22 minute read

Track-and-Trace troubles

Track and trace is one way to counter our tax collection problem. But it only scratches the surface

By Abdullah Niazi and Shahzad Paracha

Advertisement

It was a strange sight watching a ranking officer of the Federal Board for Revenue (FBR) receive applause as he took the dais at an event organised by the Society for the Protection of the Rights of the Child (SPARC). What does an Additional Director of the FBR’s Track and Trace Project have to do with advocating for children’s rights?

The answer might surprise you: Big Tobacco. The 1st of June is marked as the international day for ‘No Tobacco’. The event organised by SPARC was meant to raise awareness regarding the dangers passive smoking poses to the health of children. Mr Sarfaraz was present at the event because of a recent achievement by the FBR — they have managed to increase the amount of tax they collect from tobacco producers.

The revenue board claims that behind this success is a ‘Track-and-Trace’ or ‘T&T’ system that they have been in the process of implementing since late 2021. And it isn’t just tobacco. As part of Pakistan’s commitments to the IMF, T&T systems have been introduced in the cement, fertiliser, and sugar industries as well in addition to tobacco. In fact, sources within the FBR have told Profit that by their estimation they can collect around Rs 200 billion tax by implementing T&T in five sectors including petroleum, tea, pharmaceutical, tyres and spices.

And the success in the tobacco industry would indicate that the track-and-trace methodology works. Tax revenue collection from the tobacco industry has increased 13% from the first ten months of the current fiscal year following the implementation of the Track and Trace System. That amounts to an impressive Rs 17 billion in additional revenue.

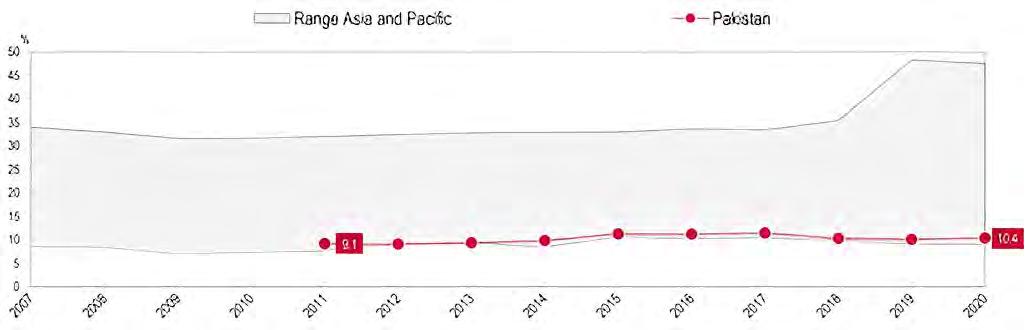

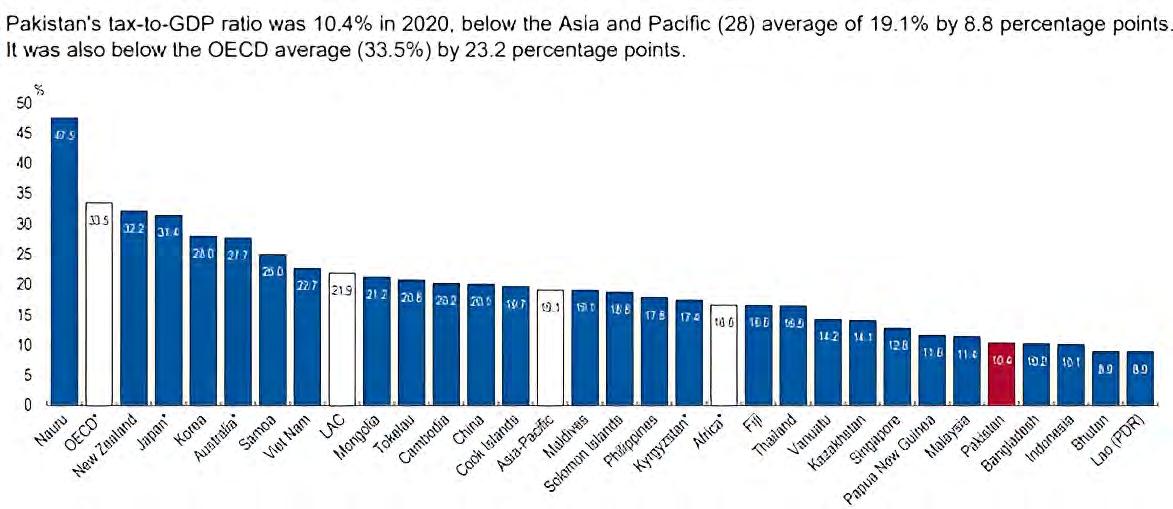

You see, Pakistan has a taxation problem and it is worse than you think. A recent report of the World Bank placed Pakistan at an abysmal number 173 in an international ranking of paying taxes. Pakistan’s tax to GDP ratio, which is the ratio of the tax revenue of a country compared to its GDP and tells how well the government controls a country’s economic resources, has been in single digits for years. In comparison, the highest tax-toGDP ratio in the world stands at nearly 50%. Even by regional standards, Pakistan is nearly 10% behind the 19% average in the Asia-Pacific region.

