23 minute read

Demonetisation — a solution to Pakistan’s woes or another disaster?

There have been proposals that demonetising Rs 5,000 notes will help combat tax evasion and black money. But what would such a move entail?

By Urooj Imran

Advertisement

Demonetisation is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it can tackle the problems of counterfeit currency, corruption, tax evasion, and inflation but on the other, it can harm the people who rely on cash for their daily transactions. It can shrink the circulation of black money, but it can also trigger cash shortages and chaos. It can speed up the transition to digital payments, but it can also leave out those who lack access to technology.

A government can decide to demonetise for various reasons, and it usually announces a deadline during which the currency — for example, Rs 5,000 notes — can be used or exchanged from banks. But demonetisation is not a magic bullet. It has many risks and challenges, and it requires flawless planning and execution.

It also depends on the context and conditions of each country. What works for one may not work for another. Demonetisation is not just a word — it is a process of removing the legal tender status of a currency, and it has been tried by several countries, such as India, the US, the EU, and Zimbabwe. But is it a good idea for Pakistan?

Why demonetise?

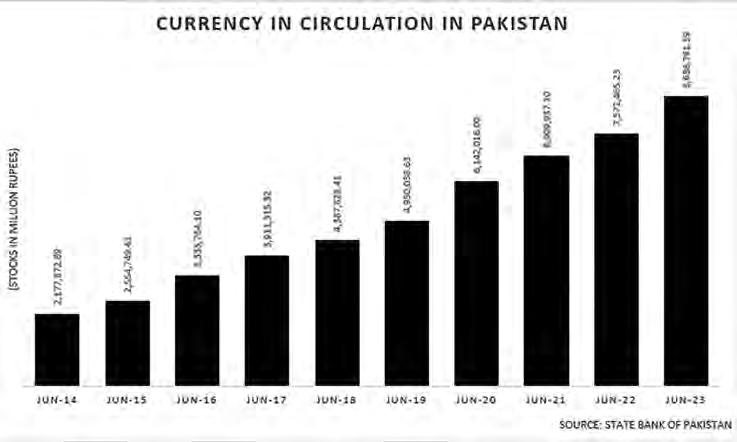

Independent macroeconomist Ammar H. Khan noted that there was a lot of cash circulating in Pakistan’s economy — Rs 8.68 trillion as of June 2023, according to the State Bank of Pakistan’s (SBP) latest statistical bulletin. He said that when this much cash was out in the open, it tended to find its way into sectors such as real estate.

“So, a lot of real estate projects are launched and informal businesses pop up because cash needs to find a way and it keeps getting reallocated towards these. It is not reallocated towards industry or other areas which can generate jobs,” he explained. “Proper allocation of capital is one reason to demonetise.”

Secondly, he added, higher currency in circulation also drives inflation, which rose to a record high of 37.97 percent in May. Khan elaborated that when cash is not being used for productive purposes, a country’s dependence on imports increases. So, eventually, the excessive cash in the economy drives more consumption and that consumption is supported by imports. Pakistan does not have the dollars to fund these imports, he pointed out.

And former Khyber Pakhtunkhwa finance minister Taimur Khan Jhagra said that in the context of creating barriers to the informal economy, demonetisation was “definitely worth considering”.

“In the context of bringing more of the grey and black economy [into the formal economy], we need to consider demonetisation as well as any other steps that will do the same. So, for example, encouraging transactions through credit cards, or other forms of e-payment etc., and incentivising those.”

A good idea or just more pain?

Asenior banking professional who spoke to Profit noted that Pakistan’s economic situation was bordering on “precarious” with foreign exchange reserves down to $ 4.46 billion as of June 30, 2023, inflation close to 30 percent, interest rate at a record high of 22 percent and many other factors that indicated a weak economy.

