10 minute read

Trans-Alaska pipeline: the future

Figure 1. Alkaid #2 Drilling Site. (Source: Pantheon Resources plc)

Recent discoveries on the North Slope could act as a solution to a reliance on foreign energy, says Jay Cheatham, CEO, Pantheon Resources, USA.

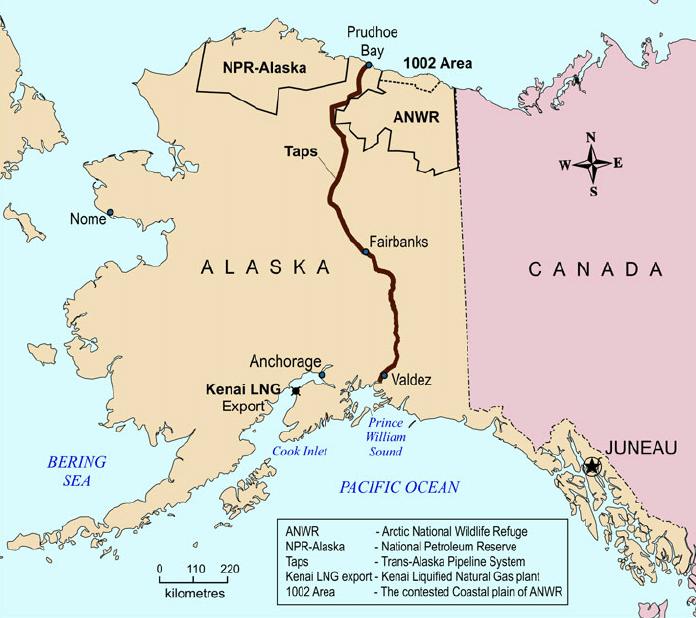

hen it was built, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline was designed to deliver around 9 billion bbls of North Slope oil over a 20 year operational life. However, it has gone above and beyond expectations, celebrating the delivery of its 18 billionth barrel in December 2019 and its 45 year anniversary in June 2022. The Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) is an 800 mile pipeline connecting Prudhoe Bay on the North Slope of Alaska to the Port of Valdez in the South. Its inception stems from the first discovery of oil in Prudhoe Bay in 1968, which led to the subsequent formation of the Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. (Alyeska) in 1970. The objectives of Alyeska were to design, construct, operate and maintain the pipeline. The Trans-Alaskan Pipeline Authorisation Act was passed in the US Senate in 1973 after Vice President, Spiro Agnew, cast a tie-breaking vote and the first section of pipe was laid two years

later. The pipeline construction project involved 70 000 workers between 1969 - 1977 and, at the time, was the largest private construction project in American history. On 20 June 1977, first oil moved through the pipeline from Prudhoe Bay and arrived at the Port of Valdez after 38 days. Today, the pipeline is still owned and managed by the Alyeska Pipeline Service Co., which is a consortium made up of Harvest (Hilcorp), ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, Unocal and Koch.

