15 minute read

Is the SBP taking minority shareholders of Security Papers for a ride?

The government, through the SBP is the majority shareholder in Security Papers Limited. But some other public shareholders suspect nepotism, incompetence and outright foul play. Profit places the single-buyer single-seller business of creating paper money in scrutiny

By Babar Nizami & Areeba Fatima

Advertisement

Nestlé Pakistan recently moved its head office by renting a space in Packages Mall. For those who are unaware, Packages Limited and its sponsors, the Syed Babar Ali family, also have a fairly substantial shareholding in Nestlé Pakistan. So much so that Syed Babar Ali and other members of his family are on the board of directors of both of these companies. So, when Nestlé rents a space from Packages, this can be considered problematic, as there is a clear conflict of interest.

Other shareholders of Nestlé Pakistan — the ones that have nothing to do with Packages or the Syed Babar Ali family — might feel that the management of Nestlé could be giving an undue favour to one of its substantial shareholders and directors, and the decision to move its head office might not be the most prudent one otherwise. They might even suspect that Nestlé might be paying above market rent, etc., to Packages to please a substantial shareholder (read Syes Babar Ali).

But before you, dear reader, start accusing Nestlé, Packages or Syed Babar Ali of foul play, let us clarify that such ‘related party’ transactions are not illegal, per se. However, there are some rules set by the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP) for such transactions. In its role as regulator, the Commission has created safeguards. The first safeguard is that these related transactions must be done at an ‘arm’s length’. In our example above, this means that common directors such as Syed Babar Ali should not be sitting in meetings held to negotiate such a rental arrangement. Instead, it should be independent directors who make these decisions. These are directors on a company’s board who are not employees of either company and should be asked to approve such arrangements.

But this alone is not enough. The SECP mandates companies to make comprehensive public disclosures regarding such transactions, giving out the details of the pricing mechanism and other terms in a transparent manner.

Even then, companies that believe in following good corporate governance try to keep such related party transactions to a bare minimum.

But what if there was a company that sold not just a small portion but almost all of its production to a related company? What if the product that this company made had only a single potential buyer that happened to be a related company — i.e., a company with substantial common ownership? And what if this company was the sole producer of this product and the related company also had no choice but to buy from this company? Unlike in our earlier example of Nestlé and Packages where it would not have made a big dent to Nestlé’s profitability even if it had hypothetically given Syed Babar Ali a favour and agreed to pay double the market rental rates, here, this one agreement — if reached unfairly — can be extremely beneficial for one company and extremely detrimental to the other. Obviously, the incentive to cheat will be much much higher here.

Will the safeguards put by the SECP still work? Or would the enormous incentive to cheat, ensure that such safeguards be brazenly flouted? Now imagine if this buyer was the government itself. Would the SECP be able to regulate its own or would this powerful buyer succeed in getting a favourably low price for itself? Would this not mean that other smaller shareholders in the seller company would lose out big time?

What we have described above is not just some hypothetical example. This is exactly the conundrum that minority shareholders of Security Papers Limited face today. In fact, in a recent letter written to the Chairman of the SECP, one such minority shareholder of Security Papers made several accusations about the lack of implementation of the related party safeguards mentioned earlier in our story. But before we delve into the concerns of this and other minority shareholders of Security Papers, let us first provide some necessary background.

Background

In the mid 1960’s the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) established Security Papers and listed it on the stock exchange. This meant that despite government control some of its shares were also sold to the general public.The company was given the task to manufacture the special paper required by the SBP to print its own currency.

Due to the sensitive nature of the product, the company to date, is the sole manufacturer of security paper in the country, most of which is naturally used in printing currency-notes. But this is not all. From ballot papers used in elections to stamp papers, passport booklet paper, and cheque book paper and the paper used to print college degrees, Security Papers makes it all. But since the main use of its security paper is in currency, its major buyer is a fully owned company of the SBP called Pakistan Security Printing Corporation, with more than 80% of Security Papers sales being made to Pakistan Security Printing. The most minimalist explanation of how this works is that Security Papers manufactures the paper on which Pakistan Security Printing prints the currency which SBP injects into the economy as part of its monetary and fiscal policies.