Pakistan lags behind both in tax collection and in increasing our tax net. At the same time the government’s expenditures increase every year. So what happens in the budget whenever Islamabad needs more money? You squeeze the already small base of taxpayers even more. That is the easy solution. Bringing people into the fold of taxation is never easy. That is why the government chooses workarounds like high GST rates and income tax that can be deducted from anyone and everyone across the board. Implementing a progressive taxation system would require documenting and running after large businesses and taxing their incomes and profits. This would both provide relief to the existing taxpayers and the general public and also increase the government’s revenue.

But is T&T the way to go about this? In the past year, as part of its attempts to meet the conditions of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the government has tried to implement a track-and-trace (T&T) system in at least four different industries: cement, sugar, fertiliser, and tobacco.

These are all industries and products that are susceptible to the black market. With a T&T system, the government would be able to keep a closer eye on how much these industries are producing and tax them accordingly. Other than in the tobacco industry it has proven to be glitchy and has had the different industries it has been introduced in up in arms.

On top of this, Pakistan’s taxation issues go far beyond just a monitoring problem. The federal government is the only real collector of taxes and most of those funds are distributed through the NFC awards to the provinces. Tax collection on a provincial level is low and completely non-existent on a local government level — where it should be the highest and most robust. So how has the T&T system done in Pakistan? How have the industries mentioned reacted to the increased watchfulness of the FBR? And how far could this measure really go?

The track-and-trace system

Manufacturers often under-report their production numbers precisely to evade tax. This is where the problem starts. Say, for example, that you are a fertiliser manufacturer and produce 500 bags of Urea. The demand for fertiliser from your plant is 400 bags. Now, if there are 500 bags being produced that would mean the supply is increasing beyond demand which results in the price falling. The problem for the manufacturer is that the government will tax every single bag of Urea that is purchased. So instead of reporting these extra 100 bags, the producer will show that they are making an even 400 bags and sell the remaining 100 at a lower price free of tax.

{Editor’s note: Urea has just been used as an example here and the production numbers are also simply hypothetical and meant to help the reader understand better.} This then creates an artificial shortage. In most industries under reporting is much more blatant than in our example. Urea, cigarettes, cement, and sugar are susceptible to artificial shortages and are also part of smuggling rackets. Just last month the FBR’s customs department (yes the FBR has one of those precisely for this reason) seized urea fertiliser and sugar worth Rs 392 million from Baloch- istan’s Khuzdar during three raids as part of a major anti-smuggling operation. Customs Intelligence seized 41,883 bags of urea having a market value of Rs 167.53 million, and 44,957 bags of sugar having a market value of Rs 224.79 million.

It’s a pretty simple system. Manufacturers underreport their production numbers. They then sell the unreported surplus production outside of the tax net at cheaper rates and the black market grows. This has resulted in startling estimates of just how big the shadow economy is in Pakistan with academics and researchers estimating the size of this undocumented economy anywhere between 40-80% of the country’s GDP.

So what can be done about this?

The T&T system proposes that tax collection be done directly at the source. That means the government monitors production and catalogue how much a company’s output is and then tax them directly on those numbers. So if we go back to our fertiliser example, when the government first brought in a T&T system it asked the fertiliser industry to invest heavily in a mechanism that would have a stamp placed on each and every bag of fertiliser produced which could then be scanned before it was sold. The data from this scanning would go directly to the FBR which would then record the total number of bags produced and tax them accordingly.

T&T solutions are used across the globe to assist in the process of tax collection. But how have these four industries in particular reacted to the attempts, and has the track and trace system had any results that speak to its efficacy?

Unpopular and ineffective?

Technology enhanced tax collection solutions offer the most feasible, reliable and trustworthy approaches to taxation. With minimum human intervention a T&T solution, if implemented in a proper and transparent manner, can safeguard the interests of tax revenue collection by providing traceability and process visibility through automated data capturing at all relevant role players in the respective supply chains and enabling tax collection governance based on real-time information. It can also act as a deterrent to tax fraud entailing visibility of production volumes and product attributes and dis-incentivising fraudulent activities such as under-declaration; and ensuring a level playing field.

In principle the concept makes sense, but the reality is a little more complicated and the response from the industries has been lukewarm. The T&T system had originally been the idea of the IMF. They had suggested a Track and Trace system in October 2021 for the tobacco, cement, sugar and fertiliser industries with a view to enhancing tax revenue, reducing counterfeiting and preventing the smuggling of illicit goods through the implementation of a robust, nationwide, electronic monitoring system of production volumes.