“Demonetisation is best done in stable economies, in which central bank reserves are adequate, inflation is low and GDP growth is decent to high — four percent. It will be regressive if it is done in this current environment when inflation is peaking [and] the economy is in the doldrums. Demonetisation at this point will only cause further nuisance for the general public. We are already burdened with inflation and high taxation, both direct and indirect.”

He added that the effects of demonetisation lasted for several months, which would be a terrible idea given Pakistan’s fragile economic situation.

However, Khan said that while the process of demonetisation would be complex and challenging, not going ahead with it would only mean prolonging the economic pain. “Might as well take the pain today instead of tomorrow,” he commented.

The banking professional also acknowledged that demonetisation could be a good idea for Pakistan under better economic conditions with certain prerequisites in place. One of the things that Pakistan would need prior to demonetisation was a proper digital banking infrastructure that would be able to sustain the exponential number of transactions that would result in the process, he said.

“The current infrastructure, unfortunately, is inadequate. It’s weak. When India went for demonetisation in 2016, it had the UPI digital banking system in place. So, it was able to sustain the impact of demonetisation and kind of smoothen the journey for the general public from cash to digital. So, from our perspective, I don’t think we are ready for it as of yet from the digital banking standpoint and also from the economic standpoint,” the banker said, noting that Pakistan kept going through boom-and-bust cycles — a process of economic expansion followed by contraction that occurs repeatedly.

Addressing this, Khan said demonetisation was actually a way to fix Pakistan’s boom-and-bust cycles. He elaborated that the country went through these cycles because it started consuming more, which in turn, required dollar-based imports. Demonetisation would help fix this as it would mop up the surplus cash in the economy and reduce consumption, Khan said.

However, it all depended on policy decisions, the economist continued. “When all this cash comes back into the system, how will the government reallocate it? Does it go towards imports or does it get reallocated towards a more productive area? So, demonetisation is the first step. Capital allocation is the second step that needs to be done.”

One effect of demonetisation is a rise in cash deposited in banks, potentially increasing the amount available to them to lend to businesses and spurring economic growth. The senior banking professional said, however, that in Pakistan’s case, the impact would be minimal.

“Let’s assume that of the currency in circulation (CIC) in Pakistan right now, Rs 3 trillion is in the form of Rs 5,000 banknotes, which are demonetised. This cash comes back into the banking system.

“However, Pakistan’s government is running a perennial deficit. Consequently, it is borrowing more and more. The incumbent government has borrowed Rs 3.5 trillion in the past 13-14 months, which is potentially more than the inflows [from demonetisation].”

If the government continued to borrow from commercial banks at a rate of Rs 500600 billion a month, then demonetisation, which would be a one-off measure, would have a “very temporary” effect, the banker said.

The effect on small businesses would also be zero in Pakistan’s case because its commercial banks traditionally do not lend to consumers or small and medium enterprises (SMEs) as they consider them to be “high risk”, he said.

“If demonetisation happens and money goes into the banks, the only beneficiaries are going to be those who were previously beneficiaries as well as large enterprises and conglomerates etc. So, SMEs, the agri sector, small businesses and individuals etc. will not see a positive impact because they will still not be lent money by the banks.”

What needs to come before

Economist Sakib Sherani, who has been part of economic advisory councils under different prime ministers, said that while demonetisation has its pros, people need to be careful about the idea as it could potentially cause a lot of disruption in developing economies.

Of the demonetisations that have happened around the world, very few have been successful, Sherani said. “The ones in developed countries have generally been more successful, but the ones in developing countries have been less successful and there’s a reason for that.”

This is because demonetisation could not be done in a vacuum, he explained. So, for instance, if the government withdrew Rs 5,000 notes from circulation, it would have to provide more notes of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 instead. Besides this, it would also need tax authorities and banks to have the proper infrastructure, instruments, and details of a framework to ask questions of people who brought in large amounts of that currency such as a sack full of Rs 5,000 notes.