The fact that both of these companies effectively enjoy monopoly status, where a single buyer, and a single seller business of creating paper currency, already makes the dynamics between the two an interesting study. But what further complicates matters is the fact that Pakistan Security Printing (the buyer) also owns 40% shares of Security Papers (the seller) and thus is at least on paper in a position to influence the decisions of Security Papers. As already mentioned, shares of Security Paper are traded on the PSX regularly and more than two thousand individual shareholders own approximately 12% of the company. It is some of these minority shareholders that are always uncomfortable with the considerable influence of Pakistan Security Printing, a fully government owned entity, over their company.

Recent happenings and the pricing agreement

At the centre of this discomfort is the pricing arrangement between the two companies. Considering the peculiar situation of non-existent market forces, and the magnitude of the related party transactions, it was obvious that a special mechanism had to be created to decide the price that Security Papers would charge Pakistan Security Printing for its security paper. How this mechanism changed during the last sixty odd years is not relevant to our story. But what is relevant are the two relatively recent changes to this mechanism.

Nearly seven years ago, Security Papers reached out to Deloitte, an international accounting firm, to help configure a well-balanced pricing formula which would enable both Pakistan Security Printing and Security Papers to enter into a clear-cut and fair agreement on pricing. The disclosure in Security Papers’ financials mentions that all sales transactions with Pakistan Security Printing Corporation are carried out by the company using the cost plus mark-up method. Are there any more specifics mentioned in the disclosure regarding the Deloitte formula? We are afraid not.

However, Imran Qureshi, the current CEO of Security Papers, told Profit that the way it worked was that Deloitte would help Security Papers come up with a cost structure to charge Pakistan Security Printing. They suggested using a cost plus mark-up method, the modalities of which would be determined by the mutual consultation of the two boards. Very briefly put, the two boards would sit together in a tea-and-sandwiches meeting and decide the pricing formula between themselves.

Remember the two safeguards that the SECP had put to ensure that there is no foul play in related party transactions? The first was that these transactions are done at an arm's length and the other was that details of the agreement are publicly disclosed. From the explanation of the current CEO, it seems that both these safeguards were being flouted in the past. This is where the most recent change to the pricing mechanism comes in.

In 2022 Security Papers and Pakistan Security Printing decided to fix the issues with the old Deloitte pricing mechanism. Both Companies approached PWC (another international accounting firm) to come up with a new cost plus markup formula but one which was more objective and which did not require the two boards to sit together in a tea-and sandwiches meeting. The new pricing mechanism was put in place some six months ago (there is no clarity on the exact timeline), but it is apparent that even if it might have solved some of the problems with the last mechanism, minority shareholders of Security Papers feel they have been shortchanged. And they have solid reasons to believe that.

No arm’s length and dependent independent directors

This is the situation we now have. There are two companies in the equation: Security Papers and Pakistan Security Printing. One produces

Aftab Manzoor, Chairman Board of Directors, Security Papers Limited

paper used to print bank notes and passports and the other buys that paper and prints on it. The former is partially owned by the government, while the latter is fully owned by the government. But at the end of the day both are answerable to the federal government, and this becomes clearer when you zoom in on the shareholding of Security Papers.

The State Life Insurance Corporation (State Life) owns 8.48% shares and Pakistan Reinsurance Company Ltd owns 1.57% shares. Both of these companies’ administrative control is with the Ministry of Commerce. The Punjab Provincial Cooperative Bank, which is governed and managed by the Government of Punjab, owns 7.18% shares. And with the National Investment Trust (NIT) owning 5.67% shares, this brings the government's ownership of the company to almost 63%. Owing to this significant shareholding, the Govt of Pakistan effectively has majority on the board, making Security Papers it a state owned entity (SOE).

There is a vital question and legal definition that underscores this entire story. What is an independent director? According to the guidelines of corporate governance set out in the rulebook for Public Sector Companies, independent directors are non-executive directors who are not government servants. They also cannot be private individuals employed by a government institution.

Remember, this rule is specifically for companies in the public sector. And thus all of these rules apply to Security Papers. The composition of the company’s board, however, paints a rather blatant picture.

Take the example of Muhammad Sualeh Ahmad Faruqui, who is amongst the three independent directors of Security Papers. He is currently serving as Secretary Commerce, Government of Pakistan, However, despite this fact being true, he is on the board of Security Papers as an ‘independent’ director. How can a senior federal government employee in a majority government-owned entity be classified as independent?