Essentially, the system would fix more than 5 billion stamps on various products at the production stage which was meant to enable the FBR to track goods throughout the supply chain. Essentially, industries would stamp their products right after packaging them and then scan each one before selling it so that the data for production volumes goes directly to the FBR.

Going forward with the fertiliser example, in November last year the fertiliser sector banded together to complain about problems with the stamp system. In a letter to Federal Finance Minister Ishaq Dar and Chairman FBR Asim Ahmad, fertiliser manufacturers of Pakistan Advisory Council (FMPAC) claimed that the technology being used by the FBR (which the board had strongly armed the industry into investing in) did not work. They claimed, for example, that less than half of the stamps actually scanned even though the scanning efficiency was supposed to be 99%.

Now there could be two explanations for this. The first would be that the FBR did indeed bring in a flawed system which does not work. Later reports found that the board had not conducted a feasibility study to see if the stamps would work in Pakistan. The other explanation of course is that the industry was also unhappy with their production being tracked so closely and very quickly decided to shift the blame onto the system that the FBR brought in.

Implementing a T&T system requires a lot. FBR in its directions clearly stated that the tax stamp needs to be applied on the surface of the product in a location that is most accessible based upon the presentation of the bags to the applicator. On the other hand, manufacturers need to provide high speed internet connectivity so that once a stamp is scanned the data goes directly to the board. This then also requires a suitable location for the installation of equipment, an isolated power terminal point of 220v 15 Amp and floor space for the Unique Identifying Mark applicator that is used to put the stamps on.

The tobacco counterpoint

Largely, different industries have complained about the efficiency of the T&T system and feel that they have been made to invest in something that does not work. To counter this, the FBR points towards the example of the tobacco industry where the track-and-trace system seems to have resulted in an increase in taxation revenue. As we mentioned in the beginning, there is some proof that indicates T&T has been successful at least as far as tobacco is concerned.

The board managed to collect Rs 149.40 billion in sales tax as well as Federal Excise Duty (FED) from the tobacco sector from July 2022 to May 2023. In comparison, the tax department had only collected Rs 132 billion in tax revenue from July 2021 to May 2022. In the last five years, the revenue collection from the tobacco industry has increased from Rs 116 billion to Rs 149 billion.

And this is despite the fact that the tobacco industry has been producing fewer cigarettes.

There has been a 17% decline in cigarettes produced and sold during July to April this year. The tobacco sector produced 46.83 billion sticks in 2022 which has now decreased to 36.40 billion sticks. Similarly, the sale was 42.70 billion which also declined to 35.48 billion sticks.

But wait a second, if production fell then why did the tax revenue increase? And on top of that, wasn’t the entire purpose of the T&T system to beat under reporting? The answer to this question lies in a unique feature of the tobacco industry which has also made track and trace so widely used and successful when it comes to tobacco.

There are two MNCs that operate in Pakistan. One is the Pakistan Tobacco Company Limited (PAKL), which is the Pakistani subsidiary of British American Tobacco. The other company is Philip Morris Pakistan Ltd (PMPK). Together, these two companies control more than 90% of the documented tobacco industry in Pakistan. Their biggest competition, however, comes from local companies that under report their numbers and account for around 10% of the tobacco market.

According to estimations made by the MNCs, while they have 90% of the documented market share, they only have around 65% of the overall market share. That is because local cigarette manufacturers under-report their numbers, avoid being taxed, and sell cheaper cigarettes. PTC and PM together are the two largest tobacco producers in the country and have 65% of the market share. Other than them, there are 52 companies that produce and sell around 35% of the cigarettes in the country. However, these 52 companies only pay 2% of the total tax revenue collected from the tobacco industry annually.

The smaller companies sell cigarettes in the shadow economy free of tax and are able to undercut PTC and PM. This naturally irks the MNCs which then regularly lobby and push for the smaller manufacturers to be taxed more. The MNCs actually lobby for higher taxes that are more stringently imposed on the local growers and manufacturers. They believe that because they pay so much more tax while local producers do not, they have an unfair advantage that allows them to control 35% of the market share.

Let us not be under any illusions here. Large tobacco companies are not making these demands out of any sense of duty or goodwill. No, they want more people to smoke more cigarettes and given the chance, they would splurge on advertising, marketing, and packaging the product. And after completely dominating they would then lobby for lower taxes.

But the results have been there for all to see. The FBR’s Track and Trace system has kept illicit trade from going above 15%. There have also been other uses of the Track and Trace system. Three local tobacco companies, namely Paramount Tobacco Company, Millat

Tobacco, and Tobacco World, have signed the Tripartite Agreement (TPA), thus integrating themselves into the Track and Trace System. The big tobacco facilities that account for 97-98 percent of the tax revenue generated by the sector will experience advantages from the inclusion of local tobacco companies in the system. Additionally, improved enforcement measures can effectively suppress the illegal trade of non-duty paid tobacco products, thereby assisting legal product manufacturers in meeting their revenue targets.