“[The government] needs to have an entire protocol and a supporting infrastructure where it can ask these questions and then it also needs to close down all the other avenues. Pakistan has so many avenues for black money to exist,” he said, adding that the real estate sector among others needed to be taxed. Meanwhile, Khan said that one con of demonetisation would be the trouble people would face in depositing their cash in banks, but there were ways to mitigate this. A presidential order could be issued to mandate that anyone who had a CNIC would also need to have a bank account, he suggested. Everyone could be given a period in which they could deposit the cash, for example, three months, and the government could impose a tax on anyone who had undocumented cash beyond a certain limit.

Jhagra also said that demonetisation could be done in a phased manner. However, it should not take so long that people figured out a way to “game the system”, he added. The ex-minister said the government would need to evaluate which segment would be impacted most by demonetisation. “I think it would primarily still hit large cash transactions by a group that tries to stay out of the tax net.”

Demonetisation and taxation

Pakistan’s tax-to-GDP ratio — a figure to gauge tax revenue relative to the size of the economy as measured by the GDP — has remained between 8.4 to 9.8 percent over the last seven years — one of the lowest in the world. It was measured at 9.6 percent in FY23.

Can demonetisation reduce tax evasion? Khan said that once demonetisation happens, cash will come into the economy and evasion will “automatically reduce”.

“That’s the whole point. The surplus capital will come into the system and [the government] can tax it. If it does not want to tax it, that is a different story. Every single person in the world does not want to pay taxes. A structure needs to be in place in which people are forced to pay taxes.”

Therefore, demonetisation would need to be accompanied by Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) reforms, he added. This was what

Jhagra said as well.

“In this case, demonetisation is not a stand-alone initiative. It is part of an overall drive to get rid of or reduce the size of the informal economy. It would need to be accompanied by some [reform] drives at the FBR in terms of ensuring tax collection. It would be accompanied by bringing traders and large parts of the informal economy into the tax net,” he said.

“I would do demonetisation as part of a compendium of three or four major reforms so that it signals that we are actually breaking down the informal economy. In the current system, staying outside of the tax net and the formal economy is actually legal. You can choose to be a non-filer,” the former minister noted.

Meanwhile, Sherani spoke about the loopholes in Pakistan’s taxation laws. There is an entire section in the Income Tax Ordinance 2001 that allows people to bring in dollars to Pakistan without any questions asked, he pointed out. The economist was referring to ‘Part VII - Exemptions and Tax Concessions’ of the ordinance. Over the last 20-40 years, people have been converting money that originated from certain untaxed, unreported, or illegal activities in PKR and converting it into dollars, sending it abroad, and then bringing it back into the country using the loophole, he added.

“My whole point is that you just can’t do something without all the other important supporting instruments and frameworks,” he stressed.

He also emphasised the role of cashless transactions in widening the tax net as it would “close all other avenues [of evasion]”. While acknowledging that demonetisation would force people to deposit their Rs 5,000 notes in banks which would broaden the tax net, the senior banking professional said it would “once again have a one-time impact” because of the prevalent culture of tax evasion.

People would continue to look for ways to evade tax, he said, adding that this was why FBR reforms, strong tax machinery, and the right infrastructure were needed before initiating demonetisation, he added.

He pointed out that despite multiple International Monetary Fund (IMF) programmes, successive Pakistani governments chose not to tax the agricultural sector which makes up 30 percent of the country’s GDP. Taxes on real estate were low whereas taxes on the retail sector were either zero or non-existent, he added.

“A serious government would have already gone on to tax these sectors first. In my view, the government should be looking at the existing tax collection potential. If you look at the agricultural rent for land in Central Punjab, right now it is between Rs 150,000 and Rs 400,000 per acre. So, the agri rental income in Punjab and Sindh has gone up by four to six times. Whereas the tax paid on that land is zero.”

The India example

While several countries have demonetised currencies over the years, the most famous example is India. On November 8, 2016, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced in an unscheduled television address that the Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes — which accounted for 86 percent of the currency in circulation — were “just worthless piece[s] of paper” effective immediately. The public was told that it had until the end of the year to exchange the currency for new notes of Rs 500 and Rs 2,000, with the government framing the move as a measure to deal with corruption and black money.

