12 minute read

“WE’RE A BRAND ANCHORED AROUND SOCIAL GIVE BACK.” –Lauren Bush Lauren

when she was given the opportunity to travel with the UN World Food Program, which really set her on the path to starting FEED so that she could support their great work. “On the one hand, I was studying, and I also had the opportunity to travel and get that on-the-ground exposure. Between my junior and senior year, I was able to get funding, so I spent most of the summer in Africa doing research and taking pictures, and it was also an educational experience, so anthropology pairs nicely with that.” Determined to make a difference, Lauren had the FEED bag prototype by the time she graduated, and through that was able to go out and raise money for the UN Food Program in 62 of the poorest countries around the globe. In addition to feeding kids nutritious meals, it also encourages and incentivizes them to go to school. Because of FEED, kids in Asia, Africa, and Latin America are getting a healthy meal and an education for their future.

“I wanted to create a way for other young people to give back, and world hunger is a massive issue. There are 800 million people around the world who are hungry, and 9 million children in the US alone live in food-insecure households. When visiting these families and communities I couldn’t help but leave thinking, What can I do to help? What I thought of was turning the consumer into the donor. Now, they can wear their values and support something where they know where their money is going and what it’s doing.” She officially started the company a year later, and fast-forward to today, 15 years after the launch, FEED is still going strong, with 126 million meals served and counting. FEED was also started in the early days of doing commerce for good. “We’re a brand anchored around social give back and social issues, and I’m so proud that we are 15 years in and are still around and making school meals and raising awareness around hunger.” With a mission to be both functional and feed others, the initial FEED bag was mostly inspired by the bags of grain and rice she saw being distributed to kids in schools globally. Lauren also likes the utilitarian aesthetic, which is why even the feed logo has an older, industrial look.

Commerce for Good

This commerce-for-good concept was almost avant-garde back then, as the FEED bag was around even before Toms was giving away shoes. This for-profit business model also measures giving in terms of meals. Lauren says that she is really glad to see that commerce has evolved to a point where it’s expected of brands and companies to have a purpose and give back.

“I went into FEED saying our main mode of raising money is a brand because I really love fashion and design and had the passion and curiosity to pursue it. FEED was really this ‘aha’ moment of realizing I can combine this desire to be a designer and entrepreneur but with a real vehicle to give back to kids who don’t get to have a meal in school. One of my greatest joys is seeing how other companies have stepped up and are doing so much for the community, so we are no longer an anomaly like we were when we started. Each bag we make has a number, which signifies the amount of meals we are able to donate through the sale of that product. We know how to solve hunger, and there’s a cost to that meal. The highest level of giving is a bag that feeds one child in school for a year, while the rest also provide the price equivalent to the meals.”

Though the price of a meal varies depending on where they are giving, the global average of a meal is 15 cents. FEED also works with the best-in-class partners and organizations who are on the ground serving the meals. This extends to the UN World Food Programme, where Lauren’s whole journey started, as well as No Kid Hungry, their American partner, and also an Indian-based partner. These are their three main giving partners.

Leading by Example

Lauren also explains how her family, including her grandparents, inspired her by leading by example, something that left a strong impression, evidenced by the fact that her siblings and her cousins have found their own paths to lead a life of service. “Doing something that helps others beyond you is a good path to choose, and I’m lucky I had those examples to learn from.” Another person she considers to be a role model is longtime family friend Bill Clinton, who even came out to support her when he spoke at a Clarins event she was a part of at Lincoln Center, which helped to raise an incredible amount of meals. It was a humbling and meaningful moment, especially when he referred to Lauren as being ‘the real deal.’

Summer White House: Kennebunkport, Maine

She also recalls some of her earliest memories in what she still refers to as her happy place, the family compound in Kennebunkport, Maine. “Barbara was keeper of the rules, so you definitely didn’t want to leave towels out or a bike thrown on the lawn. Literacy was her big cause, so for one hour each day we would all come in her room with our books and do our summer reading. She was always very funny and loving, but you didn’t mess with her! The summers were a big task with such a big family coming and going, and we have always been very active and competitive, whether it was playing tennis or now a pickleball match or swimming. We would basically move there in the summer and felt super lucky to have this cool escape from Texas. We would even drive our boats to town, and as a kid, it was so great having that freedom and was also pretty unique and special. It was really like a camp environment. We all return every summer, and it’s so wonderful to have those old and new memories.”