The real taxation problem

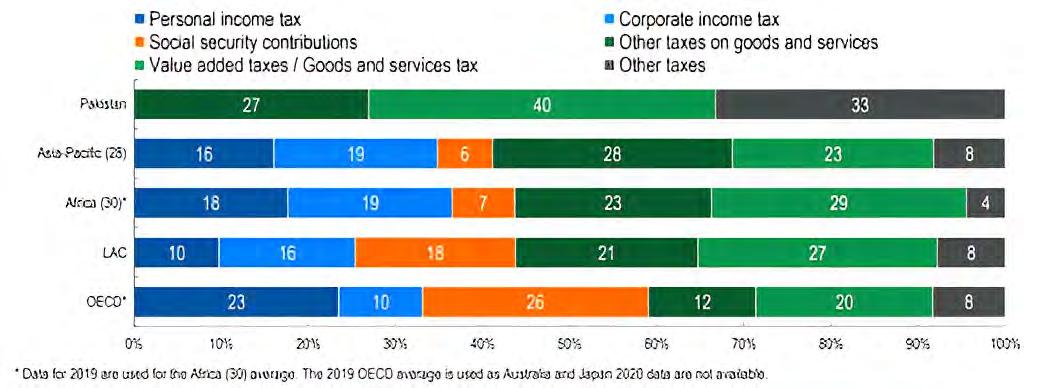

Of course, this is all a question of methodology. The real problem is that Pakistanis are taxed unfairly and those that should be paying the lion’s share end up paying nothing. Just take a look at Pakistan’s tax structure. Tax structure refers to the share of each tax in total tax revenues. The highest share of tax revenues in Pakistan in 2020 was derived from value added taxes / goods and services tax (39.8%). The second-highest share of tax revenues in 2020 was derived from other taxes (33.3%).

In comparison to Pakistan, countries in the Asia-Pacific region only collect about 23% of their taxation from goods and services taxes — meaning Pakistan’s average is almost double. Why is this the case? The biggest reason of course is that taxation in the country is centralised. The FBR collects almost all taxes (even the ones that should be collected by provinces under the 18th amendment) and then those collections are then given to the provinces in the form of the NFC award leaving the federal government with very little spending money. “The problem is how the NFC award is structured, the percentage that goes to the provinces needs to be reduced. Around 60% of what the centre collects goes

We as a country have failed to implement the beautiful 18th amendment. The implementation has been slow and weak. Despite having access to the two biggest cash cows, services and agriculture, the share of provincial tax revenue is close to 1% of the GDP. You would be surprised to know that the corresponding number for Indian provinces is around 6% of the GDP, with similar fiscal powers

Dr Hafeez Pasha, former finance minister

to the provinces,” says former finance minister Miftah Ismail.

Former Finance Minister Dr. Hafiz Pasha, while talking to Profit, lamented that, “We as a country have failed to implement the beautiful 18th amendment. The implementation has been slow and weak.”

Since the share of the provincial governments, under the NFC awards, over the last few years has been increased from 40% to around 57%, it has provided the provinces with very little incentive to develop their own revenue sources. Despite having access to the two biggest cash cows, services and agriculture, the share of provincial tax revenue is close to 1% of the GDP. “You would be surprised to know that the corresponding number for Indian provinces is around 6% of the GDP, with similar fiscal powers,” says Dr. Pasha.

The solution of course is right in front of us: devolution. More than just being a third tier of democracy, having a local bodies system means having a new economic process. In essence, it is not just a new administrative stratification, but also involves the dispensation and spending of money. Things such as education and health that people automatically look towards the provincial government for would now be handled by local representatives. Perhaps most crucially, the ability of local governments to collect taxes and release their own schedule of taxation allows them to make their own money and spend it on themselves rather than waiting for the benevolence of the provincial or federal government.

Of course, devolution to local governments is still a long way away. In the meantime, the Track and Trace system needs to be better implemented with proper feasibility studies before tech is brought into the country. Otherwise this will be another in a long list of failures where the state will be unable to improve our tax collection mechanisms and widen the cast its net. n

By Daniyal Ahmad

Envision this: you’re yearning for a sleek new phone, but unlike the rest of the world, you can’t just snag it on a monthly plan. No, you and I are forced to confront the grim reality of coughing up the full price upfront or settling for a dinosaur. It’s hard to shake off the nagging feeling that something’s amiss. Why are we being denied the same privileges as others?

The bitter truth is that our industry is caught in a paradoxical situation that echoes the notorious Prisoner’s Dilemma in game theory. This ageless enigma illustrates how rational choices can lead to catastrophic outcomes. It involves two prisoners, isolated and unable to communicate. They’re faced with a choice — cooperate or betray. Cooperation reaps the greatest reward, but betrayal is often chosen. Here’s the twist — acting in their own self-interests doesn’t produce the best outcome.