The other two independent directors also face issues of neutrality or competence.

All this would make it seem that despite being an SOE, as classified by the SBP, Security Papers refuses to act like one and additionally stands in violation of the rules set for SOEs, whereby federal government employees are not allowed to hold the post of independent director on the board of this company.

This is not just a technicality. It is the Independent directors that are supposed to make sure and keep a check that nominee directors of major shareholders and the management of the company do not do anything that puts the minority shareholders, the ones that are not involved in the decision making of the company, at a disadvantage.

When Profit asked the CEO of Security Papers, Imran Qureshi, about the allegations against the board for not meeting the criteria of independence, he claimed that the company was in fact moving in a more positive direction, “You know our previous chairman Haroon Rasheed was the Managing Director at the Pakistan Security Printing from 2017 to 2021, during his time as Chairman Security Papers a Pakistan Security Printing employee was on board of both companies. There is no SBP or Pakistan Security Printing employee on our board now, in fact minority shareholders from Iran and Turkey are on the board. This company has an impressive minority representation – only 3 represent the major shareholders and six are from outside, out of the 9 shareholders.”

However, being a State Owned Entity, how independent can this board be when the biggest demographic represented on the board is ‘government employees’ or their nominees.

The good news is that a new SOE Governance law is in the final stages of implementation. The law intends to introduce some specific reforms. It establishes an SOE Board as an oversight body which is supposed to evaluate and monitor the compliance of SOEs. However, for this to work someone needs to make sure that Security Papers and its board knows that they are in fact an SOE.

No disclosures

Guess how we found out that the all important pricing mechanism was recently changed. There was no disclosure in any of the recent financial statements, nor was a notice of material information sent to the PSX and no press release issued either. We got to know about it, very casually, while interviewing company officials for this story.

When asked why the specifics of the pricing policy are not disclosed anywhere, especially to the minority shareholders and why have the profit margins of Security Papers plummeted all of a sudden Aftab Manzoor, Chairman of Security Papers Limited board of directors, said, “We don't need to disclose it, the margins will be clear to you in the end of year financials. Both companies’ management worked on it and presented it to the boards and they have approved it.”.

There is no way of telling from the quarterly or annual reports how this markup was exactly decided nor is there documented evidence of the shareholders having been informed of these decisions. The only way for them to tell that something has changed were the Profit and Loss statements which show that the profit margins have started to decrease dramatically.

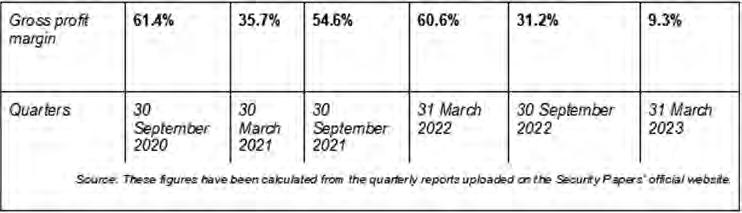

Both Aftab Manzoor and Imran Qureshi have confirmed that the newly revised formula was implemented within the last six months. This is a matter of significant concern considering that the company has maintained an average gross profit margin of 40% over the past 15 years. However, starting from the July to Sept quarter of 2022, the gross profit margin experienced a sudden decline. Looking at the latest quarterly report, the margin has plummeted to a worrisome 9.3%. This is at a time when inflation is at an all time high. The drastic fluctuation in gross profit margins caused by the formula's implementation demands a thorough and transparent clarification. Failing to do so would be negligent, especially when the impact is so pronounced.

Essentially, Imran Qureshi is claiming that the original transfer pricing methodology was flawed and the new system allows for adjustments in the final quarter. According to him, all the concerns of the minority shareholders will be addressed when the financial results for the company’s final quarter come out on the 9th of August. The only problem is that minority shareholders or the public at large were never notified of the specifics of the new formula.

Imran Qureshi told Profit that there are two parameters to this new formula: one is the cost, second is the markup which is now evaluated based on the weighted averages of companies listed on the PSX and of international security paper companies. “Earlier, these margins were a result of random mutual agreements between the boards but now there is a very clear justification and explanation; four international companies’ weighted averages of gross profit margins and the weighted average gross profit margin of the PSX listed companies.” But this information was never given to the shareholders directly.