This led to widespread chaos as long queues formed at banks across the country and a liquidity crisis was created. Sherani cited India as a cautionary tale and said it was a prime example of the disruption demonetisation could cause in developing economies. “It has been eight years and economists say the ripple effects are still being felt. Obviously, the government has [imposed] secrecy on how much damage was done but independent studies say that it ended with deep repercus- sions on small businesses and households.

“So, Pakistan needs to be careful. If we do decide to implement demonetisation, we have to plan it carefully, in a particular sequence, and it has to be done gradually.”

In a report written for Next Capital, former finance minister Hafiz Pasha noted that the percentage of currency in circulation in India as part of its gross national product declined rapidly post-demonetisation. However, it recovered strongly later, so much so, that the figure stood at 11.73 percent in FY21 compared to 7.7 percent in FY17 following the move to demonetise.

Separately, the senior banking professional also said that while demonetisation contributed to the increase in India’s digital transactions, COVID-19 had a greater impact. In FY21, India’s digital banking transactions were worth INR 5,554 crores, which was the first year of COVID. The transactions went up to INR 8,840 crores in FY22, and then INR 9,192 crores in FY23, according to data from India’s Press Information Bureau.

“So COVID, I think, had a greater impact on increasing digital banking and digital transactions as compared to demonetisation,” he commented.

Can a government do it?

Can a government, including a coalition such as the present one, actually push through demonetisation? Sherani believes the incumbent government or any other government with a similar sort of makeup and credentials would not demonetise “simply because they have very large constituencies that are in the untaxed or very lightly taxed sectors”.

“It is either agriculture or trade or the real estate sector. But these three sectors alone make up about 50-60 percent of the economy, so in that sense, it requires a government with political will, but also with a much more reformist makeup than the governments we have seen in Pakistan, especially this particular government.”

Meanwhile, when mentioned to Jhagra that economists appear to be divided on demonetisation, the former provincial minister commented, “Economists and lawyers are always divided on everything.”

He was also adamant that lawmakers stop thinking of political repercussions in terms of fixing the economy. “When you need to deal with a complex but critical issue, you are not going to wait to develop consensus, you are going to do your homework and implement. I think it is a fair assumption to say that if we (KP government) had not traversed the journey of pension reforms, the federal government would not have done it now.”

“And so similarly ... in terms of fixing the economy, the political cost cannot be questioned because those political compromises lead to plenty of political costs anyway. The current turbulence is linked to the fact that the economy is in bad shape. There has been a political cost to that anyway. The government is fearful of elections because they know that they are unpopular and they have shied away from many economic decisions. But if people are experiencing economic pain anyway, why not use that as a building platform and get through difficult reform?” he asked.

Pakistan has a very large and thriving shadow economy at present. According to a global research report of Ipsos on tax evasion published in 2022, its size is estimated at a whopping 40% of GDP. Demonetisation is one way to address this but clearly there are a lot of things that can go wrong if implemented in a country such as Pakistan where even more factors have to be just right in order to even think about such a major shake-up in the economy. Until the political and economic situation in the country is relatively stable, demonetisation may only remain an interesting idea to debate, not a serious policy proposal that is intended to be implemented fully by an elected government.

Nonetheless, there is a case to be made about its necessity in a system as stubborn as ours when it comes to reforms, that can address the problem of tax evasion and a general culture of nonchalance towards paying taxes and being part of the documented economy. n

By Abdullah Niazi

Only four men have held the office of both Chief Minister of the Punjab and Prime Minister of Pakistan. The first two managed this feat on technical grounds. The latest two, Mian Nawaz and Mian Shehbaz, are brothers.