It’s the ultimate example of how communication, rather than isolation, can lead to mutual benefits. This dilemma has confounded economists and philosophers for years. It’s arduous to find a direct manifestation of this, but Profit might have just found one. And it may just explain why we can’t get a phone on a contract like our friends overseas.

Setting the stage — have phones become more expensive?

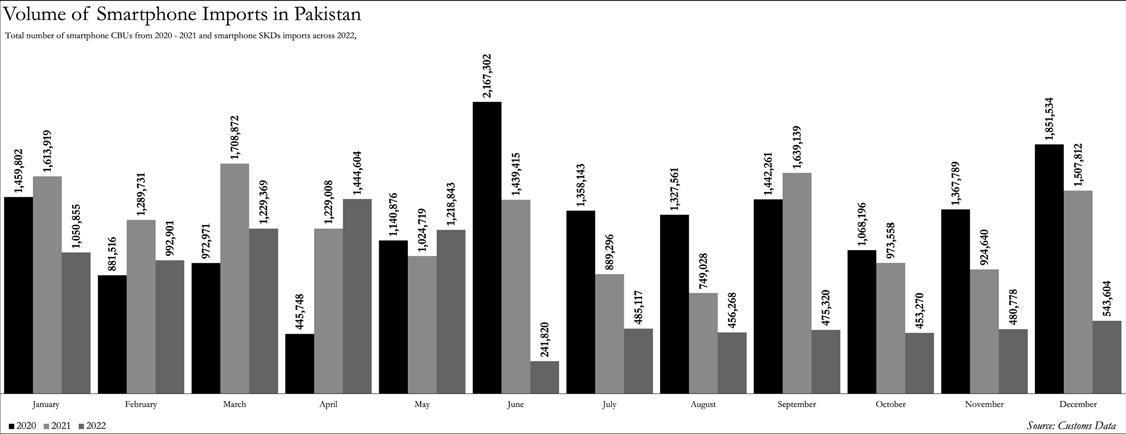

Have mobile phones become more costly? “With over 100 phone models that change every four to five months, obtaining such information is challenging,” states Aamir Allawala, CEO of Tecno Pack Telecom. “Nonetheless, I can confirm that prices have risen due to the Rupee’s depreciation. The local value addition is 15%, with the rest of the phone dependent on imported components,” adds Allawala. Profit, thus, examined Pakistan Customs’ data for insights.

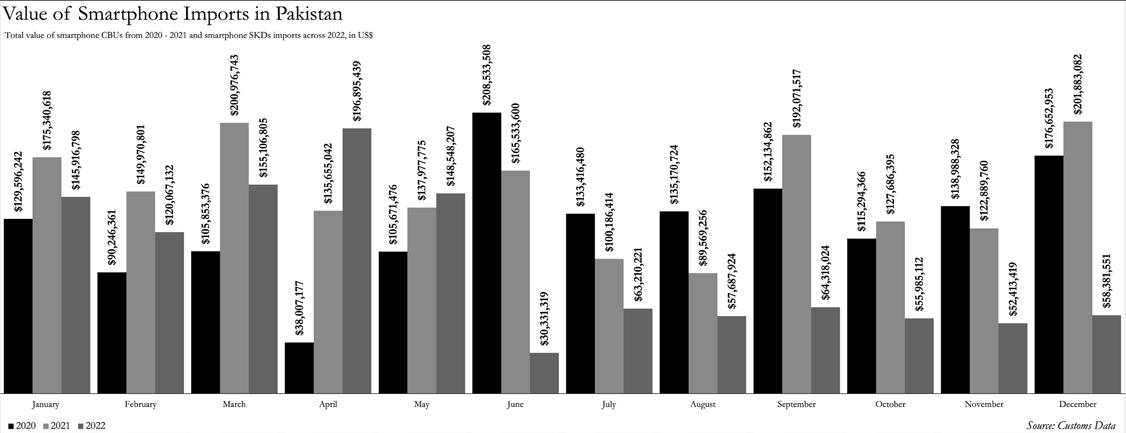

In 2020, Pakistan imported $1.52 billion worth of completely built-up (CBU) smartphones, increasing to $1.79 billion in 2021. CBU data for 2022 was unavailable, but Pakistan imported $1.14 billion worth of semi-knocked down (SKD) kits in 2022. CBU refers to the final handset while SKD refers to individual mobile components assembled to create a phone.

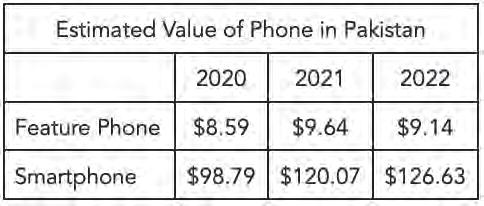

In terms of volume, Pakistan imported 15,483,699 smartphone CBUs in 2020 and 14,989,137 units in 2021. The volume for SKD units was 9,072,749. Subsequently, dividing the value by the volume determines a phone’s average price.