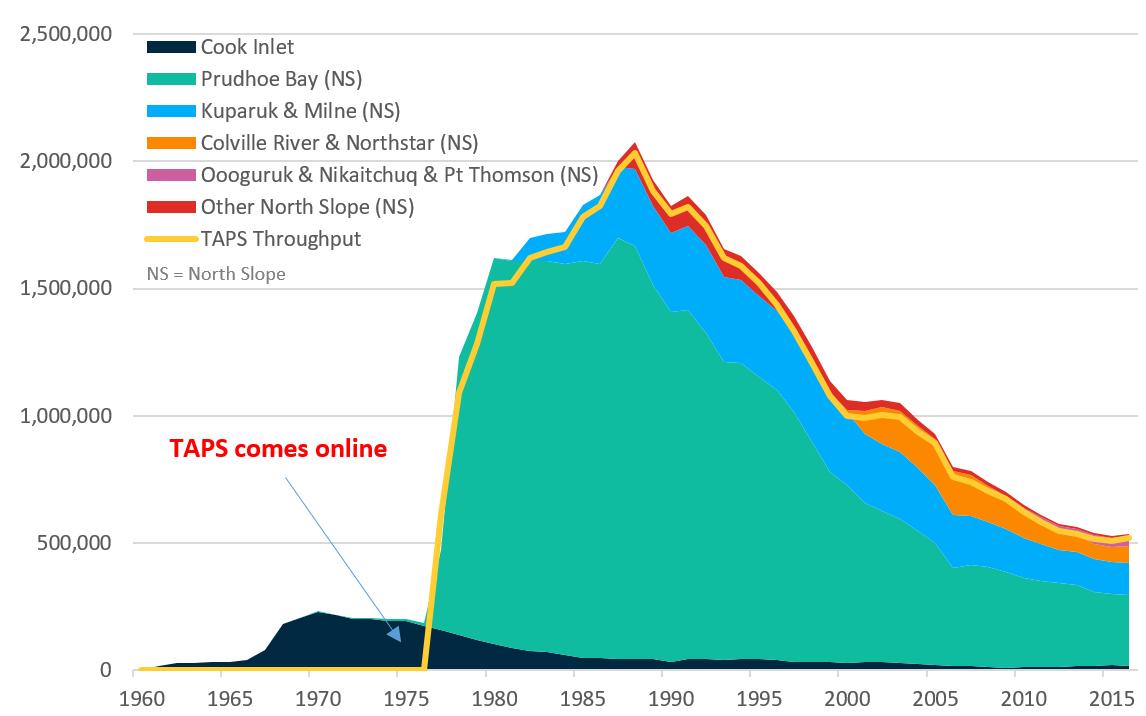

Since reaching peak capacity at around 2 million bpd in 1988, there has been a gradual decline of throughput to around 448 000 bpd in 2020. This has led to issues as, with reduced throughput, the oil can cool and thicken if it is not able to pass through the pipeline fast enough. Despite this decline, there have been a number of noteworthy discoveries in recent years, which operators claim could be of immense benefit to the pipeline. Prudhoe Bay is the largest oilfield in North America, and is amongst the top 20 discovered in the world, so it is no surprise that companies are still constantly exploring for new fields in the region. Examples of recent discoveries and estimated recoverable resources include: ) Caelus Energy (2016) – Smith Bay, 2.4 billion bbls recoverable.

) ConocoPhillips (2016) – Willow, 400 - 800 million bbls recoverable. ) Oil Search (2017) – Pikka-Horseshoe, 1.2 billion bbls recoverable.

) Pantheon Resources (2021) – Theta West, 1.7 billion bbls recoverable.

Celebrating its 45th anniversary, Alaska Senator, Lisa Murkowski said that TAPS has been the backbone of Alaska’s economy, supported thousands of jobs and has helped generate billions of dollars of critical revenue for the State of Alaska. In 2017, BP said that since its launch, Alaska has earned US$141 billion from North Slope production and development. Murkowski also emphasised the importance of TAPS as a “vital component of America’s energy security”. TAPS has had a significant impact not only on the State of Alaska, but on the oil industry itself. According to BP, the Prudhoe Bay oilfield has been a “proving ground for advanced drilling techniques, including multi-lateral and coiled tubing, now employed by oilfields across the globe”.

How can TAPS survive and thrive in the face of challenges today? There has been concern across the industry and media about whether TAPS has a viable future, mostly due to declining production from the ageing producing oilfields of Prudhoe Bay and Kuparuk, as well as the challenges surrounding thawing permafrost and the potential problems this can pose.

Falling production Alaska oil production peaked in 1988 at about 2 million bpd, the only time in which the TAPS maximum capacity has been utilised. This accounted for around 25% of US oil production at the time. Throughput has declined over the decades, standing at around 560 000 bpd in 2013 and then 448 000 in 2020, accounting for 7% and 4% of total US production, respectively. In addition, TAPS was originally built with 11 pump stations, but this number now stands at four. When TAPS was carrying 2 million bpd of oil at its peak, the oil took four days to move from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez. Now, with rates around one quarter of this, it takes about two weeks to make the same journey.

The problem associated with the oil cooling and thickening is that it creates a build-up of wax, water and

Figure 2. Map of Alaska showing the route TAPS takes. (Source: Energy Information Administration)

ice in the pipeline, which means that Alyeska has to use a process known as ‘pigging’ to clean the walls to prevent any further issues. Pigging is just one of the various engineering approaches taken by Alyeska today to deal with reduced flow, but those in Alaska argue that these steps shouldn’t need to be taken:

“Although Alaskans continue to devise safe and innovative solutions to move the oil from matured fields every day, the best long-term solution lies in the billions of barrels of oil that are nearby and can be responsibly produced”, says Thomas Barrett, President of the Alyeska Pipeline Service Co., 2016.

To combat the decline in production, Alaskan officials and politicians have been working to open areas of the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) to drilling, which has previously been prohibited. However, in 2022, five years after Congress mandated an oil and gas programme in ANWR’s 1002 nonwilderness area, this has been blocked by President Biden.

As well as the economic benefits for the State, producing oil in Alaska and transporting it through TAPS is also extremely important when considering the current geopolitical situation. Strengthening production once again in Alaska would help to bolster the US’s energy security, and reduce dependence on Russian and Middle Eastern oil given the energy crisis the world is currently facing. In her recent speech, Senator Murkowski invoked memories of how TAPS helped the US during the 1979 oil crisis, and enabled the country to insulate from OPEC and OPEC+. For Alaskan politicians, the hope is that the need to affirm the US’s energy security and energy independence will act as the impetus to revive exploration activities across the State. North Slope – the saviour? ConocoPhillips, the largest producer in Alaska, stated that drilling on the North Slope “is expected to continue for many years”. When production started at Prudhoe, the recovery factor for the 25 billion bbls of oil in place across the oilfield was expected to reach 40%. However, innovations in oilfield technology have allowed ConocoPhillips to increase the estimate to more than 60%. In 2021, ConocoPhillips alone produced an average of 197 000 bpd, mostly from Kuparuk and the Prudhoe Bay unit.

As previously mentioned, current levels of production are not sufficient to maintain TAPS going forward.