The first to achieve this double was Feroz Khan Noone. An old Unionist stalwart who had served on Churchill’s war cabinet and whose split from Khizar Hayat Tiwana in 1946 proved vital to the creation of Pakistan, Noone was prime minister for just under 10 months in 1958 before his government was dismissed by Iskander Mirza’s martial law. But before his brief premiership, Mr Noon was chief minister of Punjab from 1953-55. But this was at a time when provincial elections and legislatures were not a developed concept, and Noone had been unilaterally appointed to the position by Khawaja Nazimuddin.

After Noone, the second person to go from Chief Minister of the Punjab to Prime Minister of Pakistan was Malik Meraj Khalid. An old favourite of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, Meraj was appointed CM after the 1971 general election for nearly two years before making way for Hanif Ramay.

Of course, Malik Meraj’s three months as prime minister were in a caretaker capacity. A venerable personality and a politician of immense integrity, Meraj was a man the nation often turned to at its darkest hours. During the ugly mud slinging of the vote of no confidence against Benazir, it was Meraj who steadied the ship with dignity as speaker. And when Benazir’s government was dismissed by Farooq Leghari, it was again Meraj who came in as caretaker and conducted a relatively fair election and remained aloof from Leghari’s efforts to politicise the process.

But the first man to not just hold the position of Chief Minister of the Punjab as well as Prime Minister of Pakistan but also be elected to both posts was none other than

Mian Muhammad Nawaz Sharif. With one stint as CM in the Zia era and three shots at the premiership, Mian Nawaz was alone in this achievement.

That is until last year, when his brother and loyal deputy took over as prime minister of the country. In an inverse, Mian Shehbaz has had three stints as chief minister and is in his first go as prime minister. With the recent announcement that the government will hand over control to a caretaker setup in August, the year long tenure of the younger Sharif has come to an end.

The only question is, how did he measure up and what will his legacy be?

The Shehbaz factor

There is a reason for doing this story. And while the little history lesson might serve as an interesting anecdote, it is also important for context. Ever since the independence of Bangladesh in1971, Punjab has been the single most electorally significant province in the country.

As a result it has had an undue amount of influence on the country’s economic and social development. The point is that while the Takht-e-Punjab has been one of the most coveted offices in the land (and perhaps the most powerful) there aren’t many politicians that have been able to be both strong chief ministers and strong prime ministers. In fact, it is only Mian Nawaz who retains a vague legacy for ‘good management’ in both capacities.

But when Shehbaz Sharif came into the office of prime minister, there were expectations of him. From 2008 to 2013 the younger Sharif had ruled the Punjab with an iron fist. As an administrator, Shehbaz was of a variety that can best be described as ‘basic but competent.’ These are the leaders and managers that rely on infrastructural development and tangible, marketable projects.

Remember, when Shehbaz came to power in Punjab, he was the first chief minister of the province after the 18th amendment. This meant that he was now also responsible for health, education, agriculture, taxation, and other segments of the economy and governance that have very direct implications on the voting population.

He quickly set out on a number of ambitious projects. Among his administration’s most prominent ventures were Lahore’s Metro Bus Project and the Orange Line Metro Train project — both of which are highly subscribed and have made a significant impact on Lahore’s public transport. But the effort was not entirely concentrated on this as it should be. Shehbaz’s government also was quite happy to build roads, widen boulevards, make corridors signal free and construct underpasses and flyovers.

There were other successes. The handling of waves of dengue fever in Punjab were thwarted and later governments in other provinces like KP learned later that this kind of management was not easy. Multiple sources, both bureaucrats and politicians that worked closely with the younger Sharif in these 10 years, have said that another major feature of his government was efficiency.

“As CM he obviously was not managing the economy. But he was still involved in economic management,” says one former departmental secretary who served under both Shehbaz Sharif governments. “I still remember meetings about prices in Ramzan Bazaars would happen months before Ramzan. The CM was also deeply interested in waste management and bringing in Turkish companies to help manage this issue as well. He worked tirelessly and abhorred inefficiency.”