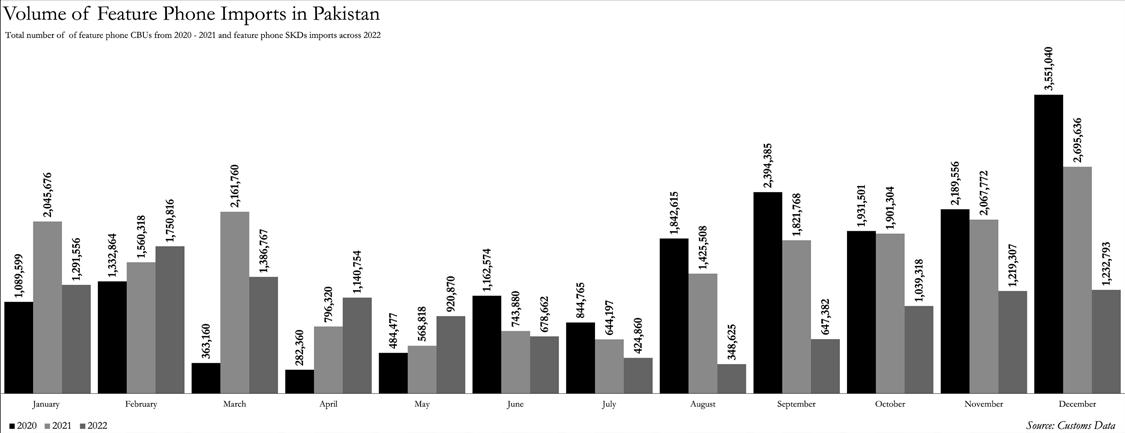

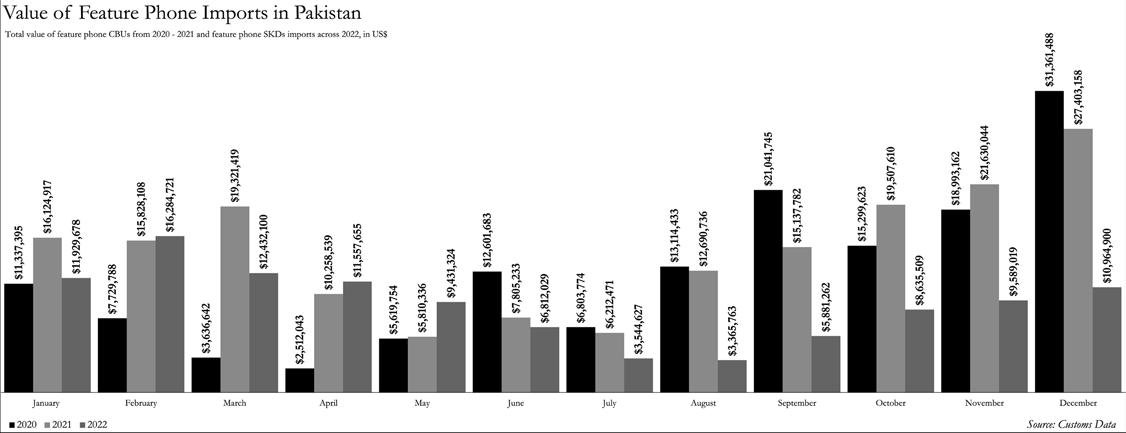

In 2020, Pakistan imported $150,515,530 worth of CBU feature phones, rising to $177,730,353 in 2021. The value of SKD units was $110,428,587 in 2022. The volume of imports was 17,468,896 units, 18,432,957 units and 12,081,710 units respectively.

The average smartphone price subsequently rose from $98.79 in 2020 to $126.63 in 2022. Similarly, the average feature phone’s price increased from $8.59 to $9.14. However, this is a rudimentary metric. This is unrepresentative of customer experiences that Profit encountered when engaging in conversation for this piece. The average value of feature phones declined in 2022 from 2021, whilst the increase in the value of smartphones does not seem as pronounced as our conversations alluded to. There are simple explanations for this. with the trend observed from 2020 to 2021. Thus, phones have become costlier due to factors beyond the Rupee’s depreciation — the use of SKD kits. What’s up with the kits then?

Why they might stay expensive for a while to come

The rising cost of living in 2022 may have led to importing more affordable phones altogether. Another reason for the dip between 2021 and 2022 is the existence of SKD units instead of CBUs. SKD units require assembly and are devoid of final taxes and profit margins. It is reasonable to assume the actual price trend aligns

The Government launched the MDMP in 2020 to stimulate domestic phone production. It levied duties on imported phones to foster local manufacturing. The policy resembles our automotive policies, where manufacturers achieving economies of scale enhance cost and features for the user. This accounts for the prevalence of SKDs over CBUs, and the rising and persistent cost of CBUs. Profit has previously explored this in depth for those interested.

