

The Age of 9 January 1939 contained an article headed ‘Frankston’s Worst Fire’. Claimed to be the worst outbreak ever experienced in the Frankston district, it swept across a wide area and destroyed five weatherboards. The Argus reported “The town was covered with a thick pall of smoke and the alarm bell tolled almost continuously throughout the day”.

It was a case of ‘all hands on deck’ for among the 600 who reportedly fought the flames were Major-General Grimwade, Sir T. Blamey and Sir H. G. Smith. Many of the volunteers were holiday makers and were clad only in shorts and athletic singlets; they “emerged from the scene temporarily blinded by the smoke and blackened by the dust and flying cinders”.

The flames spread from near the former Jamboree site at the south of Frankston and raced towards the town. “In the vicinity of Woodlands Grove scores of houses were endangered, and epic battles were staged to save each one as the flames reached them.” None-the-less three weatherboards were destroyed and a bungalow was burnt to the ground.

Before long the fire was endangering scores of houses in Yuille and Denbigh Streets. It jumped Yuille Street and swept through dense scrub and tea-tree which burnt fiercely. Many houses and weekend shacks in this area were hurriedly abandoned by their occupants. In Denbigh Street many residents stacked valuables in the street in preparation for a quick exit from their homes. However, due to the efforts of firemen and volunteers, only two small weatherboards in this area were destroyed. The fire burnt to the municipal golf links about a quarter of a mile from the town centre.

The Frankston fire burnt over an area of about five square miles, and in many cases fences and hedges were ignited before the flames were beaten out, Because of the much larger number of fire fighters and possibly the topography, the losses in this fire were minimal when compared to the blaze at Dromana. Again, fortunately, there was no loss of life.

Birth of the CFA

The infernos of January 1939 had a momentous impact on Victoria’s management of fire, leading to the establishment of the Country Fire Authority.