Security Papers' earning per share (EPS), an important indicator of the financial health and performance of any publicly listed company, went down by Rs 8 on a year-on-year basis in 2022. One can accept the typical yet fair justification of such a drop; blaming the fledgling Pakistani economy and its effects on businesses, but with Security Papers, matters are quite different. Security Papers is in a very enviable position, any company's dream: zero competition. Therefore, if its costs were rising due to unfavorable domestic economic conditions such as rising inflation and currency depreciation, it could have simply passed that additional cost on to its guaranteed biggest customer, the Pakistan Security Printing. Instead, it has evidently absorbed most of that cost, increasing prices by a mere 1.7%. This sounds a little absurd.

If the Chairman laments in the annual report about local inflation and the rising rates of the global paper market because of international tensions, why did the company not explore raising the price?

“When our profit margins were consistently high, inflation was around 5-7 %, but in the past year inflation has been on the rise, so naturally this has led to an increment in cost but the end-of-year settlement has not happened yet so the true effect of the price adjustment as per the formula would only be noticed once our annual report is released on the 9th of August,” Qureshi explains.

The exact specifications of the markup and how it is determined have remained elusive in the quarterly and annual reports published by the company. The minimum risk free rate (price setting) that should reflect the rise in inflation and the subsequent rise in prices should at least accommodate the rate of inflation, and then some.

There is no way of telling from the quarterly or annual reports how this markup was exactly decided nor is there documented evidence of the shareholders having been informed of these decisions. The only way for them to tell that something has changed were the Profit and Loss statements which prove that the profit margins have started to decrease dramatically.

Also badly managed?

March 2023 and March 2022 comparisons show that the company’s earnings per share has been almost halved. More than Rs 2.5 billion were invested in bonds and mutual funds, the company has lost more than 38% to 40% of the principal in the last 6 years and did not make any returns while giving out huge sums in management fees. For a company with a Rs 6 billion market capitalisation, they have lost a lot of money in these bad investments. Aftab Manzoor justified this by saying “Once you look at the latest financials, you will see that we have gotten out of mutual funds totally. Because the idea was that we need to derisk our portfolio, there were some losses, we recovered those losses, it is now totally zero. We invested at market rates in the money market.” The June FY22 annual report shows that out of the total Rs 8.9 billion assets, Rs 3.3 billion have been invested in short term investments. The market capitalization reflects that the market values this company much less than its equity. Out of the total sales worth Rs 6 billion, 80% were made to the Pakistan Security Printing.

The minority shareholders note that considering this level of investment, the company could have earned bigger returns even if they just securely parked it in a savings account rather than making reckless investments which resulted in the company incurring losses. Considering that there are several bankers on the board, it should have been muscle memory for them to not invest in long term bonds (Pakistan Investment Bonds) as opposed to short-term maturity Pakistan Treasury Bills.

In the former type of investment, the interest rate is locked at a certain percentage for a period of 10 years but in the case of the latter kind of investment the tenor is much shorter, a maximum of one year in fact. A combination of investments in both money market products would have offered greater flexibility in taking full advantage of rising or falling interest rates.

For some very odd reasons, the board of directors at Security Papers invested in longterm bonds at a time when the interest rates were low, locking the investment at the same rate for a long period of time.

Solution to the problem

It is necessary to first understand the problem and then think of a solution.

Shareholders are concerned that they are being taken for a ride by a company that, for all intents and purposes, is owned majorly by the federal government. The financial results of the past three quarters do not inspire much confidence; the serious reductions in both the EPS and gross profit margin is a testament to the company’s deteriorating financial health.

Both Qureshi and Manzoor keep on insisting that the full annual accounts that will be released on the 9th of this month will settle all concerns and answer all questions. If that is indeed the case, then the shareholders would be proven wrong, all the hullabaloo and letters to the SECP would prove to be simply a simple case of unnecessary paranoia. However, even then one can not help but blame the lack of disclosures by Security Papers for all the confusion.

However, if the results fail to do this, then there is a very obvious solution to this recurring problem.

The government should simply buy back the 20% shares the public owns in Security Papers Limited and delist it from the PSX. This would take the public out of the equation and no one other than the government would be bothered about ‘pricing mechanisms’ and profits.

From manufacturing the paper for currency and other security printing, to the printing itself, everything would become a one window, singularly owned and run operation. n