Read more: Pakistan’s cellphone industry: A prospective $15 billion exporter or another automotive-style catastrophe

So, where do we stand? Our phones have become costlier. Companies producing them must attain economies of scale for customers to benefit from quality and price improvements, but those remain elusive. How do we persuade people to exceed their purchasing power? Instalment plans seem obvious. However, we’ve reached the core of our story. Why do we lack these contracts? This is where we enter the labyrinthine mess known as the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Let’s begin with phone manufacturers.

What’s the phone manufacturers’ point of view?

“iPhones dot the European and American markets, but not every customer paid Rs 500,000 like us. Globally, telecom operators are the buyers for phones. They buy them in bulk and sell them to customers in easy instalments,” elucidates Allawala. Why don’t ours then?

“Phone loans are unsecured loans. Financing for phones exists for credit card customers, using their cards as collateral,” explains Muhammad Naqi, CEO of Premier Code. In fact, most don’t. According to Karandaaz, only 1.9 million credit cards existed across Pakistan in December 2022.

“Across the developed world the risk is borne by a bank or telecom operator, and not the brand,” expounds Naqi. “Unless the operator gets involved, obstacles will persist. There’s always a chicken and egg problem for a brand. If a brand has decent cash sales volume, why give a year’s worth of credit?” Naqi adds further. “Let’s assume a telecom operator wants 100,000 devices on credit for a year. If I take the

Muhammad Naqi, CEO of Premier Code

exposure of Rs 300 million for a year and the delinquency rate is 30%, that’s Rs 90 million lost. Manufacturers don’t operate on high enough margins to bear such costs,” laments Naqi. However, isn’t this just a case of underwriting then? Surely, the banks could do it. No?

Do banks care?

“Our banking system eschews documentation, recovery efforts, and insurance acquisition,” laments Allawala. How cogent is his claim?

“Banks finance handsets directly through credit card guarantees or personal loans,” states Shahzad Ishaq, Group Head of Digital Banking & Chief Digital Officer at MCB. “But that’s disparate from signing up for a service contract as it operates abroad. The bankable population is 18% of the eligible adult population. This constrains what we can do, but we can do something for that 18%,” Shahzad adds.

“If the bank were a partner, the contracts would be underwritten. Underwriting involves checking the repayment ability, debt burden, bureau checks, past records, and more. With a good underwriting process, you can reasonably foresee that the customer will pay,” explains Shahzad.

“Looking at operational costs for a loan worth Rs 40,000-60,000, it’s feasible because there are decent margins around what we call a personal finance arrangement or a loan originated in a pre-underwritten product. The average credit line on credit cards is close to Rs 80,00090,000. That suffices to cover people for a Rs 50,000 handset which can be purchased, and put on an instalment plan. Similarly, personal finance can be initiated,” Shahzad elaborates.

As with all ventures, banks must assess the opportunity cost. “This uncharted territory can be juxtaposed with the existing abundant opportunities. With the current market discount rate at 21%, such an exorbitant loan becomes perilous,” warns Shahzad.

“Given the climate, both telecom companies and banks deem this an unscalable venture due to the lack of social impetus. It is purely a commercial endeavour. While it may warrant experimentation, its scalability is dubious,” Shahzad reflects. Despite his optimism, Shahzad’s hopes are put to question by MCB and its counterparts’ inaction. What’s up?

A head of consumer banking at another bank consented to expound on the matter anonymously. “Financing is a means to an end,” they stated. “Abroad, telecom operators lead the consumer-facing aspect of cellular financing. They undertake all marketing, and visibility efforts. While there is a financing angle, the onus of devising and maintaining a financing solution rests on the telecom operator,” our source elaborated.

So where are we? In limbo. Manufacturers bemoan the lack of support while banks shun undue risk in a sector where they perceive the market maker to be another entity. However, both parties singled out telecom companies in their criticism. Are they culpable?

The telecom operator question

“Our country operates on a prepaid market model. Most consumers eschew long-term relationships with operators,” laments Khurrum Ashfaque, Chief Operating Officer at Telenor.”In contrast, the global postpaid or contract market necessitates customers to sign up for 1-2 years. This establishes a long-term commitment with their telecommunications provider. This arrangement affords the provider the opportunity to offer bundled handsets as part of the contract, with payments spread out in instalments.” Ashfaque explains.

“Our core business provides data and connectivity services and does not entail lending or loans for handset purchases,” Ashfaque clarifies. “The average revenue per user (ARPU) for a telecommunications subscriber within the local industry is less than $1. This demographic diverges significantly from the typical clientele of banks. The checks and balances required to assess creditworthiness incur exorbitant costs, rendering it an unappealing model with high credit risk. Banks shun such territory,” Ashfaque elaborates.