Figure 3. Alaskan Crude Oil and NGL Production and TAPS Throughput 1960-2016, in bpd. (Source: Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. and Alaska Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (AOGCC) data) According to ConocoPhillips, Prudhoe Bay has over 800 active oil producing wells, and several high-profile discoveries recently have provided some optimism amongst North Slope operators that TAPS will be able to thrive once again. Major discoveries have included ConocoPhillips (Willow), Oil Search (Pikka-Horseshoe) and Pantheon Resources plc (Theta West). Willow, discovered by ConocoPhillips in 2016, has an estimated recoverable resource of 400 - 800 million bbls of oil. The Bureau of Land Management is currently working on a Supplementary Environmental Impact Statement and, if approved, Willow has an expected production rate of approximately 100 000 bpd. Oil Search announced a combined resource estimate for the Pikka-Horseshoe Units of 1.2 billion bbls of recoverable oil in 2017, with expected production around 120 000 bpd of oil. In April 2022, after winter testing, Pantheon Resources upgraded its recoverable resource estimate for Theta West by 48% to 1.78 billion bbls. Pantheon will commence further appraisal and testing in the 2023 winter drilling season. A unique characteristic of Pantheon’s portfolio, which includes Theta West, Talitha and Greater Alkaid, is its proximity to TAPS and the adjacent Dalton Highway with oil accumulations stretching directly beneath, giving Pantheon the ability to come onstream far more quickly. Pantheon intends to commence development of Greater Alkaid in the summer of 2022 with the initial drilling and longterm production testing of the Alkaid #2 horizontal well, spudded on 6 July. Pantheon will initially truck its oil the short distance up the Dalton Highway, and once relevant permissions have been granted, intends to ultimately ‘hot tap’ oil directly into the TAPS pipeline. Industry experts are hopeful that this resurgence of oil projects on the North Slope will lead to large quantities of

oil flowing through TAPS, improving the efficiency of the pipeline, at a time when it needs it most.

Permafrost Another area that has caused concern about TAPS is the threat of thawing permafrost. According to Inside Climate News, permafrost is found beneath nearly 85% of Alaska and is, therefore, below almost the entire pipeline. A study published in Nature Climate Change predicts that with every two degrees Fahrenheit increase, 1.5 million square miles of permafrost could be lost to thawing. This is a concern because it can undermine the structural integrity of the pipeline and ultimately increase the chance of an oil spill if supports holding up certain elevated sections get weakened.

Alyeska has worked to develop methods to futureproof the TAPS infrastructure to prevent these problems. For example, there are already about 124 000 thermosyphons along the path of the pipeline, which act to suck heat out of the permafrost and keep the ground frozen. The tubes are bored 15 - 70 ft deep in areas where warming might cause it to thaw. Michelle Egan, a spokesperson for Alyeska, claimed that changes to permafrost were considered in the original design of the pipeline, and so the pipe supports were designed and constructed accordingly to maintain the integrity of the pipeline. In this vein, out of the total 800 miles, 420 miles of the pipeline was built on elevated support systems which keeps the pipe about 6 ft off the ground. Many of these support systems have thermosyphons within the support systems to keep the permafrost frozen.

In 2021, it was reported that an area of permafrost where an 810 ft section of the pipeline is secured began to move as it thawed, causing some of the braces holding up the pipeline to twist and bend. The Alaska Department of Natural Resources approved the use of about 100 thermosyphons, which were to be free-standing and installed 40 - 60 ft in the ground to prevent the thawing slope from collapsing or sliding. Alyeska stated that the purpose of this was “to protect the integrity of the TransAlaska Pipeline from permafrost degradation”. According to records and interviews with officials, thermosyphons had never been used before in this way as a defensive safeguard. Tony Strupulis, Pipeline Coordinator for the Alaska Department of Natural Resources, said that the thawing of permafrost is a gradual process which allows time to address problems that it could cause, so there is no cause for alarm. Strupulis emphasised that the agency is “very mindful” of the permafrost in terms of the stability of the pipeline and that generally “the design philosophy is, if its frozen, keep it frozen”.

Keeping TAPS alive is imperative As demonstrated, TAPS is no doubt facing some substantial challenges, both in terms of the changing environment surrounding it through thawing permafrost and with historically low production and throughput rates. However, with the resurgence of exploration on the North Slope, as well as increasing political pressure to prioritise domestic energy production, there is every possibility that throughput rates should increase and the pipeline can thrive once again, at the same time supporting employment and providing valuable revenues to the State. Alaska has some of the largest oil reserves in the world, TAPS is underused and, given that the world is in an energy crisis and the US wants to regain its energy independence, the recent discoveries on the North Slope could act as a solution to a reliance on foreign energy. In addition, Alaska’s strategic location in the North Pacific would allow it to feed refineries along the US West Coast easier than the Gulf of Mexico would be able to. Given that TAPS, constructed with a 20 year lifespan in mind, just celebrated its 45 year anniversary, one can be confident that it is not going anywhere soon.

Figure 4. TAPS, Dalton Highway and Alkaid #2. (Source: Pantheon Resources plc)