While Nawaz was often seen as the one who could pull in crowds and win over voters, Shehbaz became known more for his practical skills in implementing policy and for his ambitious development agenda in Punjab.

“I worked for seven years with Shehbaz Sharif and became a key member of his team to reform and digitise the Punjab government. From disease outbreaks to attendance of school teachers; from land records to government taxes; from disaster management to metro buses,” says Umar Saif, former chairman of the PITB. “Everything was run by state-of-theart digital systems, generating real time data and analytics for informed decision making. Shehbaz Sharif knows governance better than anyone I have met. His ability to learn new things alway impresses me. Keeping up with his speed and expectation is not easy.”

This was a reputation that Shehbaz earned over the years. He was supposed to be an effective administrator that “got the job done” with his quickness being dubbed ‘Punjab Speed’. Of course on many other fronts he failed. Punjab’s educational outcomes continued to remain low, and in fact from 2008-2018 the share of students going to private school in the province rose from 28% to 38% on the elementary level. Healthcare facilities also saw no significant improvement but none of this stopped Shehbaz from developing the reputation of a hard nosed, dedicated, administrator.

How being CM is different from being PM

In 2018 things changed. The Pakistan Tehreek i Insaaf came to power in the centre and despite being the single largest party in the Punjab Assembly could not form a government. The era of Usman Buzdar began and with his elder brother in exile, it fell to Mian Shehbaz to take up the mantle of leader of the opposition at the centre.

In many ways this was a demotion. The Chief Minister of Punjab is a powerful man. On some days even more powerful than the prime minister. Yet it was still a step into federal level politics. And for Shehbaz it was also an opportunity. It is worth mentioning that Shehbaz has had national aspirations for a while. Back in 2013 when the PML-N came into power in Islamabad, Shehbaz had contested a national assembly seat. “Mian Shehbaz very seriously considered giving up the chief ministership to come to Islamabad and take over the energy ministry. The 2008-13 PPP government had some successes but failed at fixing the load shedding problem,” says one

Umar Saif, former chairman of PITB

party insider. “Mian Sb thought he would take over the power ministry and solve this high profile issue.”

Of course, there was another angle to this. The younger Sharif was also hoping to give a boost to his son Hamza’s political career by installing him as chief minister and also setting him up to eventually succeed his uncle Mian Nawaz as the leader of the party. Eventually the Sharif family patriarch decided that Hamza was too young and Shehbaz’s talents would be better spent on Punjab. But in 2018 there was no option for him but to dutifully take up the role of opposition leader.

This is a journey many politicians all over the world have made. Where a provincial or state level leader rises up and becomes a national leader. In neighbouring India, the best example is Prime Minister Narinder Modi who was an illustrious chief minister in Gujarat for many years before he became PM. Much like Mian Shehbaz, Modi gained a reputation as a no nonsense CM that got things done. Other Indian PMs including P.V Narasimha Rao had also made the journey from CM to PM.

In the US, it is an even more common phenomenon. Of the 80 Americans who have served as President, Vice President or both since the nation was formed, 27 or just over one-third had been governor of a state. This includes 17 of the 45 presidents (38%) and 16 of the 49 vice presidents (33%).

But not everyone can take the heat of the transition. Largely the problem is that managing a country on a federal level and managing a province are two very different ball games. There are some similarities such as parliamentary work and cabinets, but largely these are very different jobs. Essentially, a prime minister is only really responsible for three things: defence, diplomacy, and the economy. A chief minister has a lot more to do.

Remember, ever since the 18th amendment the federal government has a lot less on its plate. But since devolution has not gone down to local government levels, a chief minister is still able to do projects such as road building and other such initiatives. But that doesn’t mean a PM has nothing to do with development.

Essentially, there are three ways a PM can work on infrastructural development. There is the building of national motorways and highways which are essential for travel but also for trade. Then there is electricity generation which is also a huge hurdle. These are both arenas in which Mian Nawaz excelled during his multiple stints as PM. And then finally there are national subsidies and packages targeting different groups of people or sectors of the economy.