“Even if we could surmount financial hurdles, technical complications pose further challenges. For instance, in other markets, telecommunications providers do not permit customers to switch to competitors while bound by a contract.,” Ashfaque continues.

“Enforcing such technical control here is unfeasible due to the prevalence of ‘jailbreak’ technologies. Handsets procured through loans can be effortlessly unlocked in the open market,” Ashfaque adds.

Allawala builds on Ashfaque’s points. “Even if we could brick the phone, what’s to stop individuals from storing it in a drawer or using it as a paperweight? They could even disassemble it and sell the parts,” he elucidates.

Putting the pieces of the puzzle together

With all parties having had their say, it’s time to pit them against one another. They’ve evidently yet to convene for this conversation.

First and foremost, let’s address the ingenious methods customers may employ to breach their contracts and abscond. “By thoroughly vetting a customer’s creditworthiness through underwriting and credit screening, the odds of them going rogue are significantly reduced,” Shahzad asserts. Let’s double down on mitigating this risk.

“In the absence of traditional financing solutions, some companies have begun collateralising the phone itself to sidestep the issue,” Naqi exclaims. “Samsung has its own solution, as does my brand. Google plans to roll out a device locking component on all its phones in 2024, which the company will enforce,” Naqi adds. “Google’s locking feature across Android phones will open up new financing options,” Allawala chimes in. Let’s get everyone onboard now.

“Any entity seeking to enter the mobile phone financing arena may collaborate with telecommunications providers. Our contribution to this ecosystem comprises an extensive network of franchises and retailers throughout the country, as well as a comprehensive analytical database of consumer behaviour, usage, and demographics that can facilitate the identification of suitable users for smartphone purchases.,” Ashfaque elaborates.

Surely, by combining the solutions proposed by all three parties, the risk can be ef- fectively mitigated. Easier said than done, you might say — but Profit would like to believe they possess the acumen to distinguish between a genuine customer and a rogue element if they put their heads together.

Now we turn our attention to part two: Scale. Whilst banks and manufacturers have already broached the subject of scale, what about telecom companies? “The true benefits will materialise with mass market adoption and attaining a scale of millions for such handsets. Participation in this journey will only be meaningful if it achieves mass-market scale. Entities seeking to collaborate with telecommunications providers should envision mass-market scale rather than niche value propositions.,” Ashfaq expounds.

We have already delved into the intricacies of financing and recovery. So what sort of scale are we tentatively envisaging? According to Karandaaz’s financial inclusion survey as of February 2023, a mere 19% of the total adult population possesses a bank account. However, there’s room for expansion.

We have already explored the intricacies of financing and recovery. So what sort of scale are we tentatively envisaging? According to Karandaaz’s financial inclusion survey as of February 2023, a mere 19% of the total adult population possesses a bank account. However, there’s room for expansion.

“An average of 35 million phones are sold in Pakistan annually. Assuming only half of them are smartphones and we can only tap into 30% of that half, that still leaves us with a staggering 5 million potential customers for whoever is willing to tackle this challenge head-on,” Allawala declares.

With all that done, is Profit forcing this relationship onto the requisite sectors? Or is there actual interest amongst our sources to actually see this through?

A case of the jitters?

“With prices soaring, it is only a matter of time before this becomes a reality. It hinges on priorities and the ability of banks and other financial institutions to launch a program of this nature,” Naqi exclaims. “People will naturally transition from feature phones to smartphones. I firmly believe that, apart from the most orthodox individuals, everyone desires a smartphone. If someone is willing to finance this transition, it could be expedited; otherwise, it will unfold at its own pace,” Allawala adds.

“It is entirely feasible. Manufacturers, banks, and telecom companies must engage in a delicate dance for this to work,” Shahzad states. “I think we are too risk-averse in this market, so there is a tendency to stick with tried-and-true methods. It simply needs to be tested,” Shahzad muses.

“Each party must shoulder the risk associated with their area of expertise. As a telecom provider, our strengths lie in distribution, our network, the services we provide on top of that. The risk associated with loan schemes, and device inventory should be assumed by the parties best equipped to mitigate it,” Ashfaque elucidates.

“The time is ripe for this idea. However, each party must play their respective roles to ensure a sticky relationship triangle,” Shahzad exclaims.

“Banks will engage in underwriting by assessing debt burden, ability to repay, and existing bureau records. The telco will safeguard the relationship through a service or custodial service contract. The manufacturer can provide analytics on the mobile customer base or assist in upgrading programs by tapping into their existing customer bases,” Shahzad continues.

Now Profit does not provide matchmaking services, so all the aforementioned players will have to get together on their own initiative. However, they might not even require Profit’s assistance because this is far from a forced union. Clearly, all of them seem keen to play ball. There’s theoretically money on the table to be made. It’s just a matter of who is going to take the first step, and dimension it. n