Though she might be a Texan, the always inquisitive and forward-thinking Lauren, traits that have led her to help solve world hunger in the most stylish way possible, became a vegetarian at the age of four or five once she realized that animals had a face and put together that meat came from animals. While her mom thought she would grow out of this phase, she continues to choose not to eat meat and appreciates all the plant-based options out there these days. She also had a chance to hone her cooking skills during Covid and enjoys a good curry or soup. Her husband and kids are indeed fans of her healthy dishes, but they haven’t given up on hamburgers just yet.

Lauren Met Her Husband at The Met Gala

With a match made in Met Gala heaven, which led to a rustic chic wedding tucked away in the Rocky Mountains, Lauren and her husband, David, have now been married for almost 12 years and continue to go back to the glitzy gala every year as an anniversary of their initial meeting. After they met while leaving the Met and having David’s sister, Dylan, as a point of reference due to Lauren’s friendship with the candy entrepreneur, Dylan helped arrange a group dinner that helped to further solidify a friendship that progressed to a seven-year courtship. When he finally proposed in 2011, David transformed the Met into a side gallery showcasing true masterpieces—photos of them together over the years.

The wedding took place at the Ralph Lauren ranch with 200 guests in attendance. Wearing blue socks under cowboy boots, Lauren got to be totally herself, and in true Ralph Lauren style, no detail was spared for the magical occasion. The dress is now in the Ralph Lauren archive.

While over the last 15 years FEED has partnered with brands and retailers including Williams-Sonoma, Ralph Lauren, Judith Leiber, National Geographic, and many others, and even evolved to other products, such as home collections with items related to food as well as candles and scarves, Lauren is already looking forward to more ways to feed the bodies as well as souls of others around the world. P feedprojects.com

Instagram: laurenblauren

BY ANTHONY HADEN-GUEST

eid Stowe has had two lifelong passions, making art and sailing, usually long distance, and there are fresh developments in both. His first show with Chase Contemporary opened on March 23rd at their West Broadway gallery, and in June he will be setting off on Anne, the schooner he built by hand at the age of 25. This would be the first of a series of voyages with a crew of wannabe astronauts he will be observing. Their reactions to the pressures of being cooped up in cramped quarters will be closely monitored. This is a project that has the backing of NASA and the support of the Mars Project, a core interest of Elon Musk.

It’s been a long trip for Reid Stowe, who is now in his early 70s, and sometimes, yes, a strange one. He built his first boat, a small catamaran, on a waterway near his home in North Carolina at age 20 and named it Tantra, after another of his passions, tantric yoga. “It only weighed 1,400 pounds,” he says. His art was an add-on to the weight. As an art student at the University of Arizona, he had carved figureheads and been influenced both by the Nazca Lines in Peru and Richard Long, a Brit who made art by walking through the land. It was also a time of Extreme Performance, a time when Philippe Petit, also a former art student, wire-walked between the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. Stowe would perform aboard his boat wearing a mask. In 1973, he made a solo crossing of the Atlantic, fortifying his marine charts with images of goddesses. “I was painting for my protection,” he says.

Needful protection. Stowe was aware of the story of another artist/sailor, Bas Jan Ader, a Dutch Conceptual artist, who had taken off alone from Cape

Cod in a 13-foot pocket cruiser on July 9th, 1975, his departure celebrated by a group singing sea shanties. Ader called this Performance piece, In Search of the Miraculous, and estimated it would take two and a half months. His boat was found floating off the Irish coast ten months later. His body was never recovered.

Reid Stowe’s voyages grew longer, and he frequently took along a paying group. In 1986 he sailed to the Antarctic on Schooner Anne, his second boat, built when he was 25, with a crew of eight artists, including painters, musicians, and a comic. “Usually, it’s just scientists who get to go there,” he says. For five months they circumnavigated Antarctica, threading their way through icepacks and lashed by icy 100-MPH-plus winds. It was in Antarctica that Stowe decided upon a future project. A biggie, a recordbeater: one thousand days at sea.