So how has Shebaz Sharif fared on these fronts?

The role of PM and how Shehbaz measured up

To put it mildly, it has been underwhelming at best. When the PDM coalition ousted Imran Khan and brought Shehbaz Sharif in, the headline that the UK’s Guardian ran with was “Shehbaz Sharif: the diligent administrator now PM of Pakistan.” The expectation was that the younger Sharif would bring his famous ‘Punjab Speed’ to Islamabad. “While Khan was known for charisma, Sharif’s reputation is one of capability,” said Fahd Husain, a senior journalist and later SAPM to Mian Shehbaz, when he was first elected. Hussain said Sharif’s leadership style would probably mark the end of the “confrontational” and populist politics Khan came to be known for, where he made grand promises of reform and held large rallies, and he would instead be a prime minister who “talks less and works more”.

“Shehbaz is used to rolling up his sleeves and getting down into the nitty-gritty of work. We will be seeing a workaholic in office who will obsess on issues of performance, governance and delivery.”

How did that go? Look at it this way. In his time as CM, Shehbaz used to insist on being called “Khadim e Ala” instead of “Wazir e Ala”. The title actually caught on. When he became prime minister Shehbaz dubbed himself “Khadim e Pakistan” in an attempt to graduate from Punjab politics. Let’s just say that title hasn’t quite stuck.

The task Mian Shehbaz walked into was gargantuan. The country was hurtling towards default after a deal with the IMF was completely derailed by the previous government, difficult decisions had to be made, and no government that was coming in could find itself in a situation where the electorate would be happy with them.

This seemed to be enough to paralyse Punjab Speed. Mian Shehbaz ended up dragging his feet on the issue of removing the fuel subsidy that former prime minister Imran Khan had put in place and this resulted in negotiations with the IMF souring. While he had to let go and hike petrol prices eventually, decision making remained sluggish.

Eventually, the biggest fumble from Mian Shehbaz has been the appointment of Ishaq Dar as finance minister in place of Miftah Ismail. With his brash style, Dar delayed the IMF programme significantly. In the eight month period where the IMF would not sign a staff level accord, Mian Shehbaz’s own credibility took great hits because of the constant repetitions that the deal was right around the corner.

Eventually, to his credit, it was Mian Shehbaz himself who managed to secure the deal. In the last week leading up to the end of June, the prime minister met with the director of the IMF on the sidelines of an international moot, the government bulldozed an amended budget through parliament, the State Bank of Pakistan convened an emergency meeting of its Monetary Policy Committee, and the IMF released a statement expressing it satisfactions with the steps taken by Islamabad. It became painfully clear that the PM had to step in himself and do the job Dar was unable to do.

“From the 22nd of May to the 23rd of June the government walked over coals to get the deal and avoid default. Through various missteps, tantrums and shifting goal posts one thing has remained constant: sustained clarity of PM Shehbaz. He deserves most credit for the deal,” said Fahd Hussain in a tweet following the deal being secured.

It is true that Mian Shehbaz has a certain diplomatic charm that some like. He is fluent in multiple languages and his mannerisms and ease in speaking to other world leaders helped him in what was a significant success for Pakistan at the COP27 conference of the UN which was vital to the country after a year of catastrophic floods.

However, the fact of the matter is that when he came to power the most significant issue was securing a deal with the IMF. He has succeeded in doing so. On other fronts, his Prime Minister Youth Initiative and other such programmes in the recent budget will gain him some popular support. But as far as development is concerned, he did not have the time to do so. His mandate was for a year and in that year the job on his plate was avoiding default and safely moving towards elections. He has managed both, but not with the efficiency he has come to be known for. This brief stint as PM will be a blow to his otherwise good reputation as an administrator. Whether he gets another shot at rectifying this is for the electorate and his older brother to decide. n