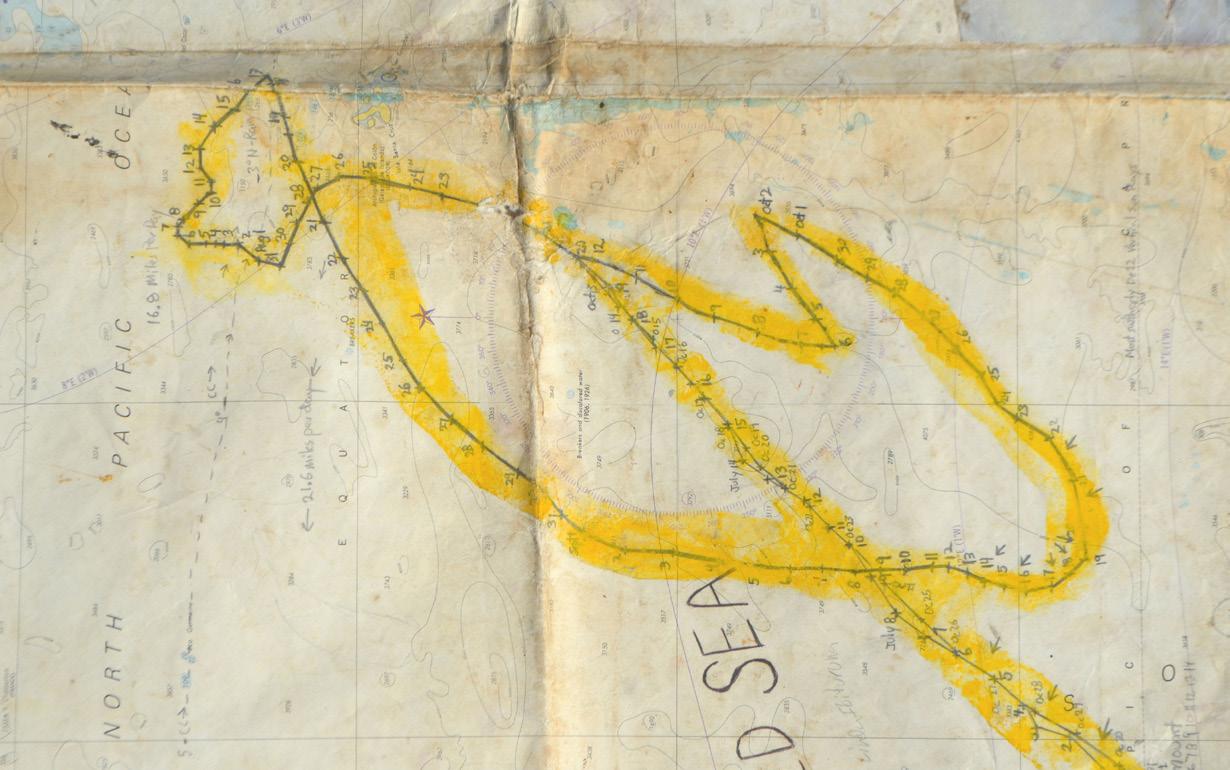

That was for the future, though. Further voyages followed in the meantime, and much more art, sometimes the two being intertwined. “I invented GPS Art,” Stowe says. This was inspired by Richard Long’s walks through various landscapes, and Anne became Stowe’s drawing instrument on the seascape, his course being recorded by the Global Positioning System. He made The Odyssey of the Sea Turtle, his first piece, in 1999, intending a voyage that would outline a turtle. “It was contingent on my understanding the winds and the currents,” he says. But he had to contend with strongly contrary winds when he reached the bottom of the shell in the middle of the South Atlantic. “I ended up not drawing the flippers at the bottom,” he says. “So now it’s the sea turtle hatching out of the shell.” This piece of maritime artmaking followed by others, such as Whale GPS Chart Painting, 1964-2019, upon which he collaged relevant documentation, such as a self-portrait he painted at the Equator, the chart he used upon his 1973 Trans-Atlantic crossing, and the GPS charts that had defined the whale-shape.

The Big Trip was never off Stowe’s mind, though. On July 20th, 1989, some months after his return from Antarctica, President George Bush announced plans for a trip to Mars. “They were planning to send six to eight people. Men and women,” Stowe said. It was instantly clear to him that the physical and psychological pressures of being cramped together long-term in an extremely small space that he and his crew had endured on the Antarctic trip indicated real parallels between that experience and travel those on a space capsule.

It was also clear to him that the likeness would be all the stronger when he and whoever he chose to accompany him would be selfbanned for three years from getting fresh supplies of food, drink, or equipment during his forthcoming Big Trip. Which he promptly renamed 1,000 Days at Sea: The Mars Ocean Odyssey.

Reid followed up by writing a piece indicating that ocean voyaging could be a learning experience for fledgling astronauts, and he gave talks on the subject. This got NASA’s attention. Meetings followed, at which they discussed the use of Schooner Anne to check the suitability of the wannabes—NASA calls them analog astronauts— and this was plain sailing. But then there was a squall. Stowe, an old-school hippy, had financed his voyages from early on by smuggling pot from Latin America and the Caribbean. He was now indicted for bringing in a hefty load, the bust being in his SoHo loft. “They never found my main grow room,” he says cheerfully.

Stowe served a nine-month sentence, and when he got out, NASA was out the door. But The Mars Ocean Odyssey project continued, and on April 21st, 2011, Stowe and Soanya Ahmad, his young wife, set sail from Hoboken. Marine excitements began early, with them being run down by a container boat in the early morning on Day 14. They lost their bowsprit, and Stowe carpentered a replacement, but it was kind of a stump, making the boat harder to maneuver. Some months later, Soanya found she was pregnant. She insisted that the voyage continue, so Stowe called Jon Saunders, holder of the then-long-distance sailing record, on a sat phone. He took her aboard his craft eleven miles off Australia, and Stowe headed for the Pacific. That was Day 306.

Sheer survival required Reid’s constant maintenance, including the patching of sails and the fixing of devices, as when his desalinator stopped working. “I had four big water tanks,” he said. “I had to sail to Galapagos on the Equator so that I could lower my sail and catch rainwater.”

Artmaking also continued, and an artwork can record a sailing experience, sometimes a scary one. As on Day 657, when Schooner Anne was overturned by a monster wave rounding Cape Horn. Stowe was knocked out, but Anne righted herself, and another icy wave brought him back to his senses. He saw that the sail he had spent forever hand-sewing was now wholly shredded, which was bad. But also good. “I instantly thought I’d make a great painting out of that,” he said, “and got to work on usable areas of the sail.” The Capsize Painting, a five-by-seven-footer, includes the grommets, rope, and piles of sawdust produced by the necessary boat repairs, along with collaged material from his personal documentation.

The last year of the 1,000 Days was the easiest, and Stowe was painting several hours a day. “I could paint in my pilot house in all weathers,” he says. When the weather was good, he worked on deck, laying out the canvases and working in all media. He made something like a hundred artworks.

“As I sailed up into the South Atlantic Ocean, the weather grew much nicer, and I drew a GPS drawing of a giant heart in the South Atlantic Ocean. It was satellite verified, and that was meaningful for me that I was able to do that with a disabled boat with torn sails. I was in the Trade Winds, and those beautiful waves were rocking me all the time. I counted them numerous times. There were thirty thousand waves a day, rocking.”

Stowe had picked the date and time of landing six months in advance. “I looked at the tides,” he said. “There, tide would rise and put me on the dock in midtown Manhattan at one o’clock on Thursday, June 17th. It was perfect—the motor worked; the sails worked. I saw my woman, my daughter, and my son, Darshen, for the first time. And I saw a lot of people I love.”

Reid Stowe is in the Guinness Book of World Records as having made the longest such ocean journey, 1,152 days, without ever touching land.

And it continues. “I call her the Starship Schooner Anne now,” he says. His first journey with the eight analog astronauts will take them straight out from Manhattan into the ocean for two weeks before returning. It will be at the beginning of June. Till then, he will be engulfed by an equally demanding presence, the New York Artworld. Go see the remarkable work that has come directly out of a remarkable life at Chase Contemporary. P reidstowepaintings.com

The University of Michigan Museum of Art & The Bronx Museum of the Arts

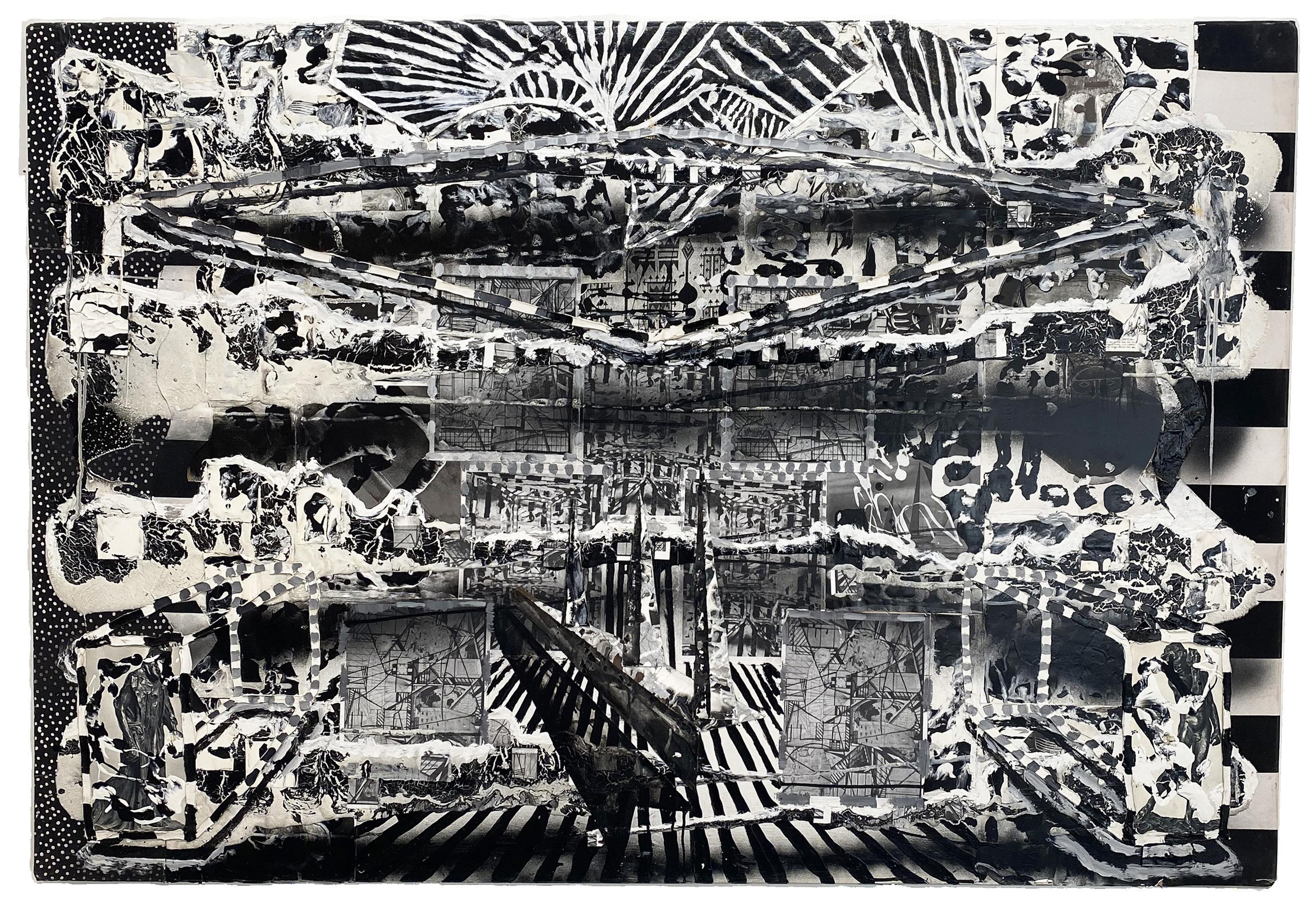

In a remarkable 25-year career, artist Marcus Jansen has progressed from selling his work on the corner of Prince Street and Broadway in Soho to showing in museums and galleries around the world. One of the most prolific artists to emerge from the graffiti school of 1980s-1990s NYC, Jansen’s work is now in the permanent collections of the Bronx Museum of the Arts, the Baker Museum at Artis-Naples, the Rollins Museum of Art in Orlando, the University Of Michigan Museum of Art, the Moscow Museum of Modern Art and the Perm Museum of Contemporary Art (PERMM), both in Russia, and the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, among others. Throughout his career, Jansen’s work has dealt with socially and politically charged issues, including inequality, the environment, and power structures in our culture, and he is considered a pioneer by critics and historians in this respect.

Examine & Report: A Documentary

In Marcus Jansen: Examine & Report, a 2016